If I was an historian who specialized in Canada’s military in World War I, I feel like no one would question that. But I’m a person who likes Canadian hockey history from that same era. While it does occasionally make me someone of interest — say, during a global pandemic when reporters want to talk about the Spanish Flu and the 1919 Stanley Cup — people often find it strange.

I can’t really explain why it’s the early history of hockey — mostly before the formation of the NHL — that interests me the most. If you look at old pictures of hockey players from these pioneer days, it’s hard to believe that any of them could skate fast enough, or shoot hard enough, to actually play the game let alone to entertain anyone today. And, of course, if you put them in a time machine and brought them to the present, there’s no way they could keep up. But my personal theory is, if you put them in a time machine and brought them to a point in time where they’d be born to come of age currently, the best of them would still grow up to be stars today.

Of course, there’s no way to prove that, but the one thing that you can prove just by reading old newspapers is that the hockey played in every era was always the fastest and the best it could be … and that the fans loved it! No one in 1911 was saying, “this game will be great some day if they ever shorten the shifts, and these guys grow bigger, stronger, and faster.” Most people today don’t know many of the stories, or the personalities, from those early days … but I find them fascinating. Everything that truly formed the modern game was beginning to happen in its early days.

Back in 1911, Marty Walsh was one of the biggest names in hockey with the Ottawa Senators. He’s in the Hockey Hall of Fame, but not having played since 1912, he’s only remembered today by those who really know the early days well.

A native of Kingston, Ontario, Walsh had starred for the hockey team at Queen’s University from 1903 to 1906. He was also a top football player for Queen’s, and would coach the Ottawa Rough Riders in 1911.

Walsh joined the Ottawa Senators in 1907–08, a year after the Eastern Canada Amateur Hockey Association first allowed professional players to suit up with amateurs. Cyclone Taylor also arrived in the Canadian capital that year, and would serve as the Bobby Orr to Walsh’s Phil Esposito. They each appear to have added something new and lasting to hockey that season, with Taylor shouting for passes when he wanted the puck, and Walsh tapping his stick on the ice when he wanted it.

Cyclone Taylor became a defenseman in Ottawa, and, like Bobby Orr, he could do it all. Marty Walsh was a center who scored goals like few others in his day. In what was essentially Walsh’s first season as a pro in 1907–08, he scored 27 goals in just nine games and placed second in the ECAHA behind Russell Bowie, who scored 31 times in 10 games. (Bowie is another name few know today, but he was the greatest scorer in hockey in the early 1900s when players routinely played all 60 minutes.) The next season, in 1908–09, Walsh led the league with 42 goals in 12 games as he and Taylor helped bring the Stanley Cup to Ottawa.

Two years later, in 1910–11, Walsh led the National Hockey Association (forerunner of the NHL) in scoring. Sources vary, but he either scored 35 goals or 37 in a 16-game season. What is undisputed is that in a single-game Stanley Cup challenge on March 13, 1911, Walsh scored three goals to provide the margin of victory in a 7–4 win over the Galt Professionals. Three days later in another one-game Stanley Cup challenge on March 16, Walsh scored 10 times in a 13–4 win over Port Arthur. That’s a performance topped only at the highest level of hockey by Frank McGee’s legendary 14 goals for Ottawa against Dawson City in 1905.

Marty Walsh was more than just a hockey star. He was a guy that everybody seemed to like. Walsh was a man who could be quick with a quip, but was also as good as his word … even if others might not be.

After the Senators’ Stanley Cup win in 1909, the owners of what would become known as the Renfrew Millionaires hoped to attract several top stars to their tiny town in the Ottawa Valley. (This is a big part of the plot in my very first book, the novel Hockey Night in the Dominion of Canada.) Renfrew had already signed Cyclone Taylor and looked certain to lure several other stars away from the Senators as well.

George Martel of Renfrew was reportedly offering Walsh $500 up front plus a contract paying him $2,500 for the 1909–10 season. Walsh had nothing but a gentleman’s agreement with his Ottawa team, and likely for only about half as much money, but he refused to jump.

“I will give you three thousand cash for this season,” Martel shouted, unable to understand the Ottawa star’s hesitation.

“And I repeat,” said Walsh, “that you haven’t got money enough to make me sign until Mr. Bate releases me of my promise to him. A Walsh never broke his word.”

It’s said that Walsh’s refusal to take Renfrew’s money saved the Senators by convincing several other Ottawa players to stay with the team. But unfortunately for Walsh — and for all other hockey players of their day – after the free spending ways of the 1909–10 season, hockey owners hoped to recoup their losses by instituting the game’s first salary cap for the 1910–11 season. Teams in the NHA planned to sign no more than 10 players and to pay them just $5,000. Not $5,000 a piece… $5,000 for the entire team!

Senators players seemed particularly vocal in their displeasure. During preseason salary negotiations, when Walsh returned to Ottawa from his home in Kingston, it was reported that while he was looking forward to the coming winter, he felt that “$500 wouldn’t pay his beef steak bill at Benny Bowers’ (a cafe popular among Ottawa sportsmen) during the hockey season.”

The salary dispute in 1910 briefly led to the game’s first player strike. It’s unclear how effectively NHA owners actually held the line on salaries that year, but the Senators were said to have signed only eight players and paid them all $625 apiece. (The decision to change the structure of the game from two 30-minute halves to three 20-minute periods may have made it slightly easier for Ottawa to get by with just seven regulars.) It’s also been said that, as a championship bonus, management allowed the Ottawa players to split all the gate receipts from their two Stanley Cup games and from a postseason tour of New York and Boston.

Despite any lingering resentment over the reduced salaries in 1910–11, the Senators had had no real competition that year. They started the 16-game schedule with 10 straight wins and finished the five-team regular season with a 13–3 record, well ahead of Renfrew and the Montreal Canadiens, who both finished 8–8. (The Montreal Wanderers were 7–9, while the Quebec Bulldogs went 4–12.)

A year later, in 1911–12, the NHA eliminated the position of rover — a seventh player who had lined up between the forwards and the defensemen — to create the six-man alignment that remains the standard in hockey to this day. It’s never been completely clear if this was done for competitive reasons or as just another way to save money, but Ottawa players weren’t happy with this move either. “You might as well do away with the shortstop in baseball,” Walsh complained.

With essentially the same lineup as in 1910–11 but now playing six-man hockey in 1911–12, the Senators fell to 9–9 in the expanded 18-game season and dropped into second place in a tight four team race that saw Quebec top the NHA with a 10–8 record to claim the league title and the Stanley Cup. The loss of the rover had definitely hurt the Senators.

“When the rules were changed,” explained goalie and team captain Percy Lesueur, “we were completely at sea and it took half the season to get any system in our play…. In the seven-man game we used to play [a] three-man combination … [W]hen a combination was broken up, there was no one there to check the man; the rover had been done away with and there was no trailer to the three-man rush…

“In previous seasons we had depended a lot upon the center man being able to hang around the nets and get the rebounds, at which Marty Walsh shone.” Indeed, a description of Walsh’s style in the Ottawa Citizen a few years later, on February 11, 1916, noted that he often liked to flip a soft shot at the net and then — in an era where goalies didn’t have specialized gloves, carried their sticks with two hands like other players, and were not allowed to drop to the ice and smother shots – “take an extra swing if the first [shot] did not ring the bell.” But, as Lesueur explained back in 1912, “with the six-man game the center man had no chance to do that; he had to be back on the job [defending]. That threw us off a lot.”

Walsh basically lost his job as Ottawa’s main man at center during the 1911–12 season. He took part in only 12 of 18 scheduled games and dropped from 30+ goals to 11. He never played again. After just five seasons, and at only 27 years of age, Marty Walsh walked away.

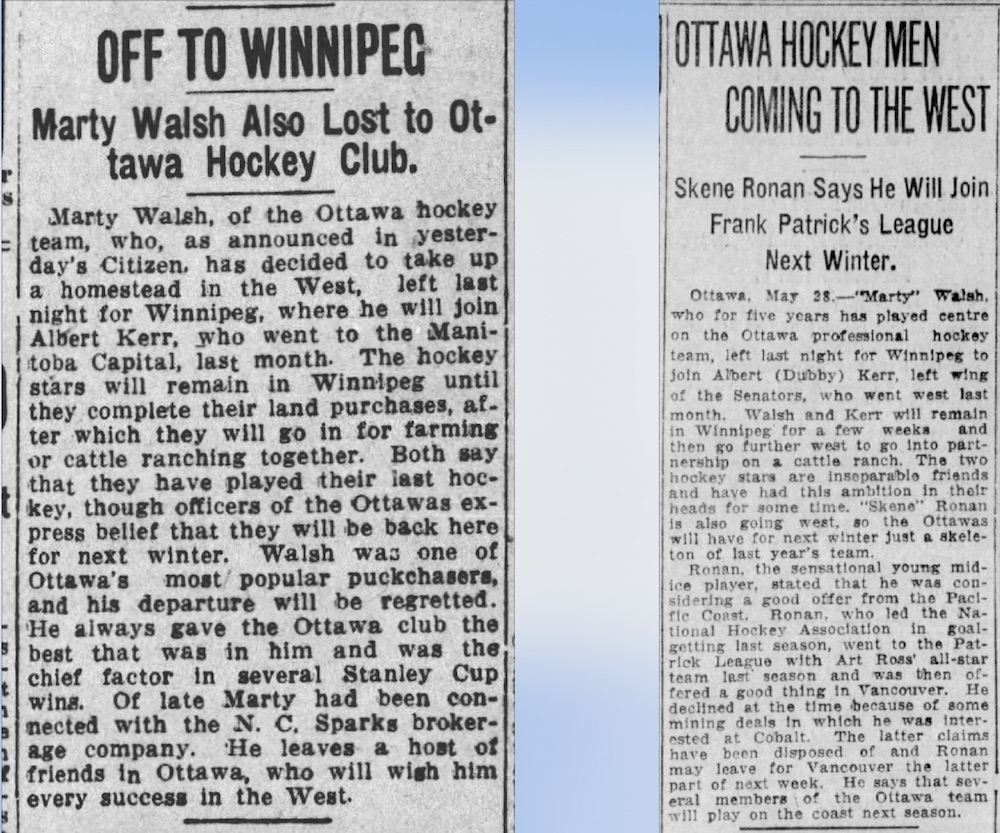

Reports in April of 1912 indicated that Walsh was moving to Winnipeg with an Ottawa teammate, Dubbie Kerr. A story in May quoted an unnamed Senators star (probably not Walsh) as saying that players were still angry that management in Ottawa had failed to deliver on promises made when the players turned down the lucrative Renfrew offers. Walsh, it was said, was interested in playing for the rival Pacific Coast Hockey Association.

Walsh left for Winnipeg to join Dubbie Kerr at the end of May in 1912. Some newspapers claimed they were going to buy a Western cattle ranch. Others said they were looking for a farm. These stories may never have been true, as Walsh moved on to Edmonton in July and took a job with the Grand Trunk Pacific railway. (Kerr stayed in Winnipeg, but reportedly took a job with the Canadian Northern railway.) Rumors that Walsh would join a PCHA team — Vancouver was sometimes mentioned, but usually Victoria — continued into December.

There would soon be others stories saying that Ottawa wanted Walsh back, but he never signed with anyone. On December 28, 1912, the Edmonton Journal reported that he’d attended a local hockey game on Christmas Day (the Edmonton Eskimos defeated the Calgary Tigers 13–3) and Walsh soon joined the Eskimos as a coach. He remained in that role through the 1913–14 season.

During the fall of 1914, Marty Walsh left Edmonton. Around September, he relocated to a ranch outside of Cochrane, Alberta. Was it the cattle ranch he’d reportedly bought with Dubbie Kerr back in 1912? Maybe … but Walsh had actually moved on the advice of his doctors. Some time early in 1915, he moved again, this time to Gravenhurst in the Muskoka region of Ontario. Gravenhurst was the first site in Canada, and only the third in North America, with a sanitorium to treat patients suffering from tuberculosis.

By the end of February in 1915, Walsh was reported as being gravely ill with the deadly disease. Friends in his hometown of Kingston established a fund, which would be supported as well by the hockey community in Ottawa. (Frank Patrick of the PCHA is known to have made a donation, and one would have to think that the Edmonton hockey community also contributed.)

Marty Walsh died of tuberculosis on March 27, 1915. His funeral was held four days later, on March 31, at St. Mary’s Cemetery in Kingston. He was survived only by a sister, Mrs. Loretta Keaney of Sudbury. Frank McGee, then in training with the Canadian army in Kingston, represented the Ottawa hockey club at the funeral. The fund for Walsh had raised sufficient money to cover all of his medical and funeral expenses with enough left over to erect a commemorative monument at his grave which stands there to this day. Largely through the work of his nephew Martin Keaney (who was only about four years old when his uncle died), Marty Walsh was elected to the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1962 and inducted in 1963.

I have read all your newspaper articles, magazine articles, books both fiction and non fiction and heard you on radio and watched you on TV. But I have never heard of Marty Walsh. Thank you for a most interesting article and helping me pass some time as I sit here in self isolation.

Great story telling, Eric…..thanks for this. Hope you are keeping healthy and motivated during these strange times. How about a story with an Okanagan angle?

Thanks, Rod. I’m pretty used to working from home, so I’m holding on.

The Okanagan isn’t exactly a hockey hotbed is it? (More like, just a hotbed!) I know there are good stories about the Penticton Vees. This isn’t quite the right region, but it is one of my best B.C. Interior hockey tales…

http://ericzweig.com/2016/02/04/ghost-of-a-chance/

I started researching the 1920-30’s Pros before I started seeing the old names. No doubt it’s the most interesting era of hockey and I spent lots of time in the 00’s and 10’s from coast to coast in the US and Canada.

Before I read this, I had never heard of Marty Walsh. Thanks so much for some interesting history!

Having read all your books and most of everyone else’s that was written of this era, I too hadn’t heard of Marty Walsh. Great story Eric! Thanks for this.

He’s in there in some of what I’ve written… but never very prominently.