Since moving to Owen Sound in the fall of 2006, I’ve done most of my work from home. And when I haven’t had a ton of actual paying work (freelancing can be pretty boom or bust), I often manage to keep myself busy reading and noodling away on my computer. So, I guess I’ve been better equipped than many to handle what’s become day-to-day life these days.

This story may read like the efforts of someone who’s got too much time on his hands (which I do right now), but, really, it’s not very different from what my “real” life was like before. It’s also a pretty good example of why I always try my best to help anyone who contacts me with a question as quickly as possible … because I often have to rely on similar help myself. And when I do, I like to get my answers NOW!

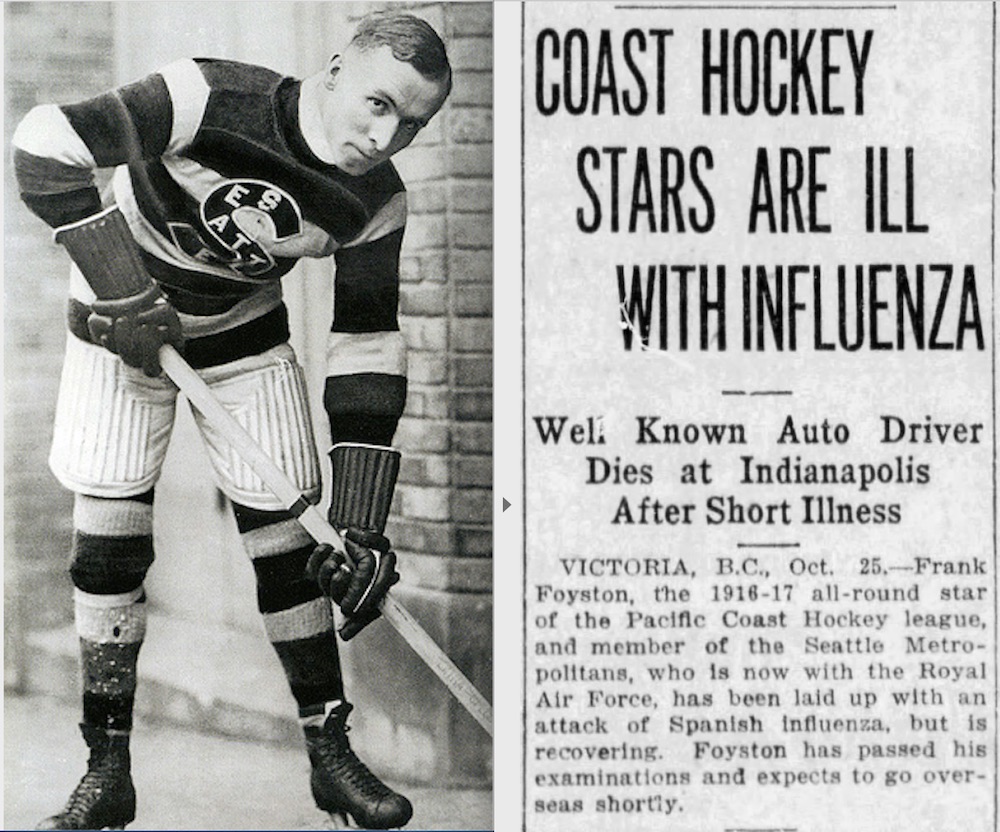

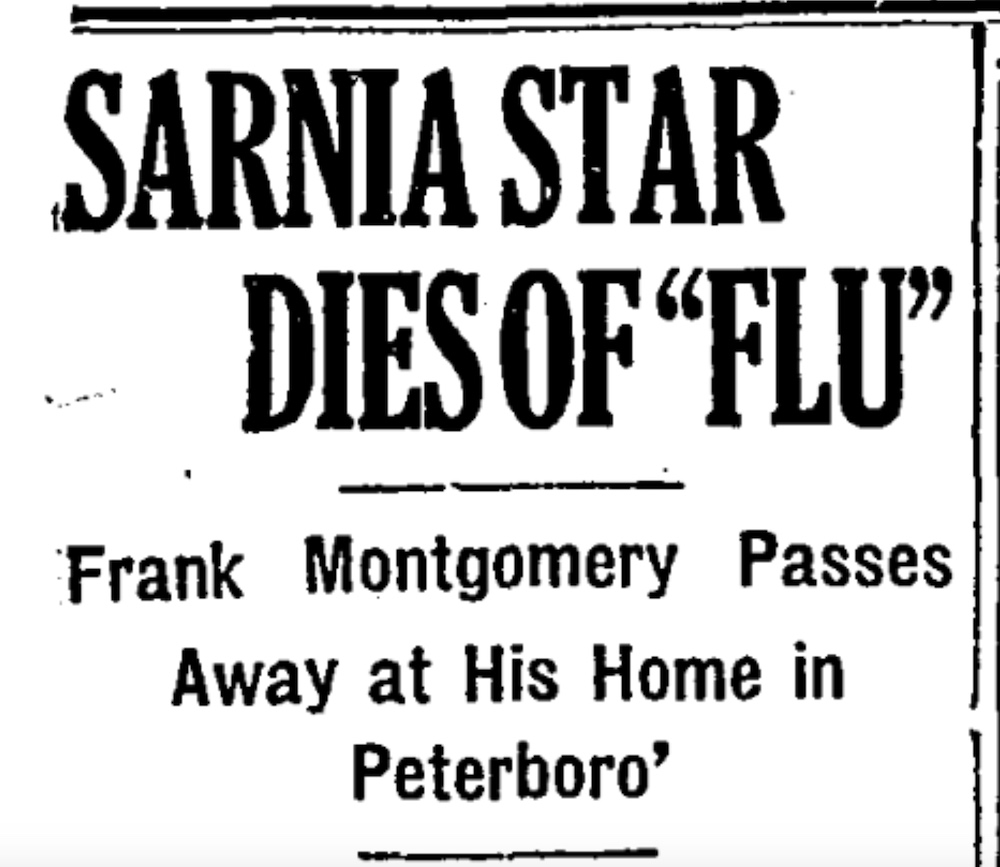

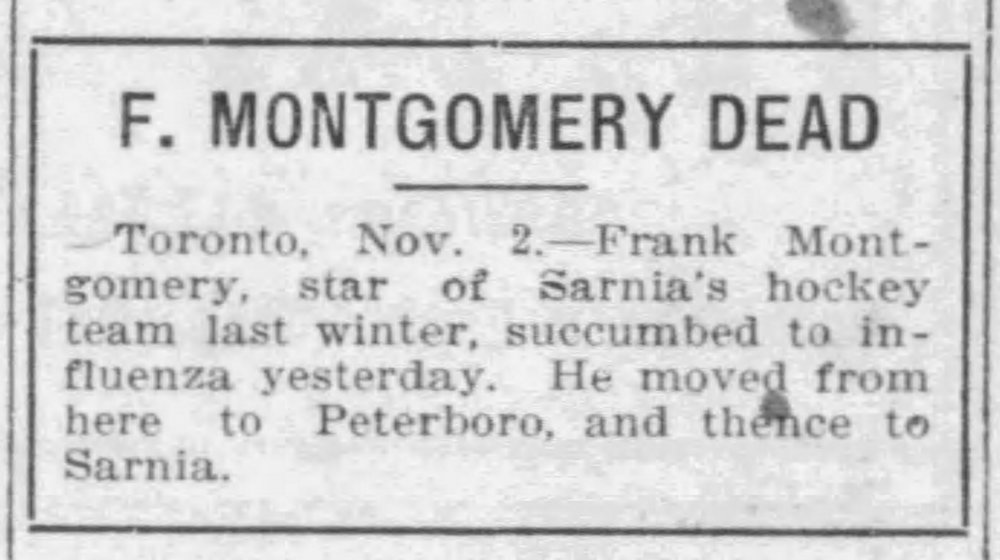

In my Spanish Flu story last week, I said that I was limiting myself to how the pandemic affected pro hockey players. Still, the story of one amateur player that popped up in my research stuck in my mind. His name was Frank Montgomery.

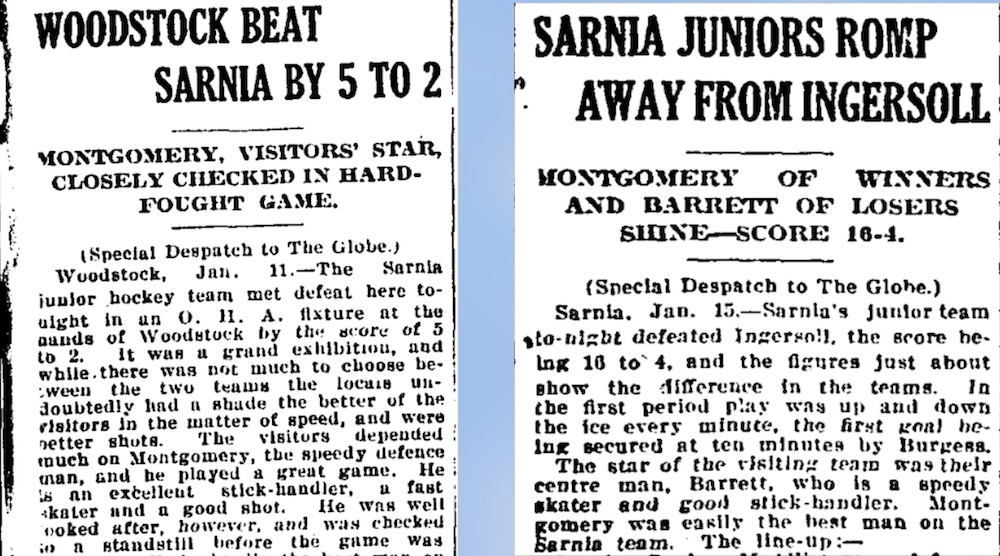

Montgomery was not someone I’d heard of before, so I started doing a little digging. I began with the web site of the Society for International Hockey Research. No one by the name of Frank Montgomery showed up in the statistical database. However, there were eight players with the last name Montgomery and no first name. Only two of them had stats ranges that made sense, and only one of those two had an entry showing that he’d played in Sarnia in 1917–18. There was no other information. No first name; no date of birth or death; no statistics; no other seasons.

A little more searching through old issues of the Globe online determined that a Montgomery did play in Sarnia in 1917–18, and that he was a defenseman. Better than the nothing that was there for him before, so I sent along what I’d found to my friend and fellow SIHR member Aubrey Ferguson.

The short obituary in the Globe had already told us that Frank Montgomery was from Peterborough, Ontario, so Aubrey passed along the information to a Peterborough SIHR colleague, Peter Pearson:

Hi Peter

Thought you would find this interesting, if only to put a Ptbo hockey twist on the Spanish Flu. Also thought you might have something from local sources on him.

Cheers, Aubrey

Following the email chain that would soon make its way back to me, Peter contacted Sylvia Best, who found a much more detailed obituary from the Peterborough Evening Examiner on October 28, 1918. There was plenty more information on Frank Montgomery in there, as well as the sad fact that not only had the family suffered his death from the Spanish Flu, but they had also learned at almost the exact same time that another family member had been seriously wounded fighting in World War I:

Frank Montgomery Died This Morning

- The Deceased Was Well Known in Local Athletic Circles -

Word was received late this after noon that Mr. Frank Montgomery had succumbed to pneumonia in Oshawa this morning. Mr. Montgomery had been ill with pneumonia for 12 days which succeeded Spanish influenza. Mr. Montgomery played on the Peterboro Junior O.H.A hockey team for Peterboro in the season of 1916-17. Last winter he played for the Sarnia team. He left for Oshawa in the latter part of July where he intended playing hockey this winter. The deceased also played for the Matthews-Blackwell team in the Twilight league.

The body will be brought to the city and the funeral will take place from the residence of his sister, Mrs. Thomas H. Skinner, 354 Stewart Street to Little Lake Cemetery. Rev. Mr. MacKenzie of Knox Presbyterian Church will officiate.

Mrs. Skinner received word on Saturday night that her husband Pte. Thomas Skinner of the 21st Canadians, had been badly wounded.

A big thank you to Peter and to Sylvia (neither of whom I know) and to Aubrey for their efforts … but I was still curious.

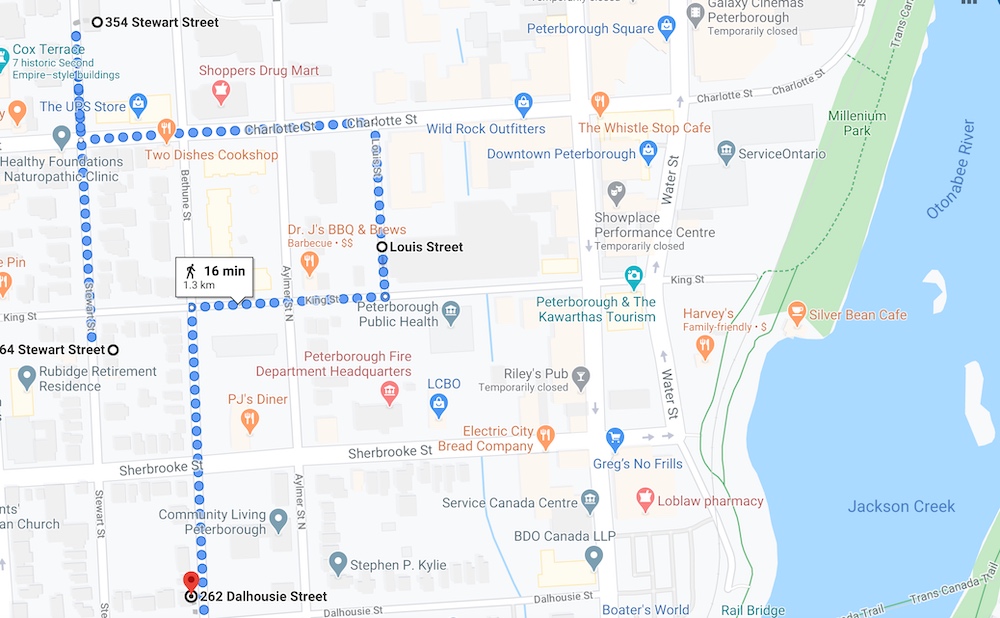

For one thing, I went to Trent University in Peterborough from 1982 to 1985. In my last year there, I shared a house with a few friends. It was on Stewart Street in the same part of town! What were the chances that I’d actually lived in that house? (Turns out, I didn’t. We were about two blocks away, at 264 Stewart.)

been enlarged since I lived there, and the ramp has been added.

Really, what I hoped to find was a birth date for Frank Montgomery. The Spanish Flu was notorious for killing men and women in the prime of life, with a huge percentage of deaths occurring in people between the ages of 20 and 40. As a junior hockey player, Montgomery was likely to be under 21. So — though I know they can be notoriously unreliable — I turned to the records of the Canadian census for 1901 and 1911.

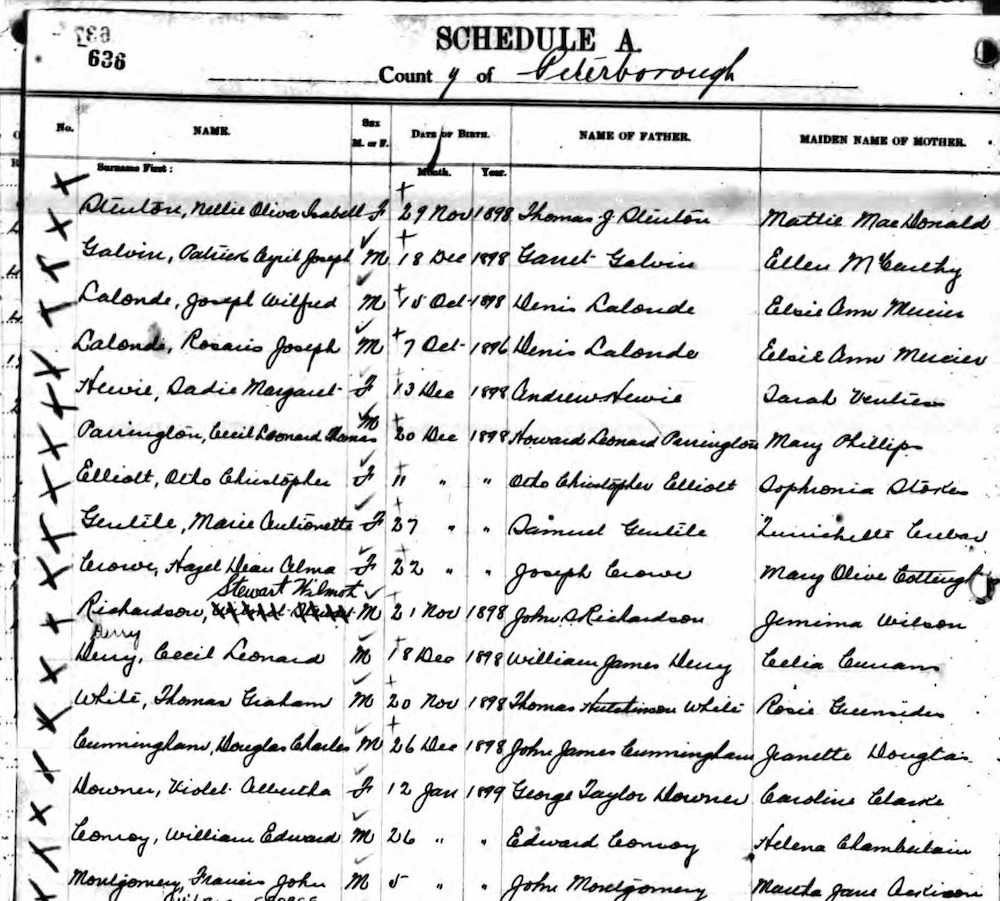

In 1901, I found a Montgomery family from Peterborough. (A later search through city directories showed the family lived at 33 Louis Street then … not too far from Stewart Street.) There was a father named John and a mother named Jane, plus four daughters … and then another daughter named Francis J.

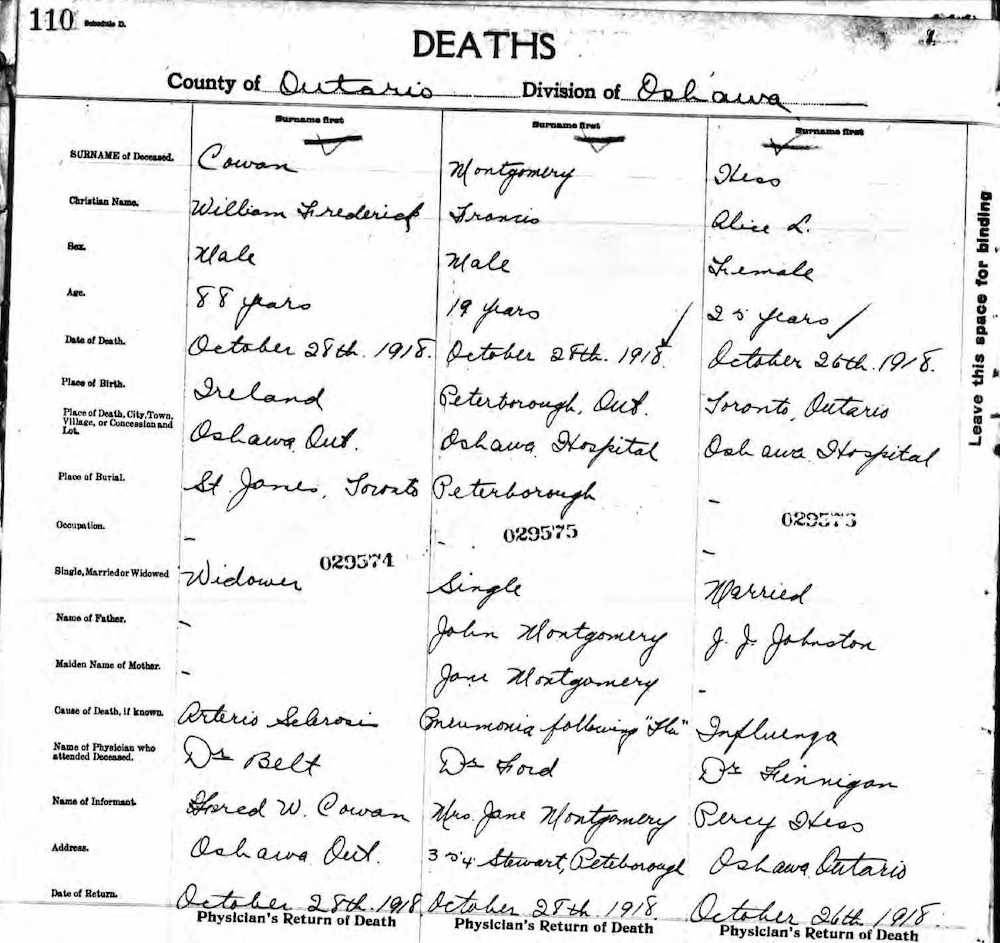

Francis J. would actually turn out to be our guy Frank. (The J. stands for John.) The birth date in 1901 is listed as January 7, 1899. By the 1911 Census, father John is no longer there. (I would later discover that he’d driven a team of horses for the fire department, and that he passed away around 1907. NOTE: Daniel Doyon found the death certificate confirming that John Montgomery died of pneumonia on Jan. 19, 1907.) Jane is now the head of the household and youngest daughter Geraldine is still at home. (The much smaller family by then was living at 262 Dalhousie, in the same neighbourhood.) Frank is now a boy, at least, but his birth is listed as July of 1899, not January.

As I said, those old Censuses can be unreliable…

However, in both 1901 and 1911, the family also has boarders in their home. In 1911, two of those boarders are T.H. Skinner and Edith Skinner. I assumed that Edith (there had been an Edith Montgomery in 1901) must be the sister from the obituary who was married to Thomas Skinner, and he must be the T.H. from the Census.

I knew I’d be able to confirm all this if I still had a membership to Ancestry.com but I’d cancelled that a while back. So, friends to the rescue once again! I called on Lynda Chiotti to ask if she could hunt down a birth record for Frank Montgomery, his death certificate, and anything on the marriage of Thomas and Edith when she had some time.

Meanwhile, as I waited to hear back from Lynda, I was also curious as to whether or not Thomas Skinner had survived the war wounds mentioned in Frank’s obituary. I was able to find his complete military record through Library and Archives Canada. Turns out, Thomas Skinner suffered gun shot wounds in his arms and legs on October 24, 1918, but survived and returned safely to Canada in 1919. (Thomas and Edith were still living with Jane Montgomery, and Frank, at 262 Dalhousie Street when Thomas enlisted in 1915, but both Thomas’s war records and the Peterborough city directory show their address as 354 Stewart by 1917.)

Lynda did find the marriage record for me. Skinner, Thomas Henry, was a carpenter who married Edith Maud Montgomery, daughter of John and Jane, on November 9, 1909. She also found a family tree showing that Thomas lived until September 19, 1960 and that Edith died on March 5, 1974, when she would have been nearing 100 years old. (City directories help to confirm this.)

As for Frank Montgomery, the birth records show that he was actually born on January 5, 1899, in Peterborough, to John and Martha Jane Montgomery. The death certificate confirms that he was only 19 years of age when he died in Oshawa on October 28, 1918. The cause of death is listed as “Pneumonia following flu.” The body was turned over to Mrs. Jane Montgomery, 354 Stewart, Peterborough.

All the pieces of this sad story fit. Still, it was satisfying to put them all together.

Well, maybe not all the pieces. The family tree that Lynda found actually shows Frank Montgomery listed as the son of his sister Edith! Edith Montgomery would have been about 22 (and unmarried) when Frank was born, while Jane would have been about 42. So, it’s certainly possible that grandmother Jane raised Frank as her own … but it might just have been an error in the listing. As of now, there’s been no way to know for sure. Family histories can certainly be mysteries.