Are bigger nets the answer to more scoring in the NHL?

The debate has come up from time to time since the end of the lockout that wiped out the entire 2004-05 season. Goalies these days are bigger than ever, and the NHL has made an effort to reduce the size of the equipment they use. Still, there seems to be little appetite for increasing the size of the nets from the 6-feet-by-4-feet they’ve always been since netting was first draped over metal posts in 1899. Tradition is often given as a reason in the arguments against enlarging the nets, but surprisingly, such talk dates back a lot further than people probably think.

With scoring in the NHL down considerably in 1926-27, sports editor Frederick Wilson of The Globe in Toronto noted in his column on February 21, 1927, a suggestion made in New York to widen the nets to seven feet. Nothing come of it, and scoring continued to drop, reaching an all-time low in 1928-29. Only 2.8 goals per game were scored on average that season by both teams combined, meaning the typical score was 2-1 in overtime. This is the year that George Hainsworth set records with 22 shutouts during the 44-game schedule and an average of 0.92. Every one of the NHL’s 10 starting goaltender had an average of 1.85 or better, and eight of them had at least 10 shutouts. More modern passing and offside rules were introduced in 1929-30, and offense jumped to over six goals per game. However, scoring dropped dramatically again in 1930-31, although it wasn’t nearly as low as it had been at its worst.

Even so, the Mercantile League in Toronto (which played out of the Ravina Rink, near Keele and Annette) was given permission by the Ontario Hockey Association and the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association to experiment with nets that measured 7½ feet wide from January 28, 1931, until the end of its regular-season schedule in March. The new nets resulted in a few games with scores as wild as 10-5, but most were still 3-1 and 2-0.

Maple Leafs boss Conn Smythe loved the wide nets. He wrote letters to NHL president Frank Calder and his fellow governors inviting them to Toronto to see for themselves. Smythe, Calder and Leo Dandurand attended a Mercantile league doubleheader on February 18, but Mike Rodden, writing in The Globe the next day, noted that the teams “proceeded to give their worst displays of the season.” (The games were 3-3 and 3-1, Rodden worked both as referee, and elsewhere in The Globe it was noted that they were marked by “exceptional goalkeeping.”) Calder and Dandurand were unimpressed, though the NHL president noted that the nets didn’t strike him as alarmingly wide.

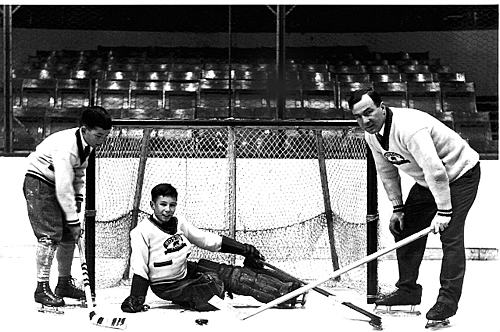

Given the animosity between them, it’s entirely possible that Conn Smythe supported the wider nets simply because Art Ross had designed the ones the NHL had been using since 1927-28. (The Art Ross net would be used without change through the 1983–84 season, and all the new nets used since then are still just a variation of his original design.) The 6-by-4 size had been well established long before then, but Ross still became the go-to guy whenever talk of the nets came up. It’s unlikely he saw any of the wide-net games in Toronto in 1931, but he did give his thoughts on the experiment to Boston Traveler hockey editor Ralph Clifford. “Adhere to the rules,” Ross said. “Have them strictly enforced … and you will have a game that is wide open enough to satisfy the most exacting fan.”

Art Ross with sons Arthur (the goalie) and John. Courtesy of Art Ross III.

People don’t think of the heyday of Gordie Howe and Maurice Richard as a low-scoring era, but the 1952-53 season saw only 4.8 goals scored per game. Once again, people wondered about widening the nets. “Somebody brings that up every time the defense gets ahead of the offense for a while as it is right now,” Tom Fitzgerald quoted Ross as saying in the Boston Globe on November 28, 1953. “We’ve gone through a lot of different phases like this, and certainly the hockey has been interesting this season, even if fewer goals are being scored… Increasing the width of the nets a little wouldn’t boost scoring to any great extent.”

Speaking about scoring again a few days later, Ross said: “It’s pretty simple. The more you keep shooting at the net, the more chances you have to score. There are a lot of factors that are going to help if you pour enough shots at a goalie – deflections, funny bounces and the like. If you just keep shooting away the percentages will work out for you.”

But chances are, Art Ross never envisioned a game where players blocked shots like they do today, or one where goalies were so large, agile and well padded. He’d been involved with the game at its highest levels since 1905 as a star player and then an executive, but Ross never seemed to be bound by tradition. It would be interesting to see where he’d stand on enlarging the nets if he were alive today.