I was 3 1/2 years old when Toronto beat Montreal to win the Stanley Cup in 1967. I don’t remember it. (My hockey memories don’t kick in until after I saw my first game, at Maple Leaf Gardens in December of 1970.) But I remember well when the two teams met in 1978 and 1979. The Leafs of Sittler, McDonald, and Williams, Salming, Turnbull, and Palmateer are the true teams of my youth — and they were good teams too. Still, there was no way they were going to beat the Canadiens back then. Hard to believe its been 42 years!

Plenty of people have been waxing nostalgic recently with this renewal of the Leafs-Canadiens rivalry. So, I figured, why not me? But I’m going back a lot further than I can remember. Further, probably, than anyone can remember even if they were alive at the time. The two oldest franchises in the NHL have met in the playoffs 15 times (the Canadiens lead 8-7) going all the way back to the first Toronto-Montreal NHL series at the end of the first season in league history.

The NHL had four teams when the 1917–18 season started, but just three when it ended. (The Montreal Wanderers withdrew from the league in January of 1918 after fire destroyed the Montreal Arena.) The season was played into two halves, with the Canadiens coming out best in the first half with a 10–4 record. Toronto topped the second-half standings with a record of 5–3. The playoff meeting between the two half-champions was a two-game, total-goals series played on March 11 and March 13, 1918.

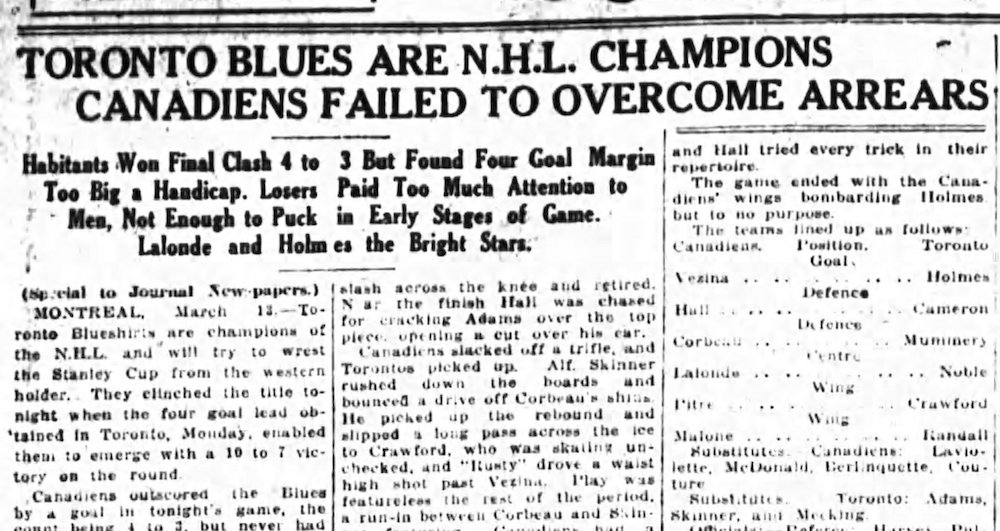

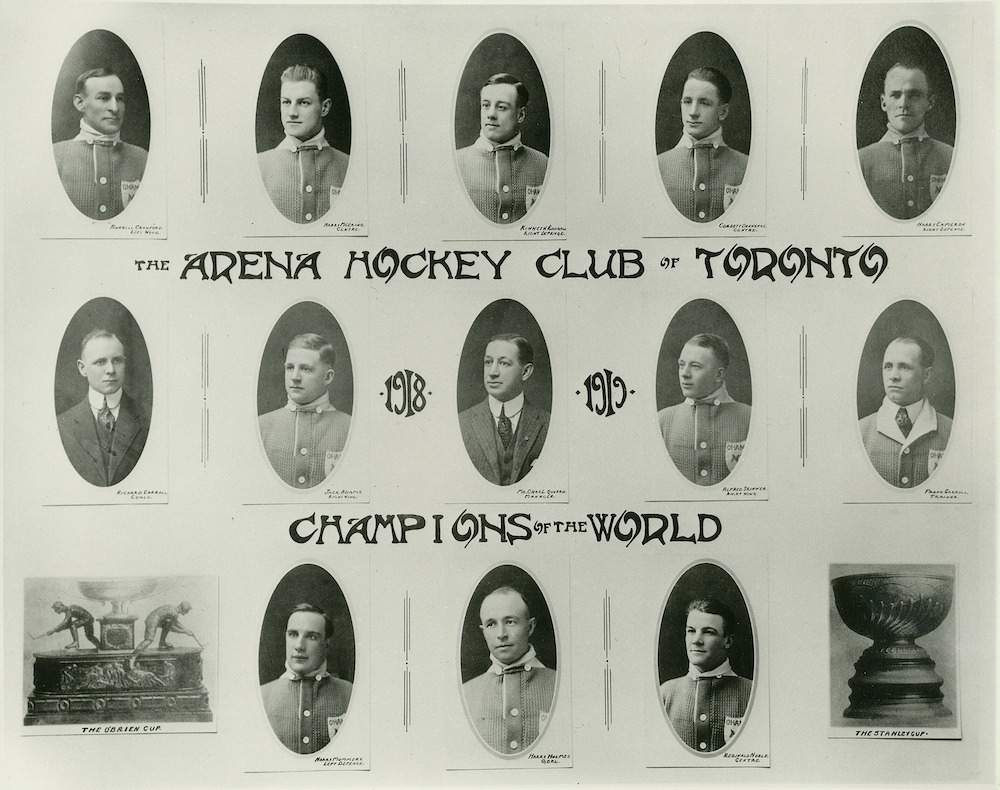

Back in those days, the Canadiens were already known as the Canadiens, as they had been since the team was formed for the inaugural season of the National Hockey Association (forerunner of the NHL) in 1909-10. You can pick a pretty good fight with a hockey historian as to what the Toronto team was called. They’ve gone down in history as the Toronto Arenas, and they were operated that season by the Toronto Arena Company, but probably didn’t take that name officially until the 1918–19 season. The team had been known as the Blue Shirts (two words) or Blueshirts (one word) during its time in the NHA, and most journalists were still using one of those spellings — or referring to them as the Blues, or Torontos — during the 1917–18 NHL season.

as the Torontos and the Blue Shirts (two words).

“The hockey week here opens to-night with the first of the NHL play-off series between Torontos and Canadiens,” reported the Toronto Star on March 11, 1918. “The Blue Shirts, with the exception of Reg Noble, are in excellent shape for the final struggle, and are confident that they will take a three or four-goal lead to Montreal with them for the final game on Wednesday night.”

Another unnamed Star sports writer wasn’t so sure.

“When it comes to a real showdown,” read the column known as Random Notes on Current Sports, “Canadiens are the logical favorites for the NHL championship. They have shown themselves to be a real team – fast, brainy, and game – and many Toronto fans will be back them to win right here to-night.”

But the Toronto players were right. The Blue Shirts/Blueshirts/Arenas won game one by a score of 7–3.

“It is a fortunate thing, indeed, for Les Bons Canadiens that both matches of the NHL play-off series do not take place in Toronto,” said Elmer Ferguson of the Montreal Herald on March 12, 1918. “You’d never know the old club from its play on Toronto ice last night, compared with its dash and brilliance in games played before the friendly faces at Jubilee Rink. And, by the same token, you’d never recognize the meek and inoffensive team wearing the blue shirts which we’ve been accustomed to seeing in the rampaging, aggressive and chip-on-the-shoulder gang which rode roughshod over our habitants last night.”

as the team’s official name: the Toronto Hockey Club.

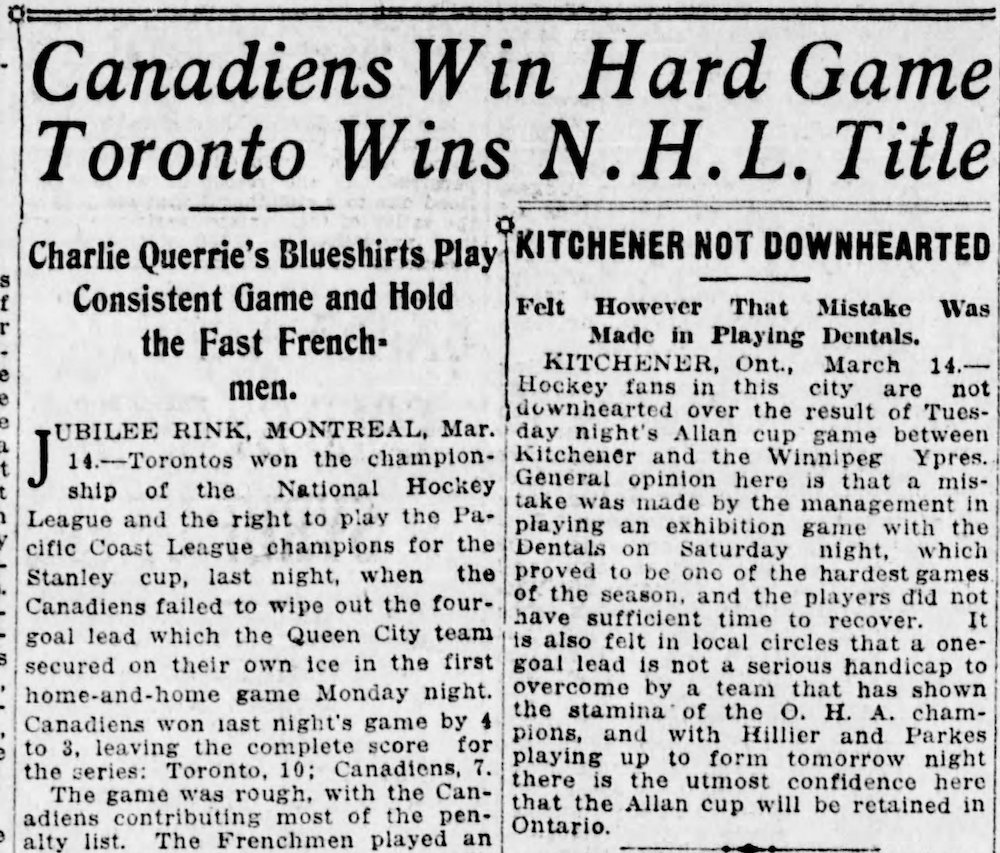

But even with a four-goal lead, hanging on to win the series in Montreal was no sure thing. As it turned out, the Canadiens won game two, but with only a 4–3 victory, so Toronto took the series 10–7 in total.

“The Canadiens chances faded away when they undertook to make the visitors quit by roughing it on every possible occasion” reported the Montreal Gazette on March 14. “Canadiens suffered through penalties… Toronto played the puck more than the man, and took the bumps handed out to them without retaliating to any great extent. This counted greatly in their favor.”

NHL summaries show that far more penalties were called in game one at Toronto. Even so, game two in Montreal must have been rougher.

“Bullfighting is prohibited in Canada for the reason that it is considered brutal,” wrote Harvey Sproule (a future Toronto NHL head coach, briefly, in 1919–20) in the Toronto Star, “but it is a regular ‘pink tea’ in comparison with the Donnybrook served up to the fans at the Jubilee Ice Palace last night…”

but it’s clearly been dated for the 1918–19 NHL season.

With the win Toronto took the NHL championship, but not yet the Stanley Cup. Winning the NHL title that season only entitled the Blue Shirts/Blueshirts/Arenas to host the Pacific Coast Hockey Association champion Vancouver Maroons (who wore maroon-coloured shirts) in a best-of-five Stanley Cup Final. Toronto won that series 3-games-to-2 with a 2-1 victory in the finalé on March 30, 1918 to claim what was already a prized trophy.

And this year?

I think Toronto is good enough to win in four games, but probably five. Then again, if Leafs goalie Jack Campbell can’t carry the playoff weight, and the Canadiens’ Carey Price can turn back the clock … well, let’s just say I wouldn’t want to trust Freddie Andersen in another seventh game!