The NHL’s newest team officially got a name last week when it was announced that the expansion franchise in Las Vegas for 2017-18 will be known as the Vegas Golden Knights. The official colours will be steel grey (for strength and durability), gold (because Nevada is the largest producer of gold in the USA), red (for the Vegas skyline and the Red Rock canyons of the nearby desert), and black (for power and intensity.) Grey, Black and Gold are also the colours of the United States Military Academy at West Point, whose sports teams are known as the Black Knights, and where the new hockey team’s majority owner Bill Foley graduated in 1967.

There have actually been professional hockey teams in Las Vegas since 1970, and serious interest in an NHL team since 2007. The current ownership group has been involved in the discussion since the spring of 2014. The NHL authorized a formal expansion process on June 24, 2015 and made applications available to interested parties that July. It was then announced on July 21, 2015, that Las Vegas and Quebec City had applied. Nearly a year later, on June 22, 2016, it was announced that Las Vegas would become the NHL’s 31st team. Five months later, the team got its name. In about 11 more months, they’ll play their first game.

Things moved a lot faster when the NHL first expanded back in 1924! Yes, teams had been added – and subtracted and relocated – prior to this, but the admission of a second Montreal team and the first U.S. club for the 1924-25 season (which saw the league grow to six teams – although not the so-called “Original Six”) was the first true expansion.

There had been internal talks for a few years already, but the first public indication that the NHL was considering the addition of American teams came in March of 1924 when Colonel John Hammond, representing Madison Square Garden of New York, and Charles Adams of Boston were invited to Montreal during the Stanley Cup playoffs. Reports on March 20, 1924, had Adams confirming that he’d purchased an option on a franchise for Boston. Little more is heard again until September 26, but by September 30, the Boston Arena had agreed to give ice to Adams for his new team, and Art Ross had agreed to serve as the coach, manager and vice president.

The NHL wouldn’t actually confirm the new entries in Boston and Montreal until October 12, 1924; the Boston Professional Hockey Association, Inc. wasn’t officially formed until October 23; and formal approval of the franchises didn’t actually come until the NHL’s annual meeting in Montreal, on November 1, 1924. Even so, the two teams would play their first games against each other in Boston just one month later– meaning there was no time to waste!

On September 30, 1924, it had been reported that Boston would take over the now-defunct Seattle franchise of the rival Pacific Coast Hockey Association, but that story quickly proved false. Ross would sign a few over-the-hill PCHA veterans for the new Boston team, but mainly he was on the road for the next few weeks trying to recruit promising amateurs. Most of the players he assembled met up in Ross’s hometown of Montreal on November 14, 1924, and proceeded to Boston together by train. The team also got its name that day, and its colours too. Brown and yellow, same as Adams’ chain of grocery stores. (Black would replace the brown in the Bruins uniform in 1934–35.)

“An interesting item is connected with Pres. Adams’ partiality towards brown as the team color,” noted that day’s Boston Globe. “The pro magnate’s four thoroughbred [horses] are brown … his Guernsey cows are of the same color; brown is the predominating color among his Durco pigs on his Framingham estate, and the Rhode Island hens are brown, although Pres. Adams wouldn’t say whether or not the eggs they lay are of a brown color.” Browns was even considered as the team nickname, but Adams was concerned that people would call them the Brownies, which struck him as childish. The team name, of course, would be the Bruins.

The stories surrounding the Bruins name are all pretty much the same. Charles Adams held a contest, but had very definite ideas about what kind of name he wanted. He wanted the name to relate to “an untamed animal.” He wanted the animal to be big, strong, ferocious and smart. (Of course, it wouldn’t hurt if that animal happened to be brown!) A secretary in the team office is usually given credit for coming up with Bruins – which comes from an old English term for a Brown bear first used in a medieval children’s fable. In his book “The Bruins” famed hockey writer Brian McFarlane specifically names Bessie Moss, whom he says was a transplanted Canadian working for Art Ross in Boston. When I was working on my Art Ross biography, I asked McFarlane about the story – which had proven impossible for me to confirm. He was pretty sure he’d come across it in either an old book or newspaper story some time during his hockey travels in the 1970s, but no longer had the source among his collection.

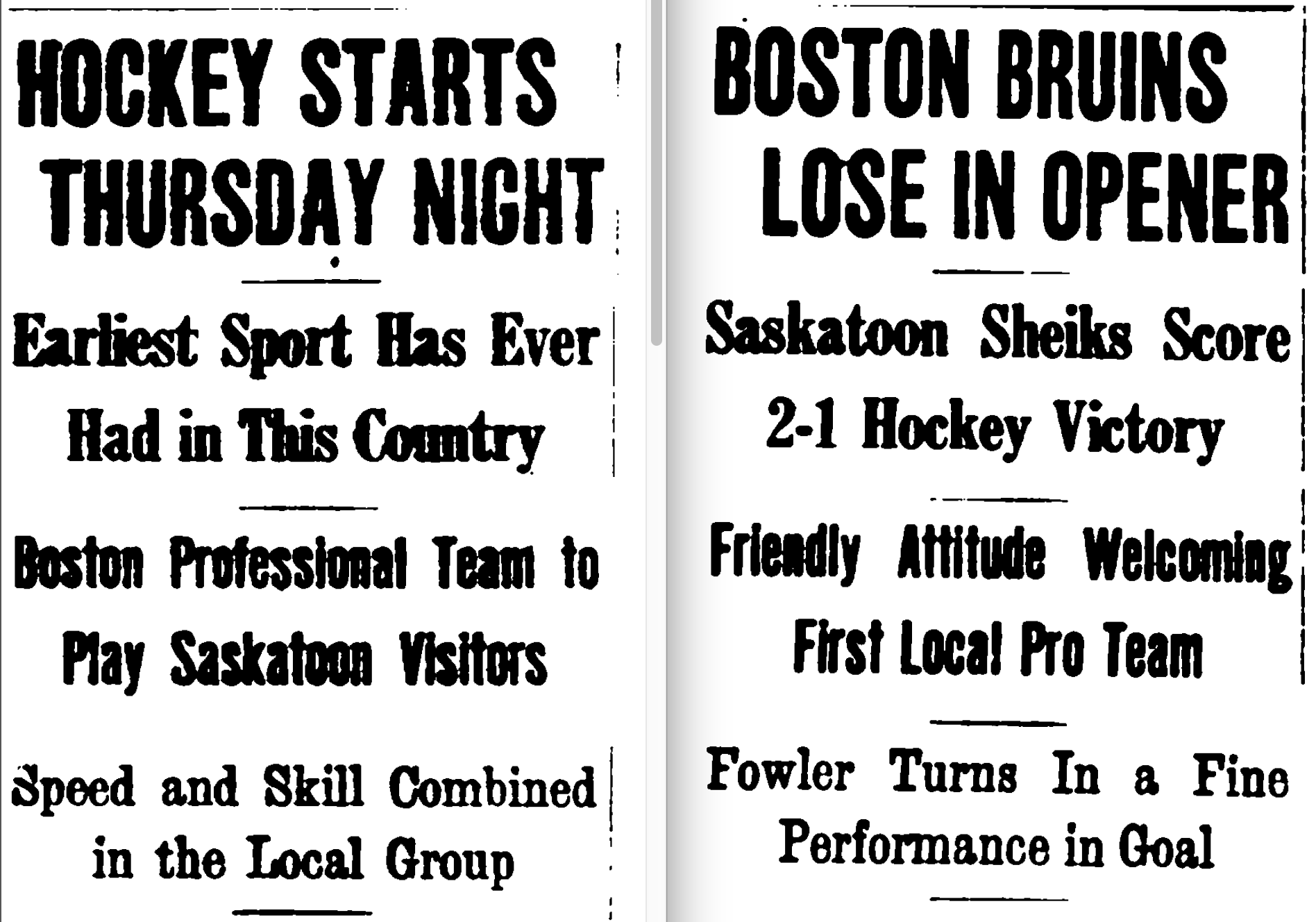

Whoever and however they got the name, the Bruins hit the ice for their first practice on November 15, 1924, and played their first game on Thanksgiving night, Thursday, November 27. It was an exhibition game against the Sasktoon Sheiks of the Western Canada Hockey League. Boston lost 2-1. They would beat their expansion cousins from Montreal (who were not officially named the Maroons until the following season) by the same 2-1 score in their first NHL game on December 1, 1924. Still, it would be a long, trying, season for the Bruins, who finished that first year with a record of 6-24-0. Montreal was only slightly better at 9-19-2.

The NHL will be counting on a better showing by Vegas – but they’ll be hard pressed to match the Maroons, who improved so quickly they won the Stanley Cup in their second season, or the Bruins, who were champions by year five.