The World Series starts tonight. It’s the most classic of Fall Classic match-ups, with the Yankees against the Dodgers. This will mark the 12th time the two teams have met for all the marbles. I’m sure baseball is thrilled to have the two biggest markets going head-to-head with some of the biggest stars in the game on the biggest stage, led by probable League MVPs Shohei Ohtani of the Dodgers and Aaron Judge of the Yankees.

Now, there’s pretty much no team in sports I’ve ever disliked as much as the New York Yankees. As long-ago comedian Joe. E Lewis once said, “Rooting for the Yankees is like rooting for U.S. Steel.” My mother – really, the reason our family is baseball crazy — grew up a fan of the Brooklyn Dodgers, but the Los Angeles Dodgers have never been the lovable “Bums” of their Brooklyn days. Rooting for them is like rooting for Amazon. So, I don’t think I’ll know who I want to win until I’m watching and I see how I feel as the Series progresses.

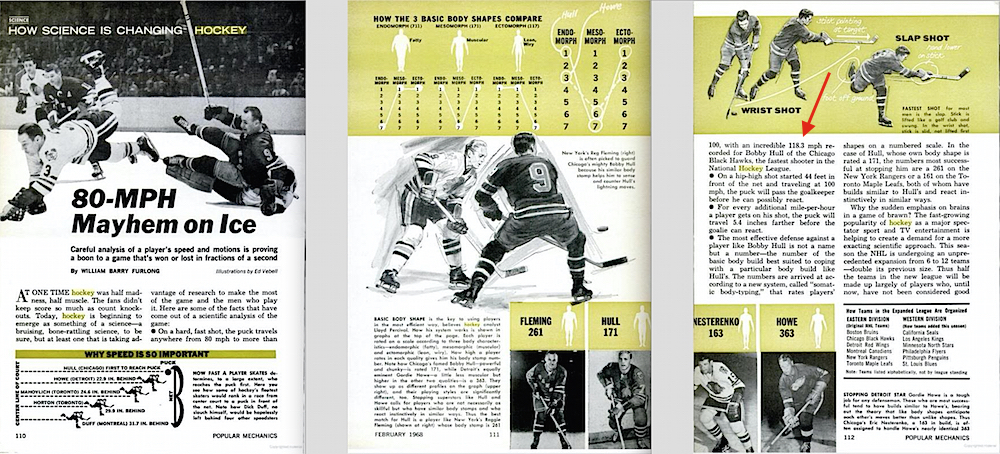

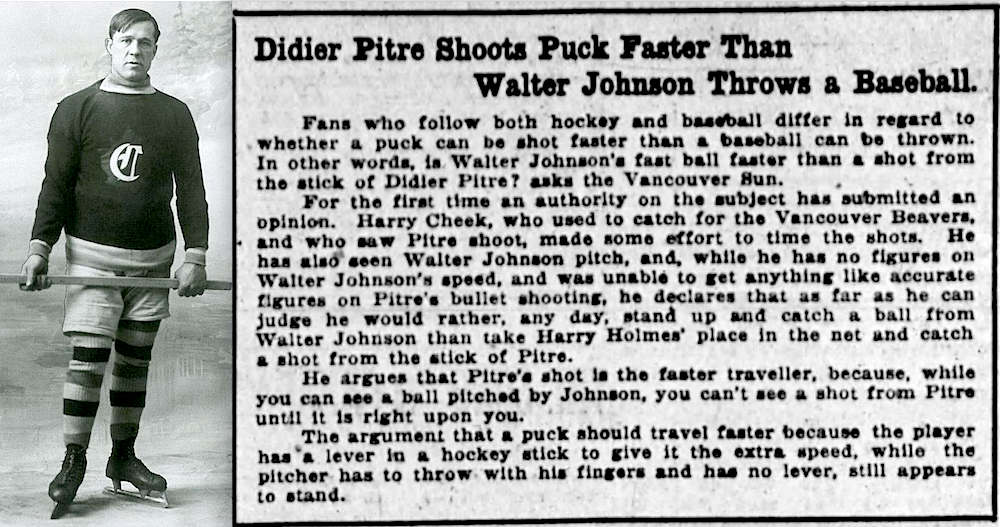

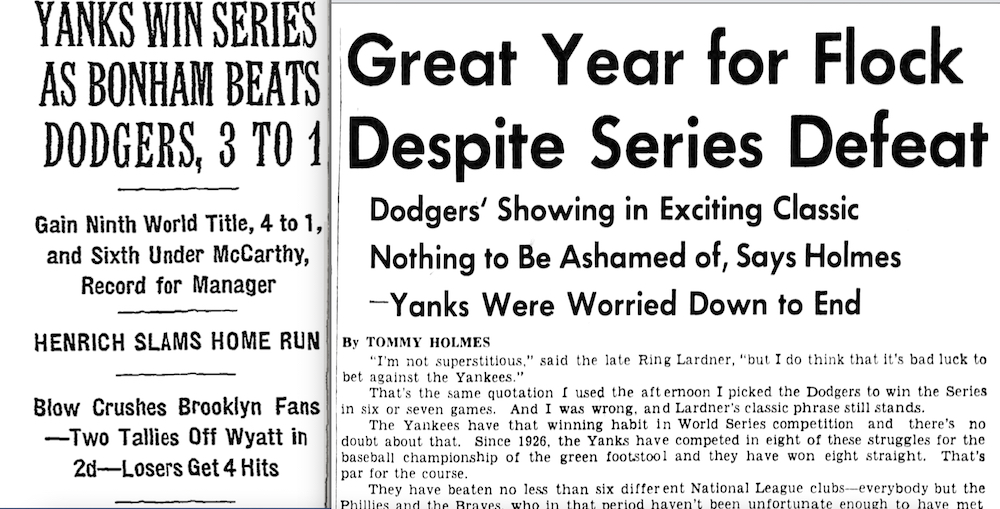

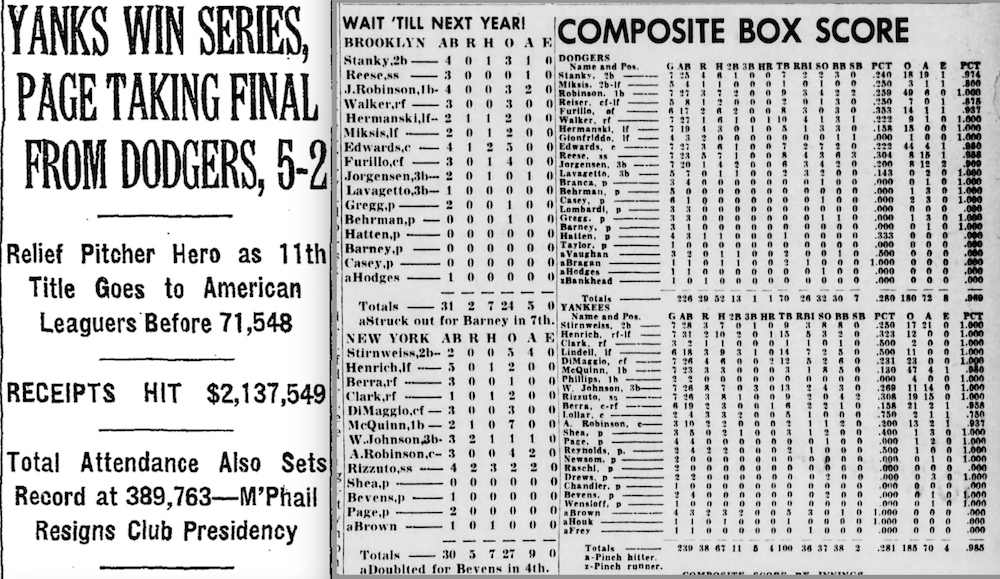

Below is a history of the 11 previous Yankees-Dodgers World Series in newspaper pages. I’ve “borrowed” from the The New York Times, the Brooklyn Eagle, the Brooklyn Caravan, the Brooklyn Daily, The Los Angeles Times, and Newsday. (New York stories are on the left; Brooklyn/Los Angeles stories on the right.)

The Yankees beat Brooklyn 4 games to 1 in the 1941 World Series. The turning point in the Series came when Dodgers catcher Mickey Owen dropped the third strike that would have ended Game 4 with a Brooklyn victory but instead allowed the Yankees to rally for a victory.

The Dodgers integrated baseball in 1947 with Jackie Robinson on their roster. The World Series featured a near no-hitter by the Yankees’ Bill Bevens in what turned out to be a losing effort in Game 4 and an Al Gionfriddo catch that robbed Joe DiMaggio of extra bases in Game 6. Still, the Yankees beat the Dodgers in 7 games. (Note WAIT ‘TILL NEXT YEAR! in the Brooklyn Eagle.)

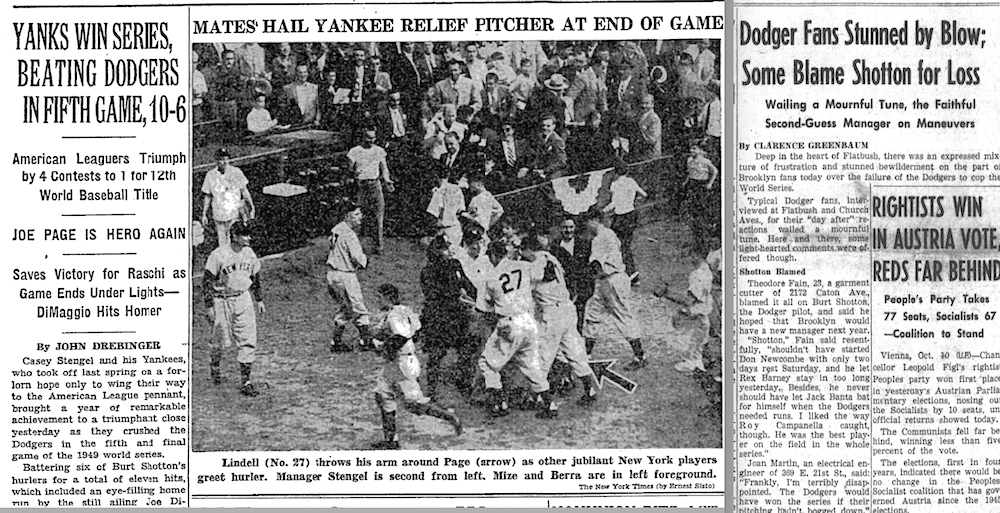

Both teams were 97–57 in 1949, but the Yankees won the World Series in 5 games. It would be the first of record five straight Yankees championships.

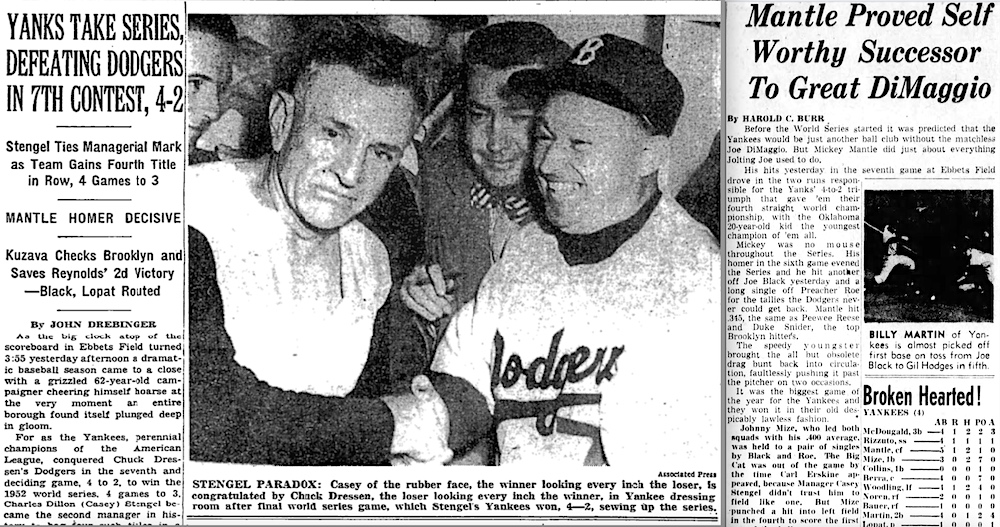

The Yankees won the 1952 World Series in seven games, with second baseman and future manager Billy Martin making a game-saving catch to preserve a 4–2 victory in Game 7.

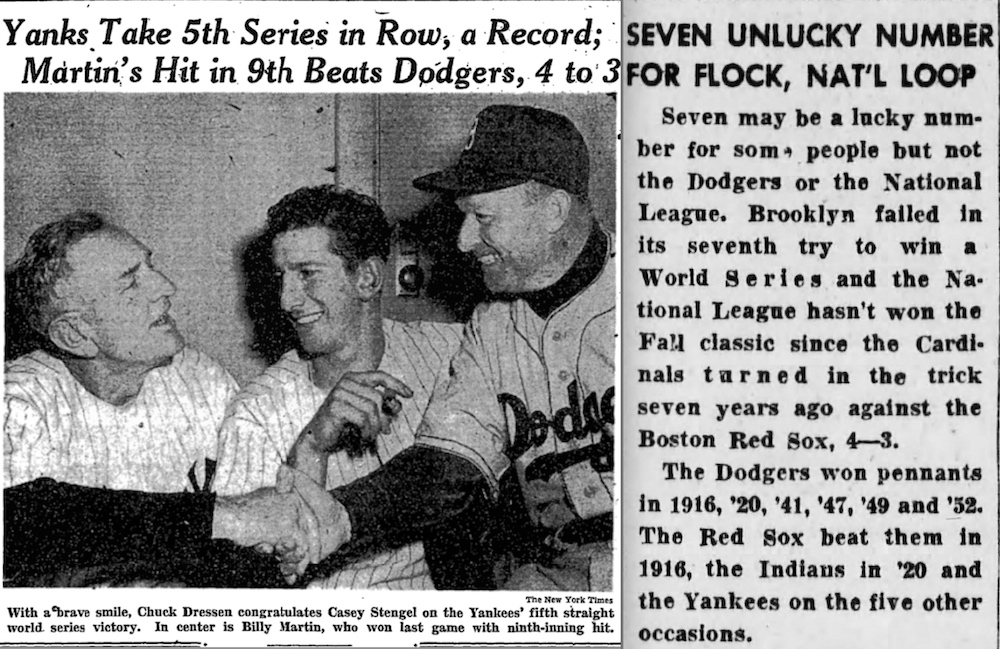

Five in a row, and two straight over Brooklyn, for the Yankees in 1953. Billy Martin was the hero again, hitting .500 with a record-tying 12 hits and a walk-off RBI single in the Game 6 finale.

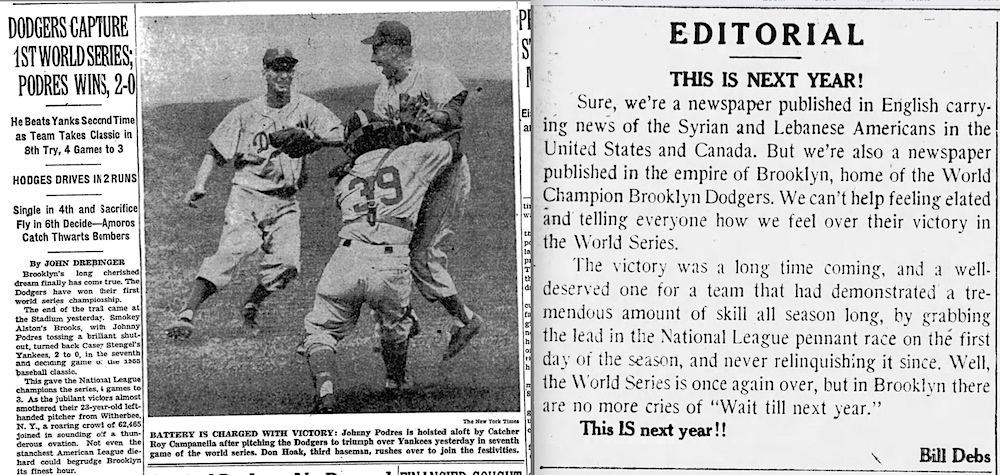

Next Year finally arrived in Brooklyn in 1955 after seven straight World Series losses and four in a row to the Yankees. Dodgers Pitcher Johnny Podres was just 9–10 on the season, but threw a complete game victory on his 23rd birthday in Game 3 and a 2–0 shutout in Game 7 to win the first World Series MVP Award.

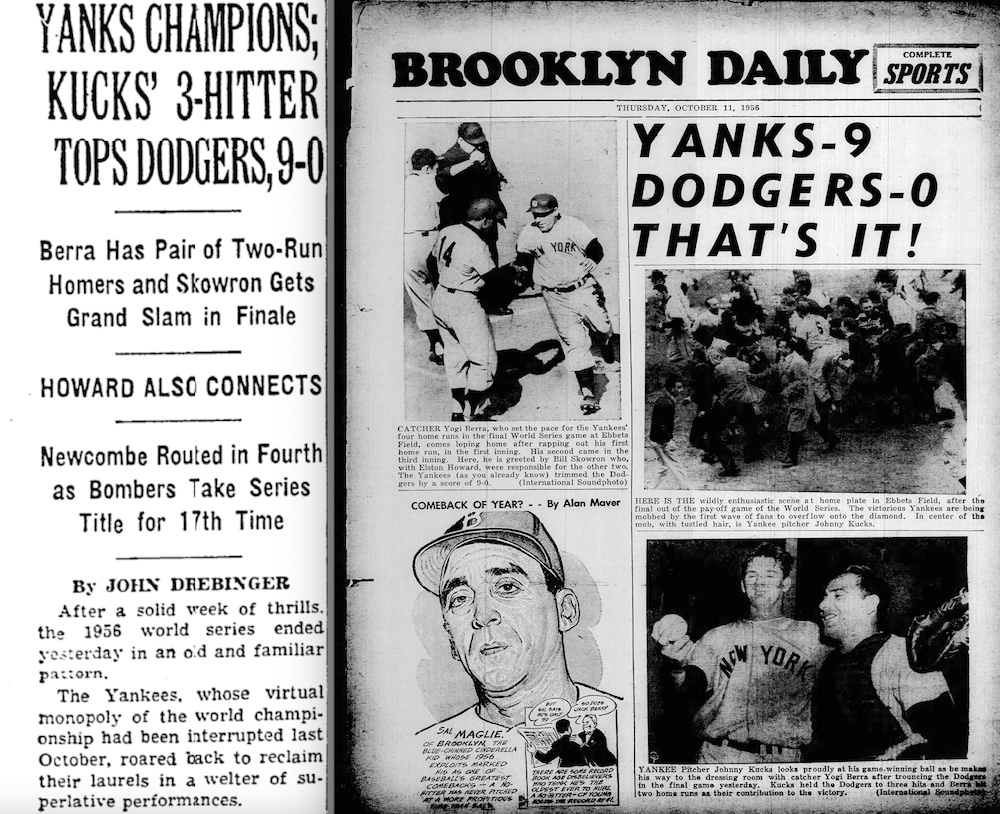

The Yankees were back on top in 1956 with a blowout 9–0 victory in Game 7. The 1956 World Series is best remembered for Don Laren’s perfect game for the Yankees in Game 5. After the 1957 season, the Dodgers would move to Los Angeles (and the Giants to San Francisco) for 1958.

For the first time in team history, the Yankees were swept in the World Series. They never even had a lead! Dodgers pitchers Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale, Johnny Podres, and ace reliever Ron Perranoski combined to give up only four runs in four games. Koufax threw complete games in Games 1 and 4 to win World Series MVP.

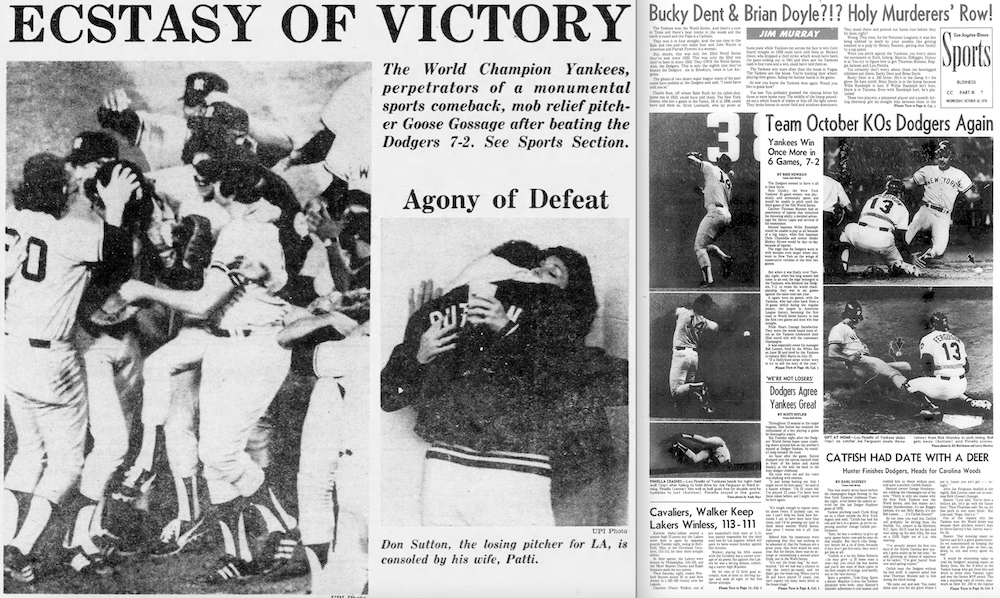

The Yankees hadn’t won the World Series since 1962 (they’d lost in 1963, 1964, and 1976) when they returned to their winning ways in 1977. A six-game victory of the Dodgers was punctuated by three home runs on three consecutive swings by World Series MVP Reggie Jackson in an 8–4 victory in Game 6.

After losing the first two games in Los Angeles, the Yankees won three straight back in New York and then wrapped up the series back at Dodgers Stadium with a 7–2 win in Game 6. Bucky Dent, who homered in a tie-breaker game against the Boston Red Sox at Fenway Park at the end of the 1978 regular season, hit .417 in the World Series with seven RBIs to win MVP.

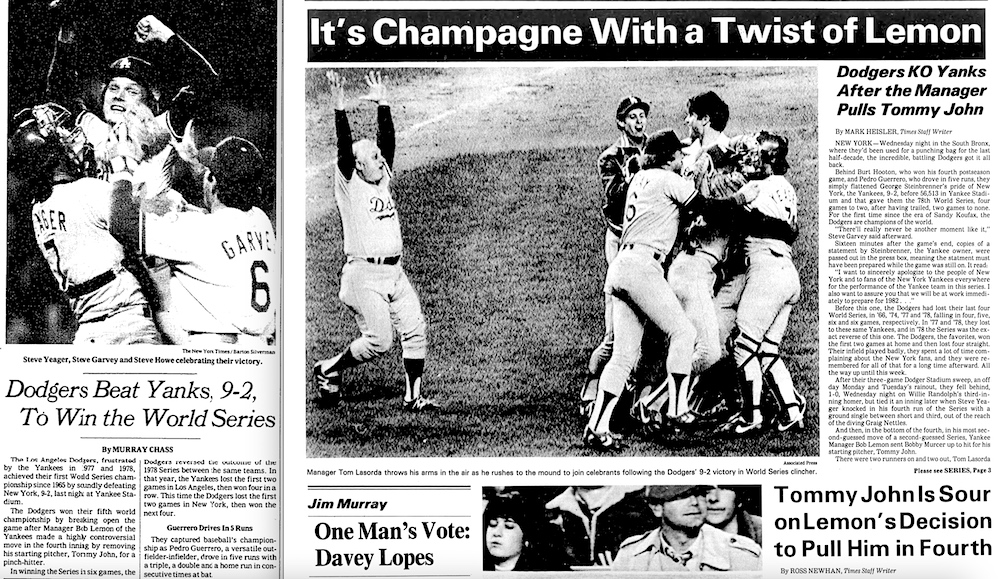

After a strike-torn “split” season in 1981, the Dodgers beat the Yankees to win the World Series. In a reverse of 1978, the Dodgers dropped the first two games in New York, returned home to win three in a row, then won Game 6 at Yankee Stadium. Ron Cey, Pedro Guerrero, and Steve Yeager of the Dodgers shared the MVP award.

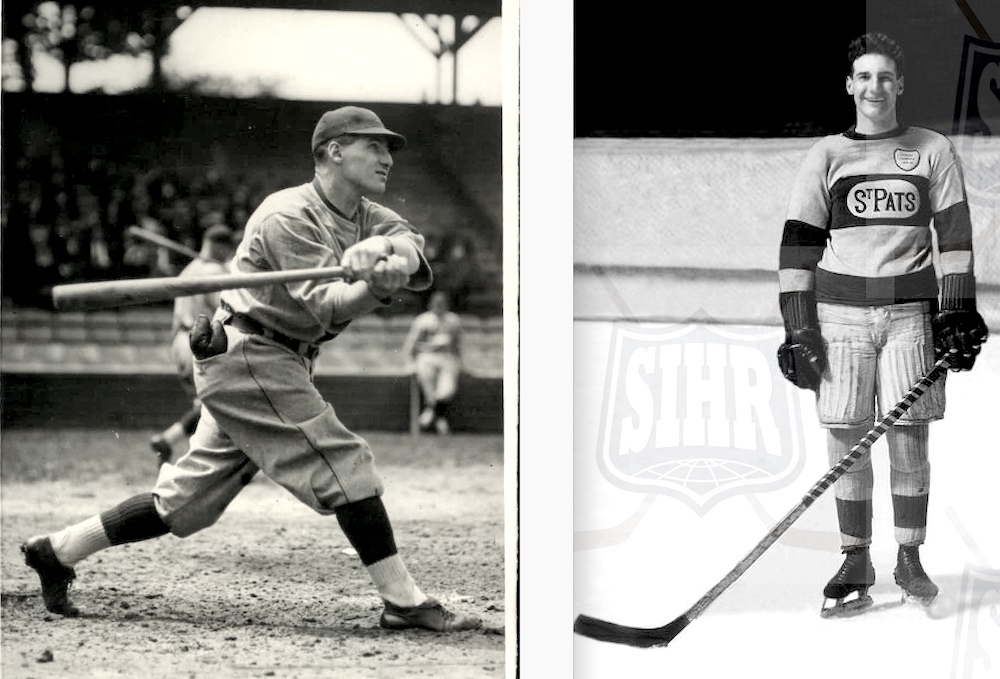

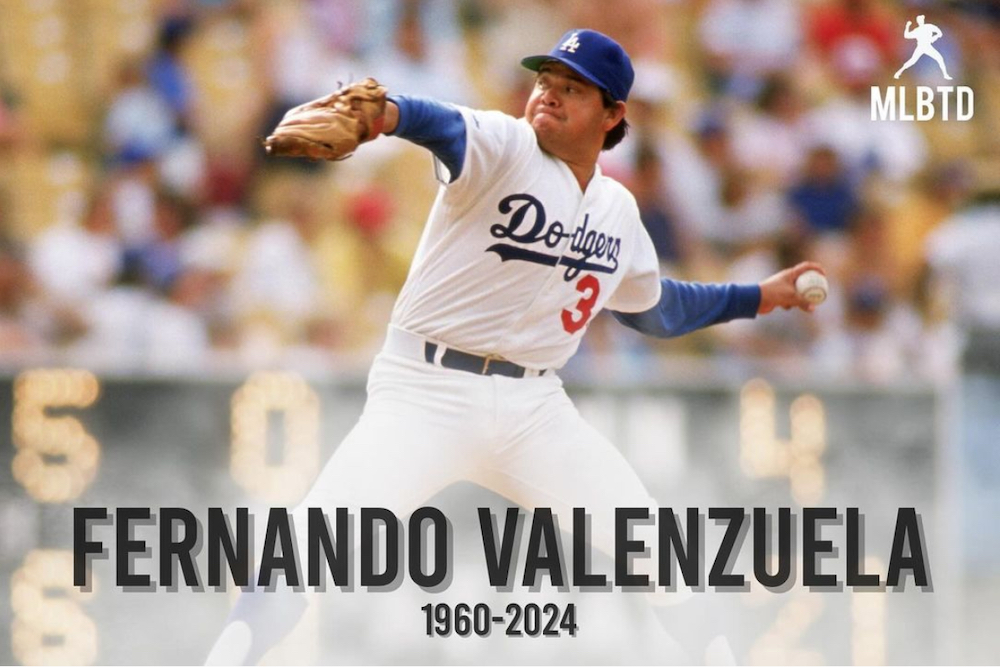

A key member of the Dodgers’ 1981 World Champions was pitcher Fernando Valenzuela, who passed on Tuesday. He had recently taken a leave of absence from the Dodgers’ Spanish-language broadcasts, but while he had been sick for quite a while with liver cancer, he told almost no one about his illness in order to preserve his privacy.

Though he’d appeared as a reliever in 10 games in 1980 (with two wins and a save), Valenzuela truly burst onto the scene as a starter in 1981. A late replacement for Jerry Reuss on Opening Day, Valenzuela pitched a complete game five-hit shutout in a 2–0 win over the Houston Astros. It was the start of an amazing run that launched “Fernando-mania.”

In his first eight stars of 1981, Valenzuela threw eight straight complete games and won them all, allowing just four runs while throwing five shutouts. A lefty with a unique delivery and a devastating screwball, he is still the only pitcher to win the Cy Young Award and the Rookie of the Year in the same season.

A nagging shoulder injury would slow him down after a career-high 21 wins in 1986, but Valenzuela remained with the Dodgers through the 1990 season. He later pitched for the Angels, Orioles, Phillies, Padres, and Cardinals before retiring in 1997. His career record was 173–153 with an ERA of 3.54 and a no-hitter he pitched in 1990.

The Dodgers retired Valenzuela’s #34 in the summer of 2023. He will be honoured during this year’s World Series, and the Dodgers will wear a commemorative patch during the Series and throughout next season.