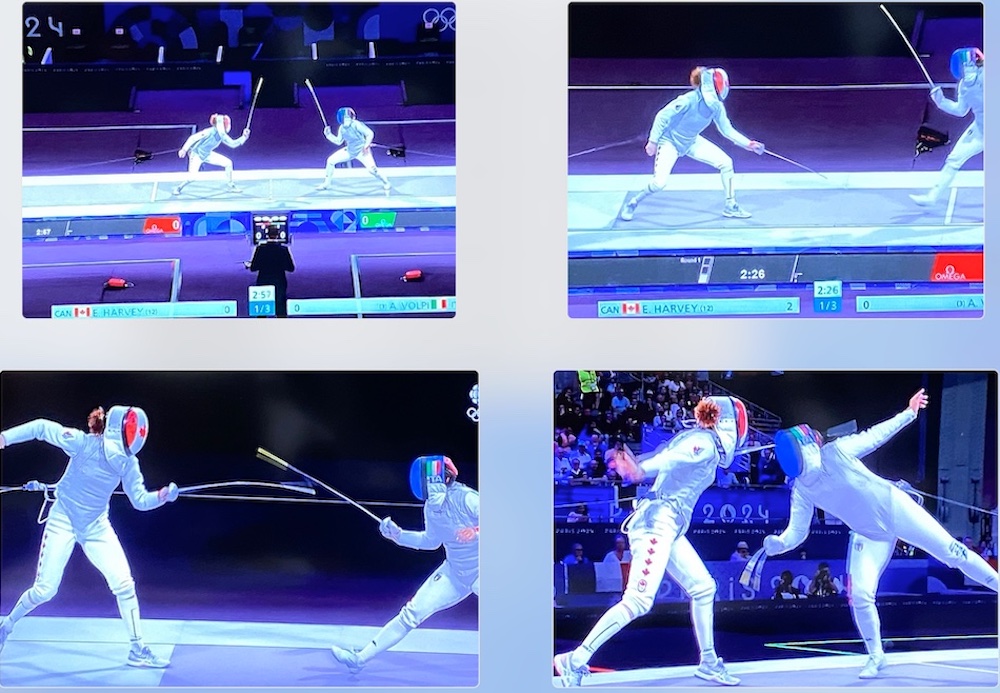

I’m sure it won’t surprise anyone to learn I’m watching plenty of Olympics. Not a ton, but still plenty. Watching sports I don’t usually watch, like fencing, where Eleanor Harvey won a bronze medal for Canada in Women’s Individual Foil…

And Women’s Rugby Sevens, where Canadian women earned a silver. Canada had a chance, but I think the better team – New Zealand – won. The game was exciting, but it’s always a bit strange to “lose” the silver medal…

Part of the enjoyment of these Olympics for me is that Lynn and I were in Paris in May (my first time), and it’s been fun to see some of the sites we just recently saw.

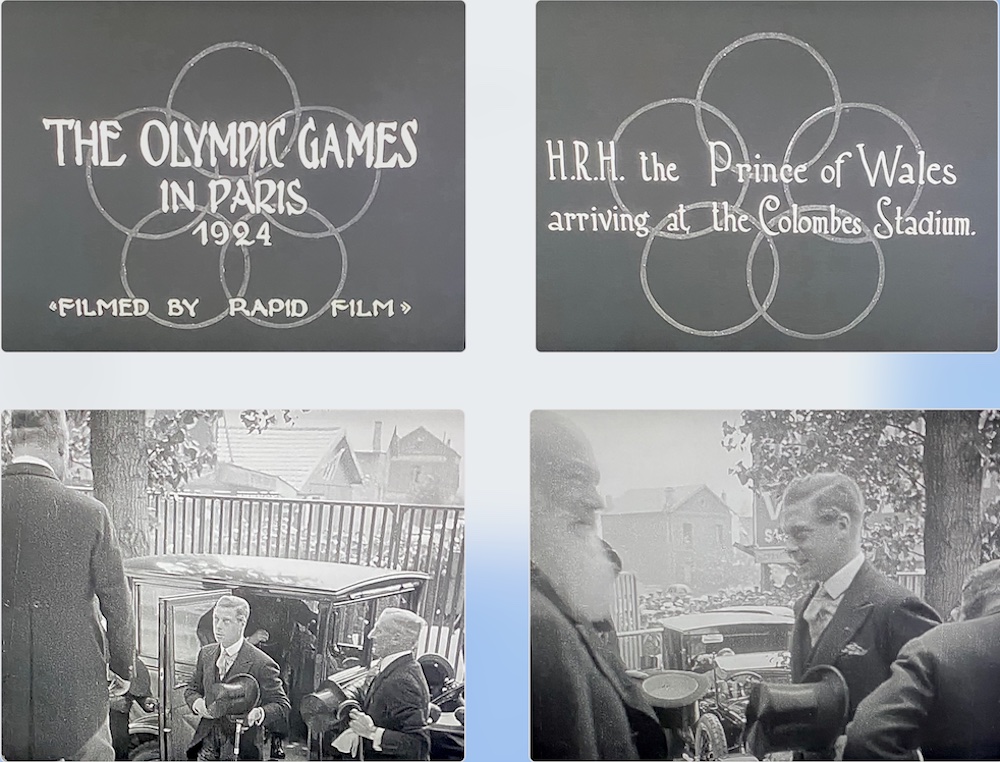

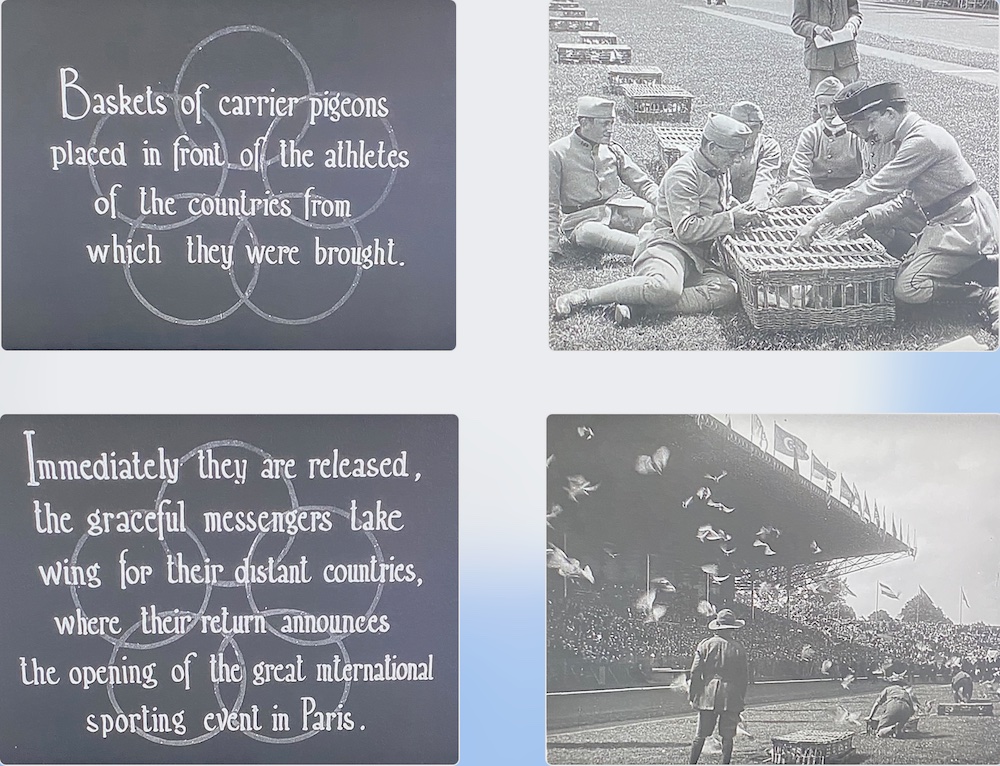

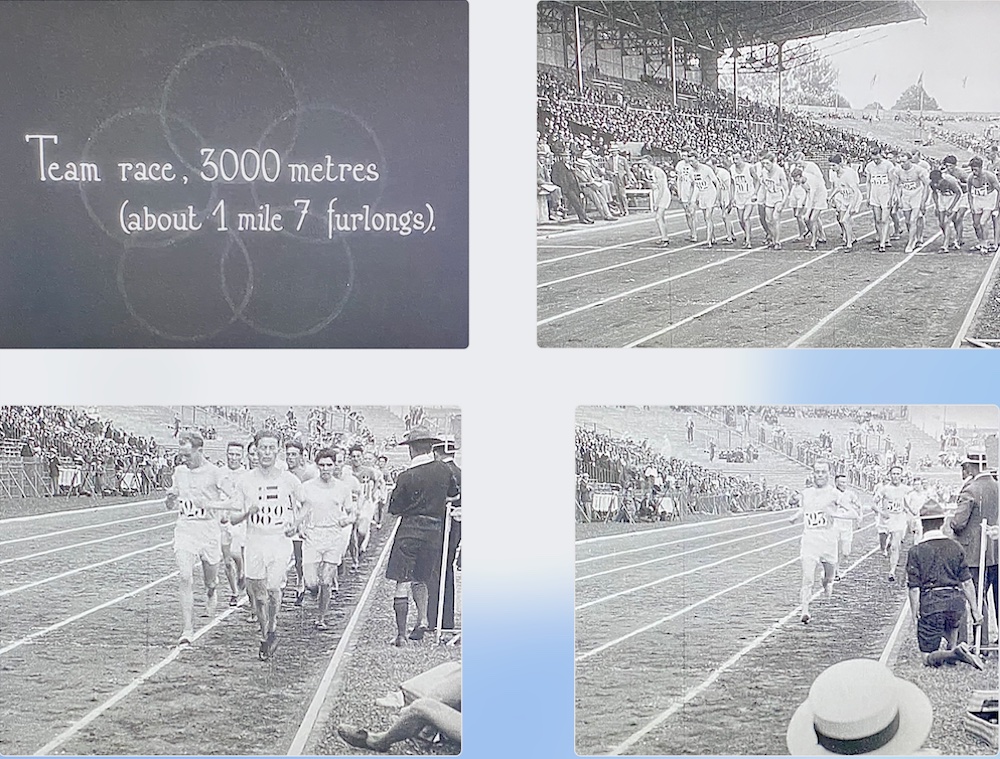

But, so far, Olympic-wise, I think I’ve had even more fun watching the film of the 1924 Paris Summer Games, which was reconstructed from French and British archives. (It was one of several official Olympic films that aired on Turner Classic Movies the night the 2024 Paris Olympics opened.) The film is, of course, black and white. It’s silent too, with title cards. Running time is nearly 3 hours, and while I admit I watched plenty of it on fast-forward, it’s pretty fascinating stuff! So, I hope you’ll enjoy the little still-image synposis that follows.

The opening shots set the scene with footage from the Opening Ceremony on July 5, 1924:

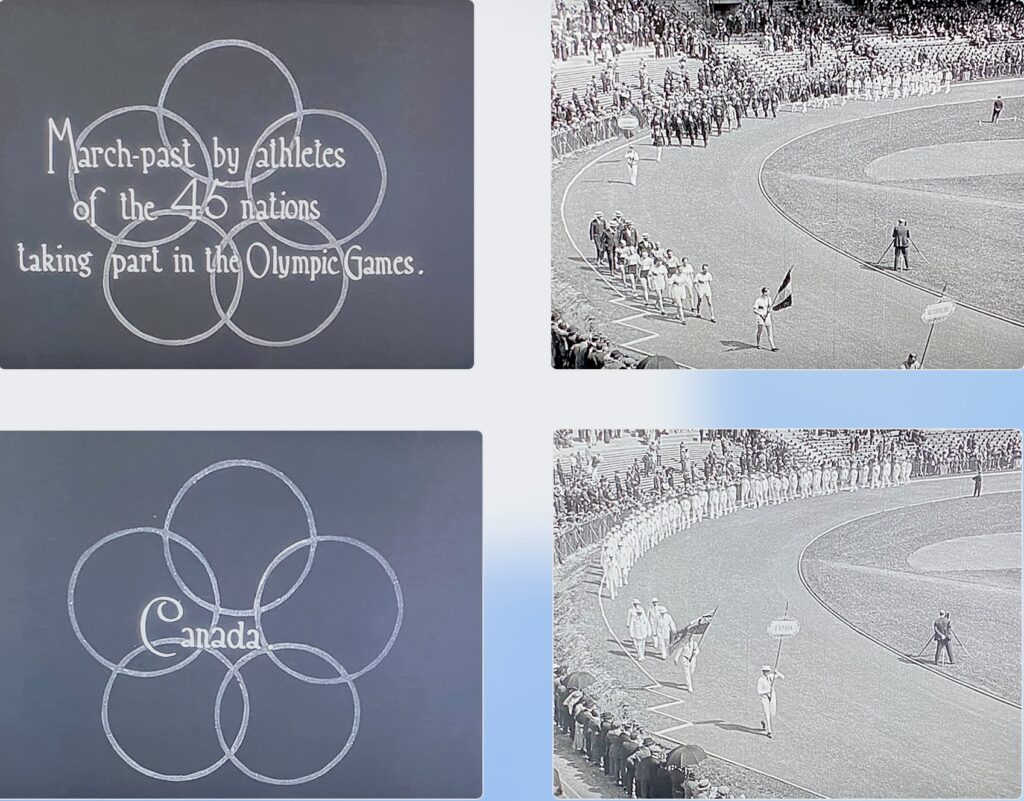

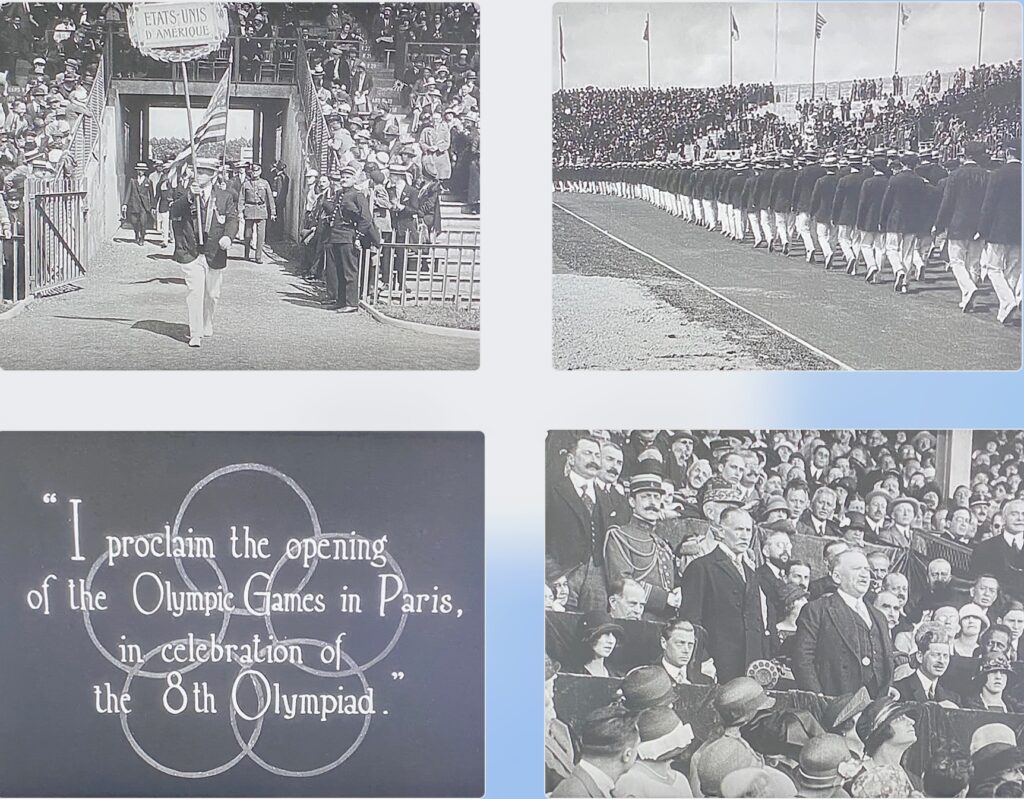

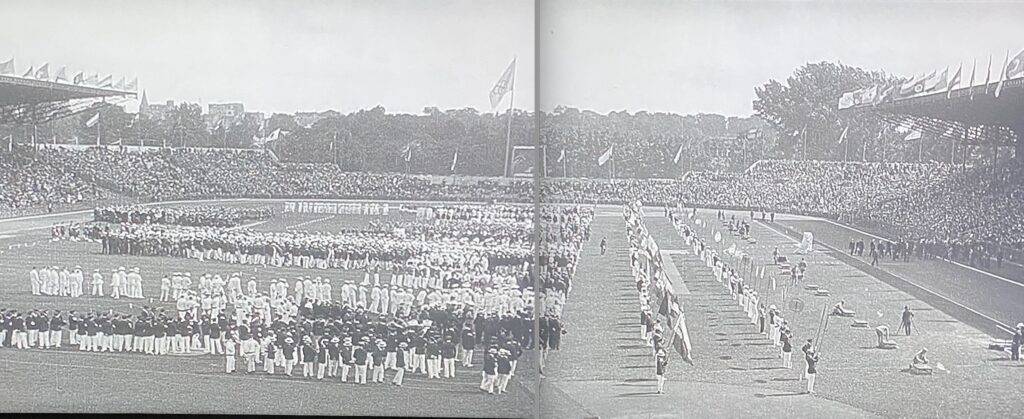

We then move inside for the parade of athletes. The first title card you’ll see mentions 45 nations, though most web sites seem to say there were only 44. Wikipedia lists 3,089 athletes, of which 2,954 were men and 135 were women. Female athletes competed only in swimming, diving, fencing, and tennis. They were not permitted to compete in track and field events until the 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam.

France, as the host nation, had the biggest team in 1924 with 401 athletes. The Americans were next with 299.

I combined two images into one here to give a sort of panoramic look at the Olympic Stadium, which, by the way, is still in use in Paris and will host the field hockey tournament this year.

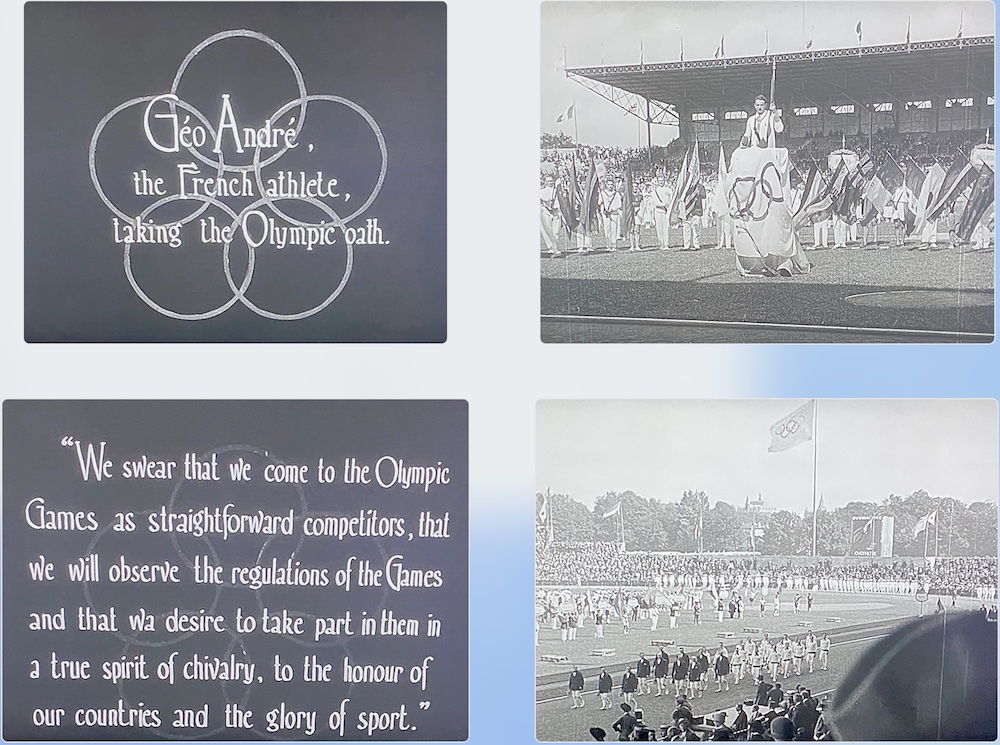

The tradition of the Olympic oath began at the Antwerp Games in 1920 and continued in Paris in 1924. The text, originally written by Pierre de Coubertin, has evolved. Since the 2000 Games in Sydney, it has included a sentence committing to sport without doping. These days, as well as on behalf of the athletes, the Olympic oath is taken on behalf of the officials and coaches. (Way to go, Canadian soccer officials!)

There were 126 events in 23 disciplines, comprising 17 sports, on the Olympic program in 1924. The full film shows most (but not all) of them. This little “slide” display will concentrate mostly on the famous athletes who took part, and mostly just in track and field, AKA Athletics:

Paavo Nurmi of Finland was the biggest star of 1924 Games. I probably first heard of him in the lead up to the Montreal Olympics in 1976, as I know our family bought a couple of books about those Games and the history of the Olympics that year. “The Flying Finn,” as he was known, ran with a stopwatch to help him control his pace. (You can see him checking his stopwatch in the third image.) A middle and long distance runner, Nurmi had already won three golds and a silver medal at the 1920 Olymics, and would add another gold and three more silvers in 1928. In Paris in 1924, he won gold in five different events: the 1,500 meters; 5,000 meters; Individual Cross Country, Team Cross Country, and Team 3,000 meters. That’s Nurmi approaching the finish line in the last image.

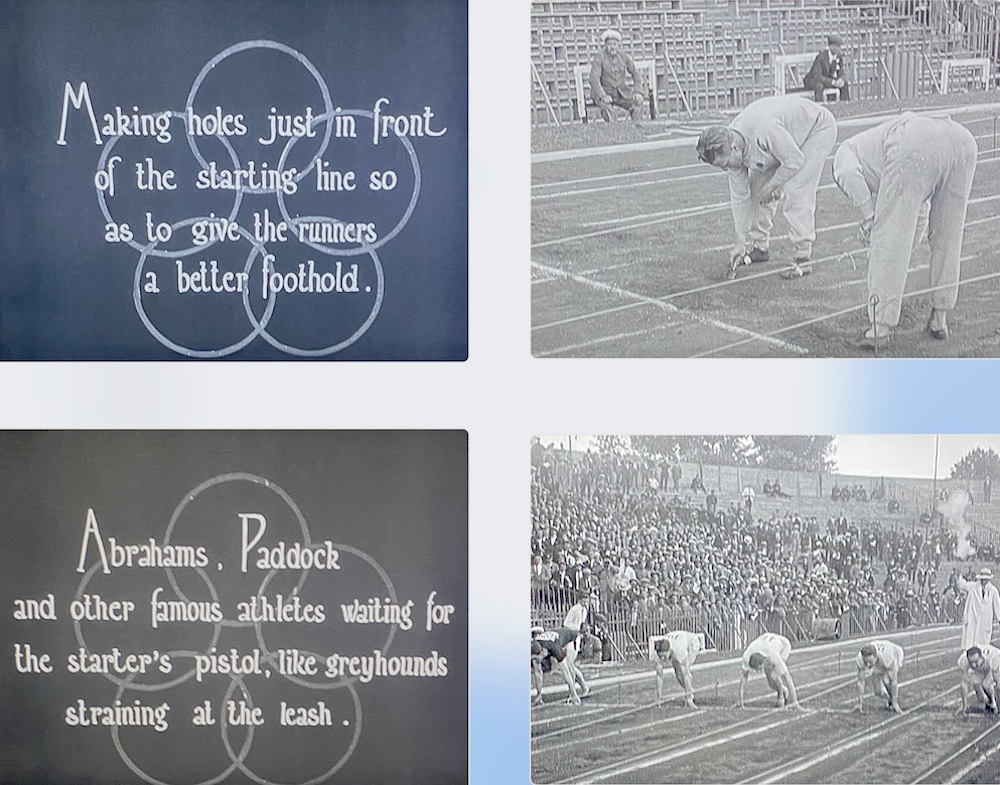

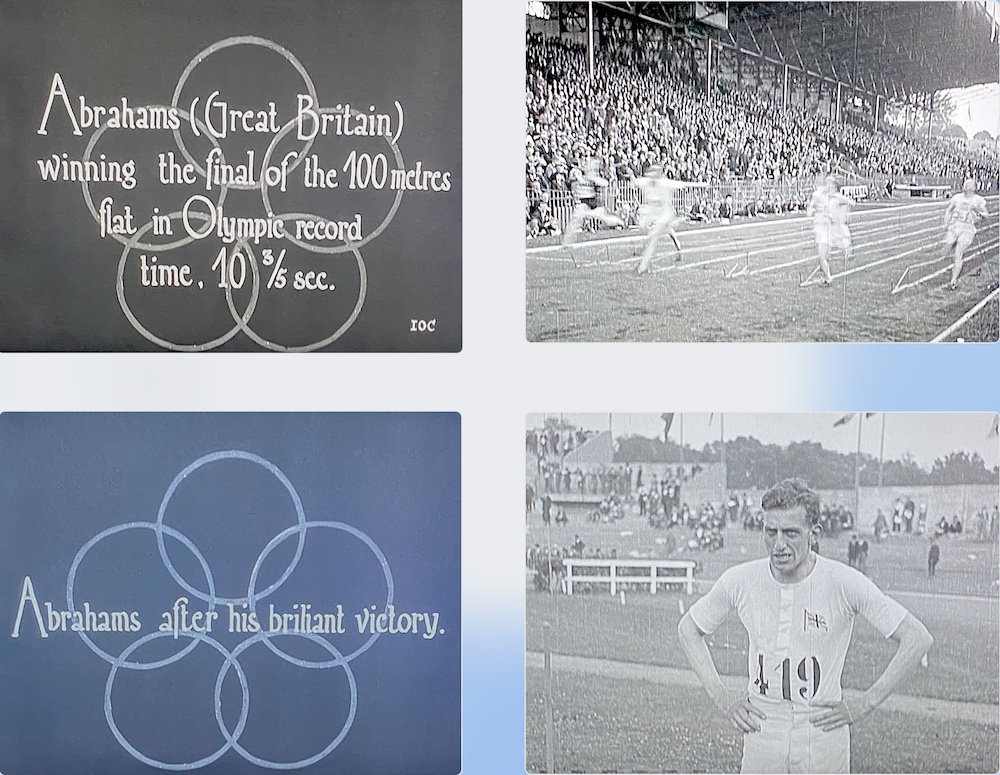

Track and field at the 1924 Olympics featured two British runners made famous (again) in the 1981 film Chariots of Fire. One of them was Harold Abrahams, who won the 100 meters in an upset of 1920 Olympic champion Charley Paddock of the United States. Abrahams was an amateur athlete who controversially employed a professional coach. His father was a Jewish immigrant to England from Polish Lithuania, which was then part of the Russian Empire. Abrahams also won a silver medal in the 4 x 100 relay in 1924.

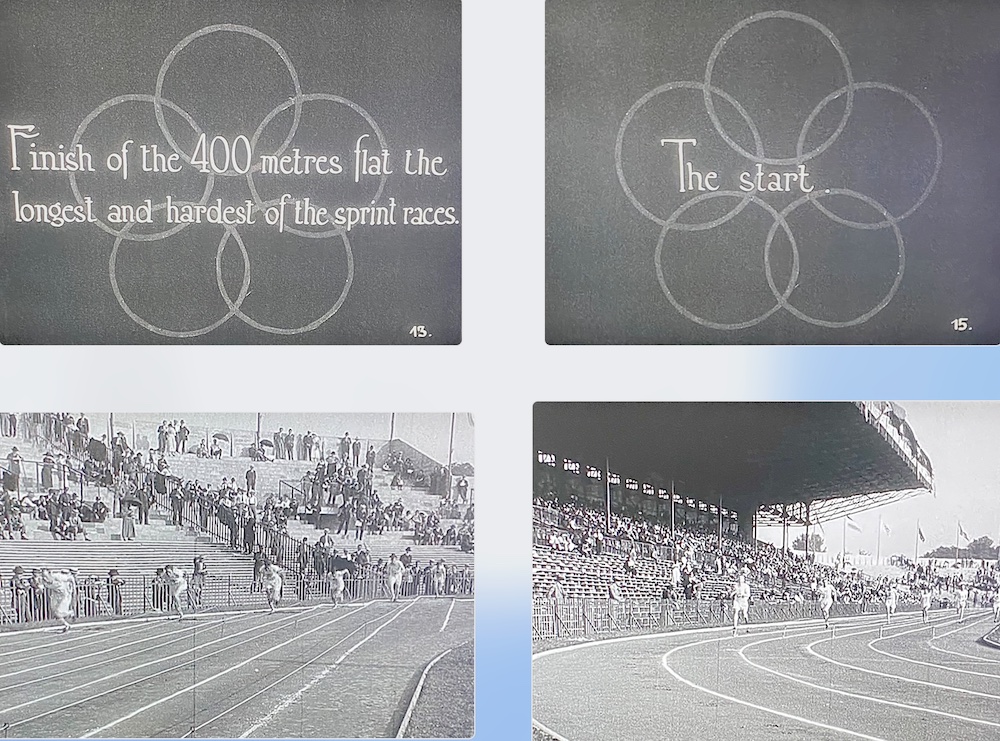

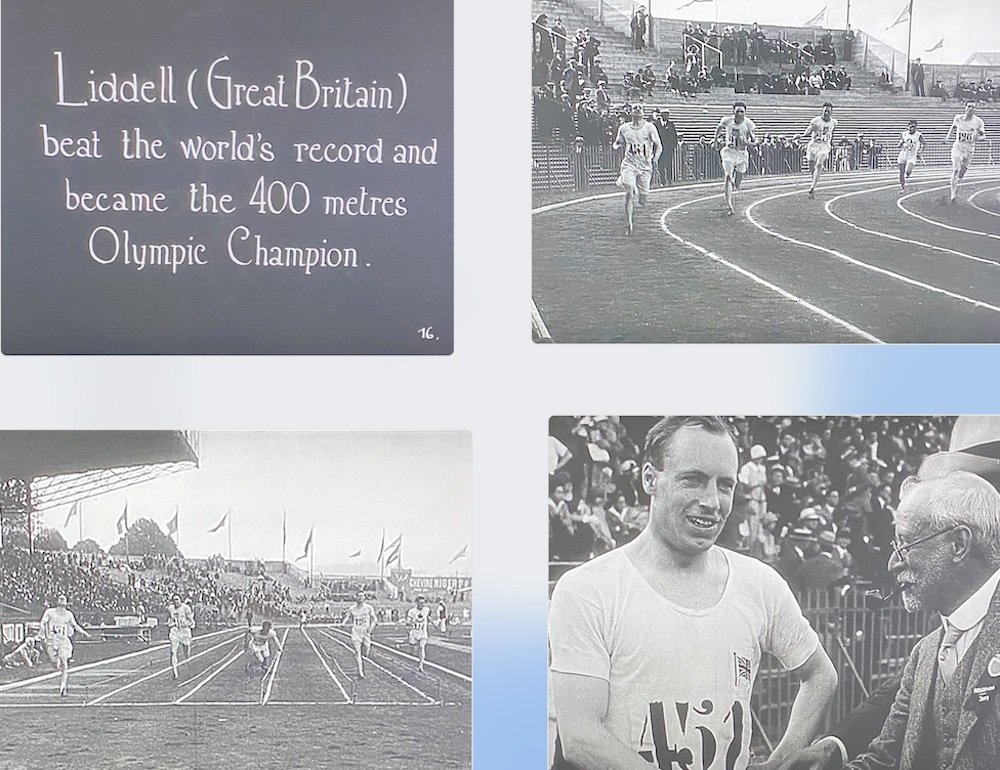

Eric Lidell was a devout Christian, born in China to Scottish missionary parents. He refused to compete in the 100 meters at the 1924 Olympics because the preliminary heats were held on a Sunday, and he did not run on the Sabbath. Lidell later won the 400 meters and earned a silver medal in the 200 (in which Abrahams finished sixth).

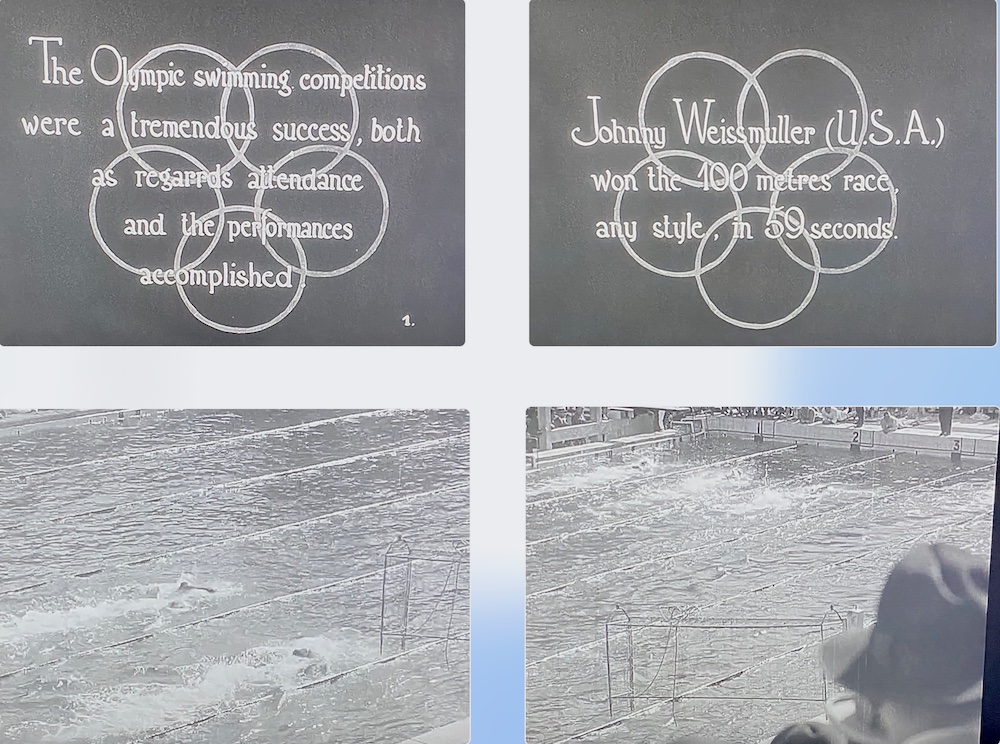

Perhaps the most famous athlete to compete at the 1924 Paris Olympics was American swimmer Johnny Weissmuller. Weissmuller won gold in the 100, 200 and 4×200 meter freestyle events, and earned a bronze medal with the U.S. water polo team. He’d win gold in the 100 meters and the 4 x 200 in Amsterdam in 1928, but is probably best known for playing Tarzan in 12 movies between 1932 and 1948 after his retirement from competitive swimming. There are no individual shots of Weissmuller in the 1924 Olympic film, but that’s him out in front in lane four in the third picture, and you can see his “wake” at the finish well in front of the swimmers in lanes one, two, and three in the fourth shot.

There’s tons more great footage in the film from most of the other sports. Notably for me was the high jump and pole vaulting, whose competitors look even more ancient in comparison to today’s athletes that do the sprinters. Diving too. Barely a twist or a tumble. It looks like a well-executed cannonball from the high tower could have won! There’s also soccer, rugby, fencing, yachting, rowing, canoeing and tennis. Perhaps I’ll add some of that later during the Olympics, but perhaps not. (Putting this together was way more labour-intensive than I’d imagined!) But, I’ll conclude today with this:

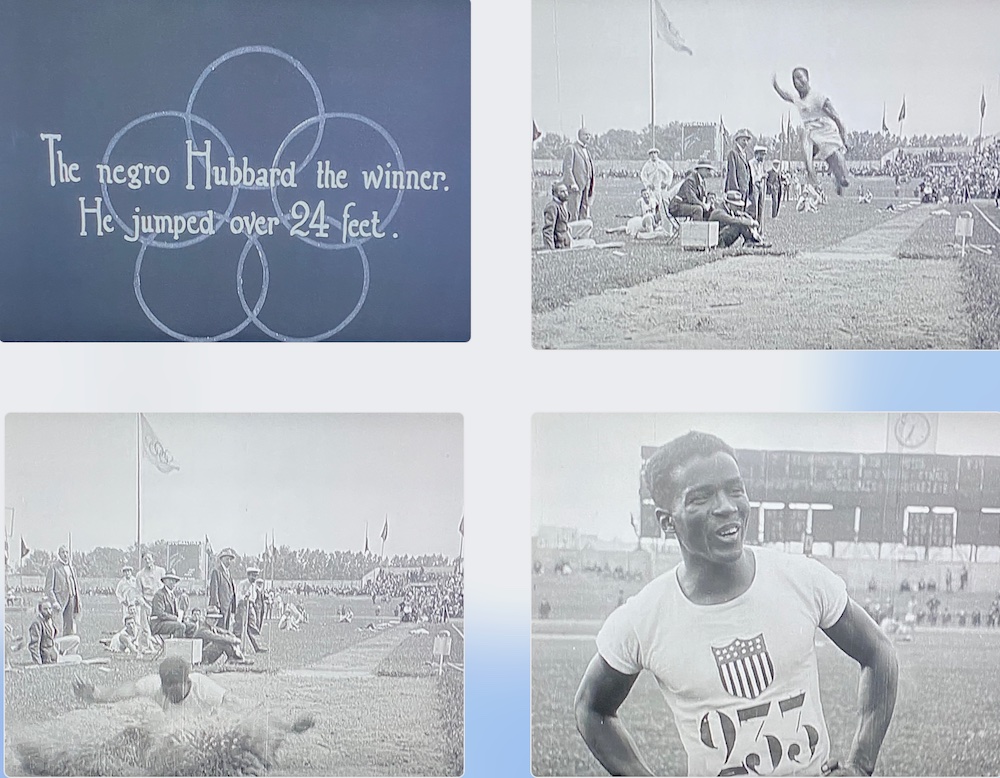

There were hardly any Black athletes to be seen in the 1924 Olympic footage. Hardly any athletes of any colour but white. William DeBart Hubbard is not someone I’d heard of previoulsy, but he became the first African-American to win a gold medal with his victory in the long jump in 1924.

Wikipedia reports that DeBart Hubbard qualified for the Olympics in the broad jump and the triple jump. It also references an NBC News story from earlier this month in which Hubbard’s nephew says he qualified for the 100 metres and the high hurdles too, but was not allowed to compete in those events because they were for whites only. Camille Paddeu, a curator at the Musee municipal d’Art et d’Histoire in Colombes, the Paris suburb where the main stadium was located, confirmed Hubbard was not permitted to compete in some events. You can read more about that here if you’d like.