I don’t mean to write off Chicago, and certainly not New York. Nor do I truly intend to demean the Ducks or the Lightning. But could anything say hockey LESS than Anaheim, California, facing Tampa, Florida, for the Stanley Cup … in June!?!

It would be a kick in the teeth for Canadian fans who await our country’s first NHL championship in 22 years and counting.

Hell will have truly frozen over.

Well, OK, maybe not. But when Montreal last won the Stanley Cup in 1993, it marked the eighth time in ten seasons that a Canadian team had won the title. Canadian teams were outnumbered by Americans at least two to one during the 50 seasons from 1944 through 1993, but Montreal, Toronto, Edmonton and Calgary still took home the Stanley Cup 35 times!

What’s happened since?!?

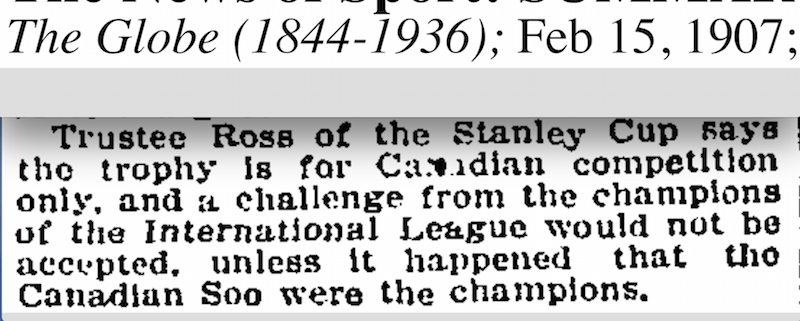

In the earliest days of hockey, Canadian teams won the Stanley Cup all the time. That’s because when Lord Stanley donated his trophy in 1893, he intended it to be awarded to the championship team in the Dominion of Canada. The first official Stanley Cup enquiry by an American team came in February of 1907 when the Pittsburgh Pros announced they would challenge for the Stanley Cup if they won the International Hockey League championship. On February 15, 1907, The Globe in Toronto reported that Stanley Cup trustee Philip Dansken Ross would refuse the challenge. “Trustee Ross of the Stanley Cup says the trophy is for Canadian competition only…”

Five years later, Ross’s fellow trustee William Foran refused to even accept the idea that two Canadian teams might play for the Stanley Cup on American ice, even if only to take advantage of the artificial ice in the Boston Arena. “Defending teams may play for the silverware in any rink or in any city they may choose, but not in the United States. The cup was donated for the championship of Canada, and we will certainly oppose any move to play for it outside the Dominion.”

But on December 8, 1915, the trustees changed their tune. “The Stanley Cup is not emblematic of the Canadian honors,” said Mr. Foran, “but of the hockey championship of the world. Hence, if Portland or Seattle were to win … they would be allowed to [claim] the trophy.”

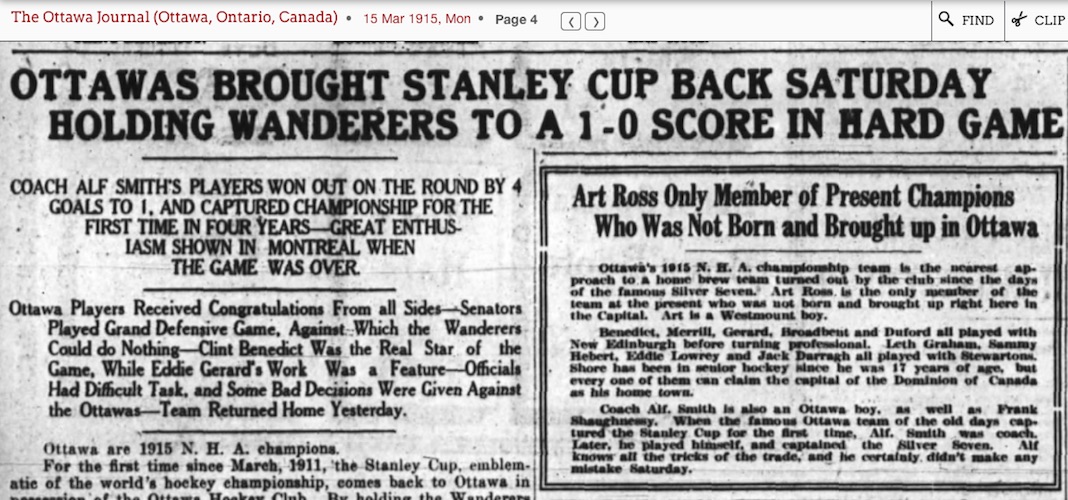

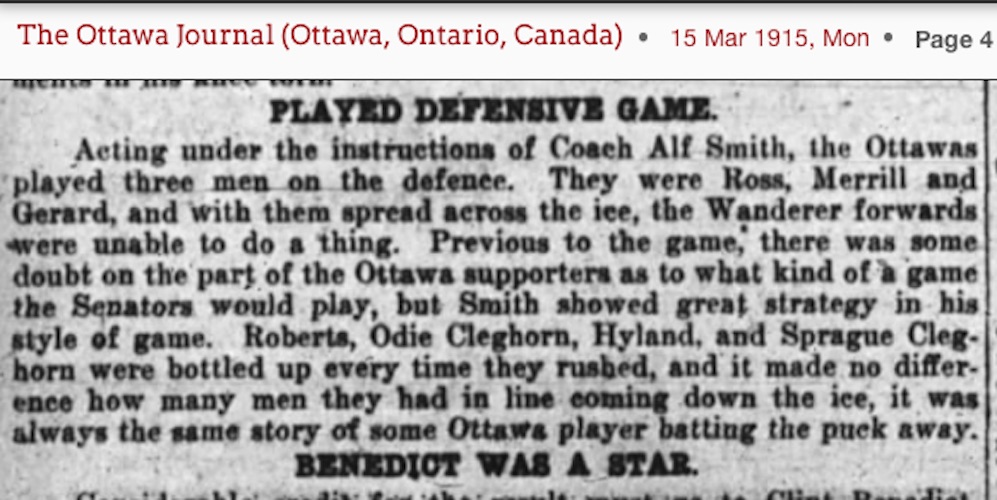

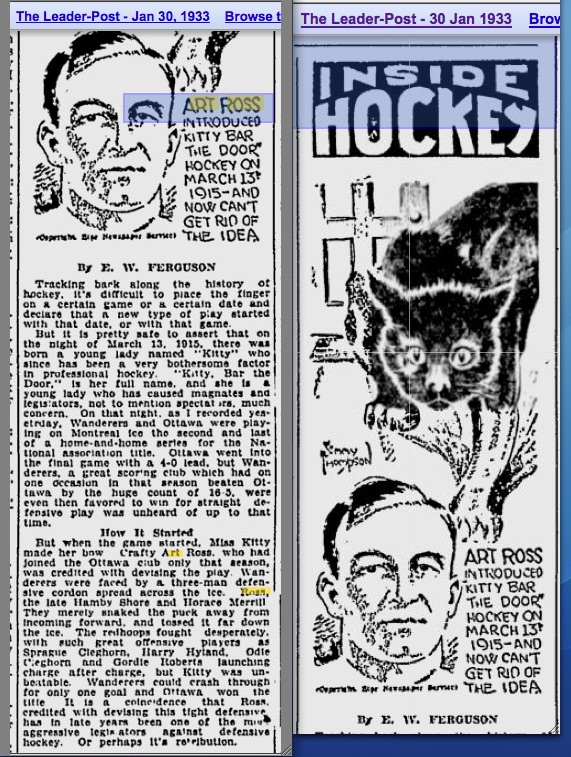

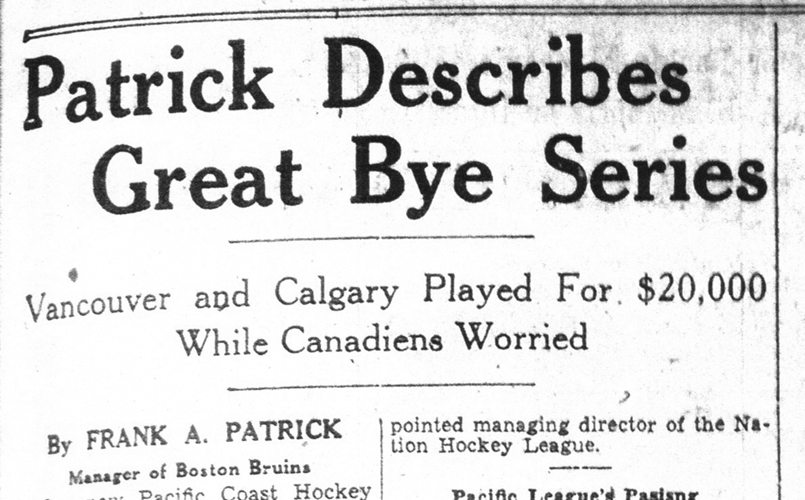

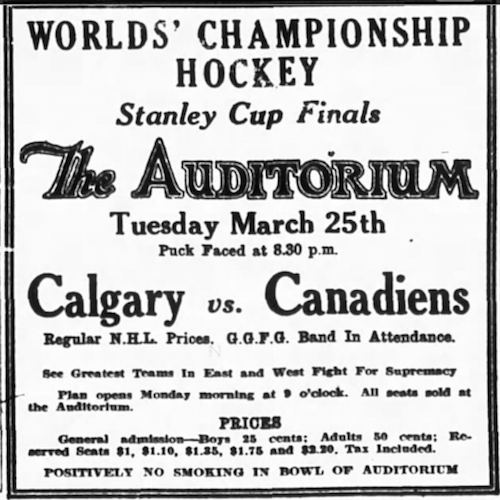

Why the sudden change? Well, at this time hockey had two major leagues: the National Hockey Association (forerunner of the NHL) and the Pacific Coast Hockey Association. Like the NHL and the WHA many years later, players would pit owners against each other, jumping from league to league and driving up salaries. But with the NHA continually breaking its agreements with the PCHA, there was a very real chance that the Stanley Cup would be scrapped. Declaring that the PCHA’s American franchises could compete for the Cup was a way to help keep the peace. In 1916, the Portland (Oregon) Rosebuds became the first American team to play in a Stanley Cup series. They were beaten by the Montreal Canadiens. A year later, the Seattle Metropolitans defeated Montreal, and the Stanley Cup went south of the border for the very first time.

The NHL replaced the NHA in 1917-18, but didn’t expand southward until the 1924-25 season when the addition of the Boston Bruins (as well as the Montreal Maroons) saw the league grow from four teams to six. By the 1926-27 season, the NHL had grown to ten clubs with six of them based in the United States. American teams have outnumbered Canadians ever since. In 1928, the New York Rangers became the NHL’s first American Stanley Cup champion and one year later, the Bruins defeated the Rangers in the first All-American Stanley Cup Final.

Sportswriters in American cities found the NHL’s protracted playoffs to be laughable, even in 1929 when Boston wrapped up the season on March 29. The Bruins had already beaten the Rangers to finish first in the American Division during the 1928-29 regular season, so why did they have to play them again for the Stanley Cup? This certainly didn’t happen in baseball, where only the first-place teams in the National and American leagues advanced to the World Series.

“[W]hy not evolve some plan for flooding and freezing the ball parks,” wondered a writer known only as “Sportsman” who penned the Live Tips and Topics column in the Boston Globe, “and [have] hockey all summer?”

Hmmm. Maybe the NHL has missed something by staging all those outdoor games in the dead of winter!