Around these parts, winter has been nothing like the long, tough slog it’s been the past two years. Then again, the forecast is for a big blizzard tomorrow! So, it’s always a good feeling to know that pitchers and catchers have reported to Spring Training. It means summer can’t be too far away. Last January, I posted a story called Hockey Stars Join Baseball’s Maple Leafs. Today’s post continues the story of Babe Dye and Lionel Conacher.

Seasons started later in 1926 (the Maple Leafs opened on April 14 that year), but spring training was already in the news by this week in February. Even so, Toronto’s baseball team wouldn’t actually get down to business until about March 10. At that point, there was still a week to go in the NHL season. When it wrapped up on March 17, Babe Dye’s Toronto St. Pats had missed the playoffs, but Lionel Conacher’s Pittsburgh Pirates qualified for a semifinal series against the eventual Stanley Cup champion Montreal Maroons.

“Manager [Dan] Howley is none too well pleased that post-season hockey may further delay the reporting of Babe Dye and Lionel Conacher,” reported the Toronto Star on March 22, 1926. “Howley feels that since St. Pats have finished the NHL season that Dye should lose little time joining the Leafs, and Conacher should also come on at once if Pittsburgh is eliminated by Montreal.”

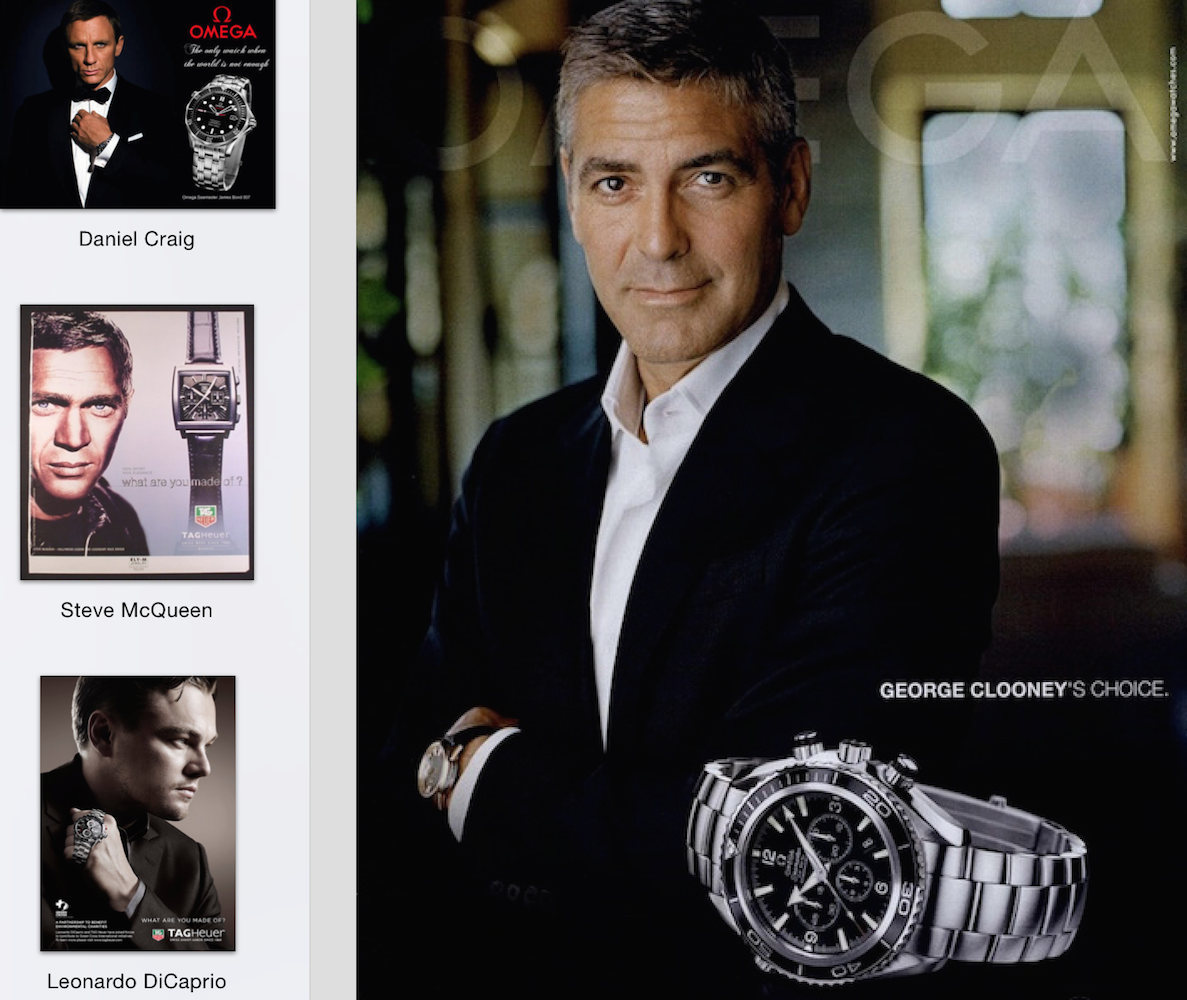

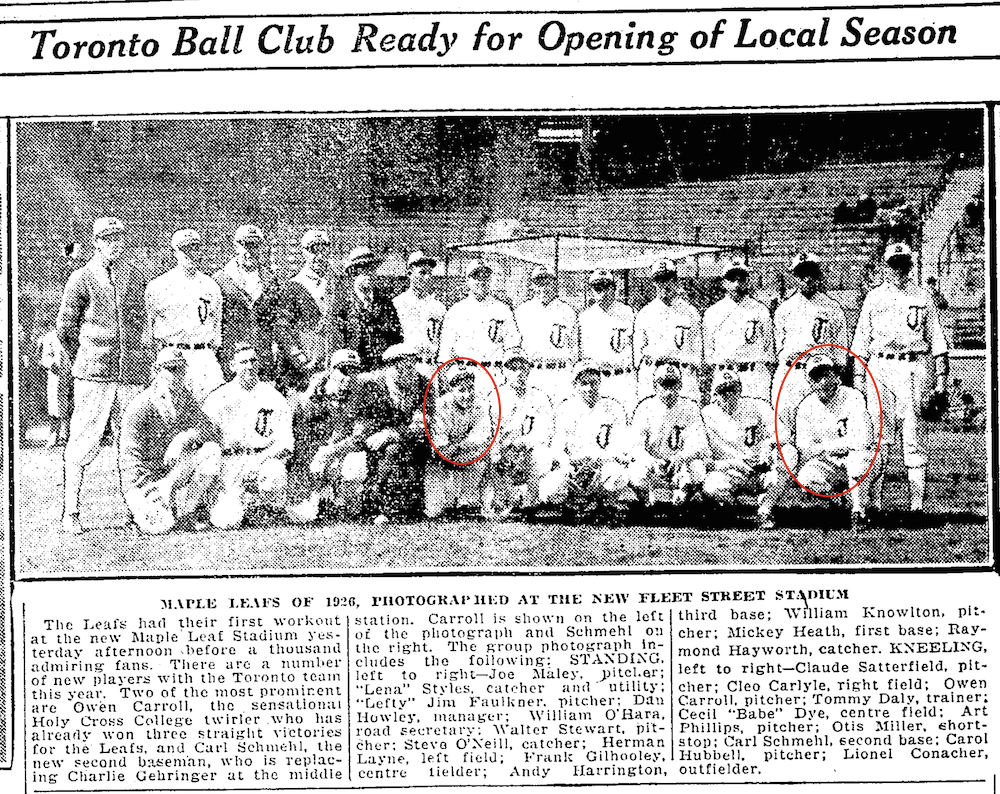

From the Toronto Star on April 28, 1926. Babe Dye is in the red oval near the centre; Lionel Conacher at the right. (Baseball Hall of Famer Carl Hubbell is to Conacher’s left.)

Conacher’s Pirates were eliminated the following day, and the Star noted: “The failure of Babe Dye to report is causing Manager Howley some anxiety. He is expected to join the club the latter part of this week. It is likely that Conacher will accompany his fellow-hockeyist.” The Globe reported that “Babe Dye today wired Manager Howley asking permission to delay his reporting until March 28, as he is not feeling very well. His wish has been granted.”

Dye finally showed up at the Maple Leafs’ Augusta, Georgia, training camp on March 29. Conacher didn’t report until April 6. Dye had only had one hit in 18 at-bats before that day, but suddenly went 5-for-6 with a pair of doubles. Conacher was in uniform the next day, taking batting and fielding practice with the team.

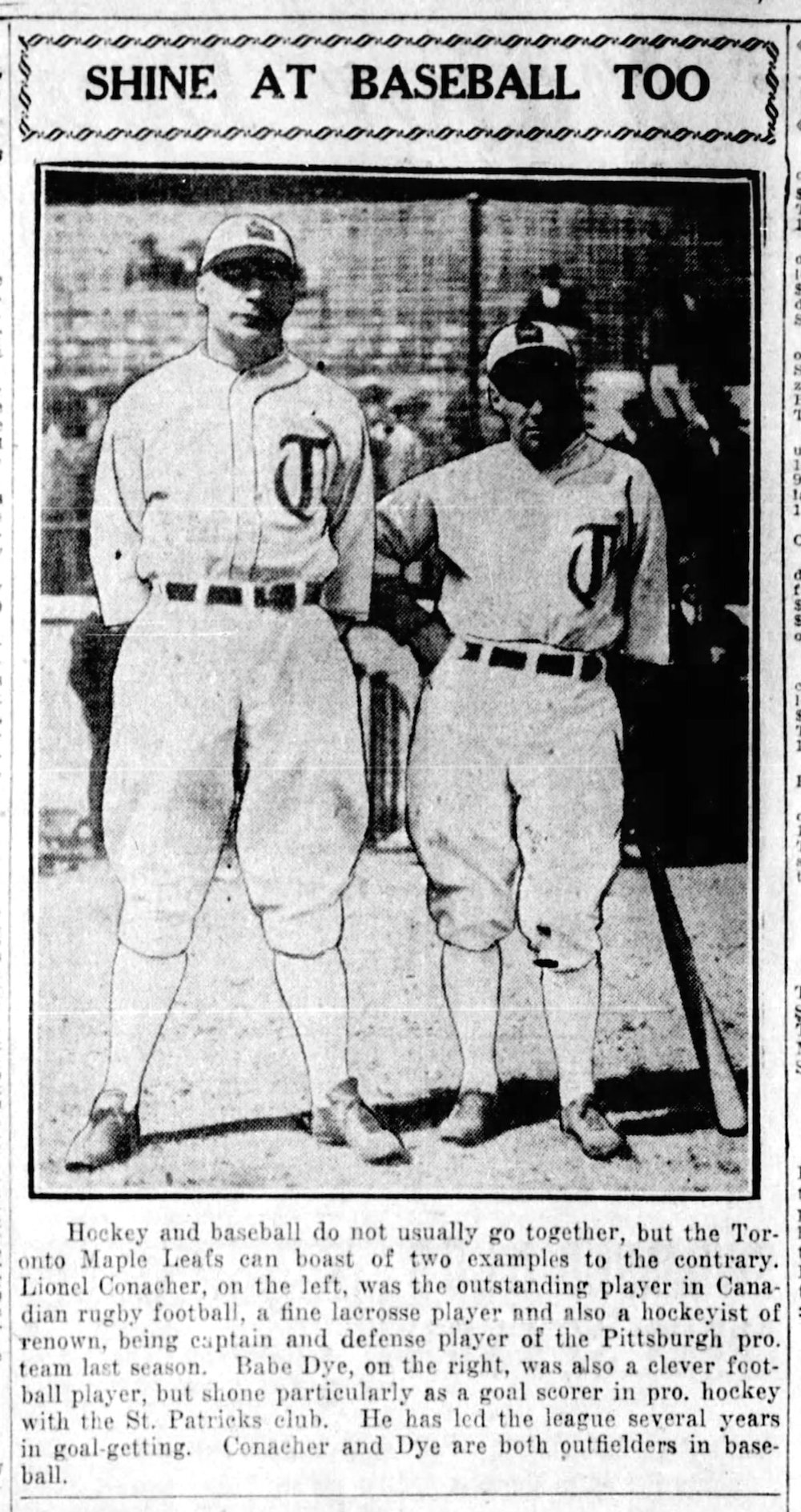

As noted in my story last year, Conacher was a great all-around athlete. He was best known as a lacrosse and football player but had made himself into a fine hockey player too. He’d been a good amateur ballplayer in Toronto, but hadn’t really played the game in three years! Still, “Manager Howley feels confident that the Toronto boy will develop into a good outfielder,” reported the Globe on April 7. Conacher was put into his first game the next day, and recorded his first hit, first run (the game-winner, in fact) and first putout as a professional baseball player in a 9-8 Toronto win over a team from Richmond, Virginia.

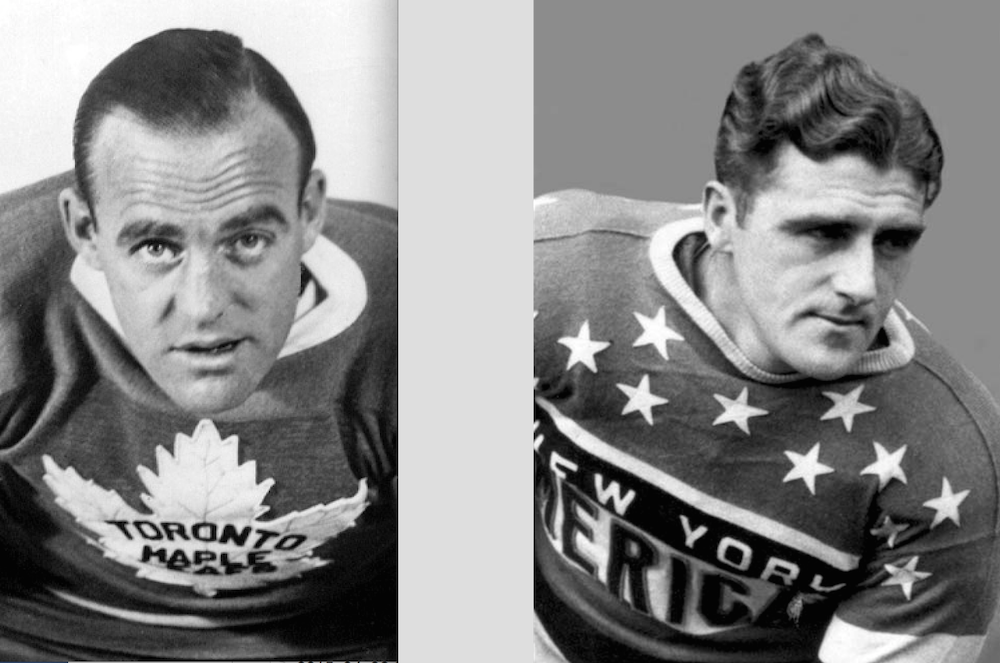

This photo appeared in the Winnipeg Tribune on June 14, 1926.

Both Dye and Conacher broke camp with the team, though neither played in the season-opening 8-2 win over Reading on April 14. Dye was a proven minor-league star, and was played up in the publicity to promote Toronto’s home opener at the brand new Maple Leaf Stadium on April 28 … but as also noted in my story last year, neither hockey star contributed much to what would be a championship season for the baseball Maple Leafs in 1926.

With the Blue Jays set to mark their 40th season this year, I for one think it would be cool to seem them wear the 1926 Maple Leafs uniform as a throwback nod to the 90th anniversary of the old ballpark at the foot of Bathurst Street. For some even better photographs of the uniforms, check out this web site.