Though it won’t be out for a while, I’m currently working on an oral history of the Toronto Maple Leafs. Recent research turned up numerous references to the famed Kid Line of Joe Primeau, Busher Jackson and Charlie Conacher playing their first game together for Toronto on December 29, 1929. So, I figured, that was a perfect story for today. But – as is so often the case with old-time hockey facts – the true story wasn’t quite so simple.

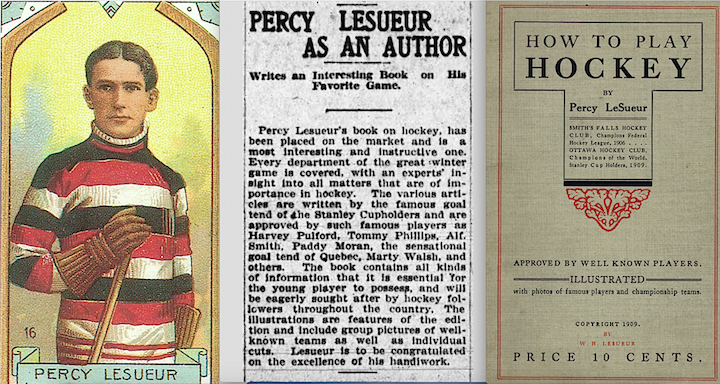

From left to right, Charlie Conacher, Joe Primeau and Busher Jackson.

Joe Primeau (born January 29, 1906) was the first of these young players to reach the NHL. He was 22, but Primeau played only a few games with the Maple Leafs in 1927-28 and 1928-29. Charlie Conacher (born December 20 1909) was more than a month shy of his 20th birthday when he joined the Leafs for the 1929-30 season. According to most accounts, right winger Conacher began his NHL career playing with center Eric Pettinger and left winger Harold (Baldy) Cotton. Soon, though, Primeau replaced Pettinger as the center on the line. Cotton was already 27 years old and in his fifth NHL season, but after the Maple Leafs beat the Detroit Cougars 1-0 on a Primeau goal on Saturday night, November 30, 1929, Toronto Star sportswriter Lou Marsh writing in the paper on Monday, December 2, referred to “Whizz-Bang Conacher, Slippery Joe Primeau and Harold Tonsilitis Cotton” as Conn Smythe’s “kid line.” Marsh uses lower-case letters (as he would for a while yet), but this is the first use of the phrase I’ve come across.

A few days later, on December 6, 1929, the Maple Leafs signed Harvey (Busher) Jackson. Born on January 17, 1911, Jackson was still just 18 years old and was the youngest player in the NHL when he made his Leafs debut the following night against the Montreal Canadiens. Jackson and Conacher had been teammates with the Toronto Marlboros the past two seasons, and were immediately paired up with the Leafs – with Primeau as their center.

To be honest, it’s unclear if Primeau, Jackson and Conacher played the entire game together on December 7, 1929, but they were certainly the combination Conn Smythe turned to with the game on the line. As Lou Marsh wrote in the Star on Monday, December 9:

“Apart from the fact that the Leafs were lucked out of a win the contest did not wow the customers except in the last four minutes. But in that four minutes the customers got even with the box office. The score was 1-0 then – had been since the second minute of the second period when Hap Day deflected a Lepine to Mantha pass into his own net – and the Leafs were staging a peppery three-ply attack upon the Canadien’s citadel… Manager Smythe hurled reinforcement after reinforcement at the unbroken red-clad troops. First he had the kid line out – Harvey Jackson, the newest recruit, Joe Primeau and Whizz Conacher – and they whirled in upon the Canadien defence like vagrant cyclones… It did not look as if they could miss the tying goal. How Hainsworth kept that puck into open circulation no one knows – but he did.”

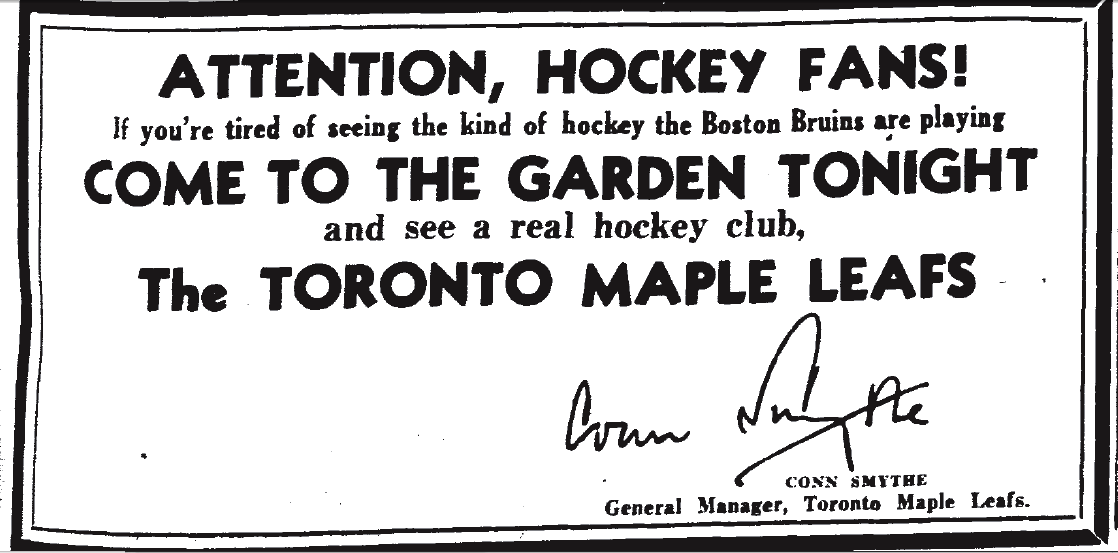

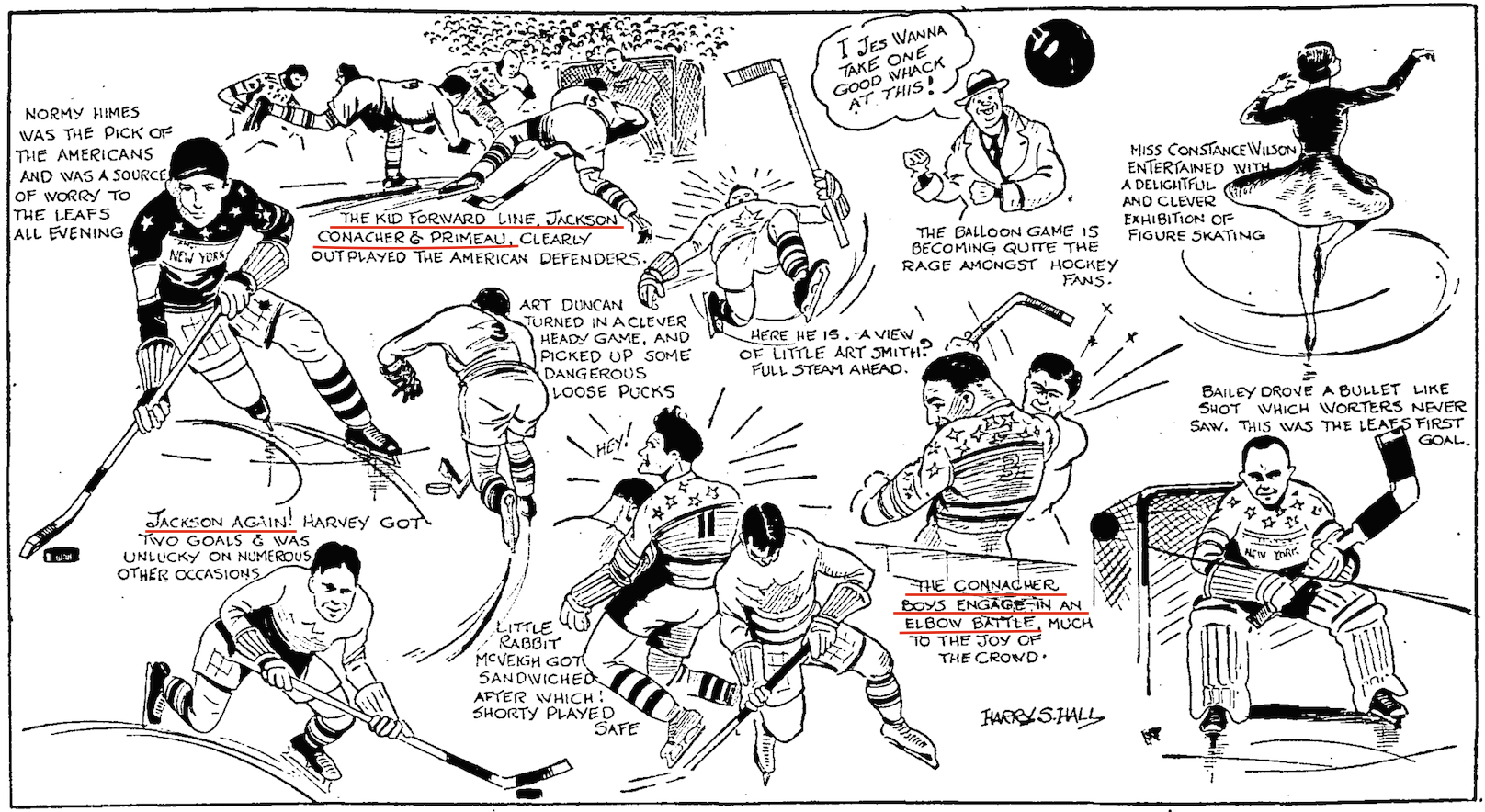

From the Toronto Star, Monday, January 20, 1930.

Not only did the Leafs lose 1-0, but Jackson appears to have been hurt. He wasn’t in the lineup when the Leafs visited the New York Americans on December 10 and on December 12 the Globe in Toronto noted that he was “laid up with a bad leg.” Jackson missed three more games before returning to face the Pittsburgh Pirates on December 21, but it appears that he lined up with Eric Pettinger and Art Smith that night, while Primeau and Conacher stayed with Cotton. Conacher was reported as having played despite being sick, and he was out of the lineup when Toronto was defeated 6-2 in Boston on December 25.

Cotton appears to have been hurt in the Christmas night game, and when Toronto was in Chicago on December 29, Smythe was forced to juggle his lines again. The Maple Leafs beat the Black Hawks, “and what pleases Horace H. Public the most,” wrote Marsh in the Star, “is the fact that the Leafs’ kid fowards – Conacher, Primeau and Jackson – delivered on target.” Primeau set up Jackson midway through the second period for a 3-1 Toronto lead and after Chicago rallied to tie it in the third, Conacher took a pass from Primeau and beat Charlie Gardiner to give the Leafs a 4-3 victory.

While it’s clear the December 29 game wasn’t the first time they’d played together, there was no splitting up the threesome after that! The Maple Leafs beat the Montreal Maroons 5-3 on New Year’s Day, and the Globe noted:

“The feature of the game was the work of the ex-Marlboro stars. Jackson and Conacher worked well with Primeau and they provided some of the best attacking plays of the game… That ‘kid’ forward line of Primeau at center and Conacher and Jackson on the wings showed some pretty hockey.”

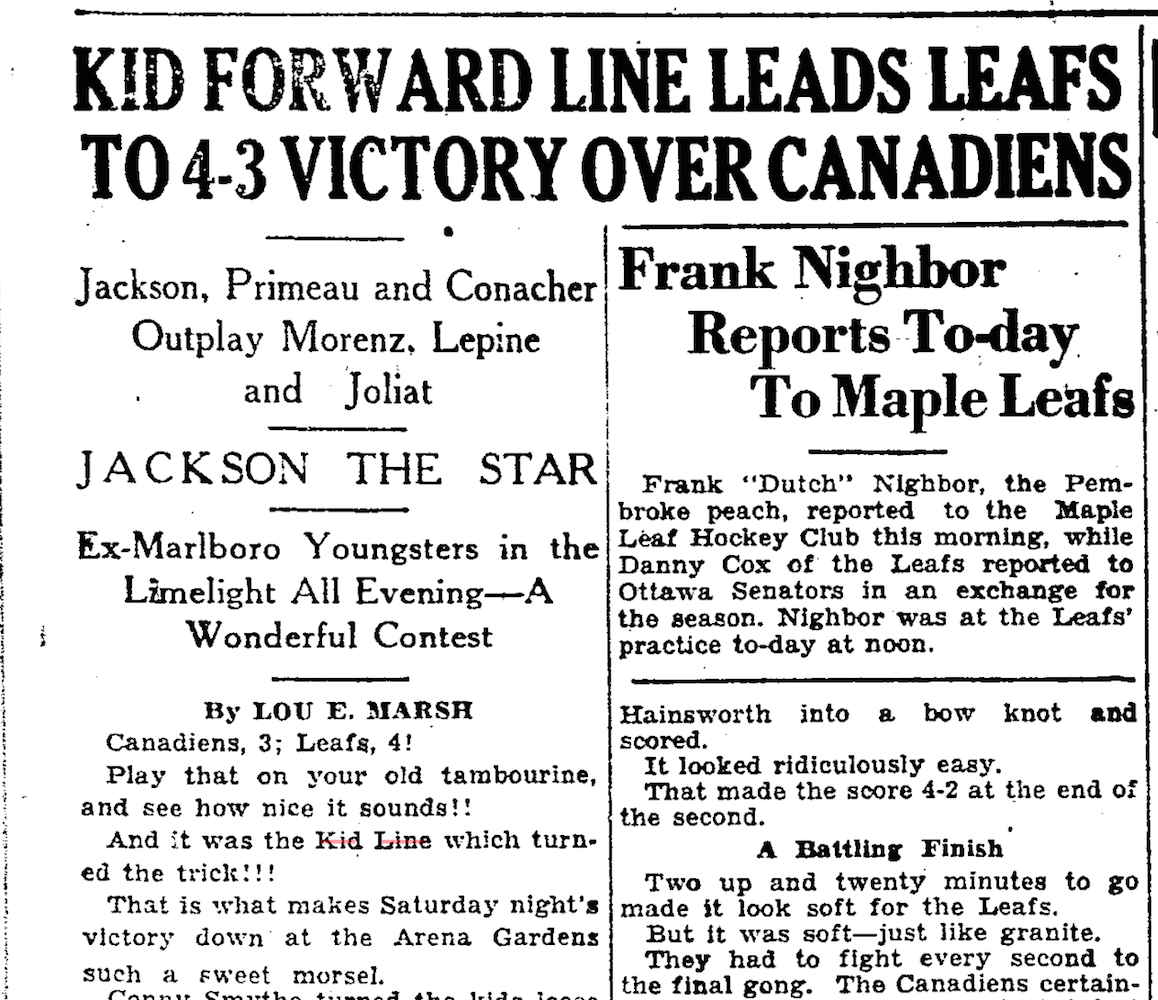

Three nights later, when the Leafs beat the Canadiens 4-3 on January 4, 1930, the Kid Line earned headlines … and capital letters!

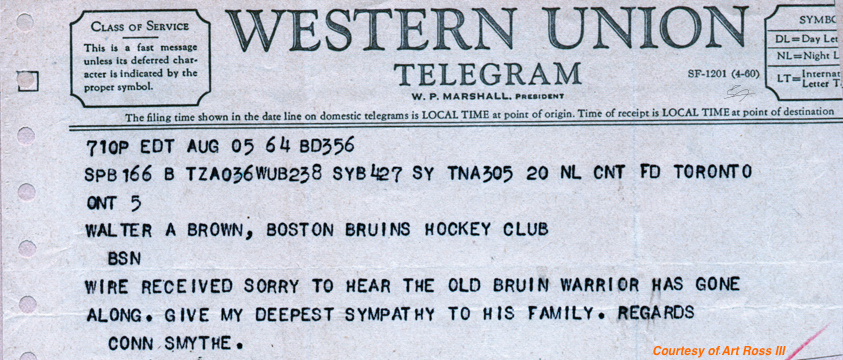

From the Toronto Star, Monday, January 6, 1930.

The rest is history, with scoring titles and All-Star berths to come for Primeau, Jackson and Conacher, and Stanley Cup championships and a nation-wide fan frenzy (thanks to Foster Hewitt’s radio broadcasts) soon to follow.