Last Friday and Saturday, Sidney Crosby took the Stanley Cup to his hometown of Cole Harbour, Nova Scotia. It was a busy 24 hours in the Halifax area, as Crosby brought the Cup to a local Tim Hortons (being the most famous graduate of the Timbits hockey program), took it to his local hockey school for children and brought it to a Veterans hospital on the Friday. On Saturday, he paraded with the Cup in Cole Harbour.

Screen shot taken from the Internet feed of Crosby’s Cole Harbour parade.

Crosby did many of the same things during his 24 hours with the Stanley Cup after Pittsburgh’s victory in 2009. Didn’t seem like anyone was tired of it, though!

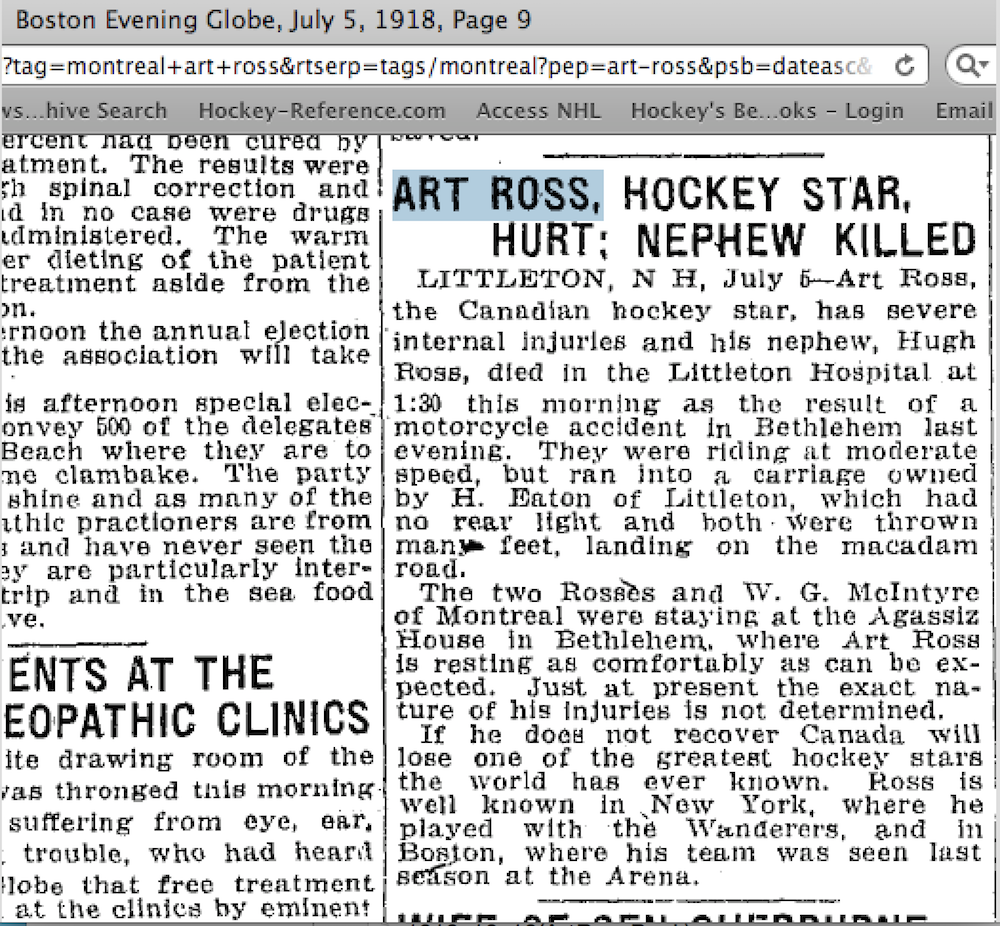

After Sidney Crosby’s time in Cole Harbour, the Stanley Cup was flown to Madison, Wisconsin, where Phil Kessel and his family spent some time with it in their hometown on Sunday. On Monday, Kessel brought the Stanley Cup to Toronto. People hadn’t seemed thrilled with the idea when the controversial ex-Leaf said he was thinking about a Toronto visit after Pittsburgh’s victory. Even so, Kessel seems to have won the hearts of his detractors with his unannounced visit to share the Cup with the young patients at the Hospital for Sick Children … a Toronto institution he had quietly supported throughout his time with the Maple Leafs.

Screen shots taken from Sick Kids video of Phil Kessel’s visit.

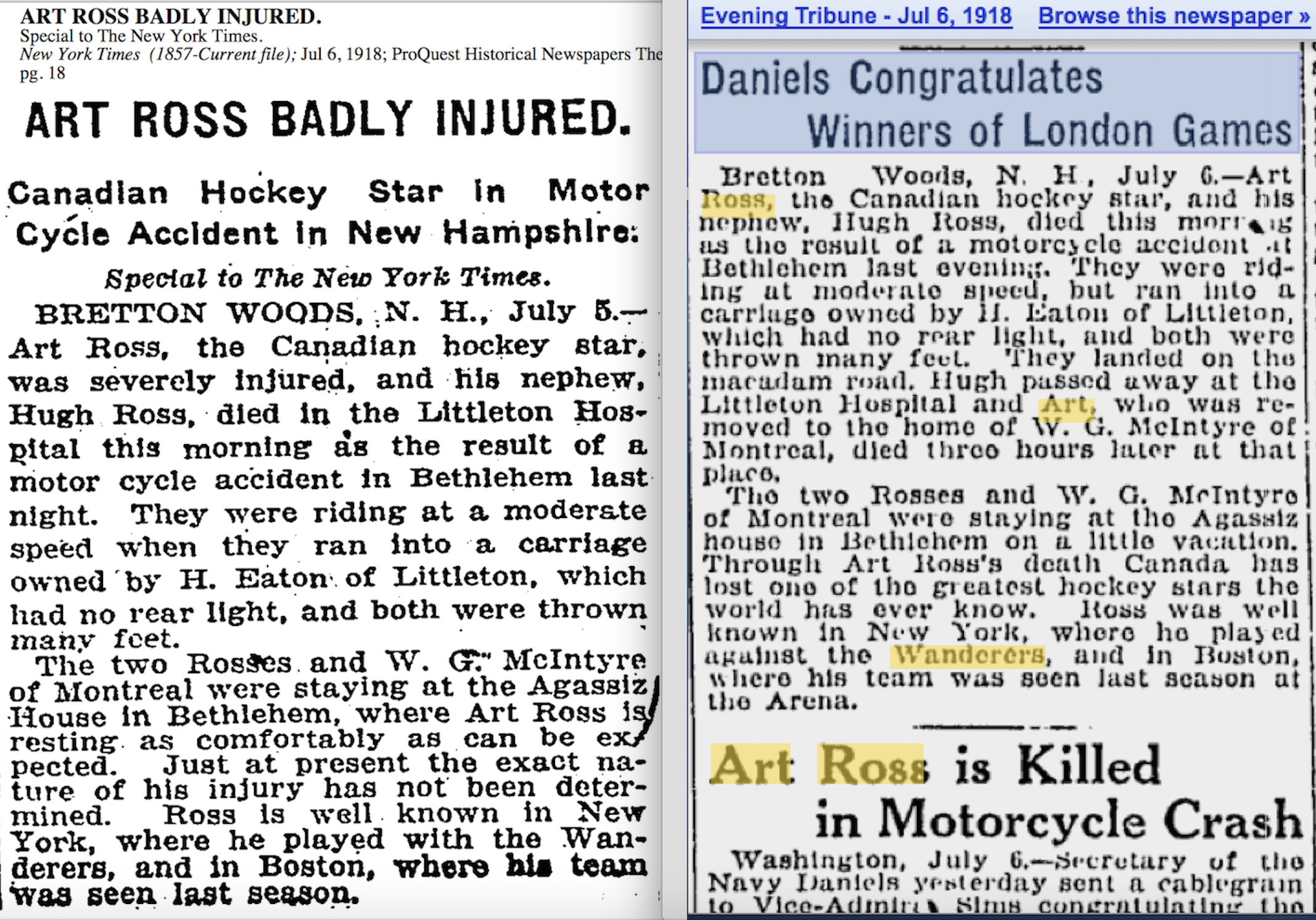

Phil Kessel isn’t the first former Toronto star to bring the Stanley Cup to town after winning it with another team. The very first time the Cup visited Toronto was way back in February of 1901. It came in the care of George Carruthers. Never heard of him? Well, you likely would have if you were a hockey fan in Toronto in the late 1890s. He played with the Toronto Rowing Club and the team from Osgoode Hall, and Toronto newspapers circa 1899 referred to him as the best cover point (defenseman) in the city.

In the fall of 1900, work took Carruthers to Winnipeg. He caught on as a spare player with the Winnipeg Victorias, perennial champions of Manitoba, and was with the team when they defeated the Montreal Shamrocks in a tight series that wrapped up on January 31, 1901. On their way back to Winnipeg with the Stanley Cup, the Victorias stopped off in Toronto to make a pilgrimage to the gravesite of their former teammate Frank Higginbotham, who had died in his hometown of Bowmanville, Ontario, shortly after the Vics’ first Cup win in 1896.

Clippings from the Toronto Star and The Globe, February 5, 1901.

Photo of George Carruthers is from the Society for International Hockey Research.

George Carruthers was “The Keeper of the Cup” during its visit to Toronto, and on February 5, 1901, he put Lord Stanley’s prize on display for the citizens of his hometown in the show window of J.E. Ellis, a jeweller with a store on the corner of King Street and Yonge – less than a five-minute walk from the current location of the Hockey Hall of Fame. The clip from the Toronto Star says of Carruthers and the Cup, “when it is not on public exhibition, he carries it around in the pocket of his coon-skin coat.” The Stanley Cup was a lot smaller in those days, but even so that must have been some big coat Carruthers was wearing!