A few days ago, I got an email from my friend Tosh suggesting that perhaps a story about the Uke Line might be of interest these days. I haven’t taken a lot of requests on this web site. As I indicated in my most recent post, I don’t usually give a lot of thought to what story comes next. Something usually just pops up.

In his email, Tosh included a link to an online post from The Ukrainian Weekly that gives a pretty good history of the Uke Line. (You can read it here if you’d like.) But he wondered if I had something from my own “unique perspective” to add to the story.

Well, I did know of one thing. And sort of stumbled on to some other things too. So, here we go…

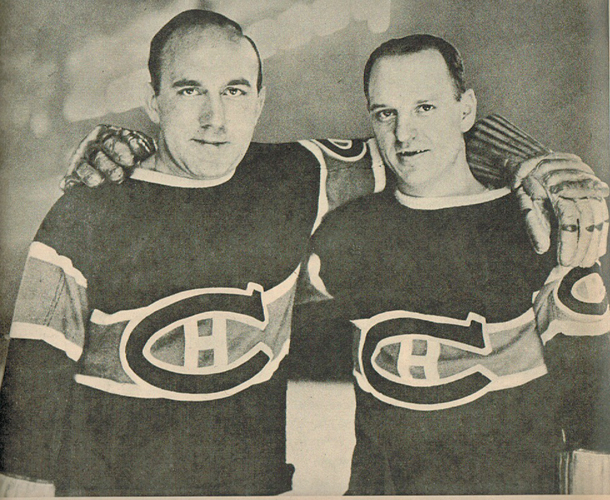

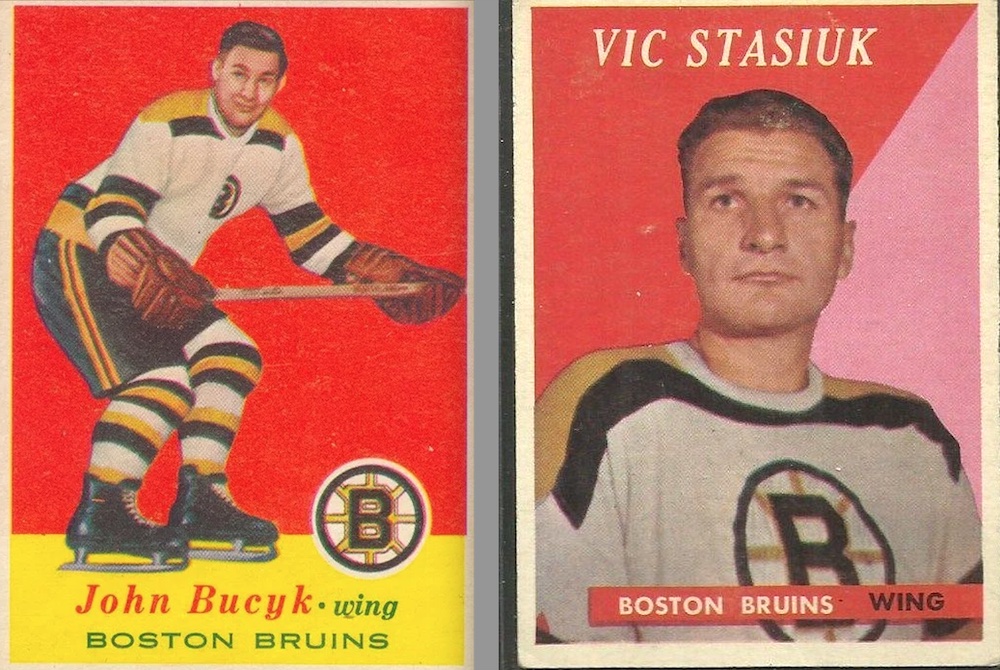

Having all played together in the minors with the Edmonton Flyers of the Western Hockey League in 1954-55, the Uke Line was formed for the 1957-58 NHL season after the Boston Bruins acquired center Bronco Horvath and left winger Johnny Bucyk in a couple of separate transactions. At training camp, the two newcomers were teamed with right winger Vic Stasiuk (who had been with the Bruins since 1955). They were a big success and by the midway point of the NHL season, the Boston trio trailed only the Montreal line of Maurice Richard, Henri Richard, and Dickie Moore as the top-scoring unit in the NHL.

On January 6, 1958, Herb Ralby of The Boston Globe wrote that back in training camp, Bruins coach (and former star) Milt Schmidt had “remarked that the new Uke Line reminded him of his Kraut Line,” Boston’s high-scoring trio of the late 1930s and 1940s. Schmidt was impressed by the way Horvath, Stasiuk, and Bucyk “were forever huddling to talk over mistakes and possible plays.”

“When Bobby (Bauer), Woody (Dumart), and I were playing on the Kraut Line,” Schmidt said, “we always huddled after rushes in practice to talk things over. We also were inseparable. We lived together, ate together, and went out together as well as playing together. The Ukes do the same thing. That’s what makes a good line.”

In The Boston Globe of January 18, 1958, Ralby wrote that Horvath, Stasiuk, and Bucyk had rented the home of former Bruins defensemen Pat Egan and were living together there. All three apparently enjoyed cooking, and they ate a “varied menu,” although it was always steaks on game day.

“We usually buy $7 worth of steaks,” explained Bucyk. “They’re really good size. Vic broils them while Bronco is the salad man. He’s good at it too.”

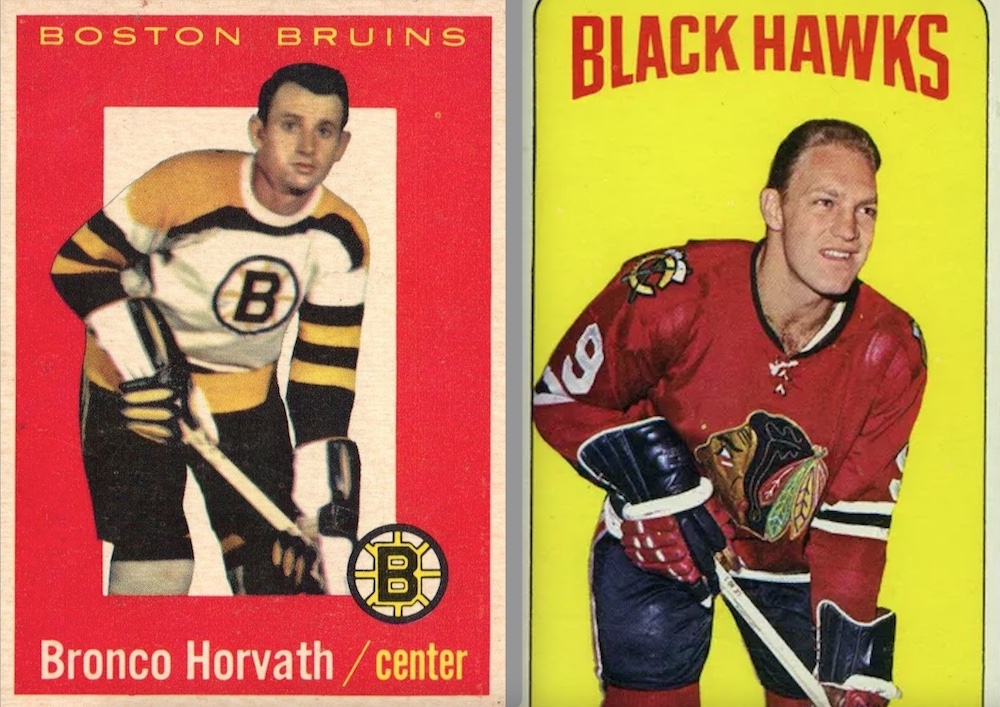

The Uke Line had a strong season in 1957-58, slumped a bit in 1958-59, and enjoyed their best year together in 1959-60. In fact, Bronco Horvath found himself in a tight race for the NHL scoring title with Bobby Hull that year. It went right down to the final game of the season, which pit Hull’s Chicago Black Hawks (two words in those days) against Horvath’s Bruins.

Horvath had 39 goals and 41 assists for 80 points heading into he finale at the Boston Garden on March 20, 1960. Hull had 38 goals and 41 assists for 79 points. The Golden Jet equalled Bronco with his 39th goal early in the second period, and picked up his 42nd assist and 81st point when he set up Eric Nesterenko with just 6:59 left in the game. Horvath was kept off the scoresheet all night, and when the game ended in a 5-5 tie (no overtime in those days), Hull had won the scoring title by a single point.

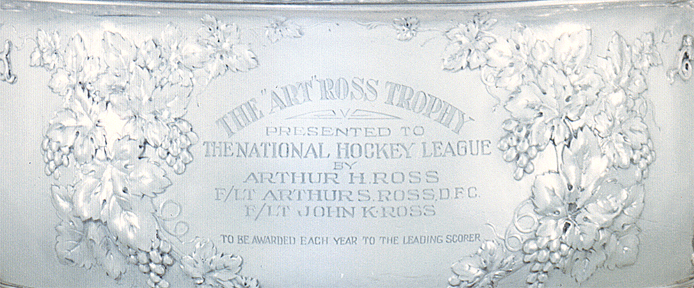

Some time after the season ended, Bruins radio play-by-play man Fred Cusick interviewed longtime former Bruins coach and executive Art Ross on a sports program Cusick hosted from the Clubhouse restaurant in Boston’s Kenmore Hotel. Ross, of course, is the namesake of the trophy given to the NHL scoring leader, which he and his sons, Arthur and John Ross, donated to the league after the 1947–48 season.

In earlier years, Bruins stars Cooney Weiland (1928-29), Milt Schmidt (1939-40) and Bill Cowley (1940-41) had all led the NHL in scoring. Ross told Cusick that when he had the honour of presenting his new trophy to Elmer Lach of the Canadiens at the Montreal Forum in 1948, “I said then I hoped I’d live long enough to see one of the Bruins players win it.

“This was my big year,” said Ross, “so I was really disappointed.”

Later, Phil Esposito (five times) and Bobby Orr (twice) combined to win the Art Ross Trophy for seven straight seasons from 1968-69 through 1974-75, but Ross had passed away in 1964 so he never got to see a Bruin win his trophy.

Bronco Horvath was the closest Ross got.

But was Bronco Horvath actually Ukrainian?

Before I started writing this, I was pretty sure I remembered reading somewhere that one member of the Uke Line didn’t actually have Ukrainian heritage. Wikipedia notes that Horvath was born to an ethnic Hungarian family that emigrated from Transcarpathia after the end of World War I, when it became part of Czechoslovakia. It does appear as though that region has also been part of Ukraine over the years … but I don’t know enough about the history to say that for certain.

However, Elmer Ferguson wrote in the Montreal Star on January 9, 1958, that he had received a letter from a proud Hungarian Canadian taking him to task “for referring to the Uke Line as a trio of Ukrainian boys,” on a recent Hockey Night in Canada Broadcast.

“We believe that you, Mr. Ferguson, owe Bronco Horvath an apology…” wrote George Horwath of Leron, Saskatchewan. “I have the acquaintance of several fine Canadian Ukrainians. None have intimated that they wish to be known as Hungarians, and for the same reason we Hungarians wish to keep our racial identity in tact…. [A] public retraction of your error will, I am sure, suffice the rest of us Canadian Hungarians.”

Elmer Ferguson wrote that, “Our humble apologies go forward at once, and in these, we hope, the Bruins publicity department headed by the esteemed Herb Ralby, will join us.”

Still, Bronco Horvath was inducted into the Ukrainian Sports Hall of Fame in 2019 (Bucyk was inducted in 2017; Stasiuk in 2018).

So – as I often say – “Who is knowing?”

[NOTE: It turns out that Fred Addis, president of the Society for International Hockey Research, and a native of Port Colborne, like Bronco Horvath, is knowing! Have a look at the post at the bottom of the comments below.]