Last month, I received an email from Don Weekes. (For those of you who don’t know, Don is a fellow hockey historian/author who has written several books of hockey trivia and hockey firsts, as well as Picturing the Game: An Illustrated Story of Hockey, which was — for my money — the best hockey book of 2023.)

In his email, Don asked: Have you done or seen any (solid) research on Fred Waghorne and the face-off? Is he really the guy who started the puck drop? I guess it would be nice if it’s mentioned somehow in an old game report from 1900. Have you ever run across anything to prove what has appeared any number of times in books?

In my own work, I often ask questions of my fellow writers/researchers, or experts in the field, or to the editors I’m working with. Whenever I do, I want an answer NOW! So, when people ask me, I try to respond as quickly as possible As soon as I received Don’s email, I gave him a call. We mostly talked about other writing-related things, so that after he received another call he had to take, I ended up texting him my answer:

Regarding Fred Waghorne, no, I’ve never seen any direct proof about the puck drop.

A longtime referee in both hockey and lacrosse, if you Google the name Fred Waghorne, you’ll come across lots of stories about him being the first referee to drop the puck for a face-off. (Also about whether he pioneered the use of whistles among hockey referees, or the old-time practice of using a cowbell instead.) Many of the face-off stories are very similar, though all are pretty vague. Even when they give places and teams, there’s never been any specific date attached. Not even a reliable year. Still, later that afternoon, I went searching for more. Having done this before, I didn’t really expect to find anything … but there are so many old newspapers available online that there didn’t used to bet so it seemed worth a try.

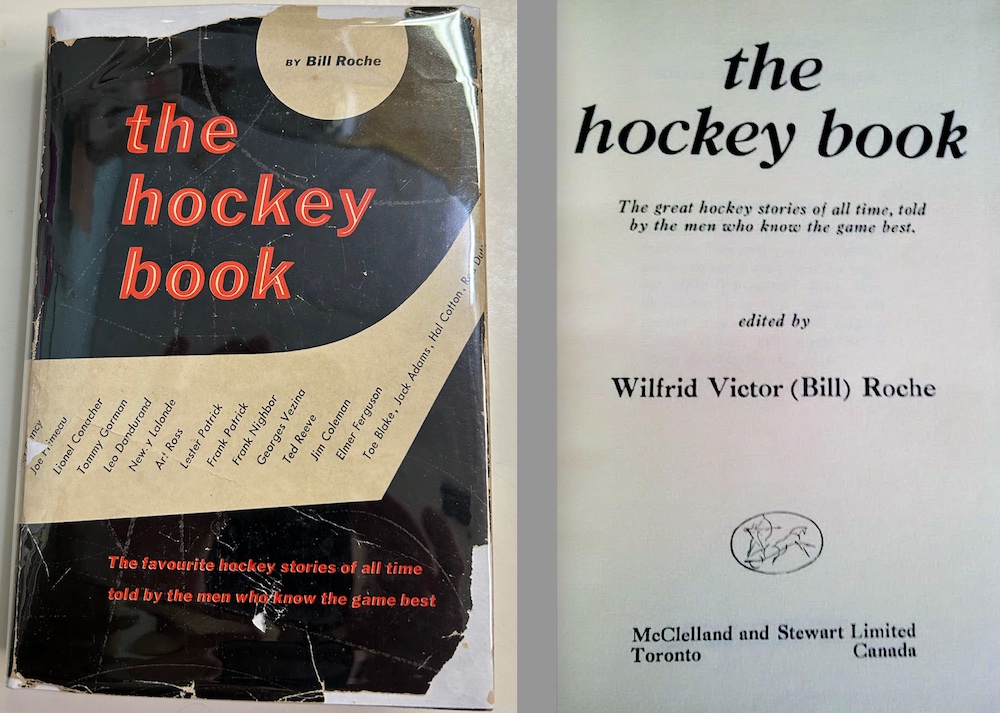

At first, I didn’t find anything. Then I found a story in the Windsor Star from December 19, 1953. It was actually about The Hockey Book, by Bill Roche, which had come out that year. “It is a collection of hockey stories and anecdotes,” the article explains, “by the game’s great personalities — Cyclone Taylor, Art Ross, Newsy Lalonde, and many more who are legendary already… One of the first referees is here, too — Fred C. Waghorne, who changed face-off and other rules.”

Nothing new there … but I have a copy of The Hockey Book. (Art Ross’s copy, in fact, given to him by Bruins chief scout Harold “Baldy” Cotton, and given to me by Ross’s grandson, Art Ross III.) I suppose I must have read Waghorne’s stories before, but now I had reason to read them again. Though he was 88-years-old by then, and it was some 50 years after the fact, here’s what Waghorne had to say about face-offs:

When young fans see hockey played these days, the face-off that starts play must seem to be a simple, obvious thing. The referee just tosses the puck between a pair of sticks and the game is on. But it wasn’t always done that way. There were years of exasperating and often painful experiences for referees before the present style of face-off was instituted. I know, because I’m the referee who brought it about.

First, I should point out that it was not “invented” by any great wave of mental brilliance on my part. I was really just acting in self-defence and trying something that would speed up the game.

Face-offs in the early days of hockey were similar to what they still are in lacrosse. The referee would place the puck on the ice between the blades of the centers’ sticks, lean over the puck to line up the sticks fairly, step back, and shout, “Play!” But, as Waghorne explains, things seldom worked out that way.

Just after the referee had placed puck and sticks, and before he had time to move out of range, one centreman would feel the other fellow’s stick wiggling a bit, and he’d try to beat the other boy to the draw. Both would start to slash and swipe at the puck. And before the referee could move away, he’d often get banged by a stick on a shin or toe. Also, every time the centremen started chopping away before the official had a chance to give the signal, the puck had to be faced-off again. This held up play so often that it got to be monotonous.

Waghorne explains that around the year 1900, he refereed a game in Southwestern Ontario. He could no longer remember the place, “but it was in the Brantford-Paris-Woodstock area.” The rival centers were definitely cheating on the draw that night, and Waghorne was tired of it.

I said to myself, “To heck with the rules in this case!” Then I told the centremen what I was going to do. They were to place their blades on the ice about a foot and a half apart and I’d stand back and toss the puck between their sticks. After the rubber hit the ice, they could do as they darned well pleased.

Waghorne says his face-off experiment worked out well, and that he kept thinking about it.

The following winter, having journeyed to Ottawa to referee a National Hockey Association game between the Ottawa Silver Seven and Renfrew, I was ready with a suggestion when asked to handle an amateur playoff at Almonte between teams from Arnprior and Renfrew… I told the clubs’ officers of my face-off innovation and proposed that it be tried in the game coming up at Almonte. They agreed.

Waghorne explains that after that game, “the new face-off spread rapidly across Eastern Canada, and eventually all leagues, both amateur and pro, made it official.”

So, there it was from the man himself.

But there were still plenty of problems.

Leaving out the question of where the game around 1900 had been played, there was the fact that the National Hockey Association wasn’t formed until the winter of 1909–10. So, if the Renfrew-Arnprior game at Almonte had been “the following winter” as Waghorne remembered it, he had either tried out his new face-off as late as the 1908–09 season … or “the following winter” actually had to be closer to 1901 and therefore several years before the start of the NHA. Also, Ottawa’s early hockey dynasty didn’t become known as the Silver Seven until winning the Stanley Cup for the first time in the spring of 1903. (And only until about 1906.) So it seemed likely to me this had all happened between 1900 and 1906.

I knew (and confirmed with some quick online research) that hockey playoffs between the Upper Ottawa Valley Hockey League and the Lower Ottawa Valley Hockey League for the Citizen Shield (donated by the Ottawa Citizen) had begun around that time. In the winter of 1902–03, it turned out. So searching for a playoff game between Arnprior and Renfrew played in Almonte in 1903 or 1904 seemed like a good place to start.

It proved easy enough to find!

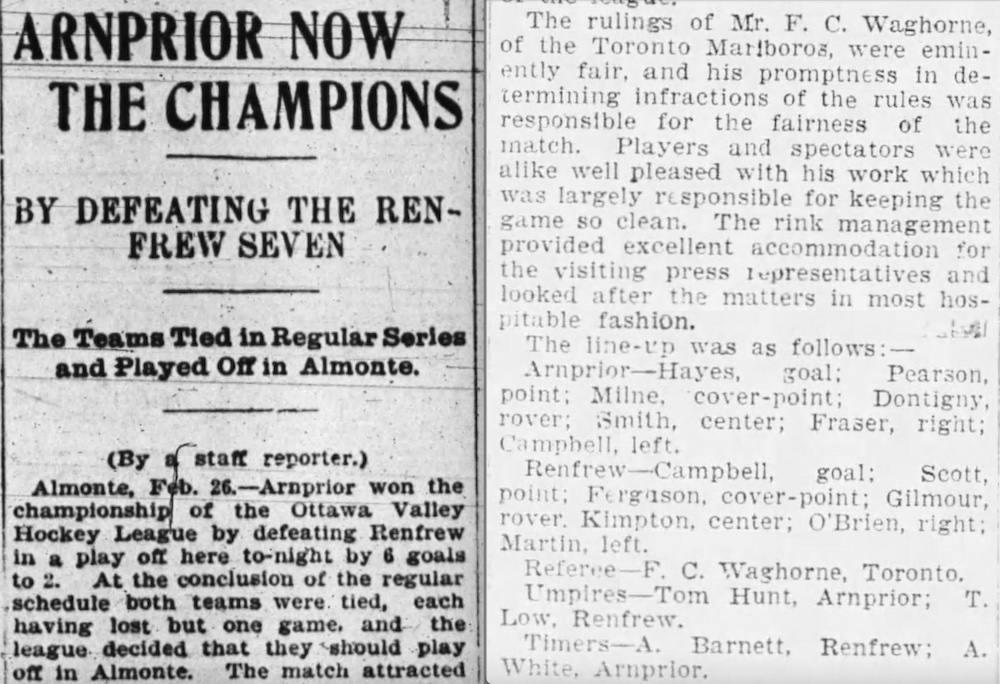

As it turns out, Waghorne journeyed to Ottawa late in February of 1904 — 120 years ago this week — when the Toronto Marlboros (for whom he was a club executive) faced the Silver Seven for the Stanley Cup on the 23rd and the 25th of that month. As it happens, on Friday night, February 26, 1904, Arnprior beat Renfrew 6–2 in a game played on neutral ice in Almonte to win the championship the Upper Ottawa Valley Hockey League and the right to meet the champions of the Lower Ottawa Valley Hockey League for the Citizen Shield.

The referee that night?

Fred Waghorne.

The game report in the Ottawa Citizen from Saturday, February 27, notes how “well pleased” everyone was with the job Waghorne had done. There’s also coverage in the Ottawa Journal that Saturday saying Waghorne “gave perfect satisfaction.” No mention in those game stories about face-offs, but in a further story about the game in the Ottawa Citizen on Tuesday, March 1, 1904, the unnamed writer goes to great lengths in explaining the fine job Waghorne did in keeping the two teams under control in a contest where “The crowd was prepared to be treated to a slugging match.” The writer later noted:

Another little incident that impressed the spectators as being an improvement over the eastern style of play was that, in facing the puck … instead of letting the two men bang it around, each trying to have the advantage over the other … the referee simply dropped the rubber between their sticks and the game was on the moment it touched the ice…”

So, it would seem that February 26, 1904, is the true start date for the modern face-off.

As to the earlier game where Waghorne first tried it, that’s proven harder to pin down.

Newspaper stories from his hometown in Toronto in the 1920s make it fairly clear that Waghorne didn’t begin to referee games in the Ontario Hockey Association until the winter of 1902–03. Maybe not until 1903–04. Prior that that, he only seems to be involved in hockey through local Toronto leagues.

Searching the Toronto Star, the earliest reference I found to Waghorne in the OHA comes on December 29, 1902, when it was reported he was a referee in the OHA’s Intermediate division. Group 12 in the OHA intermediate series had teams in Brantford and Paris. Group 13 had teams in Simcoe, Stratford, Ingersoll, and Woodstock. So, it it all fits pretty nicely. Then again, going through the Globe as well circa 1902 to 1904, it doesn’t look like Waghorne actually called OHA games on a regular basis until the 1903–04 season … which matches a Star Weekly story from March 24, 1928, saying he didn’t begin in the OHA until his friend William Hewitt (Foster’s father) became the league secretary in December of 1903. So, maybe all the face-off stuff actually happened during the 1903–04 season?

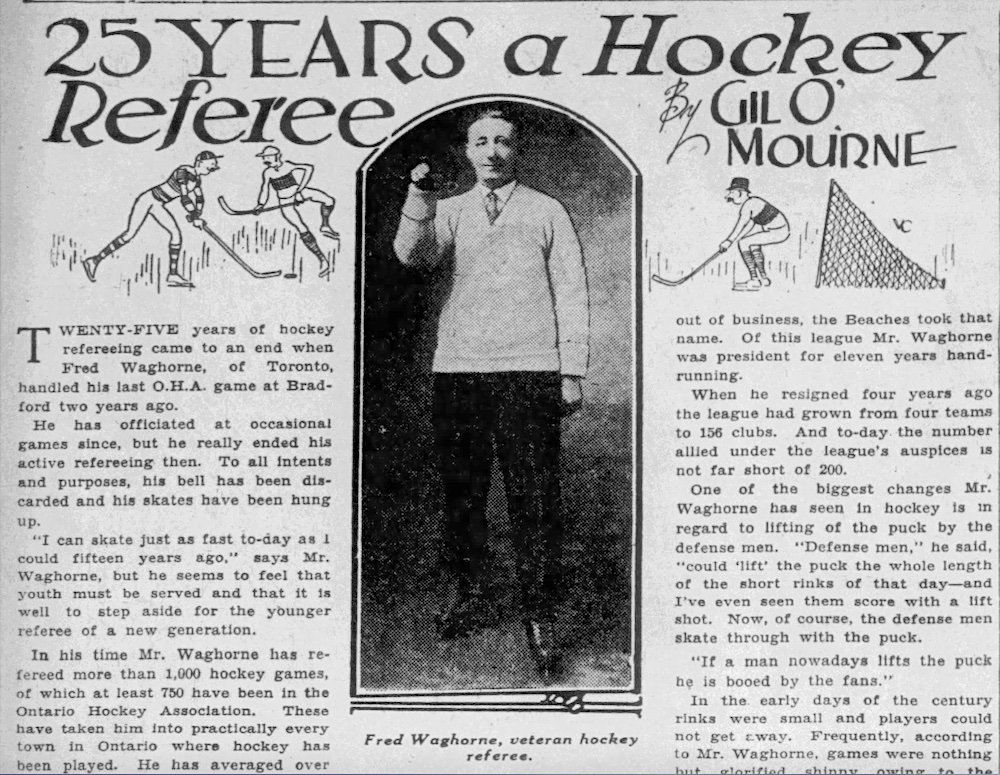

Of course, there’s always the chance that Fred Waghorne merely popularized something he’d seen from someone else and then outlasted them so that he became the “inventor.” That same Star Weekly story about his 25-year-career as a referee says only that Waghorne “was one of the first to introduce the dropping of the puck,” not THE first. Then again, no one else ever came forward to claim the distinction. So, if Waghorne was remembering correctly that the Arnprior–Renfrew game in Almonte had come “the following season” after his first face-off experience in Brantford, Paris, or Woodstock, there’s a decent chance that happened during the 1902–03 season. But maybe it really was earlier in 1903–04. (For what it’s worth, I’m beginning to like the chances that’s actually the case.)

No luck yet in tracking down a face-off story from any of those cities in those years.

Good luck to anyone who wants to take on that challenge … and I want to hear about it if you find it!

Oh, and about the bells and whistles, here’s what Fred Waghorne had to say about that in The Hockey Book: