There hasn’t been much said lately about the news coming out at the end of July that the NHL will investigate claims made in a series of tweets by the estranged wife of Evander Kane that Kane not only bet on NHL games but that he had thrown a number of games while playing for the San Jose Sharks. Kane is known to have a gambling problem, and to be deeply in debt. Still these accusations have yet to be proven. But legal gambling is a big business, so sports leagues continue to cozy up to casinos and online betting sites, and the Canadian government has now legalized single-sports wagering effective tomorrow.

Hockey has no history of gambling scandals to rival anything like the Black Sox Scandal of 1919 when eight members of the Chicago White Sox were banned for life from baseball for conspiring with gamblers to rig that year’s World Series. (This was actually just the biggest of many gambling scandals to plague baseball in the 1910s and ’20s.) Still, hockey has had its own problems. Most notably, in 1948, when Billy Taylor and Don Gallinger of the Boston Bruins were given lifetime suspensions (eventually rescinded, but not until 1970) for feeding information about their team to gamblers and for betting on games. Possibly even against their own team. Unlike Kane or the Black Sox, there was never any indication that the two players had conspired to throw games.

Perhaps the first gambling scandal in hockey history occurred in Toronto back in 1915.

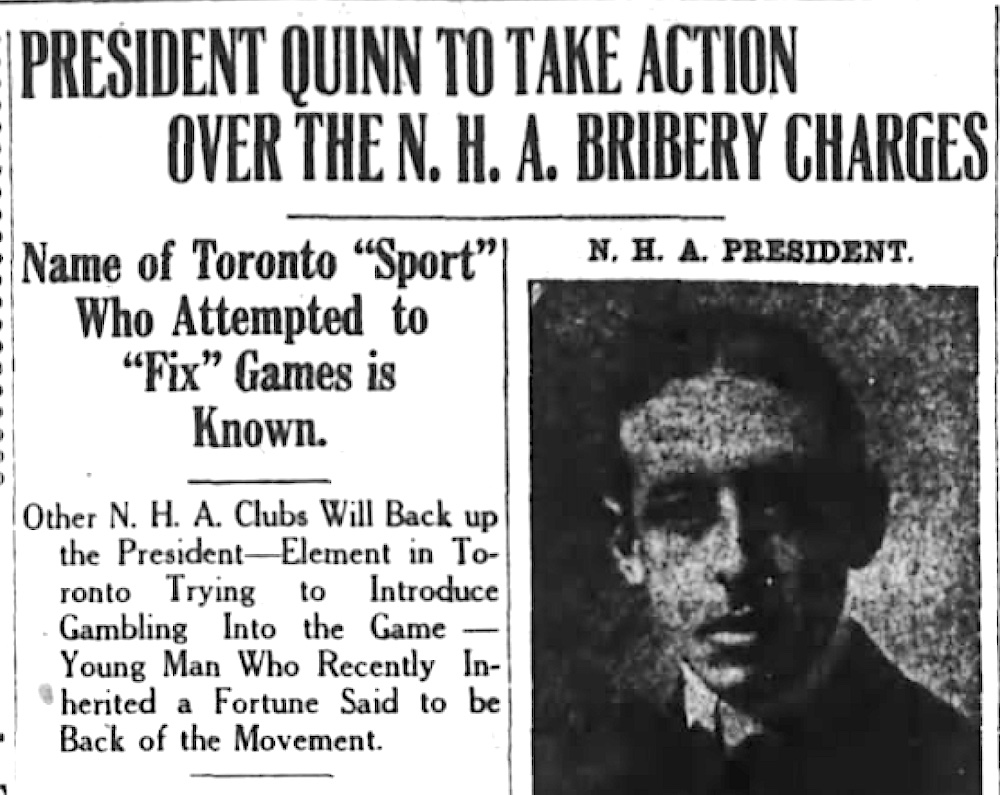

A story reported out of Montreal on February 22, 1915, appeared in several newspapers across Canada the next day. It was about bribes (and other efforts) made to players in the National Hockey Association (forerunner of the NHL) by gamblers. The news broke when players on the Quebec Bulldogs told their story while passing through Montreal on their way back home after a game in Toronto. The story claimed that Harry Mummery of the Bulldogs, and team trainer Dave Beland, had been offered bribes before a Saturday night game on February 20, 1915, to let the Toronto Shamrocks win.

Mummery was said to have been offered $1,000 to throw the game. Beland was reportedly offered $50 to deliver a spiked drink to a few Quebec players. Both refused, and reported the incidents to the team manager, Mike Quinn, who reported it to NHA president Emmett Quinn.

Newspapers noted that it was not the first time something like this had happened in Toronto. Another report mentioned attempts to bribe players on the Canadiens and the Toronto Blueshirts. No names were mentioned, but Harry Cameron of the Blueshirts — a future Hockey Hall of Famer — was cited in a different vein.

“Last week,” said president Quinn, “a gambler in Toronto invited Cameron of the Toronto team out, and induced him to break training [ie, got him drunk] with the result that he was unfit to play that night. It was found out the gambler and his friend had bet a large amount on the opposing team.”

Nothing much really came out of all this in 1915. Lol Solman, owner of the Arena Gardens on Mutual Street, believed the stories had been greatly exaggerated. Still, the Toronto Telegram on February 23, reported that President Quinn had instructed all NHA managers “that any player shall be expelled who has been proven guilty of offering, agreeing, conspiring, or attempting to lose any game of hockey or in being interested in any wager thereon.” Quinn vowed that he was going to take action to stop this sort of thing.

Gambling may or may not have been stamped out at Toronto’s Arena Gardens and in the NHA back in 1915, but it would certainly be prevalent in the NHL at Maple Leaf Gardens in future. If there wasn’t gambling at the Gardens right from its opening in 1931, there would certainly be a so-called “bull ring” of bookies operating from a promenade behind the blue seats at one end of the rink soon enough.

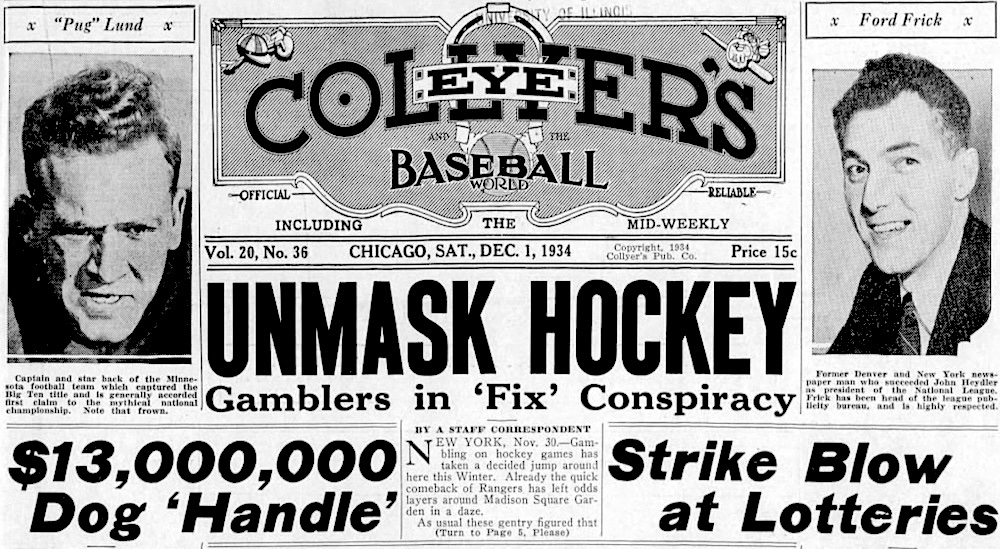

A Chicago newspaper called Collyer’s Eye and The Baseball World provided plenty of details in an issue on December 1, 1934. The paper noted that reports on hockey gambling were up all around the NHL early in the 1934–35 season. “There are even rumors that efforts have been made to [bribe] some of the goaltend[er]s.”

Montreal was said to be the long-time center of hockey gambling, but it was much quieter there that season than New York. Detroit was labeled as the new hot gambling mecca, with Boston only lukewarm. Nothing is said about Chicago, or St. Louis (where the Ottawa Senators had recently relocated), but it was noted that there was plenty of action on NHL games in non-league centers such as Kansas City, Missouri, and the Minnesota cities of Minneapolis, St. Paul, and Duluth. There were plenty of details about Toronto too:

“Toronto is a spot where one can get a bet down at any time. In fact, in the bull ring at Maple Leaf Gardens they will give you anything you want in the line of wagering accommodations, though they deal the nuts on Leafs. You can bet on goals, the most shots, or penalties. One favorite wager is that Leafs will score as much in one period as the other team does in the whole game.”

Other stories from other sources indicate Toronto was so rife with gambling that fans were known to place bets on whether the next spectator to be hit with a puck in the stands would be a man or a woman!

Efforts weren’t made to clean out the bull ring in Toronto until 1946, after Maple Leafs star defenseman Babe Pratt was expelled from the NHL for gambling. (Pratt would be reinstated after missing five games and forfeiting his salary from January 29 through February 14.)

But even at that, in an article about the Gardens in Maclean’s magazine on March 1, 1958, John Clare wrote: “in an emergency, as at playoff time when the public need for the service is greatest, the bookies have been known to drift back and ply their trade with the same discretion and high ethical standards that made them a tradition in less censorious times.”

For more on the bull ring, and the Toronto gambling scandals of 1915 and 1946 (and plenty more on a wide range of subjects!), look for my new book from Firefly Books, Hockey Hall of Fame: True Stories, which is due out this fall but already available for pre-ordering. For more on Evander Kane, keep an eye on the sports news. And if you’re a fan in Canada who loves to risk your money, it should be even easier for you now…