It is truly amazing the things that can be discovered online these days. Some times, maybe, it’s too much. I admit, this story almost feels like an invasion of privacy. Or even exploitive. But, it’s been going around in my head for days so I’ve written it all down.

I remember, years ago, when Barbara sent away for the complete military records of her grandfathers, who both served in World War I. Both survived, and Barbara knew them well when she was young. She adored her mother’s father, but the family had a more difficult relationship with her father’s father. She knew that her mother’s father had been wounded badly enough some time in 1918 that he spent the rest of the War in a hospital in England. He had difficulties because of his injuries until he died in 1964. After seeing his War records, we began to refer to him as “World War I’s most wounded soldier.” It seemed he just kept getting wounded, getting patched up, and getting sent back out there … until it almost killed him. The most notable thing about her father’s father was how often he was treated for venereal disease! I remember both Barbara and her mother saying how appalled he would be that they knew this about him.

But, at least those stories were all in the family. This one certainly isn’t. But here goes…

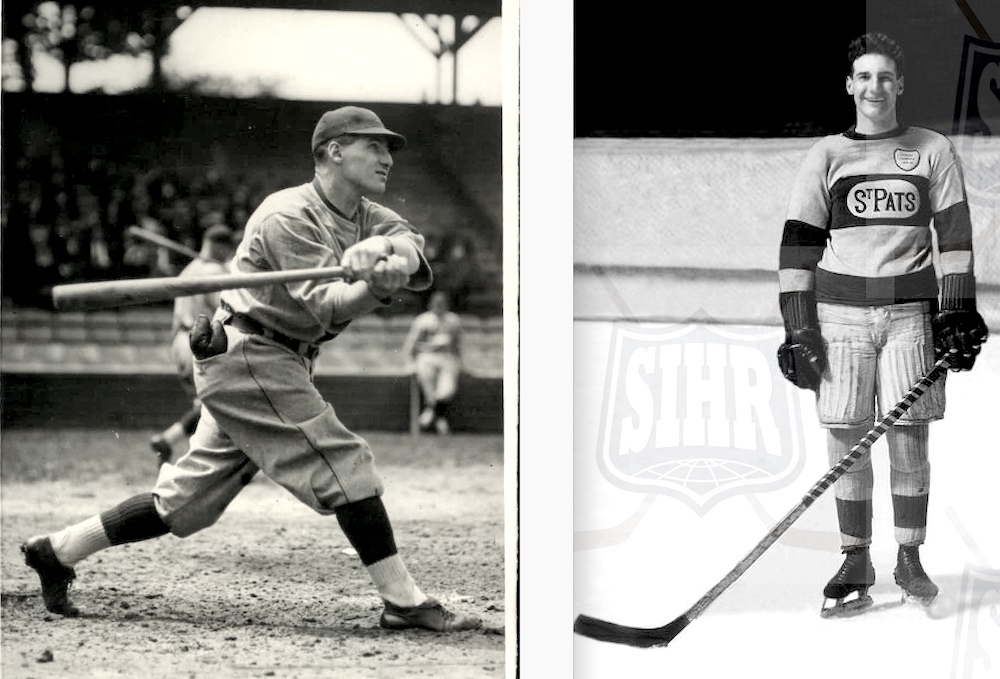

Recently, I wrote about Babe Dye being perhaps the first Babe Ruth of Hockey. I already knew a lot about his story, and have written about him here before, back in 2015 and 2016. Dye was a multi-sport star who became a top scorer in the NHL with the Toronto St. Pats in the 1920s while also playing high-level minor league baseball, mostly with the Buffalo Bisons and the Toronto Maple Leafs. Like Babe Ruth, Babe Dye was a left hander who pitched and played the outfield. Dye was also a fine football player, but was never a halfback with the Toronto Argonauts, as old hockey biographies used to say. He actually starred with a Toronto team called the Capitals from 1917 to 1920.

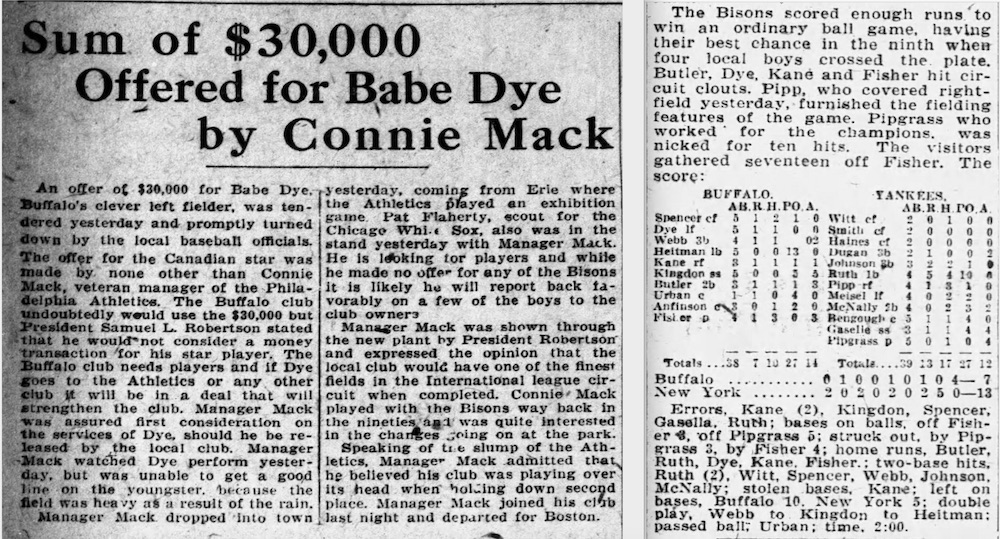

As a baseball player, Dye was good enough that the legendary Connie Mack wanted him for his Philadelphia Athletics. Hockey records long claimed that Mack offered $25,000 to Dye in 1921, which is what was reported in the Toronto Star along with an obituary for Dye on January 4, 1962, a day after he died. In truth, the offer came in 1923, and it appears to have been for $30,000. Hockey stories say Dye turned down Mack in order to concentrate on his NHL career, but the Buffalo Enquirer of August 29, 1923, makes it pretty clear that it was the Bisons who were actually offered the money to buy Dye’s rights. It was also the Buffalo team that turned down Mack because the Bisons wanted players in return, not money, if they were going to give up a perennial .300 hitter.

The Buffalo Bisons gave Dye permission to report late to spring training as

the St. Pats faced the Vancouver Millionaires in the Cup Final late in March.

And by the way, what an amazing coincidence that the day after Connie Mack was in Buffalo, the New York Yankees were in town to play an exhibition game against the Bisons … and that Babe Dye and Babe Ruth both hit home runs in the same game! (The Yankees beat the Bisons 13–7.)

So, by now you’re wondering, “what’s so personal about all this?” Well, bear with me a little longer…

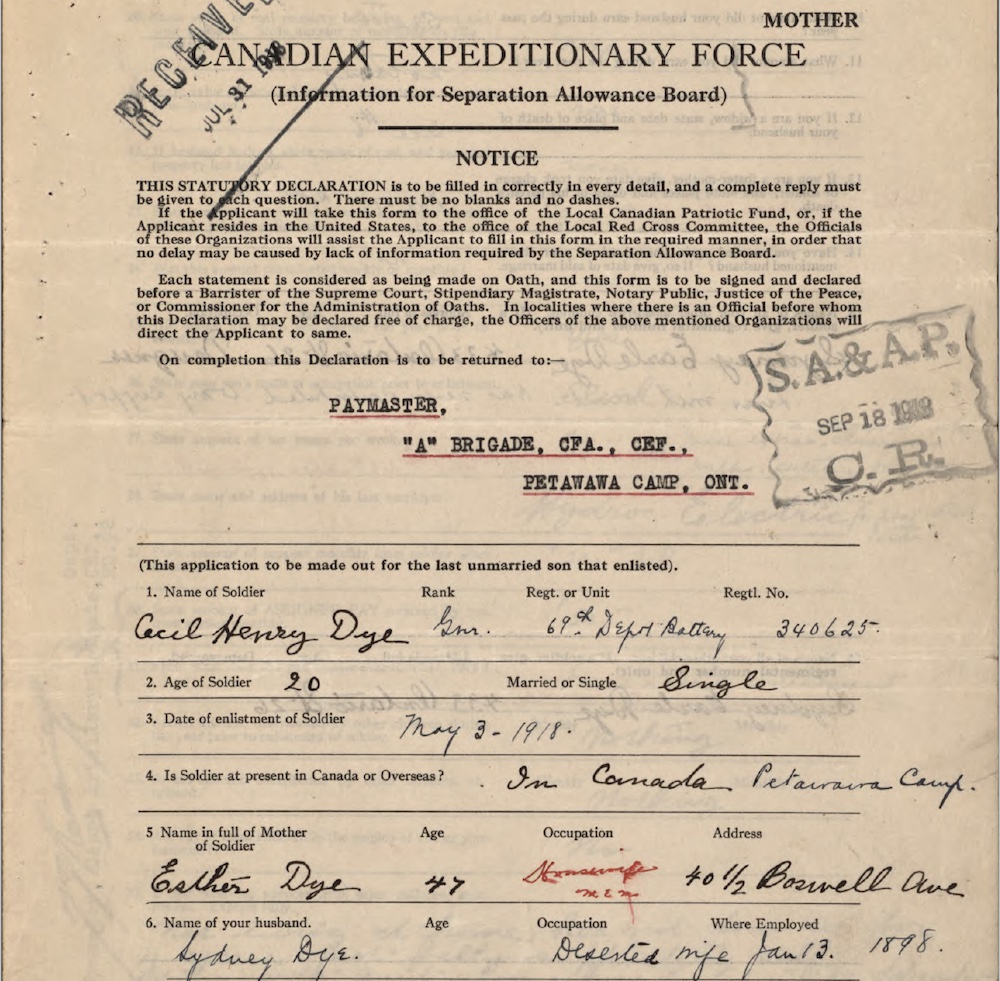

While poking around old newspaper stories about Babe Dye last week, I discovered that in May of 1918, he enlisted with the Canadian Expeditionary Force for service in World War I. Dye joined the 69th Battery of Toronto and was sent to Camp Petawawa (near Ottawa) to train as a gunner. (I had no idea of this, but others did. Alan Livingstone MacLeod writes about it in his book From Rinks to Regiments, and tells me that Dye’s name was on a list of hockey playing soldiers produced by the Department of Veterans Affairs.)

With the War ending on November 11, 1918, Dye was never sent overseas before being discharged on December 20. He seems to have spent an awful lot of his army time playing sports; often back home in Toronto. Dye played for the 69th Battery baseball team, and also pitched for his old Toronto baseball team, the Hillcrests, while home on leave a couple of times during the summer. He also played a few football games in Toronto with the Capitals on leave in the fall.

The 69th Battery won the military baseball championship at Camp Petawawa and actually played against the Hillcrests in the Ontario semifinals. The game was originally scheduled for Saturday, October 5, 1918, but wet grounds forced a postponement and the game was played the following weekend, on October 12. Though he had pitched for the Hillcrests during the season, Dye was given permission to pitch against them. Through five innings, he kept things close … until he hurt is ankle sliding into third in the top of the sixth. Dye attempted to continue pitching, but he couldn’t, and the Hillcrests (who were leading 2-1) scored six late runs for an 8-3 victory.

Later in life, Babe Dye would credit his athletic prowess to his mother, who apparently taught him to skate and play hockey and to pitch and play baseball. “My mother knew more about hockey than I ever did,” Dye once recalled, “and she could throw a baseball right out of the park.”

Dye, it was said, never knew his father, who died when he was only one year old. The family was living in Hamilton then, but his mother Esther brought young Cecil (Babe’s given name) and a brother back to Toronto, where she and her late husband were both from.

OK. Here’s where we get to the personal/privacy stuff!

There’s not much military information in Babe Dye’s military records, but there’s some fascinating family information.

In July of 1918, Esther Dye filled out an application for financial assistance, claiming that her son who was now in the military, was her main source of support. But she was not a widow. Her application states that her husband, Sydney Dye, (John Sydney Alexander Dye, I would later discover) had deserted her on January 13, 1898. She had received no support from him since then, and his whereabouts were unknown.

But what about the other son? Babe’s brother of the hockey stories, who Esther had apparently brought to Toronto after her husband died? Couldn’t he support his mother?

Apparently not.

Sydney Earle Dye “lives with an aunt,” Esther wrote. “Has never contributed to my support.”

It wasn’t so much that he never had, but that he never could.

“From the physical viewpoint, he is neither an invalid nor is he incapacitated,” wrote Dr. George B. Smith on Esther’s form in August of 1918. “From the mental viewpoint, he is totally neurotic and if not carefully handled his brainstorms would be unbearable…. He is unsuited to meet the public at large. He shuns publicity and society.” How long had he been like this? “From childhood.”

Not in the military records, but available if one searches hard enough on Ancestry, is the rest of the story…

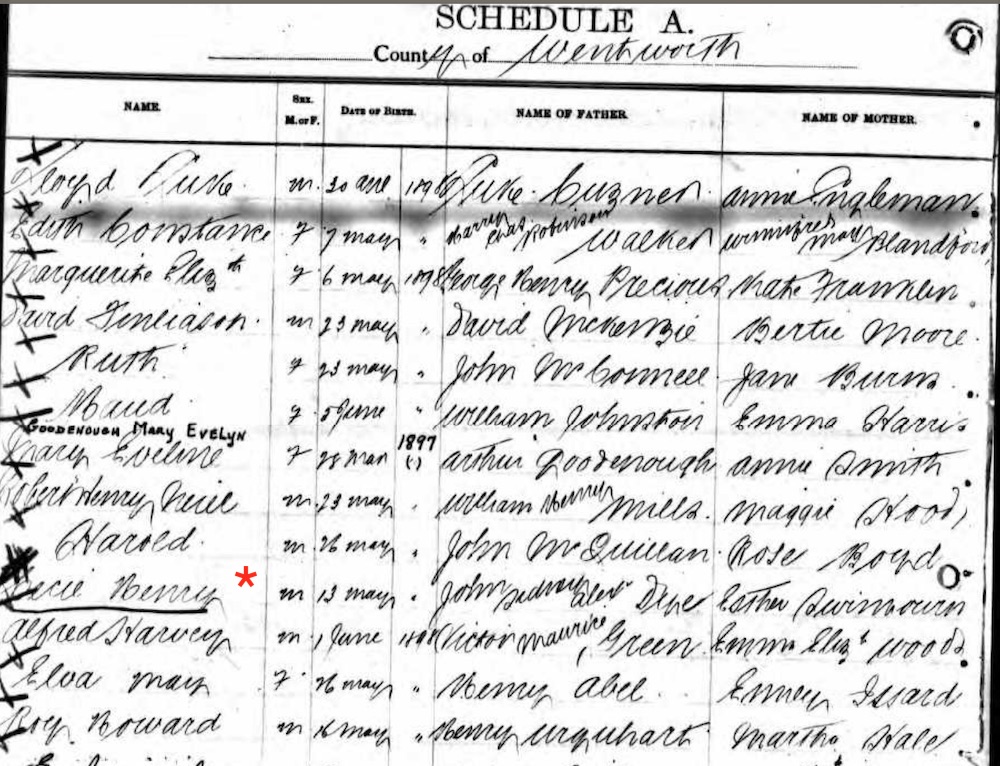

John Sydney Alexander Dye married the former Esther Swinbourne on May 22, 1891 (above, left). Sydney Earle Dye was born on September 6, 1891 (above, right). Do the math. That’s barely four months after the wedding. Esther must have been five months pregnant at the time. And, by coincidence (or maybe not?) Esther also seems to have been about five months pregnant when her husband left her in January of 1898, as baby Cecil would be born on May 13, 1898 (below).

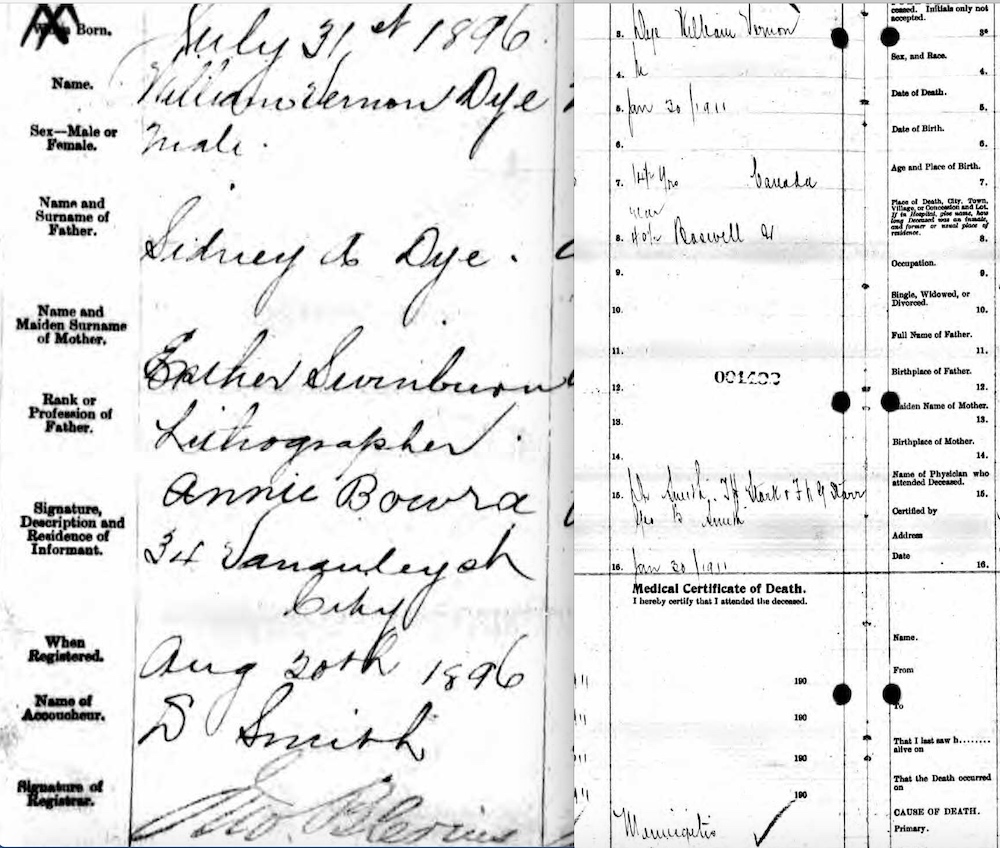

Esther raised Cecil on her own. She had two sisters who never married, but older brother Sydney (who went by Earl) was actually brought up by one of his father’s brothers and his wife. So the Dye family didn’t abandon Esther completely. And it further turns out that Babe Dye was one of three sons, not two. He had a second older brother, William Vernon Dye, who was born on August 20, 1896, but died of meningitis on January 20, 1911. Life was more difficult in those days, but it still must have been a difficult childhood. Sports must have been a comforting refuge.

These were definitely family stories you wouldn’t have read in an old-time biography of Babe Dye. I imagine it was stuff the family rarely spoke of. If ever.

But all the facts are out there now.

If you dig deep enough.

So, now we know.