A few weeks ago, in conjunction with the Centennial Classic outdoor game between the Toronto Maple Leafs and Detroit Red Wings, the NHL announced the first 33 of the 100 Greatest Players to be named in honour of the NHL’s 100th season. These players played predominantly during the first 50 years of the NHL, from the first season in 1917-18 through 1966-67; the last season before the big expansion. This weekend, prior to the All-Star Game in Los Angeles, the 67 remaining members who have played mainly since 1967 will be announced.

One of the problems with lists such as these is that they always skew modern. I don’t know which current players will make the final cut. I would suspect that Sidney Crosby and Alex Ovechkin have to be there. But I also imagine there will be several guys who don’t truly deserve it yet because of the desire to appeal to current fans. Let’s face it, this is a celebration not a history lesson.

Making lists like these is a bit of a mug’s game. It’s impossible to please everybody. Some worthy players have already been left out, and others likely will be. While it’s hard to say that too many of the 33 choices so far don’t deserve the recognition, there are a few I probably wouldn’t have named. But my replacements might not be yours…

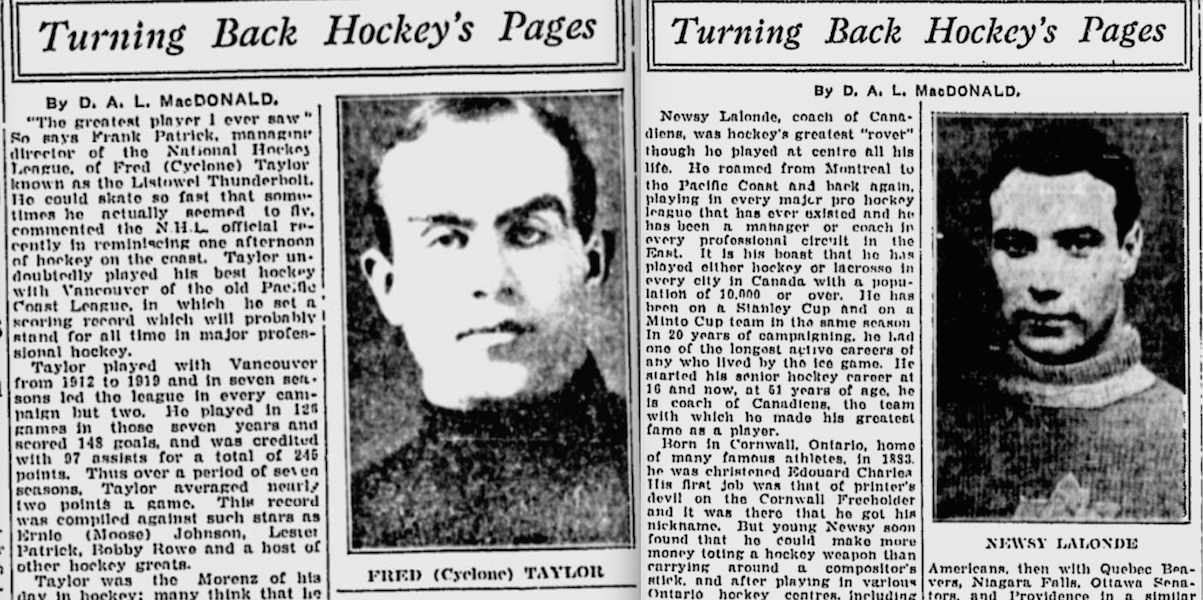

Undoubtedly, Gordie Howe and Bobby Hull (who were already stars pre-1967 but were not included in the early list), will make the final cut. I’m less confident that an early superstar like Newsy Lalonde will make it if he wasn’t named already. Same with Frank Nighbor, Cy Denneny, Joe Malone or Sprague Cleghorn. Time is cruel, and the fact that some of them had their best seasons before the NHL was formed probably doesn’t help their case either.

Still, one early era omission strikes me as the most glaring. And that’s Clint Benedict.

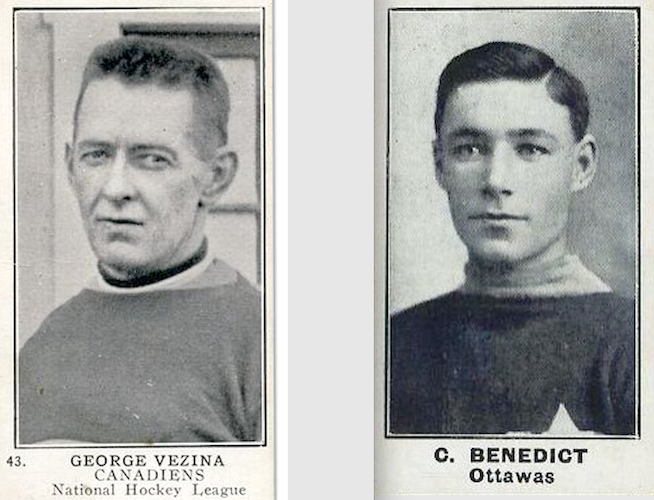

Everyone in the early days of the NHL knew that Clint Benedict and Georges Vezina were the best goalies in the young league. Along with Hugh Lehman and Hap Holmes, who spent most of their careers playing in rival leagues, these men were probably the best goalies in hockey history to that point. But of them, only Georges Vezina is a name most people recognize today. That is, of course, because since 1927, the NHL has presented the Vezina Trophy to the league’s top goaltender.

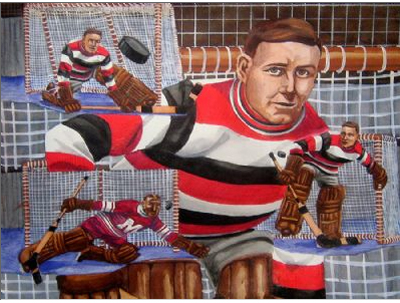

Paintings by Darrin Egan. Visit him on Facebook.

Paintings by Darrin Egan. Visit him on Facebook.

My friend and colleague Stu Hackel wrote a wonderful biography of Georges Vezina for the NHL Centennial web site. And I certainly don’t mean to disparage a legend. But if Vezina hadn’t collapsed of tuberculosis during a game and died about a year later (leading to the decision of Canadiens’ ownership to donate a trophy in his honour), the contemporaries he left behind likely wouldn’t have spoken quite so glowingly of him, and he’d have faded from memory with the rest of them.

For me, Clint Benedict was the best goalie of his era. Better than Vezina. Benedict led the NHL in wins in six of the league’s first seven seasons. He led or shared the lead in shutouts (not that there were many in his day) in each of the first seven seasons. He led in average six times between 1918-19 and 1926-27. He also won the Stanley Cup with Ottawa in 1920, 1921, and 1923 and added another with the Montreal Maroons in 1926.

According to all accounts, Vezina was stoic and played a standup style. Benedict was a flamboyant flopper whose habit of falling to the ice to stop the puck was a big reason why the NHL changes its rules early in its first season to allow goaltenders to leave their feet. Benedict was the Dominik Hasek of his day … but he was the Martin Brodeur too, playing behind a team in Ottawa that was really the first in hockey history to emphasize defense over offense. After all these years, it’s impossible to know if Benedict was really better than Vezina or just played behind a better defensive team … but we do know a few things.

In the Vezina feature in Turning Back Hockey’s Pages which ran in the Montreal Gazette on January 8, 1934, D.A.L. MacDonald writes of a story told by Leo Dandurand (the Canadiens owner in Vezina’s time who donated the trophy in Vezina’s name) about a game between Vezina’s Canadiens and Benedict’s Montreal Maroons.

Contact Darrin at: inthebluepaint@gmail.com

Contact Darrin at: inthebluepaint@gmail.com

“It will be a close battle,” Vezina said. “I can hold them out at my end, Leo, but it will be tough to score against them. The best man is in the other goal, you know.”

Modesty was apparently a Vezina quality, but Benedict’s own teammates certainly backed their guy.

“Georges Vezina, of the Canadiens was a great goalie then,” said former Senators and Maroons star Punch Broadbent in the Ottawa Journal on May 11, 1965. “He’s honoured with a trophy; practically legend in hockey. But we all thought there was no goalie ever better than Clint Benedict.”

Writing in that same paper on June 8, 1965 (the day after Benedict was named to the Hockey Hall of Fame), Journal sports editor Bill Westwick told this story:

“Vezina was the idol of many fans, especially the Montreal faction, but his own manager, the late Leo Dandurand, was a tremendous admirer of Benedict. There was a time when Dandurand told this reporter that he would have been very much tempted to have obtained Benedict in place of Vezina. That sounds like heresy in view of the legendary feats of Vezina, but Leo was the one to say it.”

You can’t always take these old sportswriters at their word, but if this story is true, that’s a pretty good mark in Benedict’s favour.

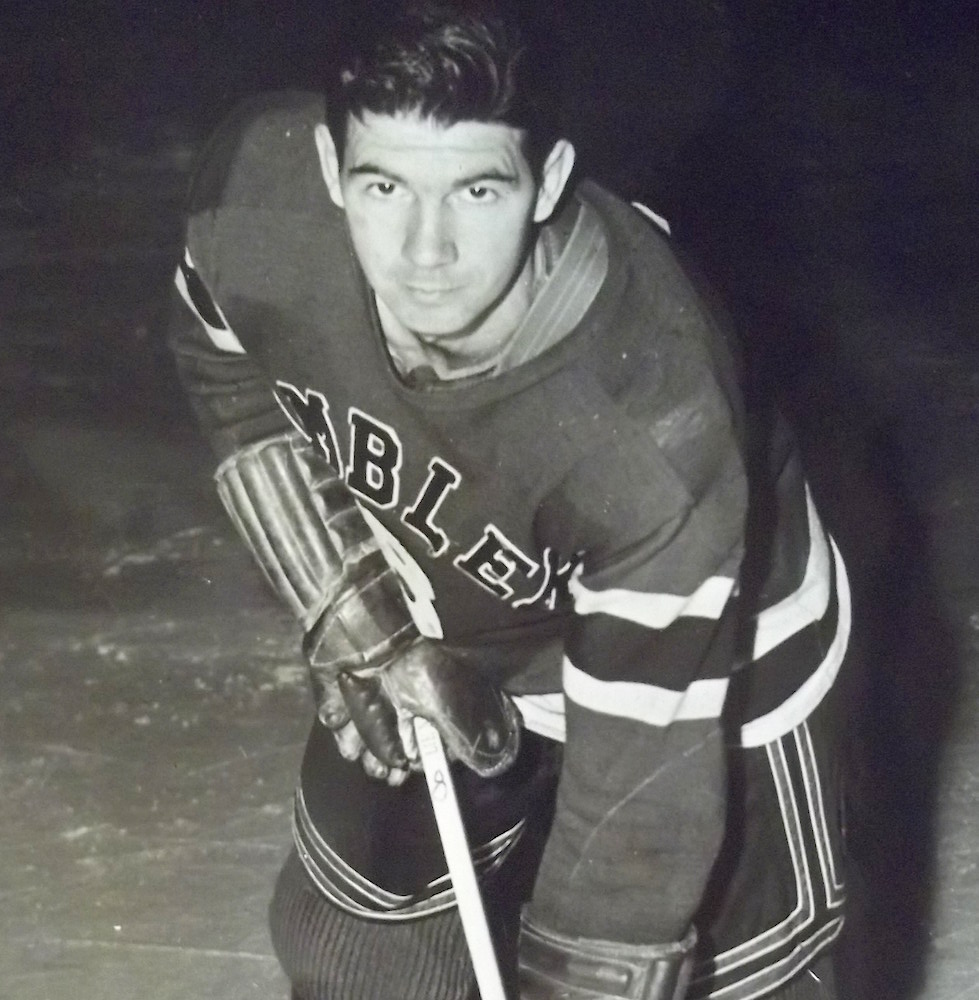

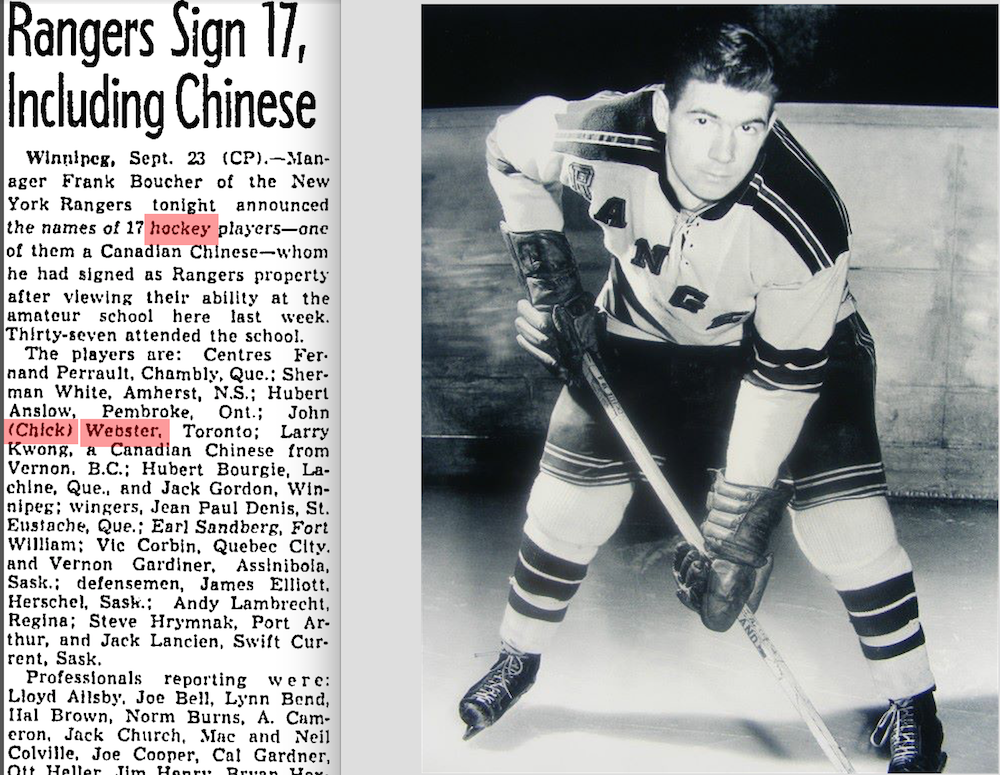

Chick Webster with the New Haven Ramblers, courtesy of Rob Webster.

Chick Webster with the New Haven Ramblers, courtesy of Rob Webster.

Globe and Mail, September 24, 1946. Photo courtesy of Rob Webster.

Globe and Mail, September 24, 1946. Photo courtesy of Rob Webster. Chick Webster enters the Cincinnati Mohawks dressing room and

Chick Webster enters the Cincinnati Mohawks dressing room and