I’m sure I’ll get into the World Cup of Hockey when it starts up for real in a few days. But September is for baseball and pennant races! Of course I wish that the Blue Jays were doing better than 3-and-8 this month, but I’m trying to remember that for years (decades!) before last season, all I wanted was meaningful games in September. And, well, we’ve certainly got that now.

I was at the Blue Jays-Red Sox game on Saturday (the good one, that we won 3-2) with my two brothers and my nephew. Jorey is 13 now, and pretty much exactly like his father and uncles were at that age. At one point during the game, he wondered if any of us knew who was likely to be the next player to reach 3,000 career hits early next season. We didn’t.

Once upon a time, I’m sure I would have known that immediately. These days, of course, I could look it up with a few taps and swipes on my phone (which I’ve since done – though on my laptop). It’s funny how, now that it’s so easy to know this stuff if you want to, I don’t know it anymore. Back in the old days, when I had to study the all-time lists in the annual preseason Street & Smith’s Baseball Magazine and then, basically, keep it in my head all season, I pretty much did. Now I don’t.

So, any idea who, as of last night’s game, got his 2,926th hit (and 443 home run, by the way)? I’ll put the answer in at the bottom of this story … and I’ll be curious to hear from anybody who can tell me they honestly knew it without looking it up!

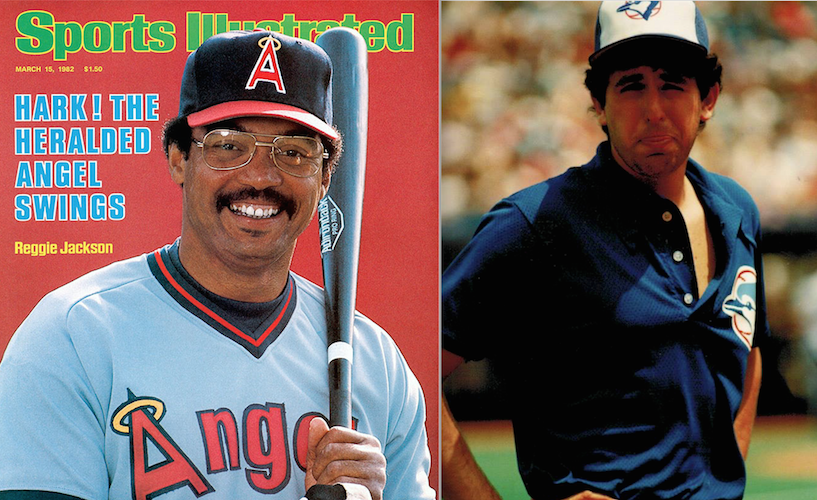

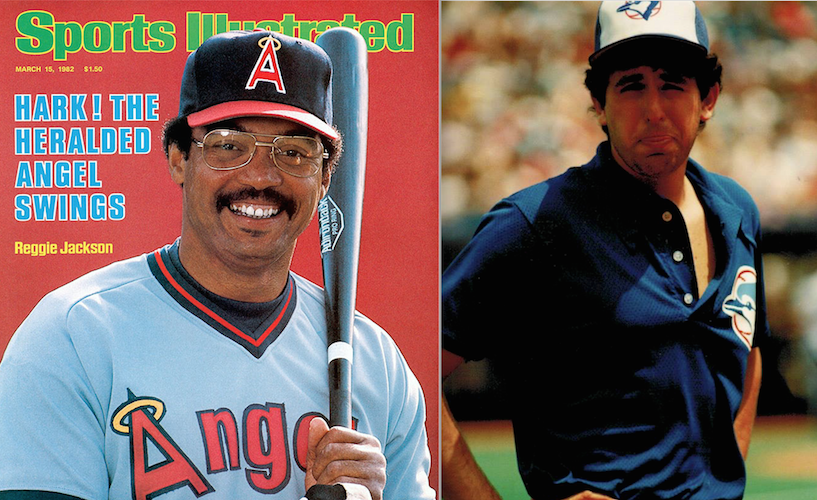

Jorey also asked us who, in 40 seasons as Blue Jays fans, is the greatest player we’ve ever seen. We threw out a lot of names, and then finally decided it was probably Ken Griffey Jr. But good as he was, Griffey never really won anything. So I was wondering if, maybe, given all he did on the largest stage, the greatest player was Reggie Jackson. All those “Mr. October” moments definitely made an impression on me when I was Jorey’s age.

That being said, I never liked Reggie Jackson. (I know I’m not alone there.) He was just too pompous and arrogant. But I do have one good Reggie Jackson story from my days on the Blue Jays ground crew.

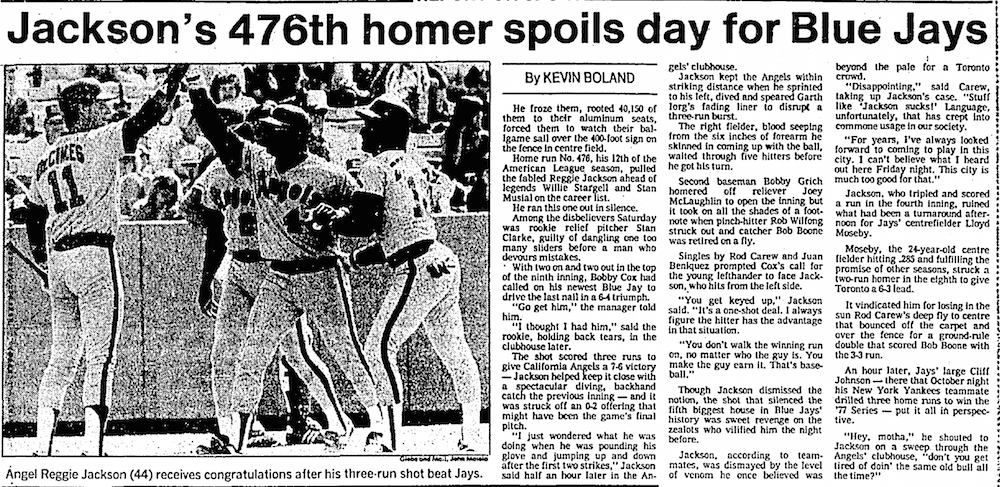

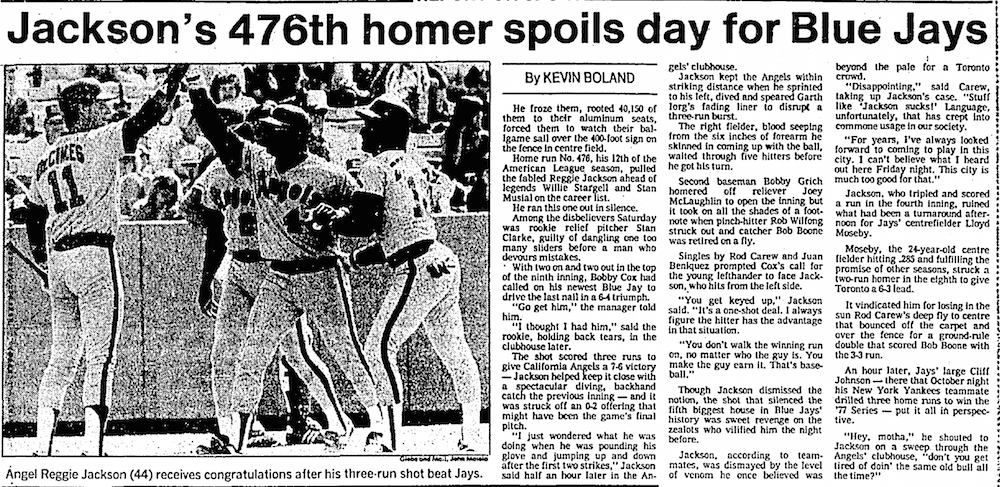

During the early summer of 1983, when the Jays were first becoming contenders, the California Angels were in town. On this Saturday (June 18), Jim Clancy had pitched seven strong innings but surrendered our tight, 3-2 lead when he gave up back-to-back doubles leading off the top of the eighth. Joey McLaughlin came in, put a couple more guys on, but got out of trouble. The Jays then took back the lead with three runs in the bottom of the eighth, highlighted by a two-run home run from Lloyd Moseby.

But the Angels weren’t done. Bobby Grich led off the ninth with a homer and then, with two out, Rod Carew and Juan Beniquez singled, bringing Reggie Jackson to the plate. Bobby Cox went to the bullpen for a lefty – rookie Stan Clarke, who’d made his Major League debut just 11 days before. Clarke quickly jumped ahead 0-2.

“I wanted that situation bad,” Clarke told reporters after the game. “I wanted to strike him out. That’s all I wanted to do.”

In my memory, you could literally see Clarke shaking with the excitement of it. Almost laughing that he’d actually gotten Reggie Jackson to foul off a couple of pitches and was going to strike him out and save the game.

“I stepped back off the mound, and I told myself: ‘Relax and throw your best pitch.’ But it didn’t work out that way.”

Reggie slugged the next pitch for a three-run homer, and glared at Clarke as he rounded the bases. He’d seen the young lefty shaking too.

“I just wondered what he was doing when he was pounding his glove and jumping up and down after the first two strikes,” said Reggie after the game.

There was still the bottom of the ninth to come, but you just knew it was over. “The Blue Jays had no chance to recover,” wrote Allison Gordon in The Toronto Star. “It wasn’t meant to be.”

Now it was me who was practically shaking, but with anger. Anybody who knows me (and especially those who knew me then) will have no trouble envisioning me stomping around flailing my arms, muttering, “Stupid Reggie! Stupid Blue Jays! Stupid Game! How Could They Blow It!” Which is what I was doing when I fell down the steep flight of stairs that was practically a ladder after taking down the flags from atop the press box a short time later. (I threw down the flags as I was slipping and managed to grab onto the railing and break my fall.)

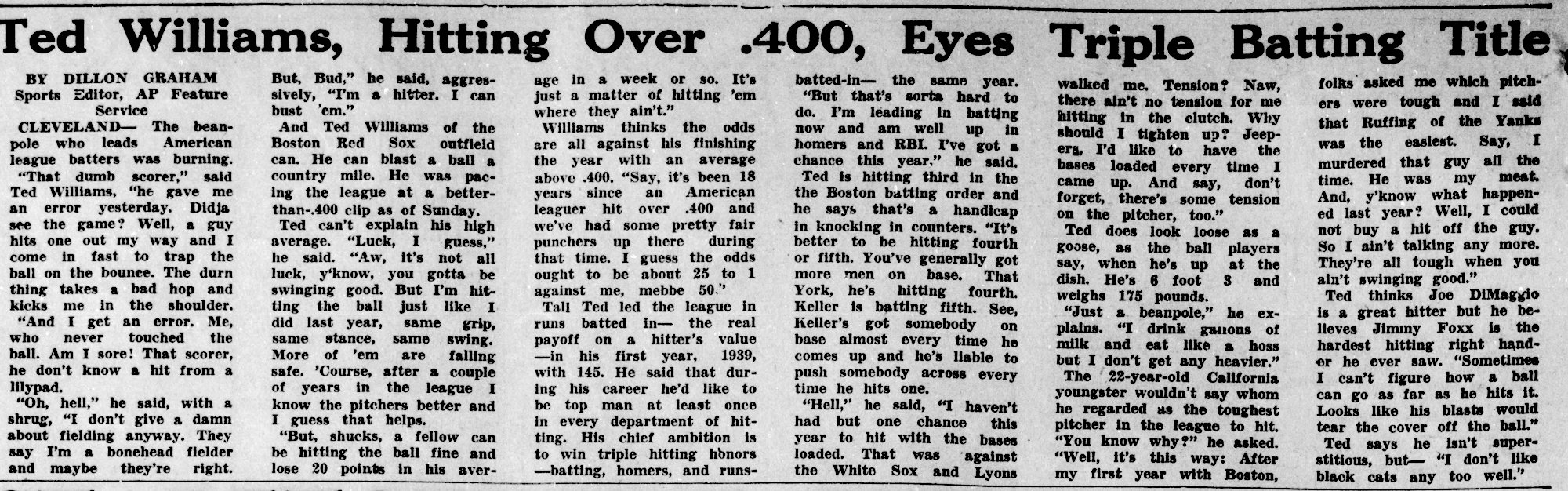

Getting back to what is sort of the point of this story, because I knew all the stats in those days, I knew that Reggie’s 476th career homer moved him past Stan Musial and Willie Stargell on the all-time list. So, the next day, when I happened to find myself standing beside the cage before the game while Reggie was awaiting his turn for batting practice, I said to him, “Congratulations on passing Stan and Willie, but I’m sure you understand why I’m mad at you.”

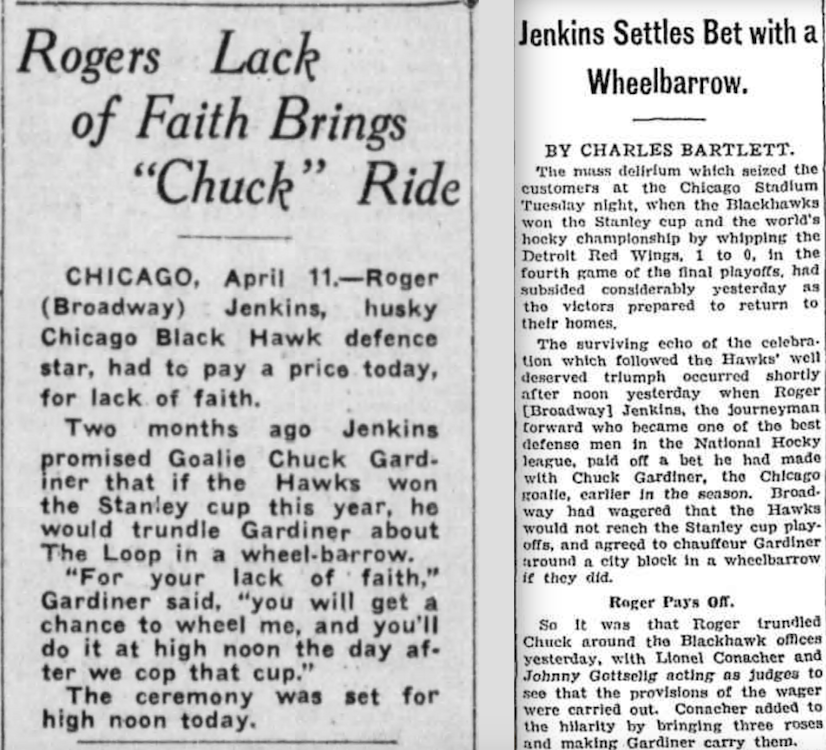

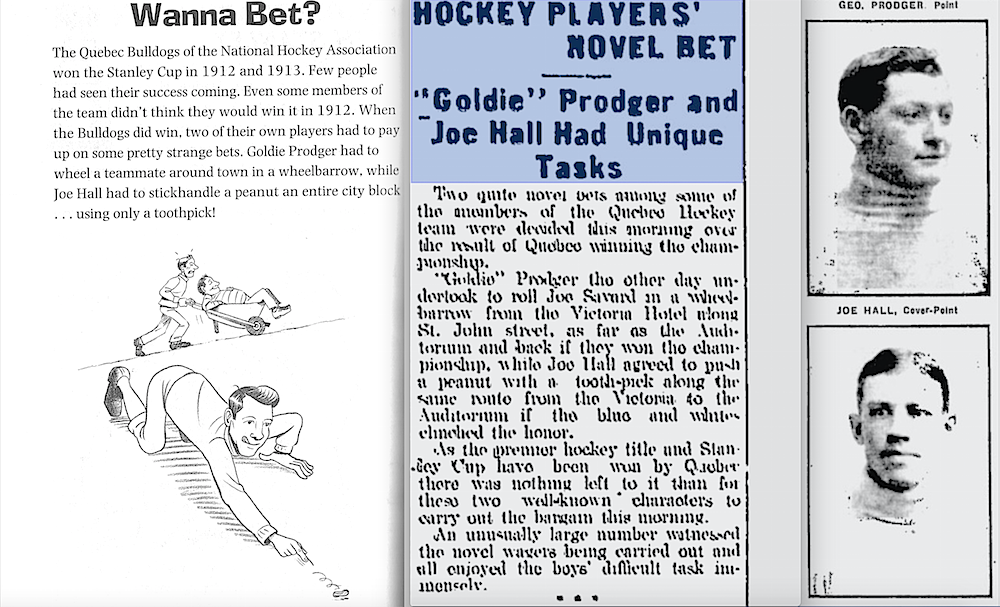

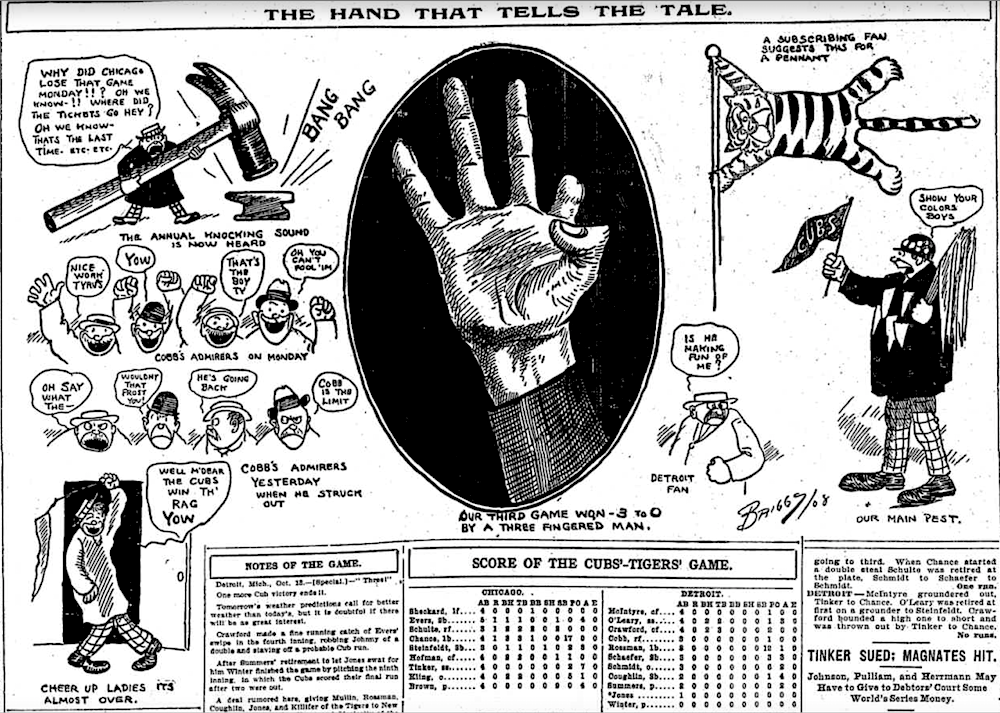

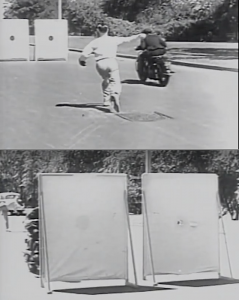

I was up there near the lower part of the red square when I fell …

but I would only have fallen as far as the bottom red line.

He didn’t say anything. Just nodded and smiled a self-satisfied smile. Stupid Reggie!

Oh, and the answer to Jorey’s question: It’s Adrian Beltre.