My web site recently turned five years old. I posted my first story on October 10, 2014. Seems hard to believe. The intention at the time was to promote my writing and to try and drum up more appearances for me at schools to talk about my kids books. It was NOT to help me work through my problems.

That said, a lot of you have only been reading my site since I started posting stories about Barbara and me. Even for those who’ve followed me since the beginning, I’ve certainly gotten more reaction from these personal stories than anything else … and it helped me. A lot. So, thank you. Still, I’m not one who really likes to talk about his feelings! When I had something to say (or something to work through) I wrote about it. But I haven’t felt the need for a while. I guess that’s good.

When my web site was first set up, I told people that I would use the News and Views section to “share some of the quirky sports history stories I come across during my research.” It was fun for me, so I pretty much shared something every week. But I haven’t had much cause to be poking through old hockey stories lately. Nor much inclination, either. The truth is, the only real lingering side effect that I can detect in myself after 14 months is that I don’t have much enthusiasm for work. That might be a function of aging as much as anything. I don’t know. But even when I’ve had work, and I’ve gotten into it – and expected that would make doing more work easier – I still wake up the next day thinking, “I have to do it again?!?”

Well, I may not like working, but I do like to eat … so early this past summer, I agreed to do a book about football for National Geographic Kids. (Mainly American football, but I slide in the occasional Canadian reference when I can.) The book will be very similar to many of the hockey books I’ve done in the past, but I have to admit it’s been kind of fun to be researching something different. (As it was several years ago when I did a soccer book for NGK.) This one’s going a little slower than I’d like, but I’ll still have it ready for them on deadline at the end of this month. And, recently, while working on it, I came across the kind of story that I love to dig into. So, I thought I’d share it.

The football book is part of a series of Sports by Numbers, so it needs to include as many numbers as it can. Math when possible, but statistical lists are more than acceptable. So, plenty of those. And when delving into the longest field goals in football history (NFL, CFL, NCAA, anything!), I stumbled across the fact that a man named John Triplett “Jerry” Haxall had kicked a 65-yard field goal for Princeton versus Yale … in 1882!

Given how large and heavy a football of that era would have been, this struck me as pretty much impossible! I had to know more.

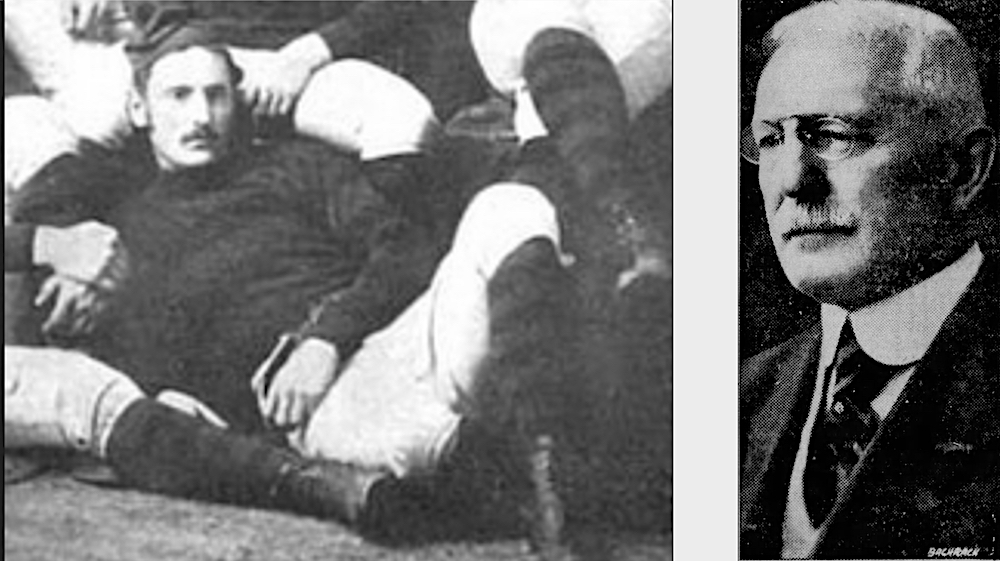

Fortunately, Wikipedia has a short entry on Haxall. He was from a wealthy Virginia family and later went on to a long and successful career in banking in Baltimore. Not that Wikipedia tells you much about that. But it did have a reference to a story by legendary sportswriter Grantland Rice on November 30, 1915 that proved a fine starting point.

As it turned out, on October 16, 1915, a player named Mark Payne at Dakota Wesleyan University had drop kicked a field goal from 63 yards out, breaking the 1898 drop-kick record of 62 yards by P.J. O’Dea of Wisconsin (both of which also strike me as impossible!) This put Haxall’s 65-yard place kick — which had been noted year in and year out in the Spalding Football Guide – back in the news. And (like me, now) there were people who doubted it.

Apparently, Grantland Rice asked to hear from anyone who’d been at the game and could testify to Haxall’s record. He got a response from James O. Lincoln, Yale class of 1884. “Dear Sir,” wrote Lincoln. “Luther Price, a newspaper man whom I know well, is correct. Haxall kicked that goal against Yale in 1882. I saw him perform the feat. Although, of course, the spectators did not measure the distance, it was beyond the midfield, and was announced at the time as being sixty-five yards.”

This satisfied Grantland Rice … but I was still skeptical. So, I began looking for contemporary accounts of the game played at New York City’s old Polo Grounds. In reporting on it, the Boston Globe on December 1, 1882, said only that, “This was the greatest kick ever seen.” The New York Sun said, “It was a long distance, and nobody believed that he could make it.” However, the Sun also said the ball “was 115 feet from the goal.” That’s only 38 yards or so, and, apparently, it was this account that led people in 1915 to wonder. But the New York Times (who wrote Haxall’s name as Hoxall) had said in its game report, “He was over 65 yards from Yale’s goal,” and the Hartford Courant (which spelled his name as Hachall) said he “sent the ball 66 yards across the field to the goal.”

But I was still curious, so I kept digging…

Next, I found a story from December 12, 1915, which quotes Parke H. Davis writing a few days before in the New York Herald. “Since I am the compiler of this record,” wrote Davis of his work for the Spalding Guide, “I beg the privilege of defending its accuracy… My authorities for fixing the distance of this field goal at sixty-five yards are the accounts in the Yale News, the periodicals at Princeton, and the testimony of several eyewitnesses of the kick.”

The Yale News of December 5, 1882, quoted by Davis, says that the Yale team knew to look out for Haxall, and that he was 65 yards from the Yale goal, “when he made a kick that would have disturbed the transit of Venus. Slowly, steadily the ball was blown onward by the wind over the heads of the breathless players to drop at last on the wrong side of the goal for Yale. And now pandemonium reigned among the yellow and black. It is said that this is the finest kick ever made. You should erect a bronze statue of Haxall, Princeton.”

As to the players Davis interviewed, many had gone on to be prominent business men. “The members of these football pioneers are strikingly clear as to the events of the game, he says. “While no one of them says positively that the goal was kicked down sixty-five yards, in the absence of any mark except the midfield mark, which was fifty-five yards distant from the goal [NOTE: American fields were not reduced to the 100-yard standard of today until 1912, while Canadian football fields have remained 110-yards long], all of these players, nevertheless, assert that the kick was ‘about sixty-five yards.’”

It’s interesting to note that the Princeton narration of the game says only that “Haxall kicked (a) magnificent goal from midfield among Princeton cheers.” Yet Davis then quotes a player from that game who’d become a well-known clergyman in New York … though he chooses not to mention him by name: “Haxall put the ball down for a place kick fully 65 yards from the goal line,” states the clergyman at the end of a lengthy recollection of the game, “and what is more he stood at least 15 yards towards the one side line from the center of the field, thereby not only making the kick more difficult but in reality making the kick longer than 65 yards. The ball sailed in the wind squarely between the posts.”

Not surprisingly, all the talk of his 33-year-old field goal record came to the attention of J. Triplett Haxall himself. He was then asked by a fellow Prinecton alum to give his account of the kick, which he did for the Princeton Alumni Weekly in mid December of 1915.

Haxall writes that he and Tommy Baker (apparently an uncle of U.S. hockey legend Hobey Baker) had practiced their kicking “for some time preceding the Yale game of 1882.” They discovered that having the holder place the ball practically perpendicular to the ground and then kicking it on the bottom end, “started it accurately revolving on its long axis and resulted in long distance being realized before it began to drop.” Haxall added, “why the tendency nowadays seems to be to kick the ball in its middle and not on its ends I have never been able to understand.” (I guess kickers eventually rediscovered Haxall’s technique.)

As for the big kick in the Yale game – which Princeton lost, by the way: “I have always understood the distance was as recorded by the officials who had such matters in hand. The claim lately advanced that, due to a typographical error, the distance should have been 35 yards and not 65 yards, I think all the writings of the time sufficiently refute.”

Haxall recalls, “the wind was blowing sufficiently to require testing its direction by tossing up a bunch of grass or something of the kind,” but states that his record kick, “was the result of quite long practice by Tommy Baker and myself.”

Following his death on June 5, 1939, an obituary in the Princeton Alumi Weekly from July 7, 1939 (which is quoted on Wikipedia), notes that Haxall had once remarked, “My epitaph will probably be:

J.T. Haxall

Kicked a football.

That’s all.

Well, he did get a larger writeup in the Baltimore Sun, but he wasn’t far off.

It still may not be 100 percent official, but if it wasn’t for that lengthy kick, who’d still be writing about John Triplett Haxall today?