On this night 115 years ago (a Friday in 1907), a proud home town celebrated the Stanley Cup victory of the Kenora Thistles at the Hilliard Opera House. Kenora had won the Cup a few weeks before, with victories against the Montreal Wanderers on January 17 and January 21, 1907, to sweep their best-of-three series. Hopefully, around the time this year’s Stanley Cup playoffs start in late April, you’ll finally be able to read all about it in my new book, Engraved in History: The Story of the Stanley Cup champion Kenora Thistles published by Rick Brignall of Rat Portage Press.

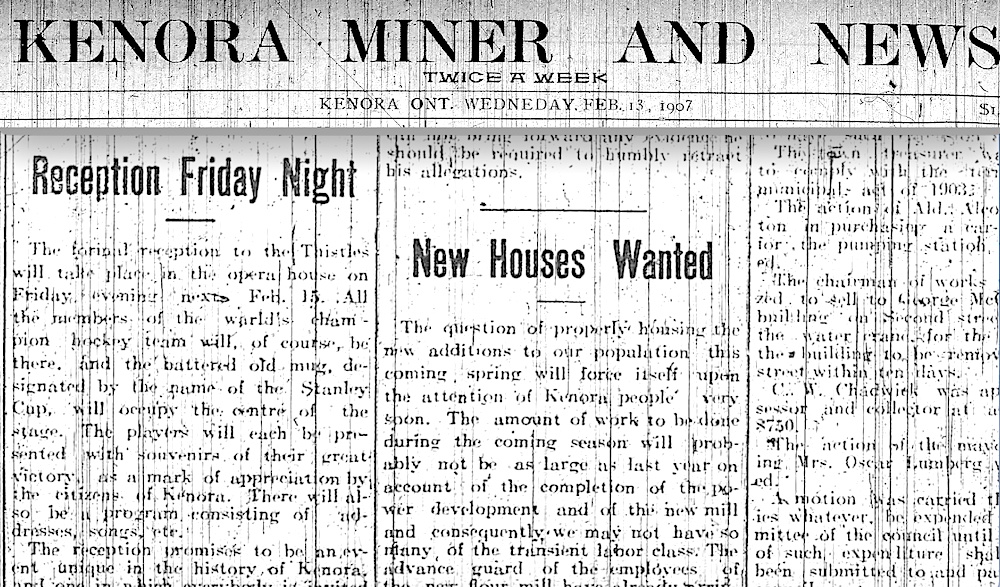

As to that party 115 years ago tonight, “The reception promises to be an event unique in the history of Kenora,” said the local newspaper, the Miner and News, two days before, “and one in which everybody is invited to take part.” The night would be “a bright, joyful, enthusing occasion,” and “you will have regrets if you don’t attend.”

For people who wished to be there, “an admission fee of 50 cents will be charged the gentlemen.” This was in order to defray the costs of the civic celebration. “The ladies will be admitted free.” There were also tickets available to sit up in the gallery at 25 cents apiece. No account is given as to how many people actually attended, but a recap of the evening in Saturday’s paper describes an “immense audience.” It would certainly appear that a fine time was had by all.

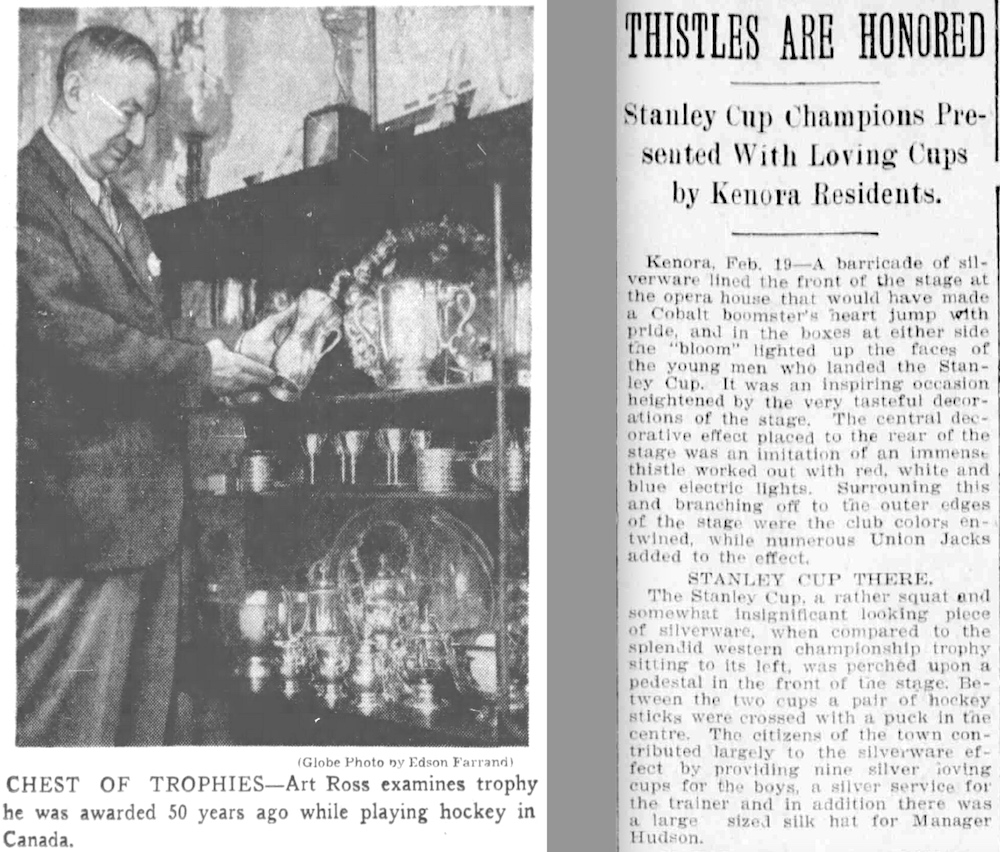

The auditorium in the Opera House was decorated with flags and bunting, and there was “an imitation of an immense thistle, worked out with red, white, and blue electric lights.” The colour scheme matched the numerous Union Jacks surrounding the Stanley Cup, which was perched upon a pedestal at the front of the stage. It was described as, “a rather squat and somewhat insignificant looking piece of silverware when compared to the splendid championship trophy [the Stirling Cup of the Manitoba Hockey League] sitting to its left.” At the time, the Stanley Cup was only a little bit larger than the bowl (now a replica – the original is on permanent display at the Hockey Hall of Fame) that sits atop the trophy today.

The evening began with opening remarks from Mayor Charles Belyea, who also read letters of regret from Art Ross and Joe Hall. (The two players who had been borrowed from Brandon were now back in that Manitoba town and playing against Portage la Prairie that same night.) Next up were a few musical numbers, before team executive Dr. Nelson Schnarr addressed the crowd.

Schnarr’s “humour sallies” were “well approved by the audience.” In this new age of openly professional hockey players, he jokingly remarked that it was due to the ladies of Kenora that the town had the best team in the game. After all, efforts had been made from time to time by other clubs to lure away Kenora’s stars, but they had chosen to remain loyal to the team because “affection and sympathy will hold a man when dollars will not.”

known as the Hilliard House (a combination hotel/theater) on the same site.

After concluding his remarks, Schnarr relinquished the stage for several more songs and speeches. Another team executive, John McGillivray, was among the others speakers, and he gave a short history of the team’s attempts to win the Stanley Cup since 1903. “Nothing succeeds like perseverance combined with ability,” he said, “and the Thistles had both.” He concluded his remarks by saying: “We have made a record in going after the Cup oftener than any other team. Let us make another record by defending the Cup oftener than any other team.”

Next, came the hit of the evening. Evelyn Gunne, poet, singer, and wife of local doctor William James Gunne, sang a song she had composed specially for the occasion. Mrs. Gunne had written and performed a similar song at a reception for the team in 1905 after the Stanley Cup loss to Ottawa that year, but now she re-worked the words to celebrate the victory:

We sing of the might of Britain, boys,

In the face of Britain’s foes,

And side by side, on the veldt, boys,

We’ve fought for the English Rose,

We own a sneaking fondness, boys,

For the Shamrock, green and bright,

But the bravest blooms of all, boys,

Are the Thistles, we cheer, tonight.

The Union Jack, and the colors, boys,

Are the things for which we fight,

But the colors that hold our hearts always,

Are those of the Red and white.

We bid you welcome home, boys,

The news from sea to sea,

Is only heard in praise, boys,

And joy of victory.

We’re proud of you at home, boys,

And of your well-earned fame.

We’re proud of your bumps and bruises,

Because you have played the game.

The Thistles are the winners, boys,

From Halifax to Nome;

They’re hailed as kings of hockey, boys,

Our Thistles here at home.

We love to hear you praised, boys,

We value what they mean,

When every message tells us,

“Kenora men play clean.”

It’s words like these we prize, boys,

The words we least could spare,

’Twas great to win the Cup, boys,

But best you have won it fair.

The Thistles are at home again,

Our bravest and our best.

We are not perhaps the biggest town,

But the proudest in the west.

Phillips and Griffis and Ross, boys,

McGimsie and little Giroux,

Hooper and Beaudro played, boys,

As often we’ve seen them do.

The East has sadly laid, boys,

Her hard won laurels down,

Before the whirlwind victors,

From our little lakeside town.

Three times you’ve tried to win, boys,

“Three times and out,” they say,

But now the Cup is ours, boys,

For you’ve brought it home to stay.

After that show-stopper, former mayor A.S Horswill had the honour of presenting silver loving cups to the players, nine of which had been commissioned by the citizens of Kenora for presentation. (Art Ross and Joe Hall received their commemorative trophies later. Today, the Hockey Hall of Fame has both, along with the cup presented to Billy McGimsie.) There was also as a silver tea service for the team’s trainer, Jim Link, and a large silk hat for manager Fred Hudson. Tommy Phillips, the captain, stepped forward to receive the trophies on behalf of his teammates, and made a short address to the crowd:

On behalf of the club and the players, I would like to thank the citizen of Kenora for the splendid reception you have tendered us. It gives us pleasure to know that we have been fighting for a good cause and for a good bunch of people. We have tried, every time, to do our best as we felt we had the reputation of the town at stake. Now that we have the Cup, I hope the team that takes it from us will have as much trouble as the Thistles had in winning it.

Phillips also thanked the officers of the club for their support over the years, and then the evening concluded with a final song before everyone stood to sing “God Save the King.” Those in the audience remained standing to offer “hearty and ringing cheers” to “the world’s champions.” The players responded with three cheers themselves for the people of Kenora.

After the celebration, the Stanley Cup was displayed for the whole town to see in the window of Johnson’s Pharmacy, the Main Street drug store owned and operated by Thistles president Joseph Johnson and his brother Lowry. But by the time the Cup arrived in town, it was already becoming clear that the team’s defence of the prized trophy was going to be difficult.

For more, you’ll have to wait a little longer … and buy the book!

But, if you’re looking for a little hockey & writing talk right now (or at least, on Thursday!), please join by Zoom at 7 pm on February 17 for conversation and Q & A with me and Paul White courtesy of the Owen Sound library.

No registration necessary. Just click here on Thursday at 7: