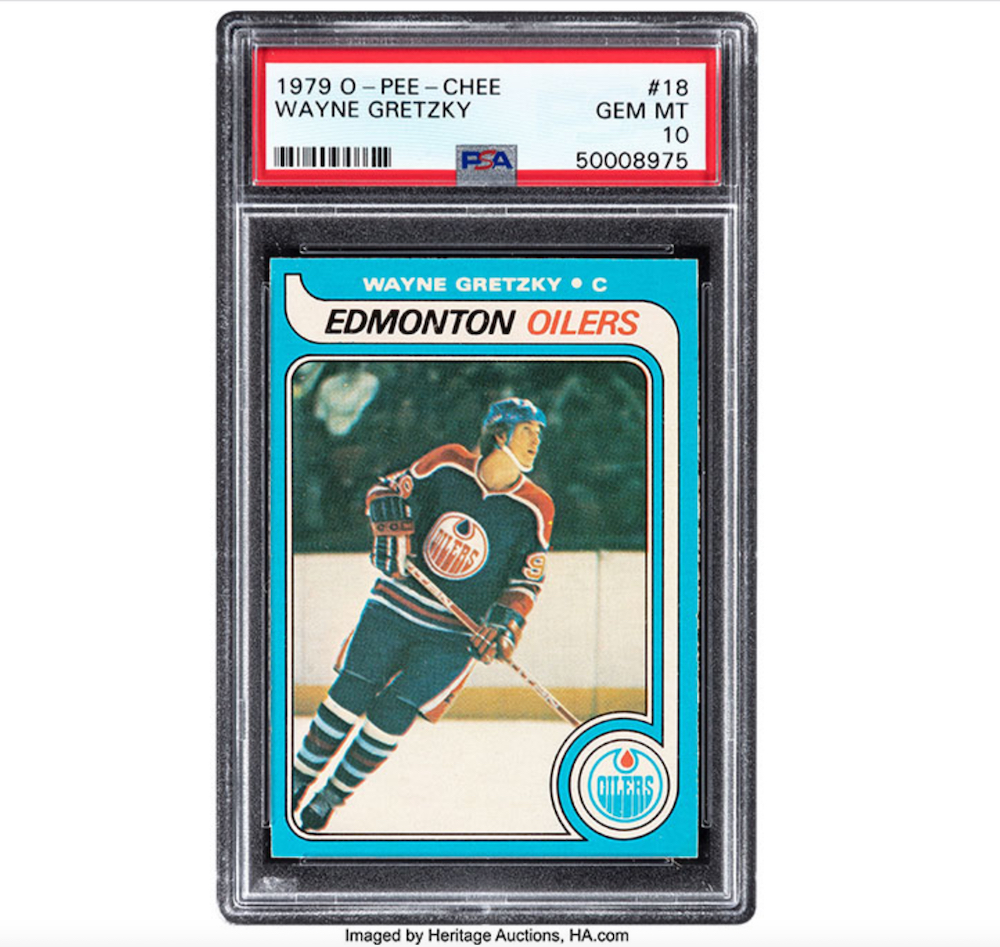

Last week, a Wayne Gretzky hockey card sold at auction for $1.29 million. It was a 1979 O-Pee-Chee Gretzky rookie card and it set a new record as the first hockey card to sell for over $1 million. (O-Pee-Chee produced hockey cards in Canada, and the Canadian cards are more valuable than the identical American hockey cards of the time produced by Topps.) [NOTE: The record was smashed on May 27, 2021, when a Gretzky rookie card sold for $3.75 million.]

Apparently, this Gretzky card is one of only two from his 1979–80 NHL rookie season to have earned a “Gem Mint” rating from PSA (Professional Sports Authenticator) out of the 5,700 or so that have been certified. In a story by Kevin McGran in the Toronto Star last week, Chris Ivy of Heritage Auctions in Dallas (who sold the card) said even brand new O-Pee-Chee cards in 1979 would have had difficulty earning a top rating due to the poor paper quality used, the wires used to cut the cards, and the issues they often had with poor centering.

The record-setting Gretzky card certainly looks to be well-centered, with no folds or chips in the paper. And, apparently the slightly jagged edge on the right side only adds to its authenticity in an age where it’s easier than ever to fake these cards.

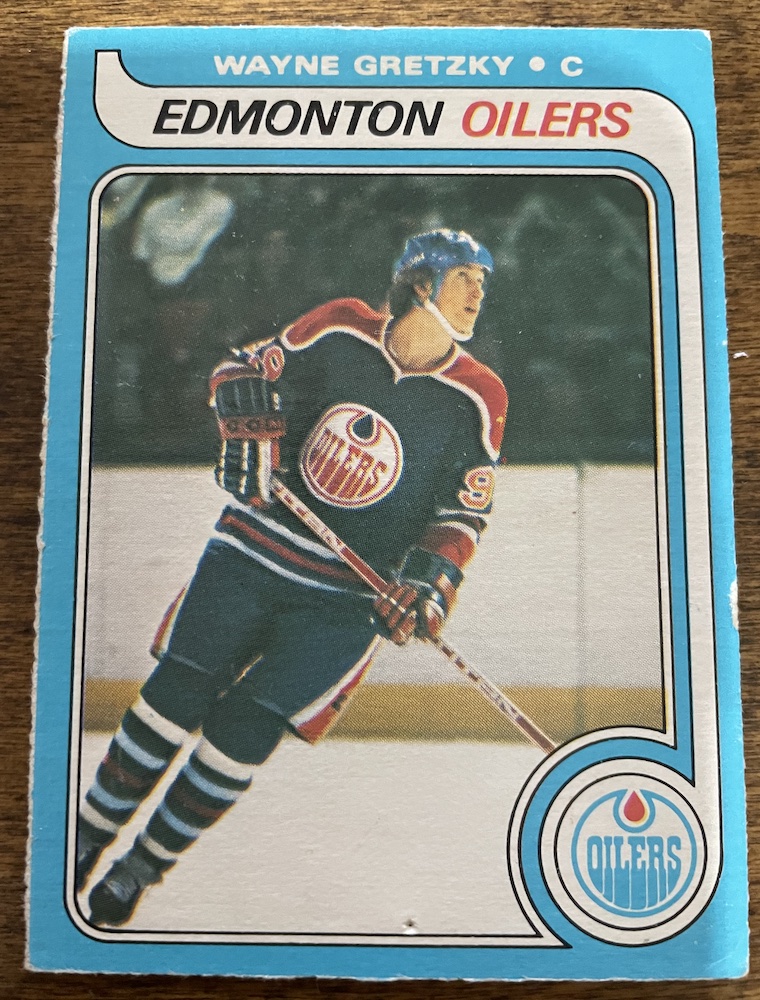

So, hey, collectors! If you like jagged edges, check out this Gretzky rookie card that belongs to my brothers and me. (David was the biggest Gretzky fan in the family, so he has it at his house.)

The edges are definitely rough! There are some issues with the corners, and some of the blue edge has worn away, probably where somebody’s thumb handled it too often. The centering looks good, but the biggest issue to a collector would be the hole from the push-pin near the bottom.

And therein lies, (as Paul Harvey used to say), “the rest of the story.”

My brothers and I were, essentially, children of the 1970s. Children of the 1970s — like the generations before them — may have enjoyed collecting sports cards, but we didn’t preserve them for their future value. We played with them!

Farsies. Topsies. Knock-Downs. Scrambles. (Some times for fun, sometimes for Keepsies!)

I don’t think any of the Zweig brothers ever put their cards in the spokes of their bikes, but David and I definitely had our own, special game for them. We would take the plastic nets off of our table-top hockey game and put them on the floor. We’d put a goalie card leaning up in front of each net, then we’d grab a card in each hand, get down on our hands and knees, and whack around a marble (and each other!) while trying to score on the other one’s goalie. Most of the hockey cards we have to this day still have creases that bend perfectly between four fingers and a thumb.

Our Gretzky card didn’t get that kind of treatment. Not because we were thinking of its future value, but because David and I were now 15 and 17 years old and less likely to crawl around on the floor body-checking each other.

David and I were both big Gretzky fans. As I wrote back in February, we’d been so since February of 1978 when our father took all three of us to see Gretzky play for the Sault Ste. Marie Greyhounds against the Toronto Marlboros at Maple Leaf Gardens. We followed him in the newspapers in the WHA in 1978–79 and, I saw Gretzky play for the Edmonton Oilers against the Maple Leafs at the Gardens the first two times they played there in 1979-80; once in November and once in March. Gretzky had two goals and four assists in the March 29 game (the Oilers beat the Leafs 8-5) to close in on Marcel Dionne for the NHL scoring lead, and it was amazing!

When card collecting was huge in the 1990s, I bought these two 1910 hockey cards because of their connection to my first book, Hockey Night in the Dominion of Canada.

If I’m remembering correctly, I paid $250 for Lester Patrick and $225 for Cyclone Taylor.

I saw the first Gretzky game on November 21 with my friend Mike Baum, who we called “Guy” because he loved the Canadiens. (Gretzky had two goals and two assists in a 4-4 tie that night.) I saw the March game with Steve Rapp, and afterwards we waited around to get autographs. I got Gretzky’s on a scrap from a popcorn box. (I believe I got his linemates Brett Callighen and B.J MacDonald too.) Since David was the bigger fan, I gave him the autograph … and he pinned it to the bulletin board in his bedroom, along with the Gretzky card — because Gretzky was his favourite player.

So, there you go. The autograph hasn’t survived, but because of the pinhole damage (not to mention the damage from the tape on the back!) the value of our Gretzky rookie card drops from a potential $1.29 million to maybe $1.29 hundred.

If we’re lucky!

And, hey, if I don’t get around to posting anything again over the next 10 days or so, Happy Holidays to everyone and best wishes for 2021. (How could it not be a better year?!?)

NOTE: The autograph still exists too! David has kept it all these years. Says I promised I’d get it for him if he let me wear his Gretzky jersey to the game that night. (I remember that I wore it, but don’t remember the promise! He says “I couldn’t believe you came thru.”)