Whether he does it before the end of this season (which he could) or not until the start of next year, Alex Ovechkin will very soon pass Wayne Gretzky as the leading goal-scorer in NHL history. Like so many of the records Gretzky set, this one seemed like it would never be broken. We’ll try to avoid any politics here, so let’s not think about Gretzky being a friend of Donald Trump and Ovechkin of Vladimir Putin. We don’t get to pick our moments, and the breaking of the all-time NHL record for goals is too momentous for someone who calls himself a hockey historian to ignore. So please read on for an all-time account of the NHL’s all-time leading goal-scorers…

The first NHL games were played on December 19, 1917. The Montreal Wanderers hosted the Toronto Arenas and beat them 10–9. The Montreal Canadiens were in Ottawa and beat the Senators 7–4. The Canadiens game in Ottawa was scheduled to start at 8:30 that night but was delayed for about 15 minutes. The Wanderers and Arenas faced off in Montreal at 8:15, officially making it the NHL’s first game. Dave Ritchie of the Wanderers scored just one minute into the first period against Toronto, giving him the honor of scoring the first goal in NHL history. But Ritchie wouldn’t remain the career scoring leader for long.

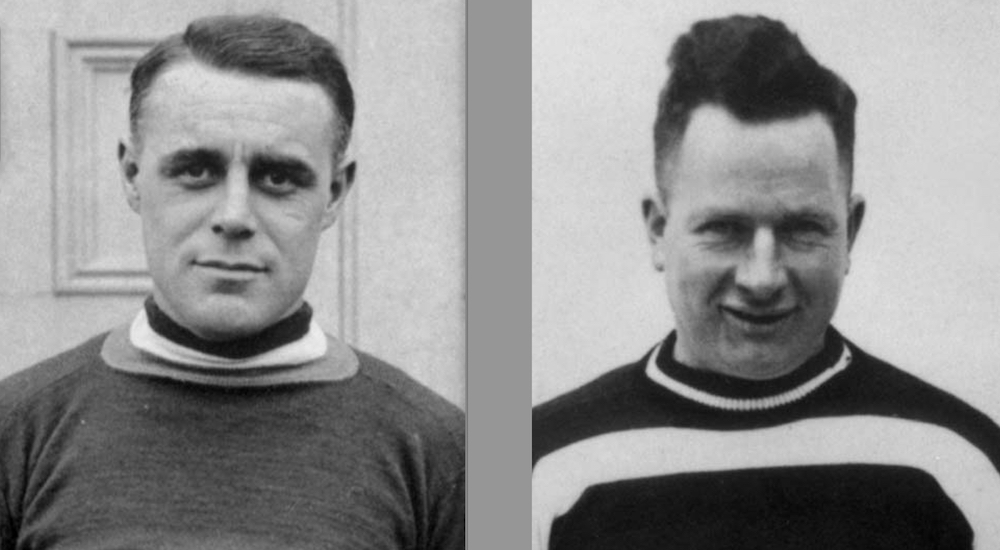

Two players scored five goals apiece on the first night in NHL history: Harry Hyland of the Wanderers and Joe Malone of the Canadiens. Hyland quickly fell off Malone’s pace, but Cy Denneny of Ottawa, who scored three in a losing cause on opening night, kept up. In fact, by the fourth game for each player, played on December 29, 1917, Denneny moved atop the leader board with 12 goals to Malone’s 11. Denneny reached 13 through five games on January 2, 1918. Malone scored twice in his fifth game on January 5 to reach 13 as well, but Denneny scored twice that night in his sixth game to hit 15. Malone moved back on top on January 12 when he scored five again to reach 20 on the season in just his seventh game played.

Joe Malone ended the NHL’s first season of 1917–18 with a league-leading 44 goals in 20 games played which (of course!) gave him the all-time league lead at the time. Malone played just eight games in 1918–19 and scored seven goals. Cy Denneny, who was second in the NHL with 36 goals in the first season, equalled Malone as the all-time leader when both scored their 45th career goals on January 4, 1919 and Denneny surpassed Malone with three goals on January 9 to give him 48. Denneny finished the 1918–19 season as the NHL’s career leader with 54 goals to Malone’s 51

Joe Malone moved to the top of the leaderboard again during the 1919–20 season. Playing with the Quebec Bulldogs, Malone matched Denneny with 55 career goals on January 1, 1920 and moved ahead again when he scored four in his next game on January 7. Malone would lead the NHL that season with 39 goals, which gave him 90 in his career.

100 CAREER GOALS

Joe Malone, Hamilton Tigers. February 5, 1921 vs Clint Benedict, Ottawa Senators.

(Milestone goal was Malone’s second of two in a 7–3 loss.)

On the night Joe Malone scored his 100th goal, Newsy Lalonde of the Montreal Canadiens reached 99 for his NHL career. Lalonde scored two in his next game on February 9, 1921, to reach 101. Malone scored once that night, so they were tied as the NHL’s all-time leaders. On February 12, Malone re-took the lead 103–102. Then, on February 16, Malone scored three to reach 106 … but Lalonde scored five to reach 107. By February 19, they were tied again at 108. On February 23, 1921, Joe Malone scored four to reach 112. Lalonde scored only once that night and Joe Malone would remain the NHL scoring leader for the rest of his career.

Joe Malone’s final goal — his only goal of the 1922–23 season (he scored no goal in 10 games in 1923–24) — came on February 3, 1923, in the Montreal Canadiens’ 4–1 win over the Ottawa Senators. He finished his NHL career with 143 goals in 126 games. Cy Denneny of the Ottawa Senators moved ahead of Malone atop the NHL career list again just two weeks later, scoring his 144th on February 17, 1923, versus the Hamilton Tigers’ Jake Forbes.

After passing Newsy Lalonde to take back the NHL career lead in goals, Joe Malone remained the leader for just under two years / 724 days (February 23, 1921 – February 17, 1923) until Denneny passed him again as the overall leader.

200 CAREER GOALS

Cy Denneny, Ottawa Senators. March 4, 1925 vs Clint Benedict, Montreal Maroons.

(Milestone goal was Denneny’s only goal of the game in a 5–1 victory.)

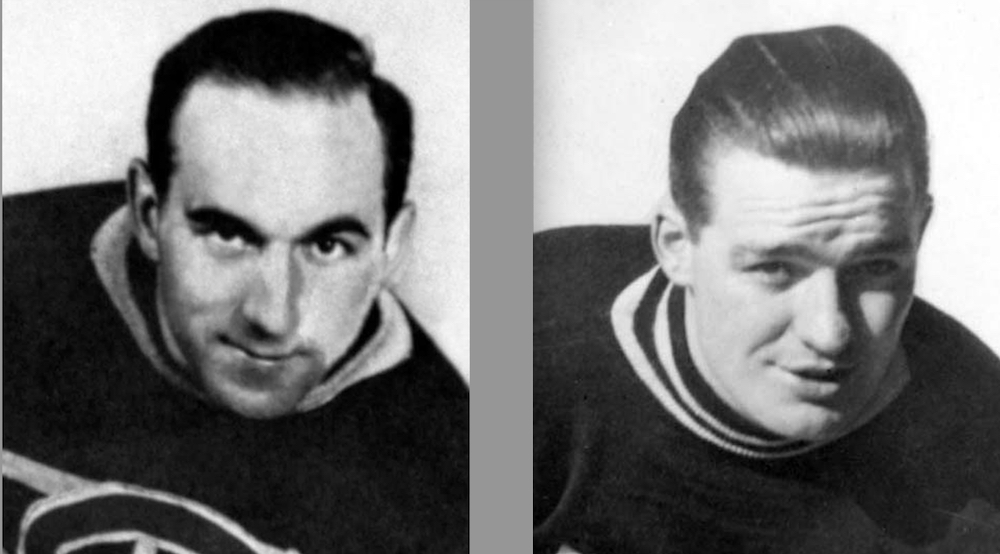

Cy Denneny scored his 247th and final goal on December 4, 1928, as a member of the Boston Bruins against the New York Rangers’ John Ross Roach. In all, he scored 247 goals in 329 NHL games. Howie Morenz surpassed Denneny for the NHL career lead with his 248th goal on December 23, 1933, also against Roach, who was then with the Detroit Red Wings.

After Cy Denneny surpassed Joe Malone as the NHL’s leading goal scorer, he remained the NHL’s leader for 10+ years / 3,962 days (February 17, 1923 – December 23, 1933) until being surpassed by Howie Morenz.

Howie Morenz scored his 271st and final goal on January 24, 1937, versus the Chicago Black Hawks’ Mike Karakas. Morenz suffered a career-ending broken leg two games later on January 28, 1937 (he’d played 550 games) and would die of complications while still in hospital on March 8, 1937. By the time of his death, Morenz had already been surpassed as the NHL’s career goal-scoring leader by Nels Stewart of the New York Americans. Stewart scored his 272nd goal on February 16, 1937, against the Montreal Canadiens’ Wilf Cude.

After Morenz became the NHL’s leading goal scorer, he remained the NHL leader for three+ years / 1,151 days (December 23, 1933 – February 16, 1937) until being passed by Nels Stewart.

300 CAREER GOALS

Nels Stewart, New York Americans. March 6, 1938 vs Dave Kerr, New York Rangers.

(Milestone goal was Stewart’s only goal of the game in a 3–1 victory.)

Nels Stewart scored his 324th and final goal with the New York Americans on March 16, 1940, versus the Toronto Maple Leafs’ Turk Broda. He ended his NHL career with 650 games played. Maurice Richard of the Montreal Canadiens surpassed Stewart with his 325th goal on November 8, 1952, versus the Chicago Black Hawks’ Al Rollins. Richard had scored his first career goal, in his second NHL game, exactly 10 years earlier. That goal had come unassisted against Steve Buzinski of the New York Rangers at 9:11 of the second period in a 10–4 Montreal victory.

After Nels Stewart became the NHL’s leading goal scorer, he remained the NHL leader for 15+ years / 5,744 days (February 16, 1937 – November 8, 1952) until his mark was beaten by Maurice Richard.

400 CAREER GOALS

Maurice Richard, Montreal Canadiens. December 18, 1954 vs Al Rollins, Chicago Black Hawks.

(Milestone goal was Richard’s only goal of the game in a 4–2 victory.)

500 CAREER GOALS

Maurice Richard, Montreal Canadiens. October 19, 1957 vs Glenn Hall, Chicago Black Hawks.

(Milestone goal was Richard’s only goal of the game in a 3–1 victory.)

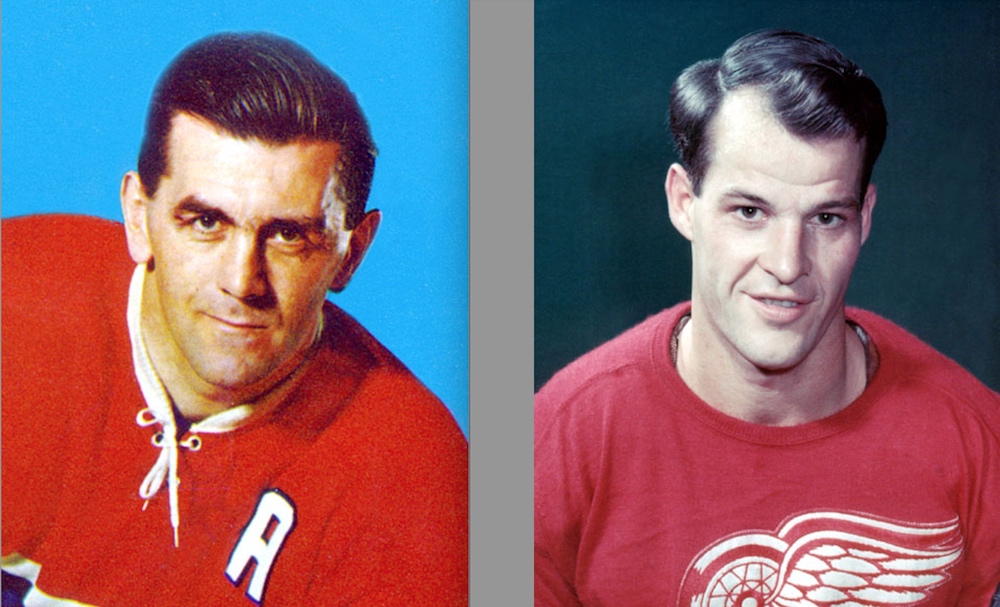

Maurice Richard scored his 544th and final goal on March 20, 1960, also against Al Rollins, who was then with the New York Rangers. He played 978 games in his career. Gordie Howe of the Detroit Red Wings moved past Richard with his 545th goal on November 10, 1963, versus the Montreal Canadiens’ Charlie Hodge.

After Maurice Richard became the NHL’s leading goal scorer, he remained the NHL leader for 11 years / 4,019 days (November 8, 1952 – November 10, 1963) until he was passed by Gordie Howe.

600 CAREER GOALS

Gordie Howe, Detroit Red Wings. November 27, 1965 vs Gump Worsley, Montreal Canadiens.

(Milestone goal was Howe’s only of the game in a 3–2 loss.)

700 CAREER GOALS

Gordie Howe, Detroit Red Wings. December 4, 1968 vs Les Binkley, Pittsburgh Penguins.

(Milestone goal was Howe’s only goal of the game in a 7–2 victory.)

Gordie Howe retired from the NHL after his 25th season in 1970–71 with 786 goals. At the time, Bobby Hull was a distant second on the career list with 554. Howe would return to action in the World Hockey Association in 1973–74. In his six seasons in the WHA, Howe had 174 goals and 334 assists for 508 points in 419 regular-season games. He returned to the NHL in 1979–80 at the age of 51, playing a full 80-game schedule with the Hartford Whalers.

800 CAREER GOALS

Gordie Howe, Hartford Whalers. February 29, 1980 vs Mike Luit, St. Louis Blues.

(Milestone goal was Howe’s only goal of the game in a 3–0 victory.)

In his final NHL season in 1979–80, Gordie Howe had 15 goals and 26 assists to bump his career goals total to 801. Howe scored his 801st and final goal in his last regular-season game (1,767 games) on April 6, 1980, against the Detroit Red Wings’ Rogie Vachon. He would remain the all-time leader until Wayne Gretzky scored his 802nd goal on March 23, 1994, for the Los Angeles Kings versus the Vancouver Canucks’ Kirk McLean. The Kings lost 6–3.

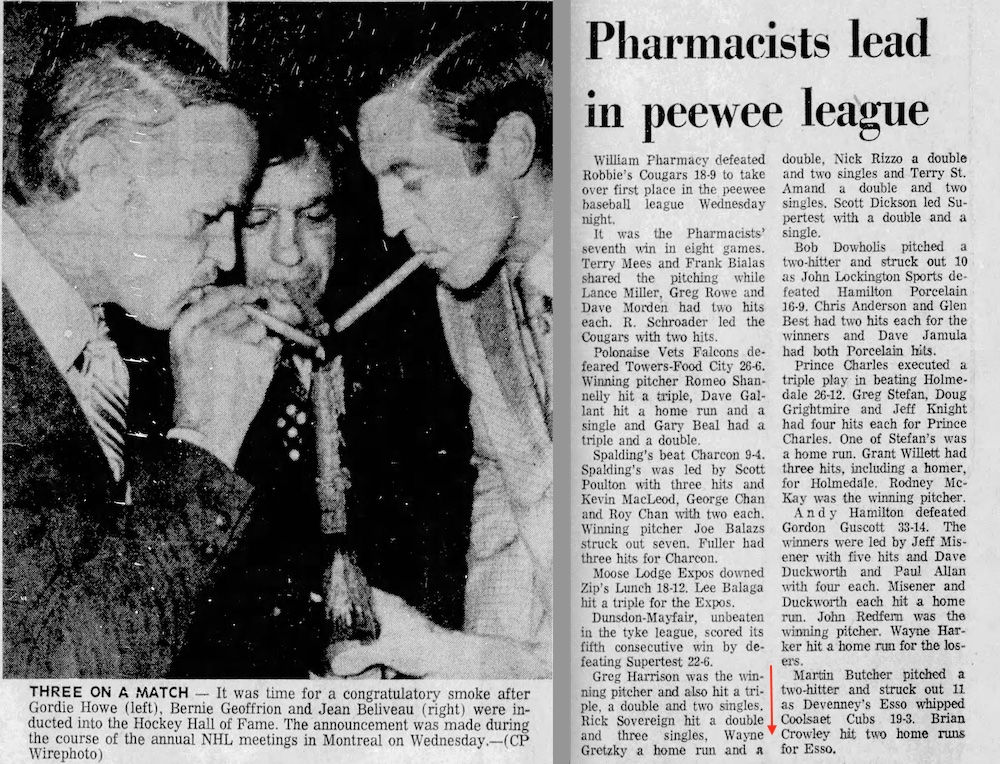

After Gordie Howe became the NHL’s leading goal scorer, he remained the NHL leader for 30+ years / 11,091 days (November 10, 1963 – March 23, 1994) until his mark was surpassed by Wayne Gretzky.

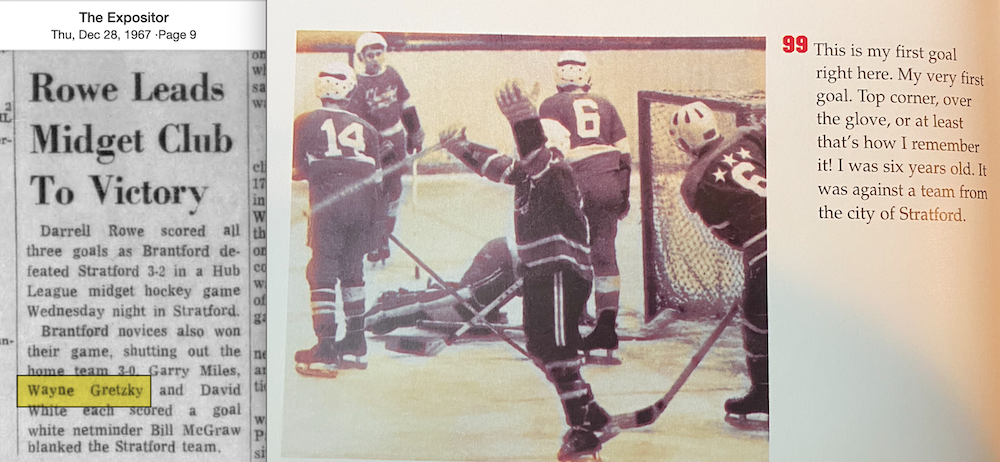

Wayne Gretzky scored his 894th and final goal on March 29, 1999, against the New York Islanders’ Wade Flaherty. He played 1,487 games in his career. As of this post on April 2, 2025, Gretzky still holds the record with Alex Ovechkin of the Washington Capitals closing in. Ovechkin has 891 goals in 1,484 career games with eight games to go in 2024–25. If he hadn’t missed 16 games earlier this season with a fracture fibula, Ovechkin might already have caught Gretzky. His final game of the regular season comes against Sidney Crosby and the Pittsburgh Penguins on April 17.

Since Wayne Gretzky became the NHL’s leading goal scorer, he has remained the NHL leader for 31 years / 11,333 days (March 23, 1994 – April 2, 2025).