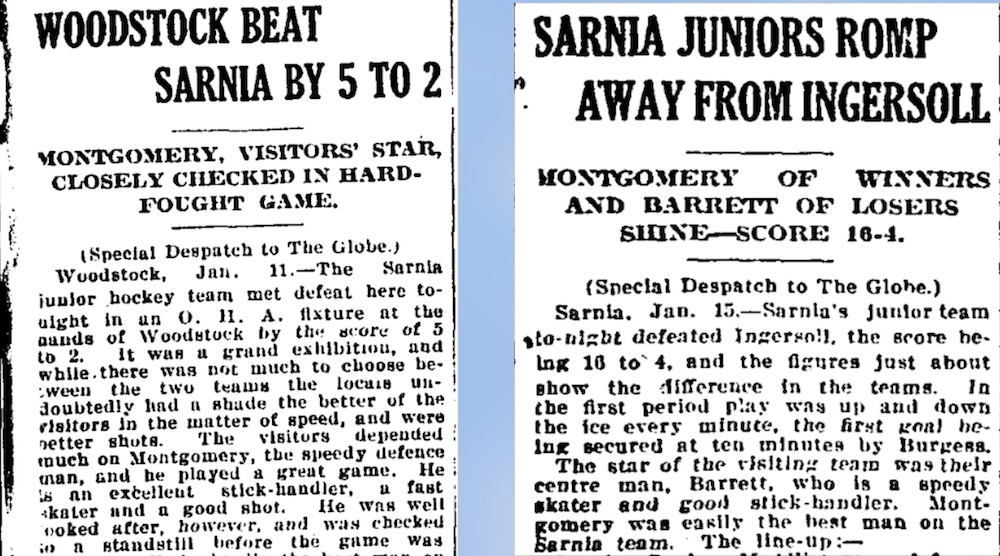

Though many stories — then and now — claimed he was the first of his religion to play in the NHL, Alex Levinsky wasn’t quite the Jewish Jackie Robinson. At least three players, and perhaps a fourth, preceded him. There was Sam Rothschild and Joe Ironstone, both from 1924 to 1928, Moe Roberts in 1925, and also Charlie Cotch in 1924, who may have been born Jewish, but if so turned his back on his faith. Still, Alex Levinsky was the first Jewish player to have a full-fledged NHL career (nine seasons), and he was definitely recognized as — and embraced being — Jewish.

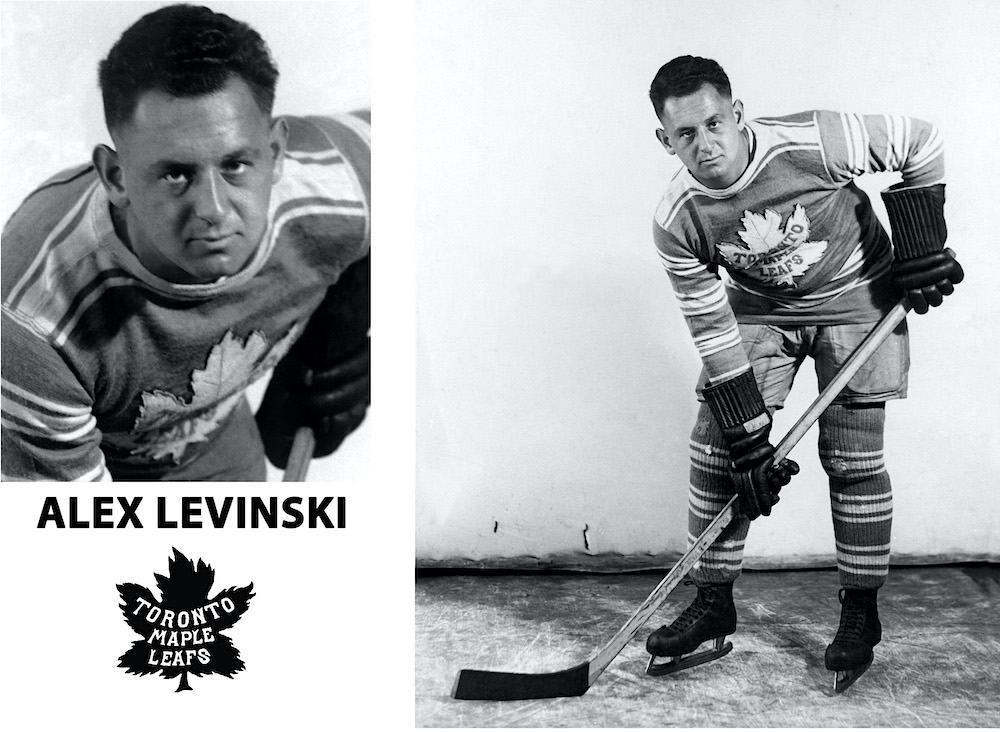

Playing with the Maple Leafs in his hometown of Toronto gave Levinsky a high profile as a Jewish hockey player during a time of open anti-Semitism. And even if he wasn’t the Jewish Jackie Robinson, he may well have been the Jewish Lionel Conacher. Ten years younger than Conacher — who was also from Toronto and would be named Canada’s outstanding athlete of the first half of the 20th century in 1950 — Levinsky is worthy of the comparison.

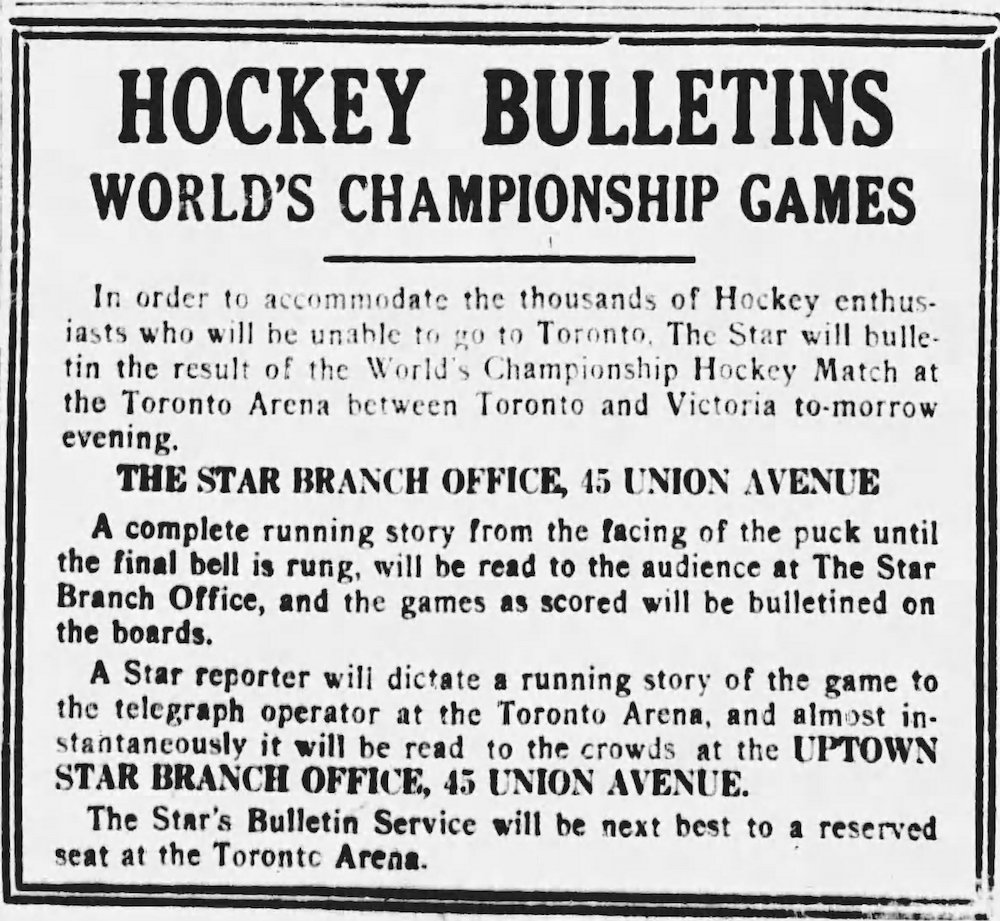

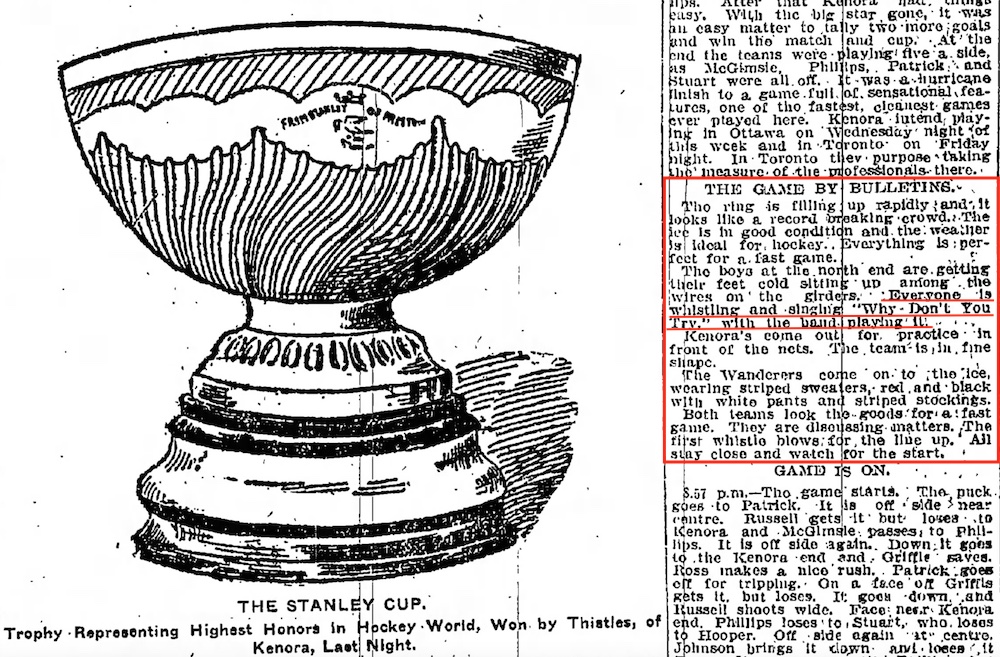

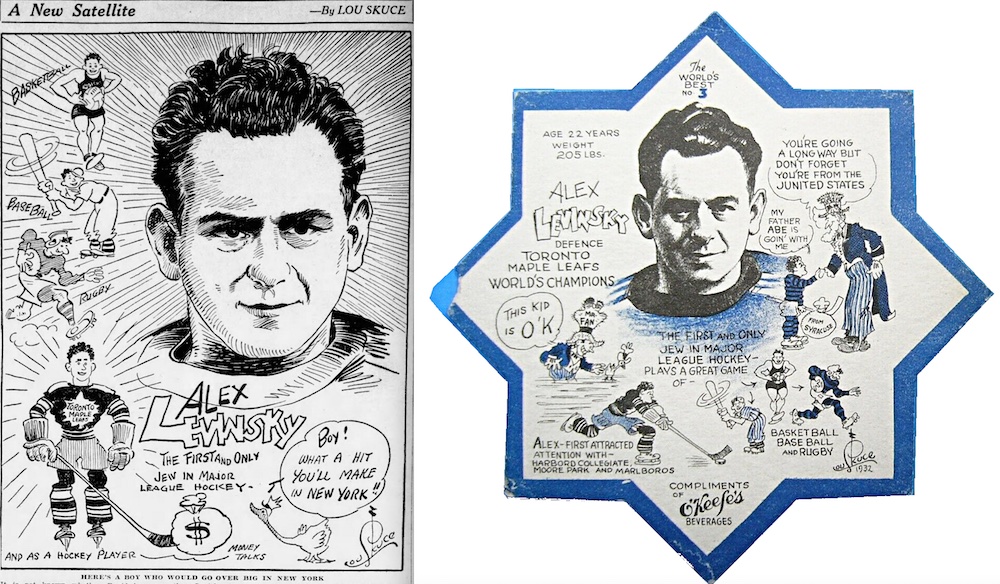

on March 20, 1931. The second was part of a series of Maple Leafs coasters

produced by O’Keefe’s for the 1932–33 season. (Coaster courtesy of Irv Osterer.)

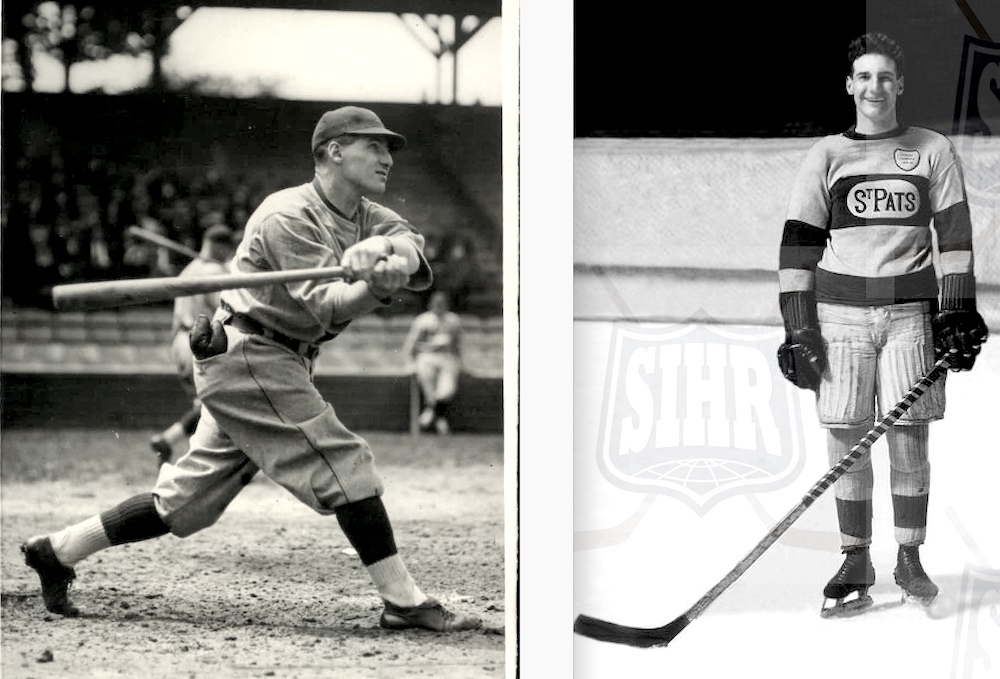

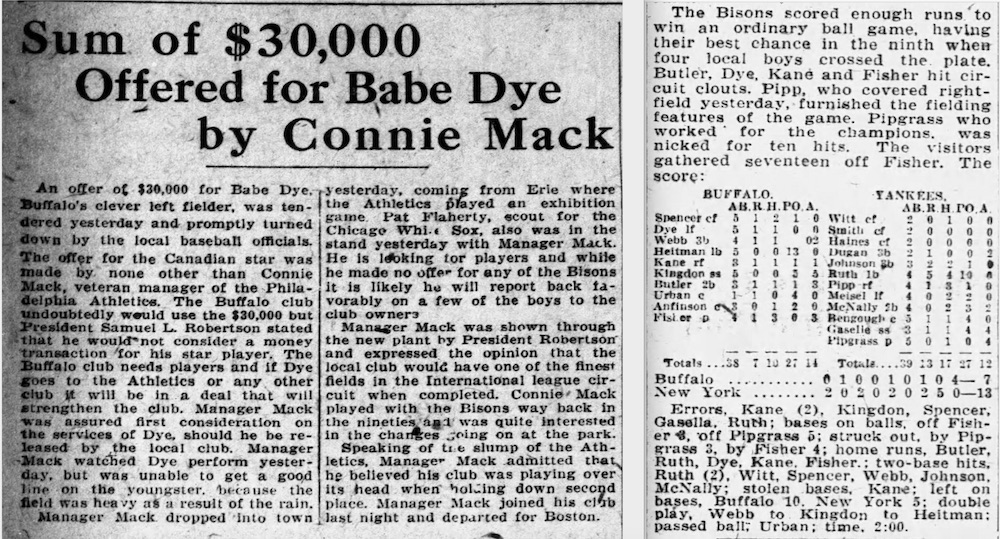

Levinsky’s son, Richard, says Alex was an even better baseball player than he was a hockey player. He was a pitcher and a hard-hitting outfielder who was offered a contract by the St. Louis Browns. Richard still has a letter from the Maple Leafs to his father allowing Levinsky to play baseball in the offseason, and while that was fairly common among hockey players of the time, Levinsky had also been a local basketball star and a football player in high school and university. He also starred in softball, was good at tennis and golf, and was apparently a strong swimmer. This isn’t just family pride talking, nor the hometown press lauding his many skills. A story in the Daily Eagle of Brooklyn, New York, on October 3, 1929, shortly after Levinsky had enrolled at the University of Toronto, refers to him as “probably the best all-around athlete in Toronto today.”

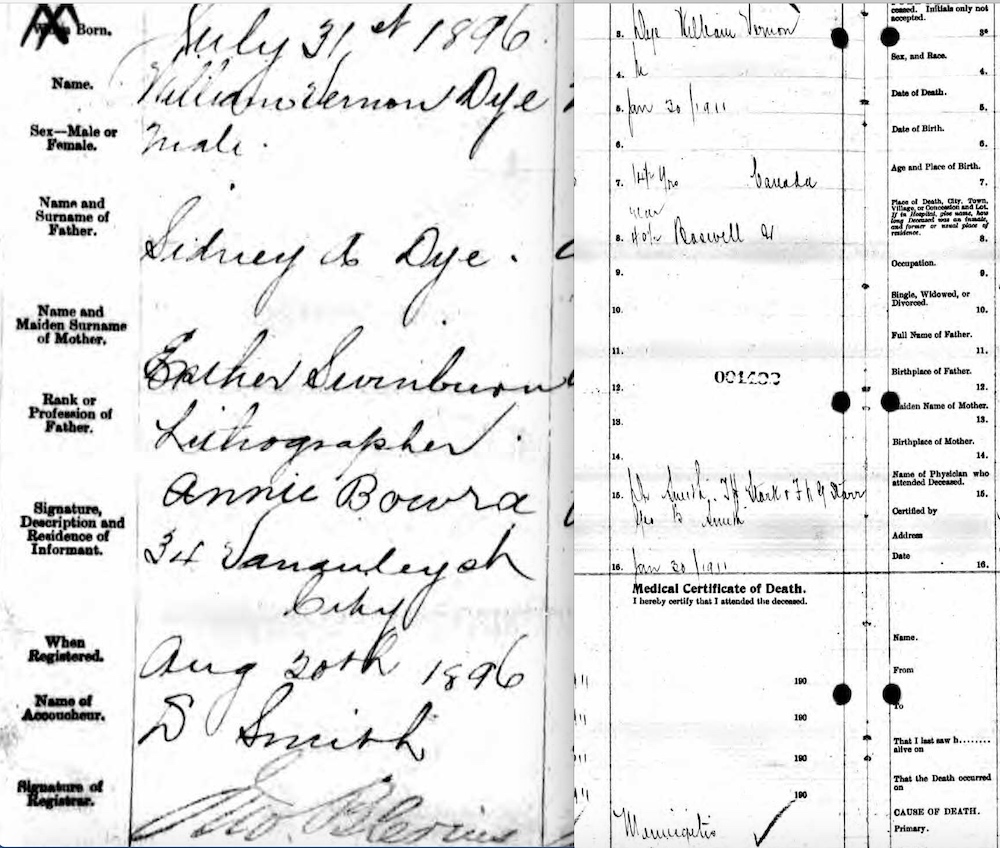

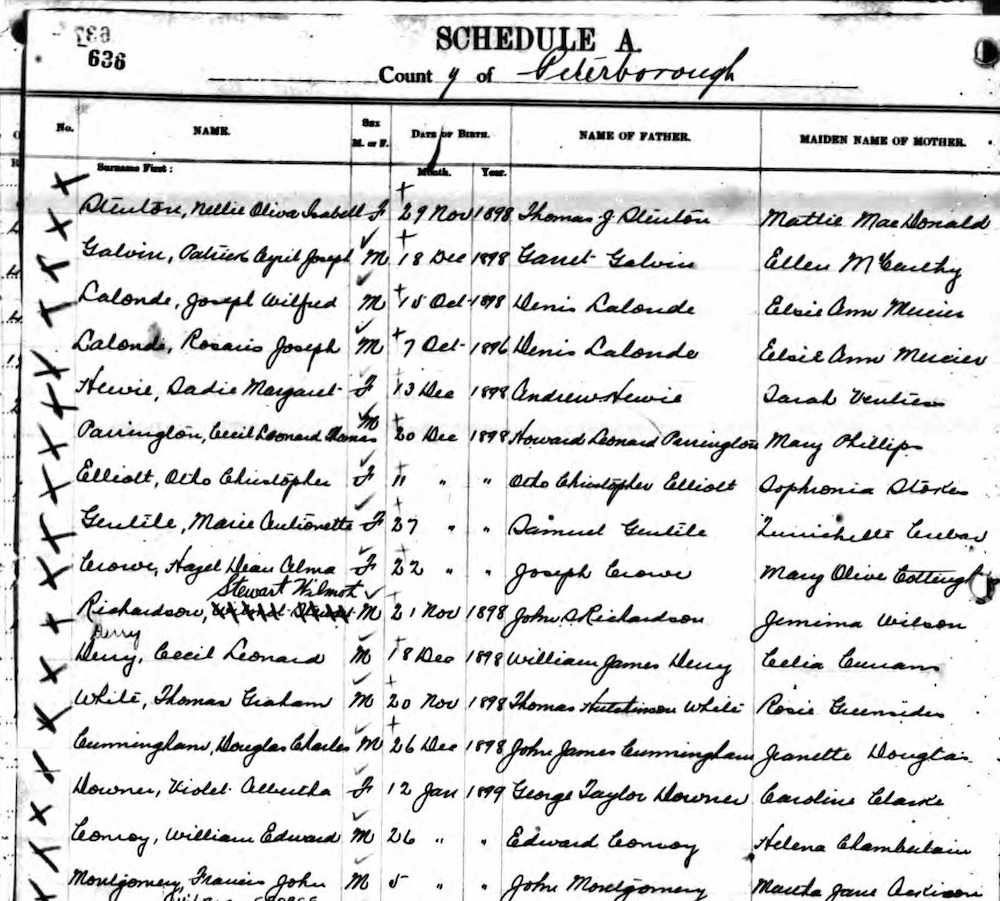

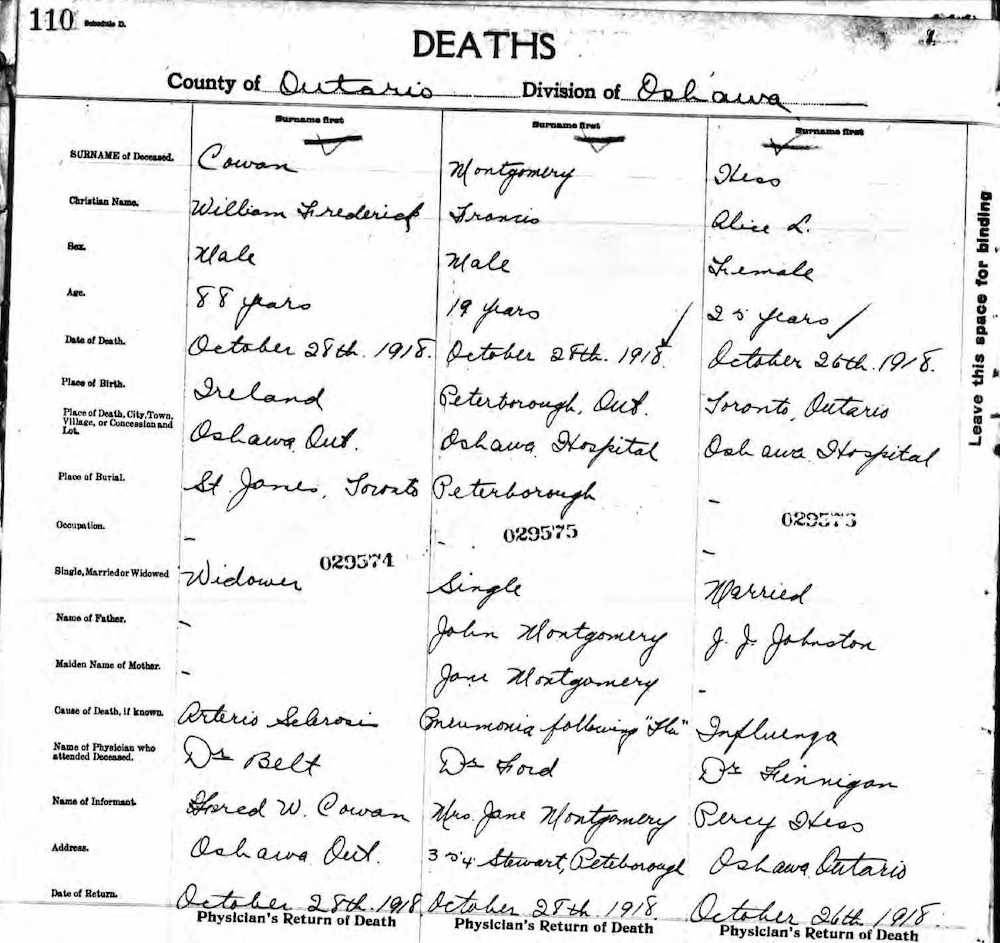

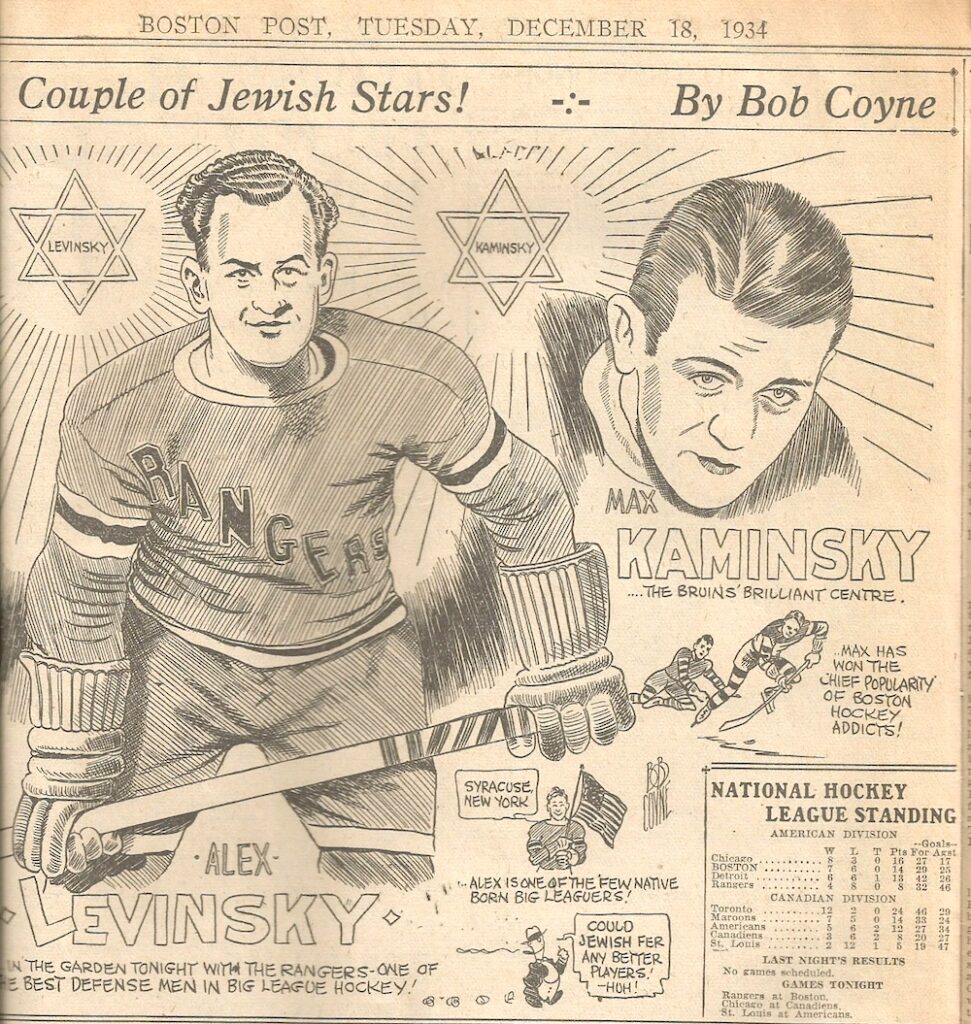

Alex Levinsky was born February 2, 1910, in Syracuse, New York. It was always known he’d come to Canada at a young age, but American newspapers often made it sound like he was an American. Technically, he was, but as Levinsky told Paul Patton of the Globe and Mail for a ‘Where are they now’ feature on November 11, 1985, “My mother was from [Syracuse] and she returned home to be with her mother when it came time to have me.”

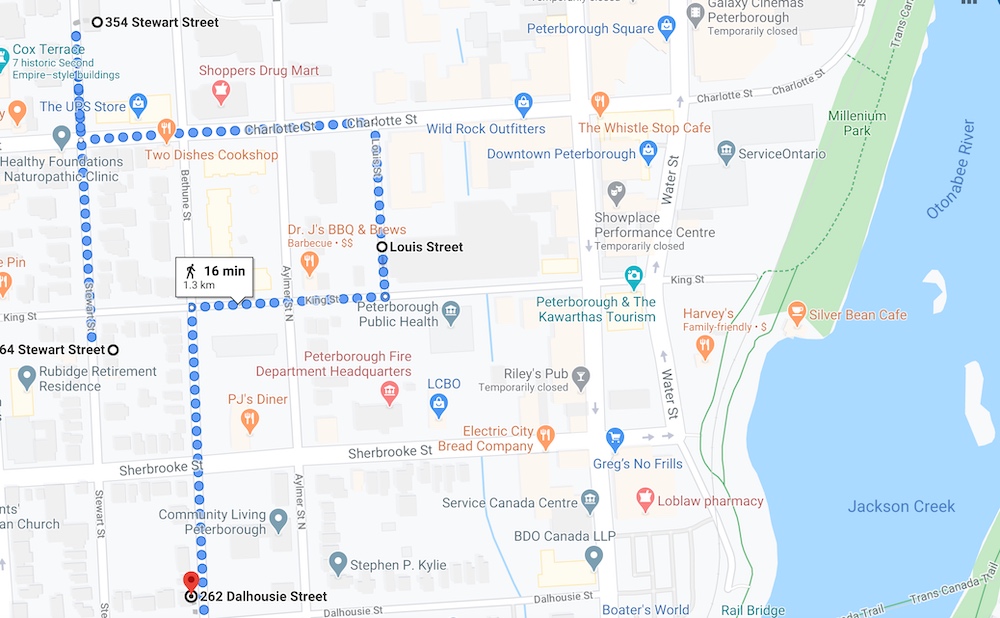

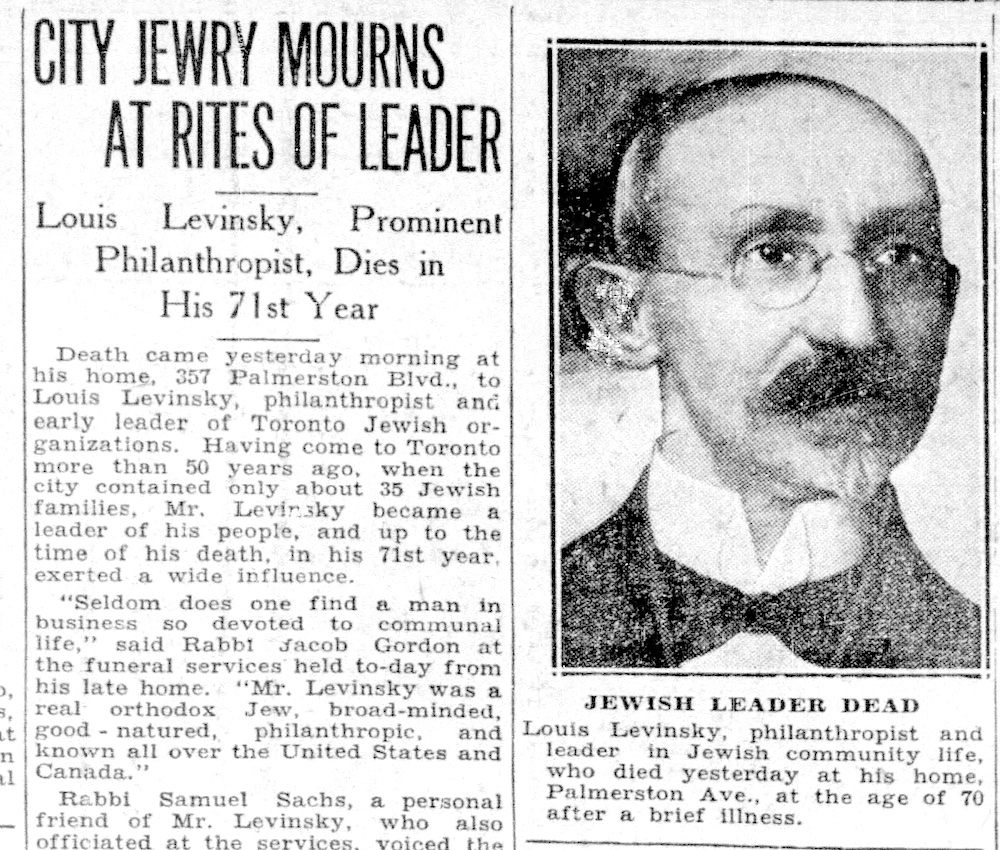

Richard Levinsky confirms that baby Alex and his mother returned to Toronto right away after his birth. Though There’s no entry for the child, the 1911 Canadian census shows Alex’s father, Abraham, and his mother, Dora, living in Toronto with Abe’s father, Louis Levinsky. The Levinsky family had been in Toronto for quite some time by then.

This is from the Toronto Star on January 4, 1932.

The 1901 Census shows that Louis Levinsky was from Russia, and came to Canada in 1881 (the 1911 Census says 1880), bringing over his wife (also named Dora) and eldest son Abraham in 1883. Later records indicate the family came from Poland, so Louis Levinsky was likely born in the western part of the Russian Empire, rather than Russia itself; perhaps in the area known as the Pale of Settlement. He came to Toronto at a time when the Jewish population was growing rapidly. (In 1871, 157 Jews lived in Toronto, rising to 1,425 by 1891 and 3,090 by 1901.) The community grew in the wake of immigration from Europe, where Jews suffered from persecution and pogroms.

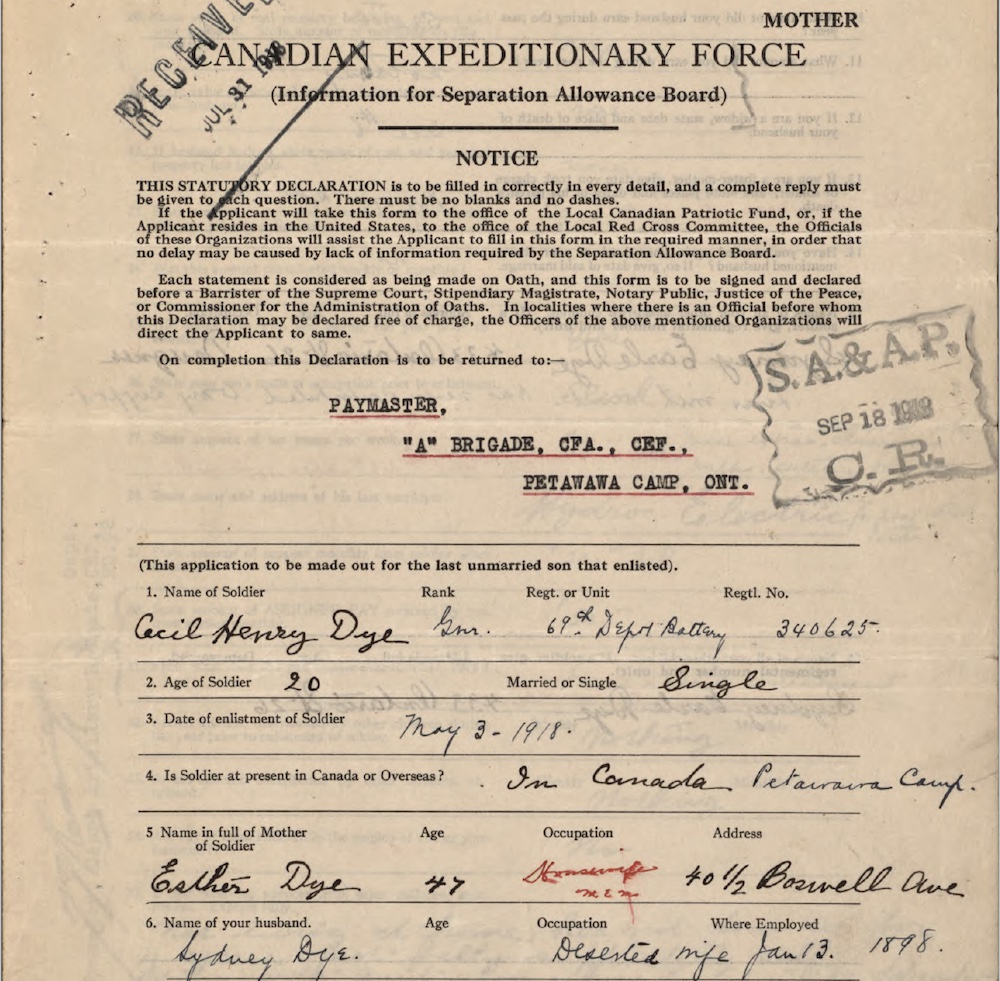

Differing records seem to show Alex’s father, Abe Levinsky, being born in 1881 or 1883. His World War I Attestation papers say 1892, but that must be wrong. Richard says his grandfather was born in Canada … and later Census records seem to confirm that. But even if he was born in Russia or Poland, Toronto was definitely home. And it appears Abe Levinsky was also an athlete. When he served in World War I, it was with the 180th (Sportsmen) Battalion of Toronto.

Alex Levinsky began to show his sporting prowess at a very young age. “When he wasn’t in school,” says Richard, “his mother would bring him lunch and dinner at the field or the rink.” By the time he was a teenager, Levinsky was earning city-wide recognition playing basketball and baseball for the Elizabeth Street playground team commonly known as the Lizzies. He was also a multi-sport star in high school at Harbord Collegiate.

The winter he turned 18 (1927–28), Levinsky played hockey for Moore Park, a top organization in the Toronto Hockey League, and helped the team reach the city finals in the juvenile division. A year later, he joined the powerhouse Toronto Marlboros, along with future Hockey Hall of Famers Charlie Conacher and Busher Jackson, who would soon be his teammates with the Maple Leafs. That April, the Marlboros won the Memorial Cup as Canada’s junior champions. Levinsky also played basketball for the Lizzies that winter, and in May, he led them to the Canadian junior championship as well. (In the fall of 1928, he’d led the Lizzies baseball team to the city finals, and in 1929 he would do the same with St. George’s. )

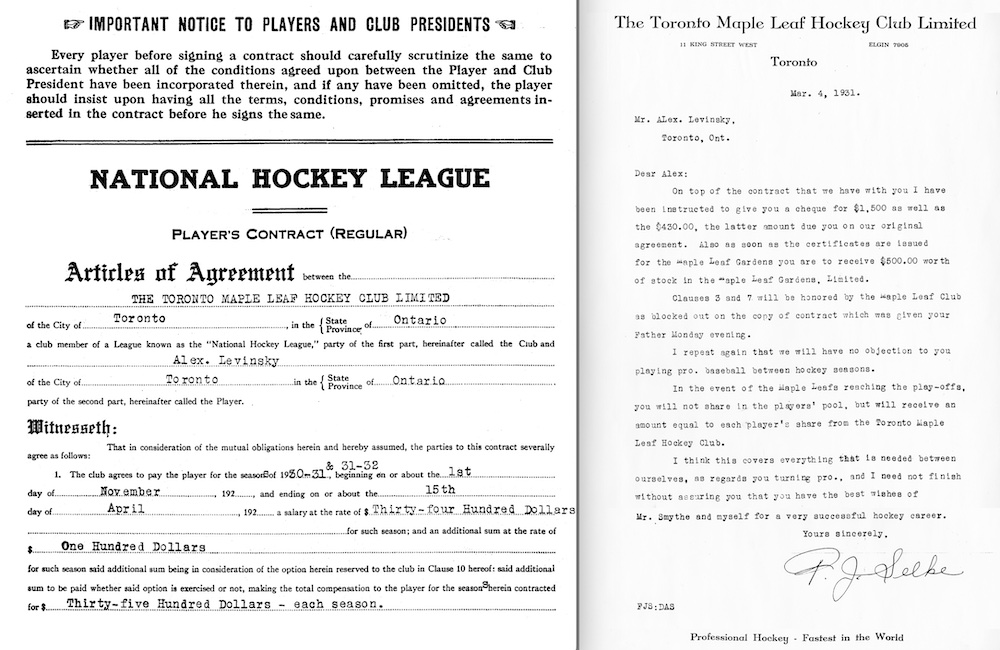

When Levinsky entered the University of Toronto in 1929, he played football in the fall and hockey in the winter. The Varsity junior hockey team reached the provincial semifinals of the Ontario Hockey Association, and when they were eliminated, Levinsky joined the senior team, who reached the provincial finals. While still a U of T student in 1930–31, Levinsky played senior hockey with the Marlboros. After they were eliminated from the OHA semifinals on February 28, 1931, he turned pro when he signed with the Maple Leafs on March 2. (NHL records currently show him and Marlboros teammate Bob Gracie playing their first games at home against the Canadiens on February 28, but local newspapers make no mention of that while reporting they would both play their first game for the Leafs in Philadelphia on March 3, 1931.)

At the time he turned pro, it had been expected that Levinsky would remain in school, having enrolled at Osgoode Hall to study law. Levinsky told Paul Patton (and Richard Levinsky confirms it) that Conn Smythe convinced him to go pro by arranging an off-ice job with the law firm of Plaxton, Sifton and Company. Hugh Plaxton had played for Smythe at the University of Toronto, and was a member of the Olympic gold medal-winning Varsity Grads of 1928. He was also Levinsky’s coach with the senior Marlboros. (A story in the Toronto Star on April 24, 1931, reports on Hugh Plaxton engaged as council for the plaintiff in a case with Levinsky as his assistant.) Levinsky never did finish school, nor practice law, but he would have a successful post-hockey career running several different businesses.

Frank Selke of the Maple Leafs. (Courtesy of Irv Osterer.)

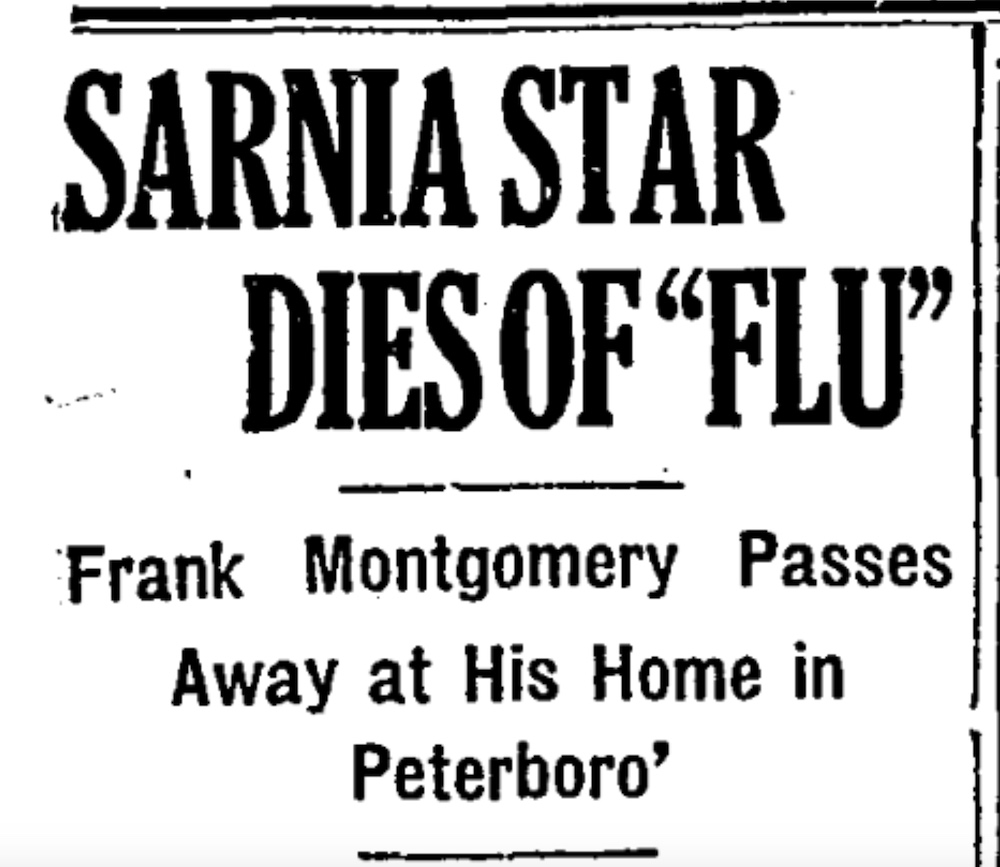

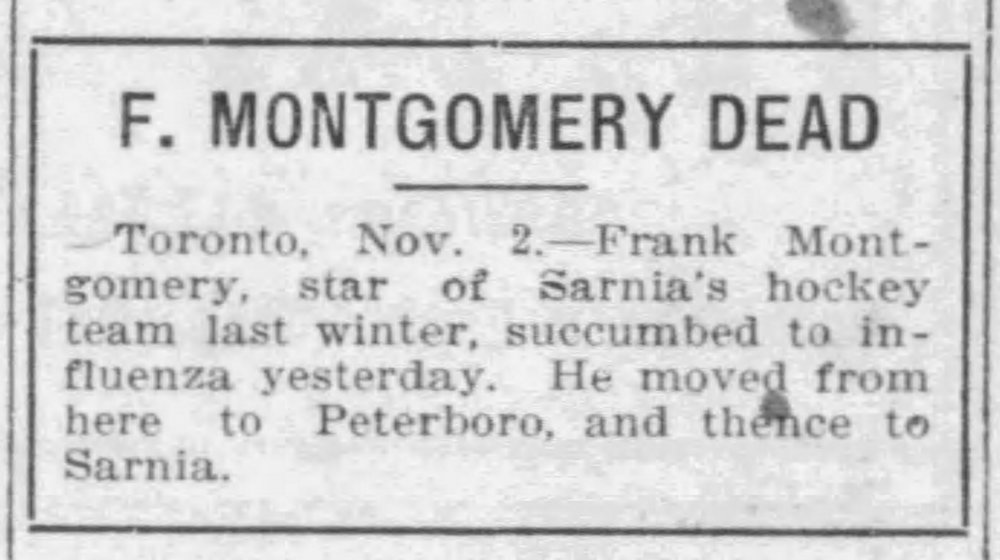

Meantime, in reporting on his upcoming home debut with the Maple Leafs against the Montreal Maroons, Lou Marsh of the Toronto Star wrote on March 4, 1931: “Levinsky’s appearance in a Leaf uniform here tomorrow should be good for at least three thousand new faces at pro games, his race is solidly clannish when it comes to sports.”

This is an example of the sort of casual racism Levinsky would often face throughout his career. Richard Levinsky says his father didn’t face a lot of anti-Semitism; at least not among teammates and fellow players. At 5’10” and with his weight listed over the years as being between 184 and 205 pounds, Levinsky was big … and he was tough.

According to Richard, when members of the Swastika Club attacked Jews in the summer of 1933 in the infamous Riot at Christie Pits — where his father had played plenty of baseball — Levinsky got a phone call and rushed to the park with a bat to help in the fight. Unlike Jackie Robinson, who was embraced in Montreal in 1946, Richard says his father faced his worst anti-Semitism in hockey when playing on the road in Montreal, where fans would scream “Jew!” at him in French the moment he got on the ice. But there’s also an interesting incident in Toronto from early in Levinsky’s first full season with the Maple Leafs in 1931–32.

Though the Leafs would go on to win the Stanley Cup in the spring of 1932, when the season opened at the brand new Maple Leaf Gardens in the fall of 1931, the team started poorly with three losses and two ties in their first five games. In a letter to the Sports Editor of the Toronto Star (now Lou Marsh, taking over from Foster’s father, W.A. Hewitt) on November 24, 1931, a fan writes:

Can Conny Smythe give the fans any reason why Alex Levinsky, who was the best defenseman that the Maple Leafs displayed in their first two games, has not been used since?… There was a lot of talk up at the Arena Saturday night that some of the Leaf players have stated openly that they will not play on the same team with a Jew, and that if Levinsky plays they will refuse to step out on the ice and for that reason Smythe rather than hurt the feelings of some of his pet hirelings intends railroading the big lad to one of the minor league teams…. There’s something rotten in Denmark and I think Conny Smythe owes the fans an explanation.

Richard Levinsky had never heard that story. There’s no actual proof any of the Leafs felt that way, and Alex Levinsky himself had a good relationship with the team owner. “Smythe stood behind his players 100 percent,” he told Dick Beddoes years later for a story in the Globe and Mail on October 28, 1966. “Big on loyalty, even — (he laughed to himself as he said it) — even to the point of naming race horses after us.” Conn Smythe called the Levinsky horse Mine Boy, which was Levinsky’s nickname.

(Image courtesy of Kevin Vautour.)

Interestingly, the earliest reference to the nickname I could find in newspapers is in the Owen Sound Sun Times on February 12, 1930. In a preview of game one of a series where the University of Toronto junior hockey team would eliminate the hometown Greys, the Sun Times notes: “Levinski [sp] is the lad to watch in this game. ‘Mine boy Alex’ as he is called by the Toronto fans, is a rushing back line man. And he has a shot!” Obviously, the nickname was already known in Toronto by then. The first reference to “Mine Boy” in the Toronto Star appears to come in a Lou Marsh report on a Marlboros game on January 8, 1931. It begins to appear regularly in Toronto papers very shortly after his Maple Leafs debut in March of 1931, and later stories mainly say it was Marsh who helped popularize it.

As the story goes, the nickname comes from the fact that Abe Levinsky would root for his son — his only child — by proudly shouting “That’s Mein Boy!” (‘mein’ or ‘meyn’ being the Yiddish word for ‘my’ … though technically מיין). Alex Levinsky in newspaper stories in 1934 said he preferred his nickname Mine Boy to any others, but there still may be some anti-Semitism behind it. Richard Levinsky says his grandfather was born in Canada and would have said “My boy,” not “Mein boy.” So, if it was Lou Marsh playing it up, he was likely playing to common stereotypes at the time. (There are certainly plenty of racist tropes in much of Marsh’s writing, which is why the name of the Lou Marsh Trophy, first awarded to Canada’s best athlete after Marsh’s death in 1936, was changed to the Northern Star Award in 2022.)

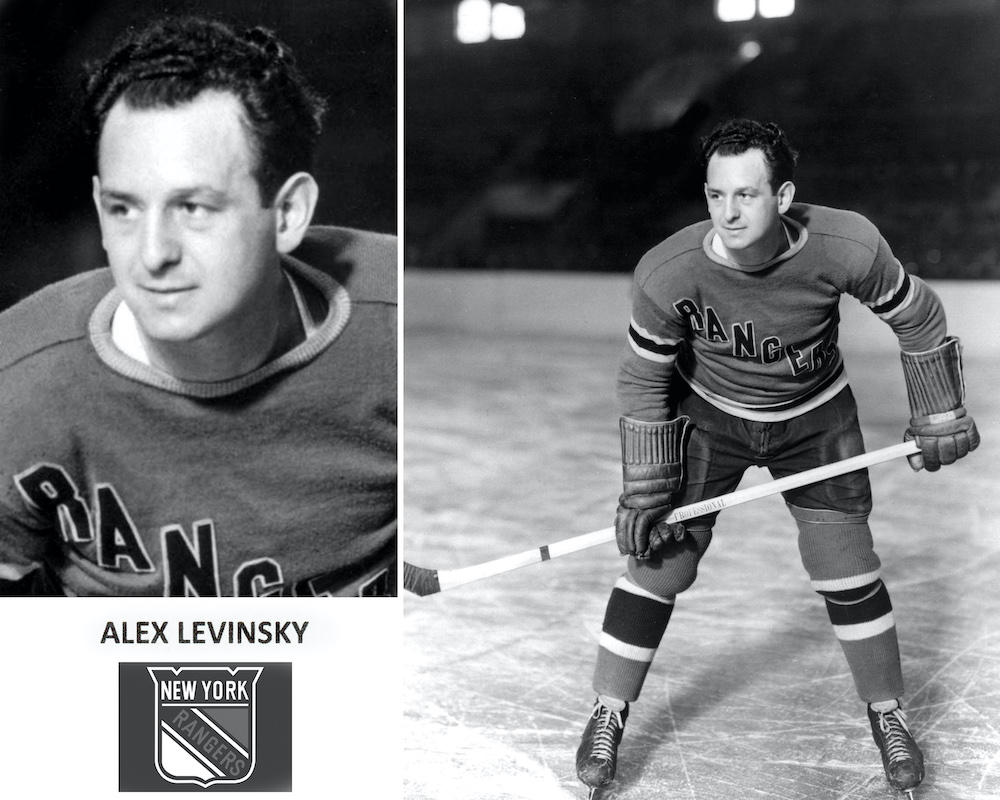

“Mine Boy” Levinsky was one of four Maple Leafs defensemen during his time in Toronto along with future Hall of Famers King Clancy, Hap Day, and Red Horner. He helped the Leafs win the Stanley Cup over the New York Rangers in the spring of 1932, and reach the finals again when they were beaten by the Rangers in 1933. But ever since Levinsky had entered the NHL, there had been talk of what a success he would be in New York, where the Rangers so longed for a Jewish star they had tried to pass off goalie Lorne Chabot as Lorne Chabotsky. (Original NHL game sheets from the 1926–27 season occasionally list the names Shabatsky and Schavatsky for Chabot; Ollie Reinikka was sometimes listed as Rocco to appeal to Italian New Yorkers.) So, when the Leafs found themselves short of cash after the 1933–34 season, they had a pretty good idea how to come up with it. Frank Selke told the story to Milt Dunnell of the Toronto Star on October 12, 1981:

Because we had been unable to sell as much stock [when building Maple Leaf Gardens] as we expected due to The Depression, there was a threat that the insurance company which held our mortgage might take over the building. Part of our agreement was that we must have at least $40,000 in our bank account at all times. At one stage, our cash on hand got so low that we had do do something quickly. I went down to New York and explained our situation to Lester Patrick (general manager of the Rangers). Lester bought Alex Levinsky from us for $12,000.

But Levinsky barely lasted half a season in New York. Richard says his father didn’t get along well with the coach … also Lester Patrick. There are certainly several newspaper articles in which Patrick is critical of Levinsky and future Hall of Fame defenseman Earl Seibert before Levinsky is sold to Chicago on January 16, 1935, where he would replace Taffy Abel.

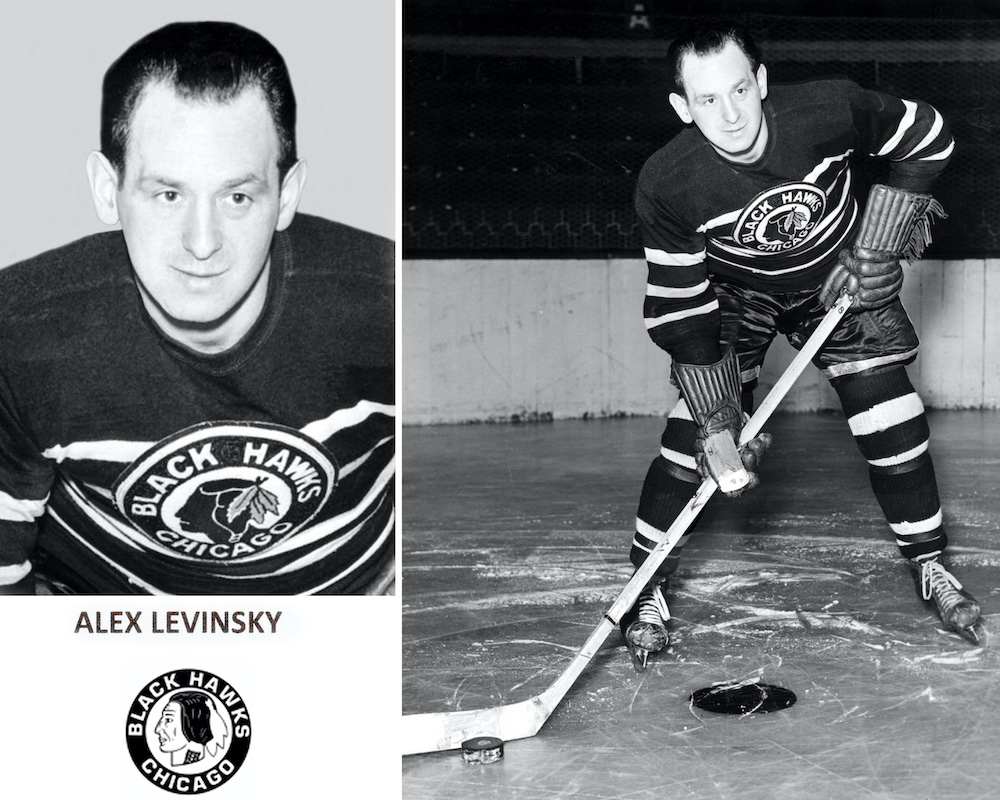

Alex Levinsky spent four years in Chicago, helping the Black Hawks win the Stanley Cup in 1938 by defeating the Maple Leafs. But midway through the 1938–39 season, he was traded to the Rangers’ Philadelphia Ramblers farm team. Richard Levinsky remembers a very interesting story about that.

Richard recalls his father saying that when he was playing in Chicago, he became a favourite of Jewish gangsters Meyer Lansky and Bugsy Seigel. When the Black Hawks traded him to Philadelphia, the men asked Levinsky if he’d like them “to take the coach for a ride.” Richard was never sure he believed the story, until he saw it confirmed in a book. But the only reference I could find tells the story somewhat differently. In the book But He was Good to His Mother about the lives and crimes of Jewish gangsters, author Robert Rockaway writes of an unnamed group of Jewish mobsters offering to protect Levinsky on and off the ice after a particularly blatant anti-Semitic outburst.

Whichever version of the story is the real one, in both tellings, Alex Levinsky turned them down.