Thirty-five years (and two days) ago, on January 24, 1981, Mike Bossy of the New York Islanders scored his 50th goal of the 1980-81 season. He did it just 50 games. Wayne Gretzky would obliterate this unofficial record with 50 goals in 39 games the next season, but we had no way of knowing this at the time, so it was all pretty exciting!

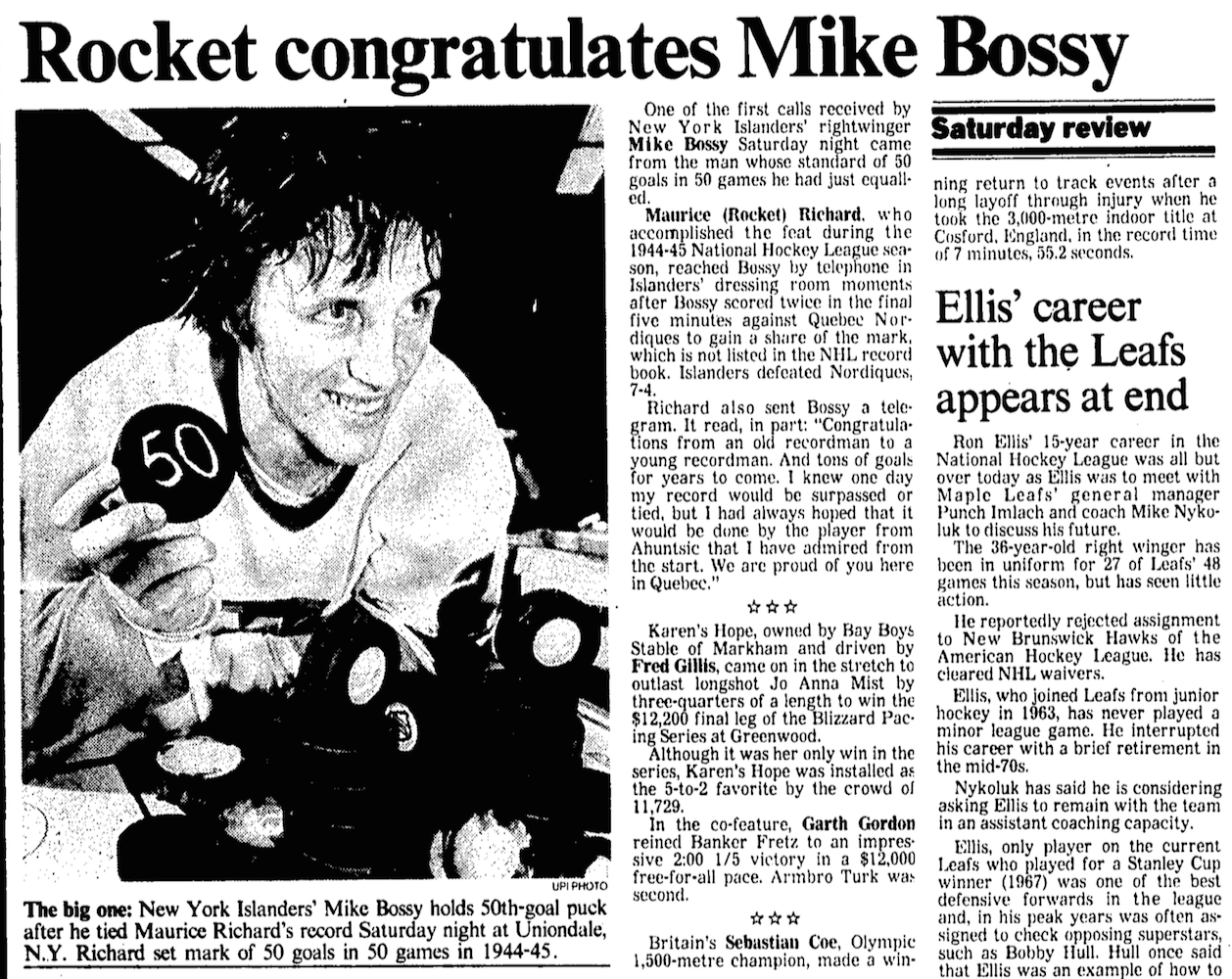

I was definitely caught up in the race as both Bossy and Charlie Simmer of the Los Angeles Kings took their shot at the 50-50 milestone. Simmer fell just short, with three goals in a 6-4 afternoon victory over Boston that same January day to give him 49 goals in 50 games. Bossy had reached 48 goals through 47 games but was shutout in two straight, and then for two periods that Saturday night against the Quebec Nordiques. He finally scored #49 with 3:10 remaining in the third, and then got #50 with just 1:30 to go. By that time, Hockey Night in Canada had gone live to the game, so I was watching when Bossy scored it. It was quite a moment.

Entering the 1980-81 season, there had been 23 players who’d scored 50 goals in a season since Maurice Richard had first done it in 1944-45. Many, like Bossy, had reached the milestone more than once. But none until that night had managed to match the Rocket’s feat of 50 goals in just 50 games.

Twenty years before Bossy, in the 1960-61 season, Frank Mahovlich, Dickie Moore and Boom Boom Geoffrion were all in the hunt to join Richard as the only 50-goal scorers in NHL history. At the time, there were those who claimed that even if one of them made it (Geoffrion was the only one who did), the record would be tainted because the NHL season was then 70 games long. Richard was not among those who saw it that way.

On January 25, 1961 – with Toronto’s Frank Mahovlich having scored 37 goals in 46 games – Richard spoke about his 50-goal record. “Naturally, I’d rather see someone on the Canadiens do it first,” he said, “but what does it matter? Records are meant to be broken, aren’t they?” When asked about scoring 50 in 70 games versus the 50 he’d played, Richard didn’t see any issue. “The record is for most goals in a season,” he said, “not in so many games. After all, Joe Malone once scored 44 goals in 22 games.”

Joe Malone had actually scored his 44 goals while playing in just 20 of 22 scheduled games during the NHL’s inaugural season of 1917-18, but Malone was certainly supportive when the Rocket broke his record in 1944-45. He was at the Forum on February 25, 1945, when Richard netted #45 in his 42nd game and the next day in a bylined article in the Montreal Star, Malone wrote that Richard:

“is one of those players that comes along every once in a while, and I hope he goes on to even greater feats… Ever since he became such a talked-about player I have followed his career with interest… I am happy that my record was broken by such a fine young player. They say he is a fine-living boy, who keeps in tip top shape.”

Richard wasn’t able to be there when Geoffrion became hockey’s second 50-goal scorer on March 16, 1961.

He wasn’t there when Bossy scored 50 in 50 in 1981 either, but he phoned him after the game and sent a telegram of congratulations. Richard was particularly pleased that Bossy was from suburban Montreal. “In fact,” he told reporters later, “I told the Canadiens to draft him in 1977, but they wouldn’t listen to me. They said he wasn’t good enough defensively.”

“What the Canadiens didn’t understand,” Richard added, “is when you can score goals like he can, you don’t watch your man. He watches you.”

Interestingly, Billy Reay said almost the exact same thing about Richard when he left the Canadiens organization to become coach of the Toronto Maple Leafs in the spring of 1957. In discussing his philosophy of letting a player do what he does best, Reay said: “Take Rocket Richard as an example. He’s so tremendous at carrying the puck in and scoring goals that no one ever worries about his defensive ability. Generally, the man covering him is too busy to think about scoring.”

Coaches don’t think like that anymore, and it’s a big reason why on January 26, 1981, Marcel Dionne led the NHL with 90 points in 50 games (Gretzky had “only” 83 in 47) and Bossy had his 50 goals, while today Chicago’s Patrick Kane leads with 30 goals and 73 points in 52 games … which is actually pretty high by recent low-scoring NHL standards.

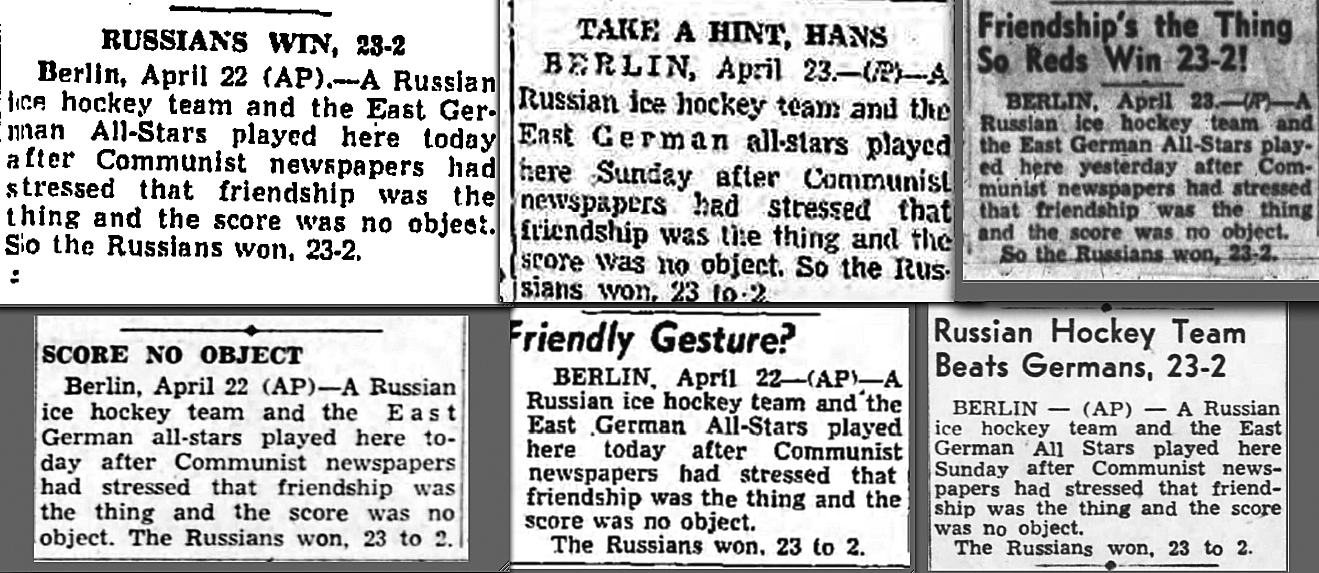

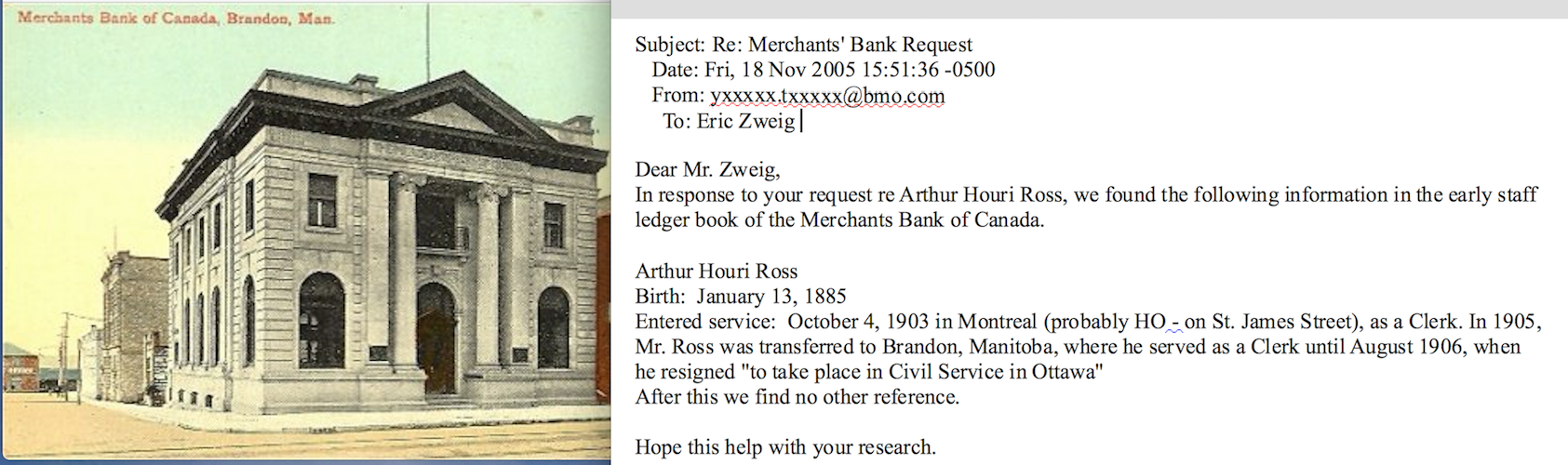

I was amazed that the Bank of Montreal HAS an archivist, and that she could find this …

I was amazed that the Bank of Montreal HAS an archivist, and that she could find this …