You don’t hear the terms Neutral Zone Trap or Left Wing Lock much these days, but the NHL is once again in a scoring slump. There’ve been exciting games in the current playoffs, and a few 6-2 scores, but basically, postseason play has resembled the low-scoring pre-lockout days of the late 1990s and early 2000s, complete with plenty of clutching and grabbing.

“When I came into the league,” said Sidney Crosby shortly after his Pittsburgh Penguins were eliminated in round one by the New York Rangers, “you knew [penalties] were going to be called because the league was promoting a certain style of play. Now I don’t know… Cleary the standards have changed.”

During the regular season, Jamie Benn of the Dallas Stars won the Art Ross Trophy with just 87 points in 82 games. It’s the lowest total in a non-lockout season since Stan Mikita scored 87 in 72 games in 1968–69, and the lowest points-per-game total since Elmer Lach led the NHL with 61 points in 60 games in 1947–48. That was the year that Art Ross and sons donated their trophy to the NHL to reward the league’s leading scorer.

The Art Ross Trophy is what Art Ross is best known for today. To many fans, it’s all he’s known for – although students of NHL history know he spent 30 years running the Boston Bruins from their inception in 1924 through 1954. Before that, during the pre-NHL years from 1905 to 1917, Ross was one of the best defensemen in hockey. His was a high-scoring era, and Ross was a star at both ends of the ice. He wasn’t Bobby Orr on offense. Probably closer to Raymond Bourque, only rougher. (It was once said of Ross that he never started a fight, but never came out second best in one either!) His stamina would make Chicago’s Duncan Keith look like a shirker – although Ross was one of the first to speak out in favor of more frequent substitutions in an era of 60-minute men.

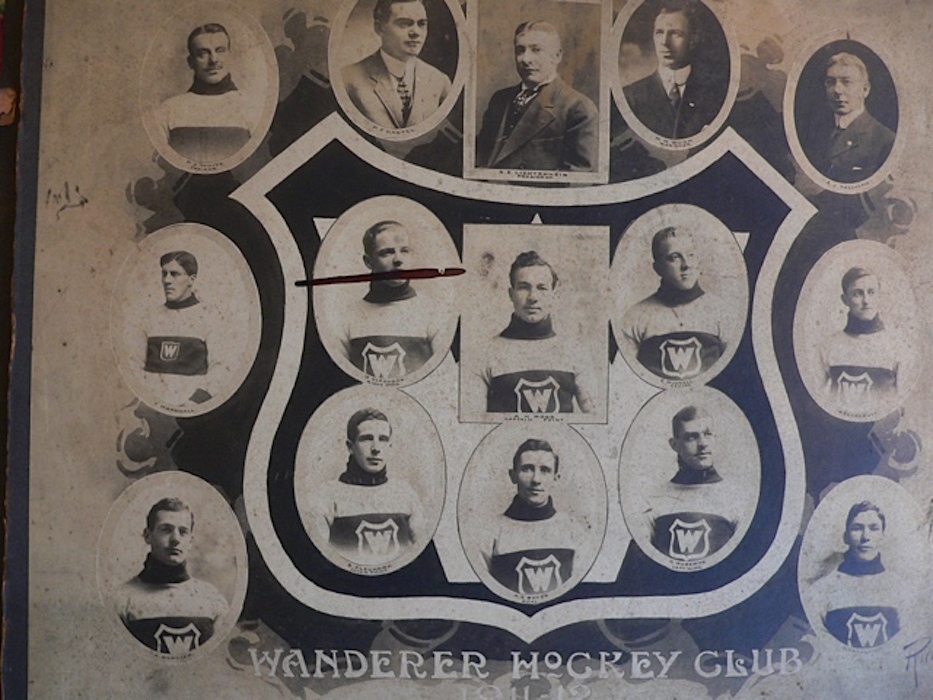

Captain Art Ross of the 1911-12 Montreal Wanderers is pictured in the center square.

Today, his name is synonymous with offense, but Art Ross is credited for coming up with hockey’s original defensive-trap system 100 years ago this spring … although Ross’s role in devising it may be less fact and more fiction.

Ross was playing with the Ottawa Senators in 1914–15 and was going up against his longtime former team, the Montreal Wanderers, in a tie-breaking playoff to decide the championship of the National Hockey Association, forerunner of the NHL. The Wanderers of Sprague and Odie Cleghorn, Gord Roberts, and Harry Hyland (largely forgotten now, but big names in their era) were hockey’s best offensive team. They scored 127 goals during the 20-game schedule of 1914–15 for an average of 6.35 goals-per-game! Ottawa scored just seventy-four times, but the Senators’ sixty-five goals against were by far the fewest in NHA.

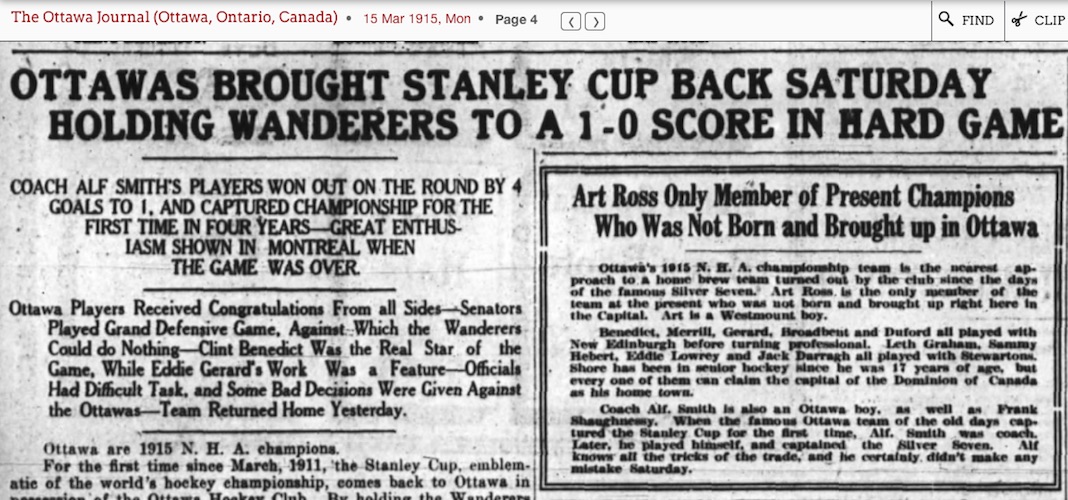

But this was a time when scorers ruled the ice, so the Wanderers were favoured over the Senators when their two-game, total-goals playoff opened on March 10, 1915. Even after Ottawa won the opener 4–0 at home (future Hall of Famer Clint Benedict’s shutout that night was the first in the NHA all season!) the Wanderers were expected to rally at home. After all, they’d beaten the Senators 15–6 and 8–1 in their two regular-season meetings in Montreal.

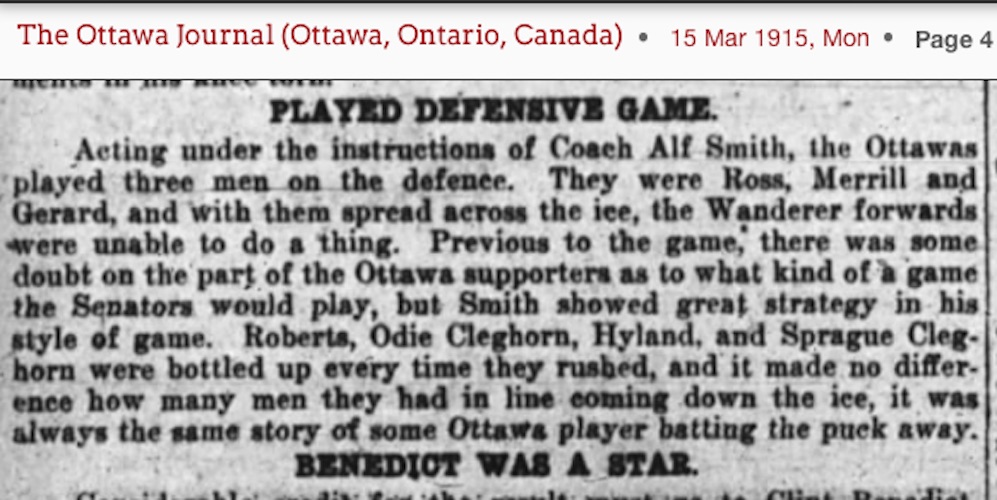

Newspapers speculated that Ottawa would come out hard in game two on Saturday night, March 13, looking for a few more goals to put the series away. But right from the opening face-off the Senators’ true intentions were clear. Ottawa employed only a center plus one winger on the forward line and spread out three defensemen across the ice.

“I was the only man to move,” Ross recalled around 1949. “I played right defense and if a Wanderer came down their right wing I’d move up and crash him while the other fellows shifted over to cover my position. If the puck-carrier came down on my side I’d go up to check him as I would have naturally.” With forward passing against the rules at this time, “we stopped them cold.” The result was a tediously dull game, and though the Wanderers got the only goal, Ottawa took the series with a combined victory of 4–1.

Ross remembered that he and his teammates came up with their three-man defensive system while on the train from Ottawa to Montreal, but on the day of the game, The Ottawa Journal reported that Ross was already in Montreal (where he lived) when the rest of the Senators departed from the Capital. In reporting on the game in their Monday edition, The Journal repeatedly stated that the Senators were “acting under the instructions of Coach Alf Smith” in employing their defensive system. Ottawa had obviously been a strong defensive team all season, and it certainly makes more sense for their long-time coach to have devised their tactics rather than their newly signed defenseman, even if he was one of the game’s biggest stars. Yet over the years, legendary sportswriters Baz O’Meara and Elmer Ferguson would repeatedly credit (or blame) Ross for the development.

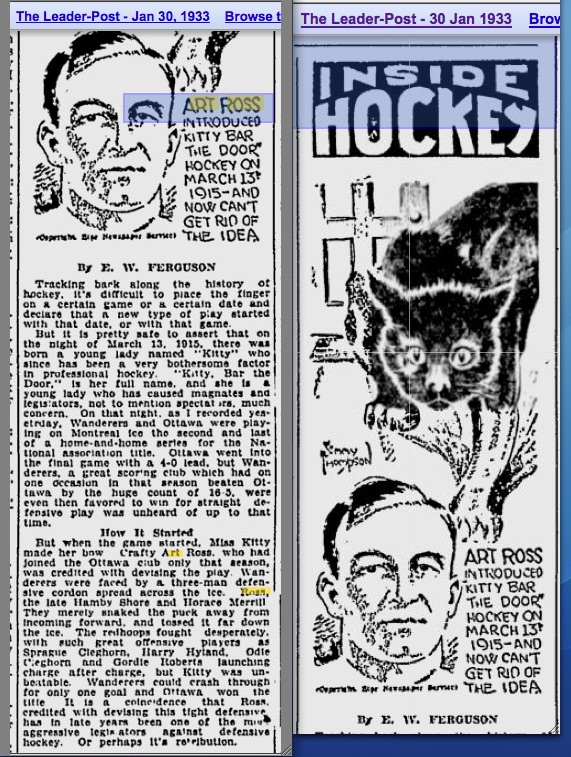

“Tracking back along the history of hockey,” Ferguson wrote in his syndicated column Inside Hockey in 1933, “it’s difficult to place the finger on a certain game or a certain date and declare that a new type of play started with that date, or with that game. But it is pretty safe to assert that on the night of March 13, 1915, there was born a young lady named “Kitty” who since has been a very bothersome factor in professional hockey. “Kitty, Bar the Door,” is her full name … [and] crafty Art Ross [devised] the play.”

By then, Ross had introduced many changes to the NHL rule book designed to improve offensive play, and his Bruins routinely boasted many of the league’s best scorers, yet the defensive reputation stuck to him. Perhaps that’s why he eventually donated the trophy that he did.

Excellent article. It just goes to show you (and by that I mean me) that there is always a further aspect to a story.

Thanks, Craig. Of course, there’s always the chance Art Ross came up with the plan just like Ferguson and O’Meara often wrote … but nobody told it that way at the time, and there are certainly plenty of facts that don’t line up!

Again it is very informative and an interesting read. Good work.

Glen