The Toronto Maple Leafs have certainly been a much more entertaining team to watch this season. Still, with two games to go before a four-day break over Christmas, they currently sit in last place in the Atlantic Division – although only six points out of third place, which would net them a playoff spot.

While it wouldn’t be impossible, I don’t believe they’ll make the playoffs this year. Even so, with rookies Auston Matthews and Mitch Marner, plus William Nylander and several others, Leafs fans seem satisfied that the plan in place of building patiently through the NHL Draft is already showing positive results.

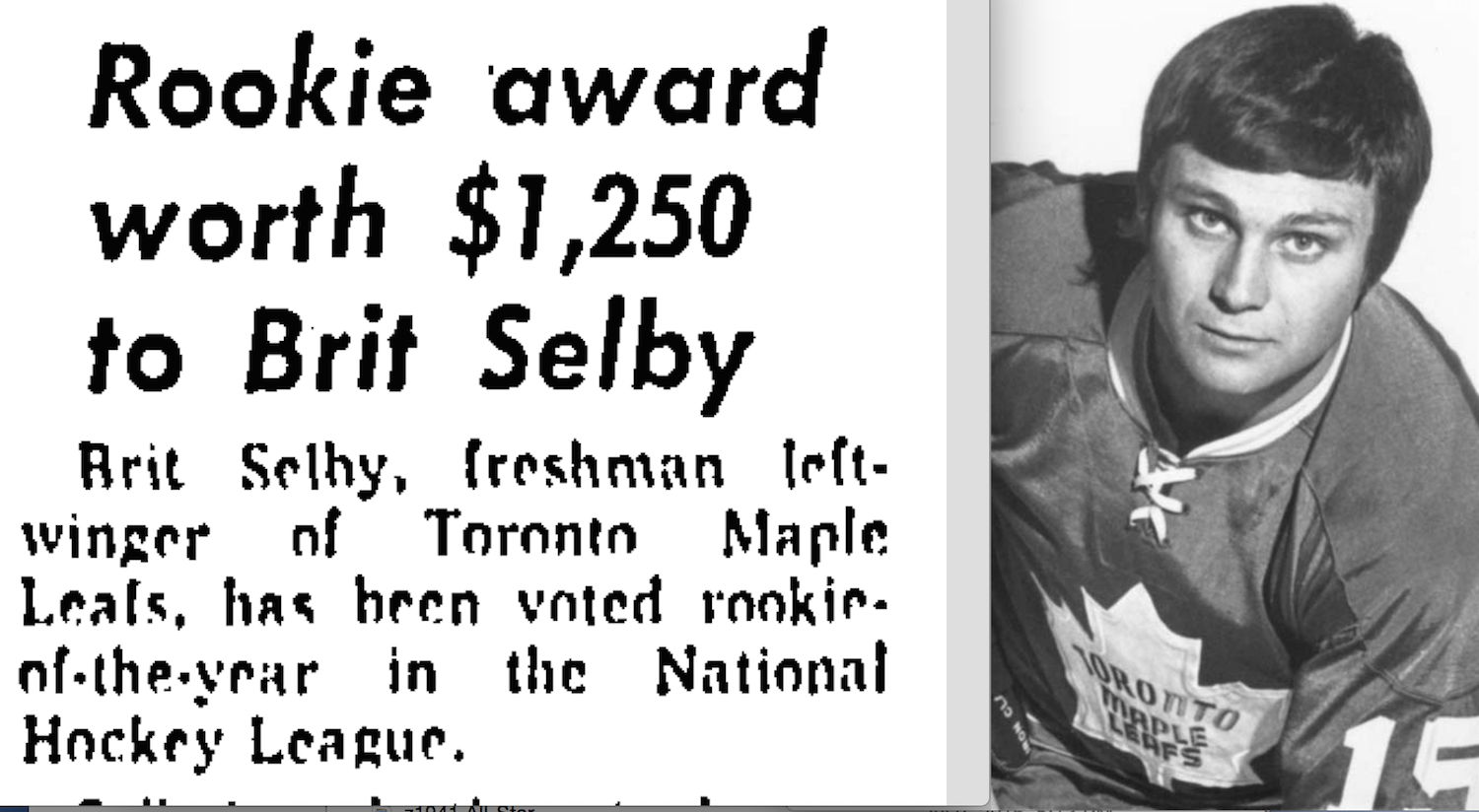

Brit Selby was the last Maple Leaf to be named rookie of the year back in 1965-66.

With Matthews turning 19 just a month before the start of the season, and Marner not turning 20 until May, these two may well be the most promising pair of teenagers to join the team together since 19-year-old Charlie Conacher and 18-year-old Busher Jackson way back in 1929-30. Matthews is on pace to break the Maple Leafs rookie record of 34 goals, set by Wendel Clark as a 19-year-old (and #1 overall draft pick, like Matthews this year) back in 1985-86. Yet like Wendel, who finished second in Calder Trophy voting behind Gary Suter that season, Matthews is certainly no shoo-in as the NHL’s rookie of the year. Patrick Laine is currently outscoring him in Winnipeg, and rookie defenseman Zach Werenski has been impressive as well for the surprising Columbus Blue Jackets.

There was not yet a Calder Trophy for rookie of the year when Charlie Conacher and Busher Jackson broke into the NHL. Conacher led all NHL newcomers with 20 goals in just 38 games played that season. That may have won for him, if there’d been a reward, but the best newcomer during that season was probably Detroit’s future Hall of Famer Ebbie Goodfellow. He played the full 44-game schedule and had 17 goals and 17 assists to top all rookies with 34 points.

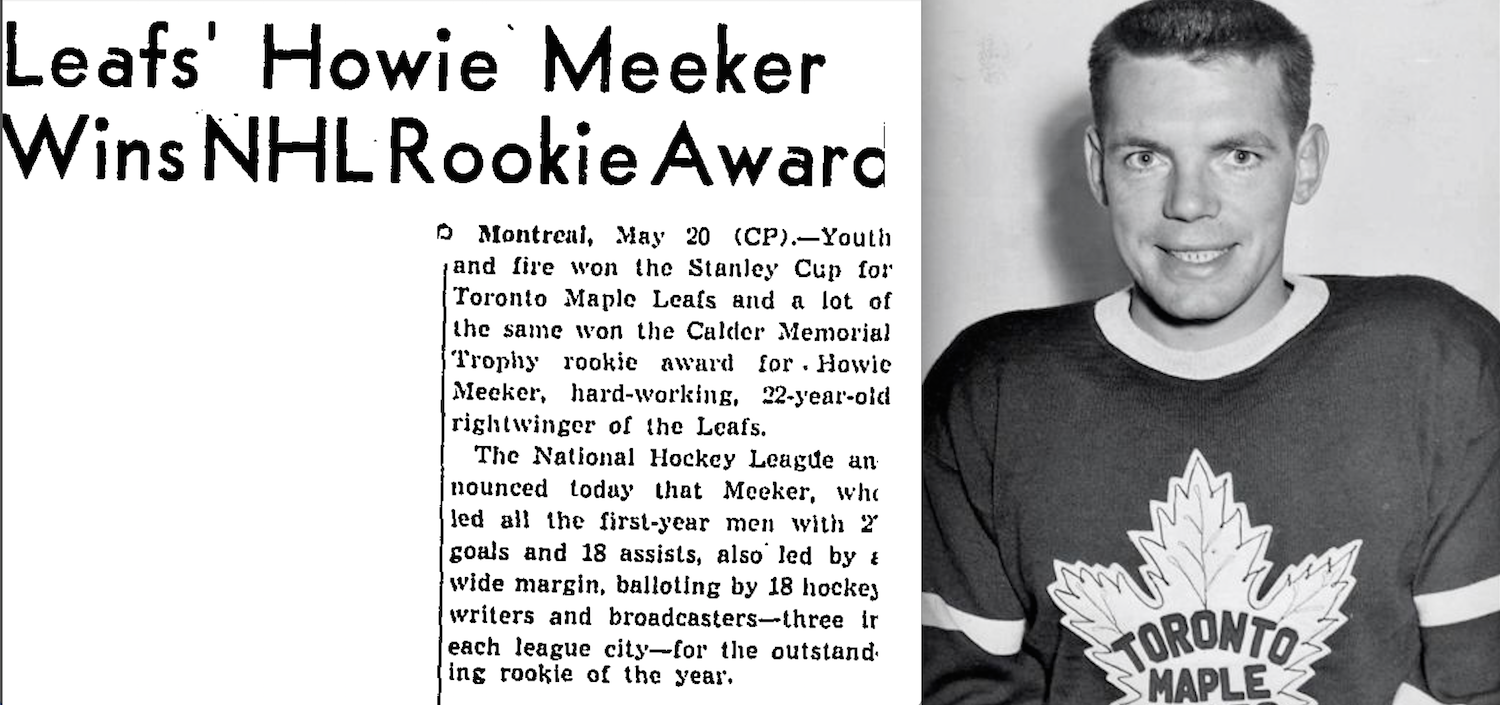

Howie Meeker was top rookie in 1946-47, but didn’t get all that he should have for it.

Though it’s not talked about nearly as much (for obvious reasons!), Toronto’s Calder Trophy drought is even longer than its Stanley Cup drought. This season marks 50 years since Toronto’s last championship in 1967, but 51 years since Brit Selby was named rookie of the year in 1965-66.

Selby had just 14 goals and 13 assists in 61 games as a Leafs rookie in 1965-66, but comfortably outpointed Bert Marshall and Gilles Marotte (98-90-68) in Calder Trophy voting that year. Clearly, though, the best rookie in the long run from that season would turn out to be goalie Bernie Parent, who finished fourth in the voting with 69 points.

Frank McCool was a wartime replacement who battled debilitating ulcers.

After helping Toronto win the Stanley Cup as a rookie in 1944-45,

he was out of hockey by the end of 1945-46.

Selby, and Kent Douglas, who won the Calder for Toronto in 1963, hardly went on to superstars careers – although Dave Keon, who won it in 1961, certainly did. All in all, through the years, most of the NHL’s rookies of the year have gone on to be fine players. Many have gone on to Hall of Fame careers. But there are some quirks. Frank Mahovlich beat out Bobby Hull for the Calder in 1958, and though both went on to stellar careers, it’s hard to argue that Hull wasn’t the better player in the long run. Back in 1946-47 (when the Leafs underwent a similar youth movement to what we’re seeing this year,) Howie Meeker was clearly the NHL’s best rookie and was deservedly rewarded with the Calder Trophy – as he should have been. Yet who could disagree that a kid in Detroit by the name of Gordie Howe went on to become the better player!

According to Meeker, who tells the story in his own book, Golly Gee, It’s Me and told it to author Greg Oliver for his book, Written in Blue and White, Leafs owner Conn Smythe had promised him a $1,000 bonus if he won a league trophy in his rookie season. Oliver points out that there is no such clause in the contract, but Meeker tells him that “[Smythe] told me verbally twice, and we shook hands on the deal.”

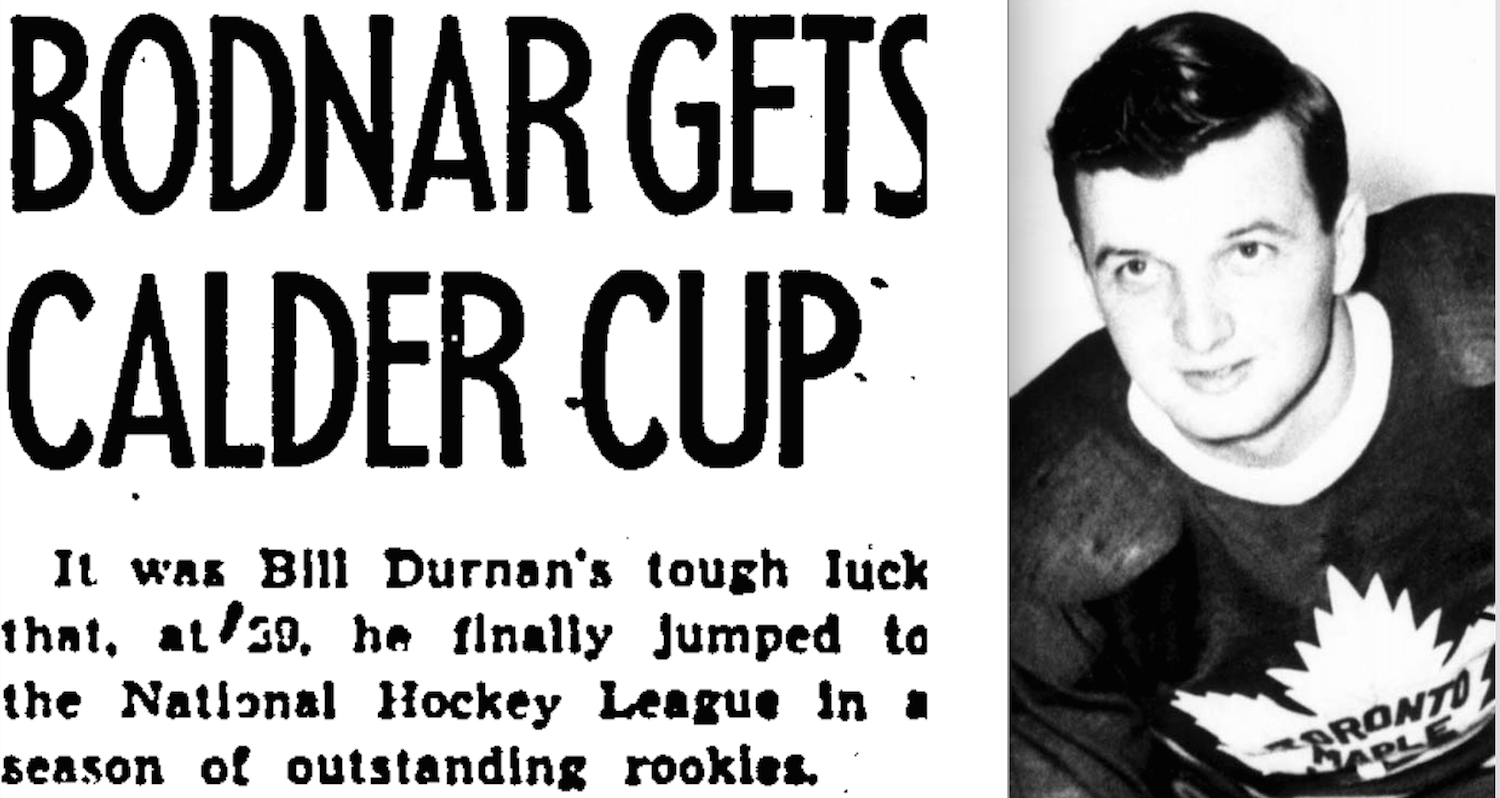

Gus Bodnar’s goal 15 seconds into his first game on October 30, 1943, is still an

NHL record for the fastest goal by a player in his NHL debut. He had a

career high 22 goals and 40 assists as a rookie, but was still a surprise winner

of the Calder Trophy over Montreal goalie Bill Durnan.

When he won the Calder Trophy, the Globe and Mail noted: “Meeker also collected a $1,000 bonus, given by the NHL for the first time this year. The bonus will be matched by another $1,000 from Maple Leaf Gardens.” So, clearly, more than just Meeker and Smythe were aware of the promise, and yet Meeker never got his money. As he told Oliver: “When the time came around, [Smythe’s] excuse was ‘You got $1,000, but it was from the NHL.’” Meeker wasn’t happy! “I was pissed off for a long time,” he told Oliver.

At the time, Meeker was the fourth Toronto Maple Leafs player to win the Calder Trophy in five seasons, following up on three straight wins by Gaye Stewart (1943), Gus Bodnar (1944) and Frank McCool (1945).

Syl Apps was recently named #2 all-time among the Leafs’ top 100 players,

behind 1961 Calder Trophy winner Dave Keon.

Still the strongest season in history for Leafs freshmen was likely 1936-37. This was the first year in which NHL president Frank Calder provided a trophy for the league’s best rookie and Toronto players finished 1-2 in the voting. Syl Apps, having finished just one point back of Sweeney Schriner for the NHL scoring title, won the Calder Trophy. Gordie Drillon (who would win the scoring title the following year – the last Leaf ever to do so!) finished second. And if you don’t recognize the name of that guy who finished sixth in the Calder voting that year, it might be because you know him better as Turk Broda.