You may have heard the news, which broke Monday of last week, about Mitch Marner being carjacked at gunpoint. Coming as it did, just two days after Tampa Bay eliminated Toronto in game seven of the opening round of the NHL playoffs, it sort of sounded like the start of a bad joke. But it wasn’t.

Sadly, both carjacking and violent crime is on the rise in Toronto, as it is in so many cities. There is no indication that the carjackers were targeting Marner, or that the theft had anything to do with the Maple Leafs. The thieves only wanted his Range Rover. Marner surrendered his keys without incident – which is what police recommend. He was shaken, but not physically hurt.

Eighty years earlier, in 1942, crimes committed against a previous member of the Toronto hockey club were decidedly less violent, but certainly more personal.

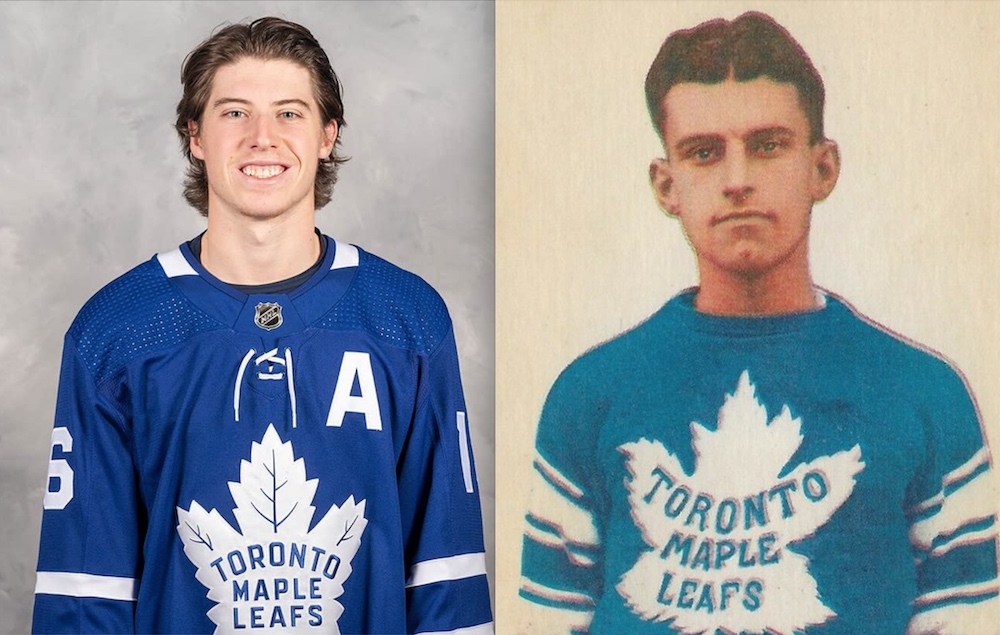

In a way, the Maple Leafs of the 1930s were similar to the current team. Led by stars such as Charlie Conacher, who won two scoring titles and led the league in goals five times, and Joe Primeau, who was a Lady Byng Trophy winner and three-time league leader in assists, the Leafs were an exciting, high scoring team that couldn’t seem to get it done when it came to the playoffs.

Of course, a 10-year drought from 1932 until 1942 was nothing like the 55-years-and-counting of the current club. Plus, the Leafs of the 1930s did manage to win a round or two over the years. Still, after winning it all in 1932, the Leafs lost in the Stanley Cup Final in 1933, 1935, 1936, 1938, 1939 and 1940. Then, as now, critics felt the team was too soft, or simply not motivated enough, to win when it mattered most.

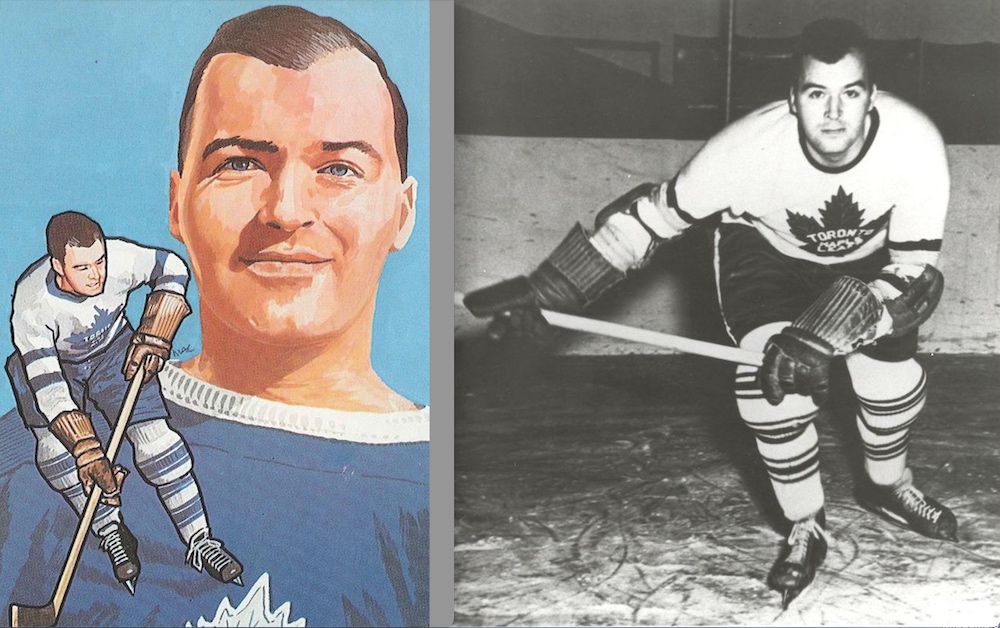

By the 1936-37 season, the Leafs had acquired two more young scoring stars in Syl Apps and Gordie Drillon. They also brought in Turk Broda as their new goalie that season. Still, Stanley Cup success was another five years off. Meanwhile, Drillon led the NHL with 26 goals and 52 points in the 48-game season of 1937-38, which makes him the last Leaf ever to lead the league in scoring. He continued to rank among the NHL’s top scorers over the next few years.

Drillon was a great points producer, but was a little less talented when it came to other skills. He wasn’t much at digging the puck out of corners, nor was he great in his own end. He was a sniper, not a skater, and when the Detroit Red Wings took a three-games-to-nothing lead over Toronto in the 1942 Stanley Cup Final, Drillon was one of the players the Maple Leafs benched in order to shake up the lineup. The changes resulted in four straight wins for Toronto … but it was a tough time for Drillon.

“I had been dreaming about that Stanley Cup ever since I was a kid,” Drillon told Vern DeGeer, Sports Editor of The Globe and Mail, for his column on April 28, 1942. “It grew and grew in my mind each season. But when the series was finished out, and I wasn’t even on the bench, that Cup grew smaller and smaller. Just a shattered dream, I guess. [I] simply couldn’t stand it, so Mrs. Drillon and I went home after the second period. Heard the last period on the radio.

“I tried to take the whole affair with my chin up. I didn’t play well in the first games against Detroit, but I had thought I would get back into uniform before the series was over, even as an extra forward.

“One of the toughest touches came after the fifth game here in Toronto. A bunch of hoodlums appeared at our apartment house about midnight, tossed stones at the windows, and put on a wild, hooting demonstration. Even the kids in the neighborhood got to booing me as I walked down the street. And only a few weeks previously I had been a pal to many of them.”

Unbeknownst to anyone, Drillon’s wife had been sick for some time and would soon require an operation. He never used it as an excuse, but he did tell DeGreer he was “going back to Moncton [and] I won’t be back with the Leafs next winter.”

It isn’t clear whether Drillon meant that he would refuse to return to Toronto or if he had been told that his services were no longer required by the Maple Leafs. Either way, Toronto sold him to Montreal for the 1942-43 season. Drillon score a career-high 28 goals for the Canadiens in 49 games played during the newly expanded 50-game schedule, but the next year, he left the NHL for service in the Canadian military during World War II.

After the war, Drillon returned to play a few seasons of senior hockey in the Maritimes. He never played in the NHL again, but (according to his biography for the Hockey Hall of Fame) he was welcomed back into the Maple Leaf family as their Maritime scout in the late 1960s, and recommended Errol Thompson to the Leafs brass.

Drillon certainly didn’t seem to hold any grudges. In March of 1985, he told Paul Patton of The Globe and Mail that he didn’t mind talking about the 1942 Stanley Cup. “Every time a team falls behind 3-0 in a playoff, even if it’s baseball, they bring it up,” he said. “That’s how people remember me.”

Fellow Maritimer and play-by-play legend Danny Gallivan reminisced about Drillon with Toronto Star columnist John Robertson for a story in that paper the day after Drillon’s death at age 72 on September 23, 1986.

“Gordie was a wonderful friend of hockey,” Gallivan recounted. “[He] never lost his love for the game, or became cynical or bitter as some old-timers did in their later years. When I put forward his name for the Hall of Fame [in 1975], a few of the skeptics said: ‘This man only played seven seasons in the NHL…’

Chicago goalie Alfie Moore in Game One of the 1938 Stanley Cup Final.

“‘Yes,’ I said. ‘But he went to war for his country at the age of 29, in the prime of his career…. He could have played another six seasons at least if he hadn’t volunteered. What a shame it would be to keep him out of the Hall of Fame because of that.’”

Gallivan added that Turk Broda had once told him that he didn’t think there was ever a player in hockey who could shoot with the accuracy of Gordie Drillon. “Even if you leave him an opening [just] the size of the puck,” Broda had said, “he’d hit it every time.”

Paul Patton had written that Drillon liked to park himself in front of the net, “dig in and deflect pucks past rival netminders. Fans complained that it was a lazy way of scoring, but Drillon practiced tipping shots until he became a master at the art.”

Leaving the last word for the man himself, Gordie Drillon told Patton, “I spent 10 years playing in the slot before anyone invented a name for it.”