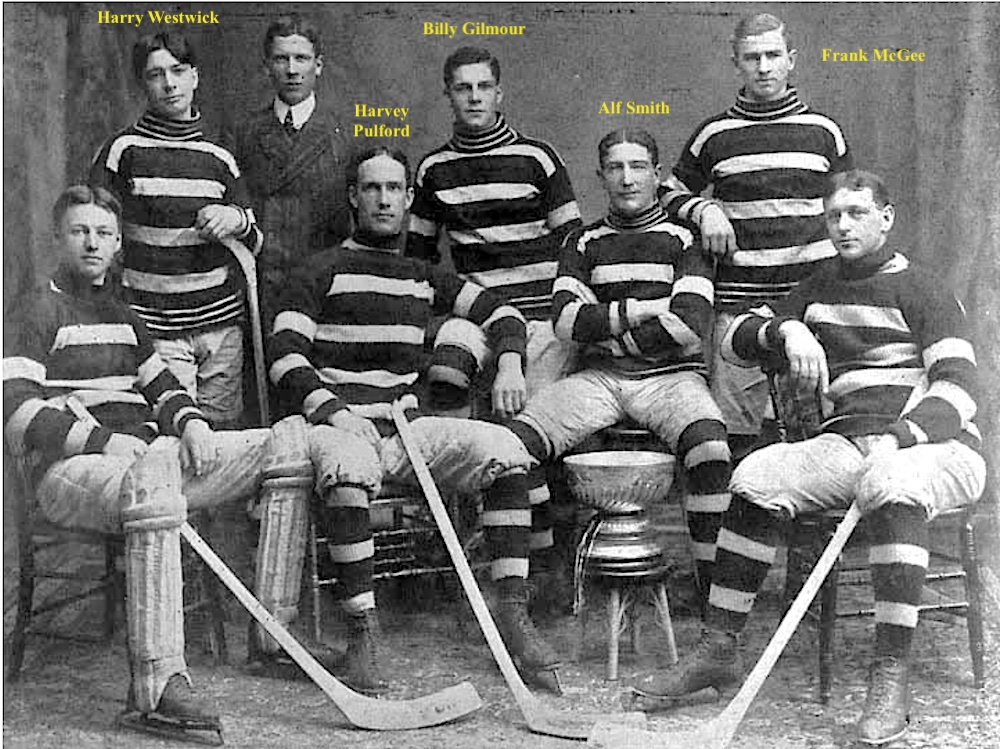

Since writing last week about the Gilmour brothers, I’ve been spending some of my lockdown time trying to find the story of how Billy Gilmour and his daughter escaped from Nazi-occupied France. If their account actually appears somewhere in print, perhaps it was told in an Ottawa or Montreal newspaper that isn’t available online. But, I have been able to piece together from other sources quite a bit of what might have happened.

According to stories in Ottawa papers in the 1930s, Billy Gilmour did own a house in Paris. His daughter, Gerna Gilmour, was trained there to play piano by Yves Nat, a French pianist and composer. But Billy and Gerna also spent time in the south of France, in Bayonne and Saint-Jean-de-Luz, on the Bay of Biscay, between Bordeaux and the border with Spain.

In a story about Gerna returning to Canada after the War to live in Montreal that appeared in the Gazette on September 14, 1946, it’s noted that she (and perhaps her father?) had escaped from Bayonne after the Petain armistice. This was the “peace treaty” negotiated with Hitler in June of 1940 by the collaborating Vichy regime in France under World War I hero Marshall Philippe Petain. It was signed on June 22 and went into effect on June 25.

Throughout that month, Britain was actively doing what it could to evacuate troops and civilians, most notably from Dunkirk in the early days of June, but all across the country. Evacuations of British and Polish troops, as well as other foreign civilians, from around Bayonne began on June 19. This was part of Operation Ariel, sometimes called Aerial. (The evacuation of Dunkirk was known as Operation Dynamo. Operation Cycle was the evacuation from Le Havre.)

Many of those fleeing Bayonne went first to Saint-Jean-de-Luz, where the evacuation concluded at 2 pm on June 25, just after the deadline set by the Germans in the terms of the armistice. Two Canadian warships, the HMCS Fraser and the HMCS Restigouche, took part in the rescue, but later that night, the Fraser was accidentally rammed by a British ship, the Calcutta. Neither had lights or radar, but they were moving at closing speed of 34 knots per hour. The Calcutta tried to swing starboard to avoid a collision. The Fraser went to port, reversing its engines but to no avail. The two ships struck. The Fraser was cut in half and began to sink.

The article is from the Gazette on January 6, 1942.

There were 115 crew members rescued by the Restigouche and other ships that night, but 45 men were lost.

It’s unclear if there were civilians on the Fraser, but there were probably some. Newspaper accounts from the time mention the losses to the crew, and the names of those rescued, but there likely hadn’t been time to compile any lists of civilians on board. Even so, Georges Vanier, Canada’s minister to France (and later the first French-Canadian to serve as Govenor-General of Canada) was there.

Frank Millan was an able seaman aboard the Fraser and he told his story in the Victoria Times Colonist on May 5, 1985.

“We were somewhere off Bordeaux,” he remembered. “We’d been down to the fishing port of Saint-Jean-de-Luz to pick up Georges Vanier…. The Germans were on their way in when we took off.”

It was shortly after 10 p.m. when the Fraser was rammed by the Calcutta.

George Garman was an ordinary seaman aboard the HMCS St. Laurent who had friends on the Fraser and the Restigouche. He told the story to the Salmon Arm (British Columbia) Observer on November 5, 1997. Garman says the British Admiral of the Fleet ordered the captain of the Restigouche to “disregard survivors and carry on with her duties.” Despite the threat of a court martial, the captain refused. According to Garman, he said “this is a Canadian ship and there are Canadian sailors in the water and I am picking them up.”

There are pictures of the Fraser available from several sources.

A story in the Red Deer (Alberta) Advocate on June 18, 1965, says the Restigouche threw wartime discretion aside and played lights on the water, searching for missing men. “They rescued everyone alive,” said retired Rear-Admiral Wallace B. Creery, the skipper of the Fraser that night.

In the Red Deer account, Georges Vanier is mentioned as being one of 15 diplomats found, along with British Ambassador Sir Ronald Hugh Campbell, “wallowing in a sardine shack in heavy rain off the Bordeaux coast.” He was taken by the Fraser to the British cruiser Galatea. Most of the refugees onboard the Fraser were transported to another ship. It’s noted that Mme. Vanier was also in France and that she was among the refugees who poured into Saint-Jean-de-Luz, but that she got back to England aboard “a slow tramp steamer.”

Was there any chance that Billy and Gerna Gilmour were on the Fraser or the Restigouche? Had they been in Paris when Georges Vanier and his Canadian diplomatic party fled the French capital for the south of France a few days before the Germans occupied the city on June 14?

Even if they were with that Canadian civilian delegation, the chances are greater that the Gilmours left from Saint-Jean-de-Luz in a manner more similar to Mme Vanier than to her husband. Still, it’s possible that they were transported from the Fraser to the Galatea. At this point, I don’t know. But if they were anywhere in the Bay of Biscay that night, as they very well might have been, it would have every bit the “harrowing” experience that the stories I’d found before about Billy Gilmour and his daughter’s escape had told of.