Well, Hockey Day in Canada was supposed to be broadcast from Owen Sound 10 days from today on Saturday, January 29. Events were scheduled all around town from Tuesday to Friday leading up to it. Unfortunately, word came down two weeks ago that amid new provincial restrictions and a worsening surge of COVID-19 hospitalizations, it’s all been postponed until 2023. The day-long marathon broadcast will continue, but not from here.

I had provided research for the Owen Sound broadcast, about the city of Owen Sound and its hockey history for Hockey Day. I prepared notes on players from Owen Sound and its teams specific to the games to be broadcast, as well as general notes about events from the past, and local historians who might be able to speak to them.

There are several stories I would have loved to post on my web site, but I didn’t want to jump the gun on anything Rogers might choose to broadcast. Many will hold over until next year. Still, I’m posting this one now because, although it may well be something Rogers will still cover, there’s no way they’ll go into the quirky personal connection I have with this story.

When Rogers finally comes to Owen Sound for Hockey Day in Canada, it will probably be the biggest hockey circus to hit town since the fall of 1944 when the Toronto Maple Leafs held training camp here at the Civic Auditorium-Arena. (The Leafs would train in Owen Sound again in 1945.) I have long wondered how much the fact that Hap Day was from Owen Sound played a part in that decision. Day had been the Leafs’ captain from 1927 to 1937, and the coach since 1940. His Owen Sound roots couldn’t have hurt, but it was the mayor of the city who’d done the leg work to bring the Leafs here.

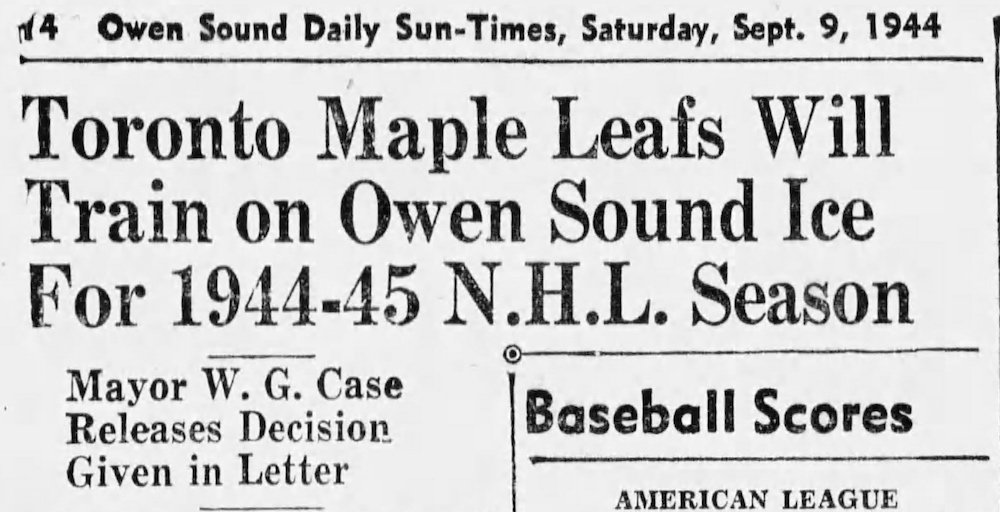

Talk of Toronto holding training camp in Owen Sound in 1944 had been rumoured around town since that spring, when Day and Leafs assistant general manager Frank Selke were the headline speakers at the local arena for a banquet held by the Owen Sound Hockey League on May 31, 1944. Mayor W. Garfield Case presided over the banquet, and after it was announced at a committee meeting of the City Council on September 8 that the Maple Leafs were coming to town, the Sun-Times newspaper reported the following day that Case “has been conducting negotiations with Maple Leafs management for some time regarding the team coming here to practice.”

That’s where my connection to the story comes in.

When we moved to Owen Sound in the fall of 2006, we moved into the Webster-Case House, previously owned by former Owen Sound mayors William Webster and Garfield Case.

Wilfrid Garfield Case was mayor of Owen Sound from 1942 to 1944. In 1945, he defeated Canada’s Defense Minister, General Andrew McNaughton, in a bye-election called specifically to give McNaughton a seat in the House of Commons. McNaughton had been parachuted in by the Liberals, but was opposed by Case of the Progressive Conservatives, who campaigned on the slogan “Send a Grey North man to Ottawa, not an Ottawa man to Grey North” and whose pro-Conscription position carried the day over the Liberals and Prime Minister Mackenzie King’s “Conscription if necessary, but not necessarily Conscription” view. Campaign meetings were held in Case’s home. Our home.

Case was born on September 23, 1898, and enlisted in the Canadian army during World War I. He later transferred to the Royal Flying Corps, but was discharged after being seriously wounded. He served Grey North as its Member of Parliament from 1945 to 1949, and was defeated again in the election of 1953.

Later, in July of 1959, Garfield Case was admitted to Sunnybrook Hospital in Toronto for psychiatric treatment. I remember someone telling us that Case had killed himself in a store in downtown Owen Sound. Turns out, that’s not true. He was actually found dead on September 22, 1959, in the chapel at Sunnybrook Hospital … though he had killed himself.

A neighbour told us that Case haunted our house, but that he was a friendly spirit.

A couple of people even told us they had seen the ghost.

We never had any spooky experiences!

But getting back to the Maple Leafs… when the announcement of their coming to Owen Sound was made at the City Council meeting, Alderman Jean Honsinger had suggested that “perhaps it will bring them a change of luck.” After all, the Maple Leafs had experienced two straight first-round playoff defeats since last winning the Stanley Cup … all the way back in 1942!

Most of the team arrived in Owen Sound by train from Toronto on the afternoon of October 10, 1944. Others would trickle in over the next few days. The players were put up in a couple of hotels around town, had access to a local gym, held practice in the Arena, and played golf on a local course. Coach Day, trainer Tim Daly, star player Babe Pratt and a few others took part in a radio broadcast on CFOS on Friday night, October 20 from the Paterson House hotel, where most of the team was staying. During their two weeks in Owen Sound, the presence of Toronto’s NHL stars gave the Sun-Times something else to report on other than the War news that filled almost every other page.

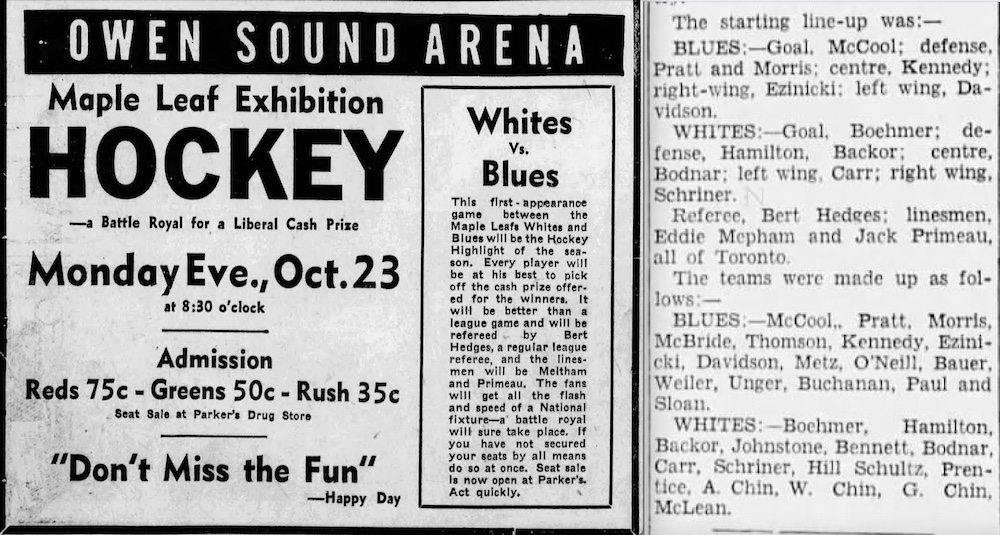

The Leafs played just one preseason game in Owen Sound on October 23, 1944. It was an inter-squad game featuring a Blue team against White. The Blues won the game before an overflow crowd while a storm raged outside. “From the windows could be seen flashes of brilliant lightning,” the Sun-Times reported the following day, “and during lulls in the cheering could be heard peals of thunder and the sound of [heavy rain] pouring on the roof.”

The Leaf packed up on October 24, moving to St. Catharines, where they played another Blue and White game that night before kicking off the season against the New York Rangers at Maple Leaf Gardens on October 28. “Well, the Maple Leaf hockeyists are gone,” wrote Joe O’Neill in a Casual Comment on Sport column in the Sun-Times on October 25, “and the fans in particular feel just a bit lonesome.”

During the time the Leafs had been in Owen Sound, “all of them from the coach to the least rookie, whenever one met them, proved themselves gentlemen of the highest type. They made for themselves a warm spot in the estimation of the people of this city and they will always be welcome…. Fans will follow their battles in the hockey wars with greater interest now that they have come into contact with them and know them.”

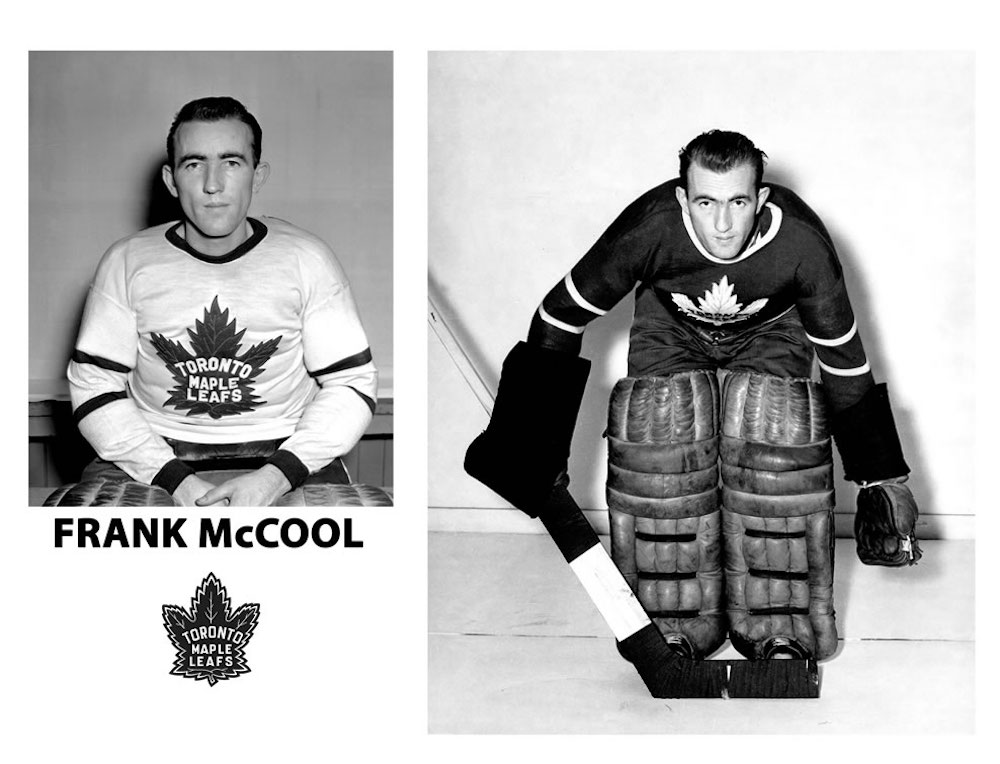

The biggest stories out of the Owen Sound camp were the appearance of the three Chin brothers from a Chinese family in nearby Lucknow, and the emergence of goalie Frank McCool. (With Turk Broda in the Army, the Leafs had stuggled to get decent goaltending the previous season.) McCool had played hockey with the Currie Army team in his hometown of Calgary in 1942-43 until ulcers forced his discharge from the Forces, and had sat out the 1943–44 season when the Rangers were scared off by his stomach troubles. He made his NHL debut with Toronto in the season opener in 1944 one day after his 26th birthday. McCool went on to win the Calder Trophy as rookie of the year in 1944–45 and, guzzling buttermilk to calm his ulcers during the Stanley Cup Final, led the Maple Leafs to that long-awaited NHL championship.

“If I were to single any one for individual praise I would have to say that of all the team, McCool has come farthest since Owen Sound,” said Hap Day after the Leafs’ seventh-game victory over the Red Wings on April 22, 1945. “At Detroit last night when it was all over McCool came up to me and said, ‘Thanks, coach, for sticking with me.’ I think of all the boys, he got the greatest kick out of achieving Stanley Cup eminence in his rookie year.”

For Frank McCool, the end of the 1945 Stanley Cup Final was the end of his Cinderella story. He was slow to come to terms the next season (holding out for a $5,000 contract) and lost his Leafs job when Turk Broda returned from the army late in the schedule. McCool’s name would pop up in rumours for the next few years, but he never played hockey again. He returned to Calgary, where he would work for the Albertan newspaper and serve on many city boards for the rest of his life. McCool was only 54 years old when he passed away on May 20, 1973. His stomach cancer was said to have been related to his lifelong battle with ulcers.