Walter Smaill is not a name likely to be recognized by many hockey fans today. (Even my spell-checker keeps trying to change his name to Walter Small.) But that’s never stopped me before! Smaill is yet another OLD old-time hockey player I have great affection for.

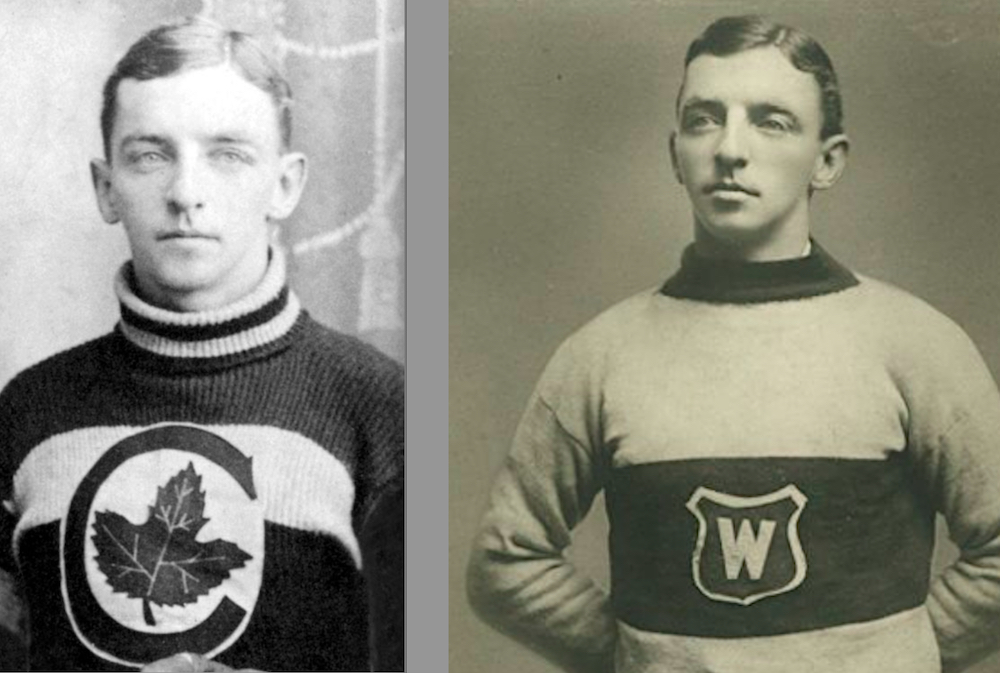

Walter Sydney Smaill was born in Montreal on December 18, 1884. He grew up in Westmount, playing local sports with other future hockey stars such as Art Ross, Frank and Lester Patrick, and Sprague and Odie Cleghorn. (He would play most of his his pro hockey career alongside Ross or Lester Patrick.) As Frank Patrick would write of those neighbourhood kids in the Boston Sunday Globe on January 27, 1935, in one of an eight-part series on his life when he was the coach of the Bruins, “Almost every young boy competed in football, baseball, basketball and [track] as well as hockey.” Walter Smaill was no exception. He grew up to play hockey, football, and lacrosse at the highest levels. He was also an excellent paddler, sailor, and swimmer.

When Smaill died at the age of 86 on May 2, 1971, he’d outlived almost all his contemporaries, save for Cyclone Taylor. Smaill lived most of his life in Montreal, but spent time in Victoria, Winnipeg, and a few smaller cities across the country too. In his younger days, he worked as an athletic instructor, often running sports clubs for youths, and even after going to work as a car salesman around 1925 he stayed involved in sports for many years, serving as a coach, referee, or league executive in hockey, lacrosse, football, canoeing, and other sports. He even served as an NHL referee during the 1924–25 season, and was suggested as a potential president of a professional hockey players union before the 1925–26 season. “Smaill denied all connection with the movement,” reported the Montreal Gazette on September 2, 1925. “He stated that ten years ago there had been such a move in which he had been interested, but that the present plans … did not concern him directly.”

Smaill seems to have been a guy that people liked, and likely because of his “good guy” status — and also because he lived so long — many sportswriters (particularly in Montreal) who’d been on the job since his playing days would occasionally mention his name in columns during the 1960s as someone who should be in the Hockey Hall of Fame. He was definitely a good player.

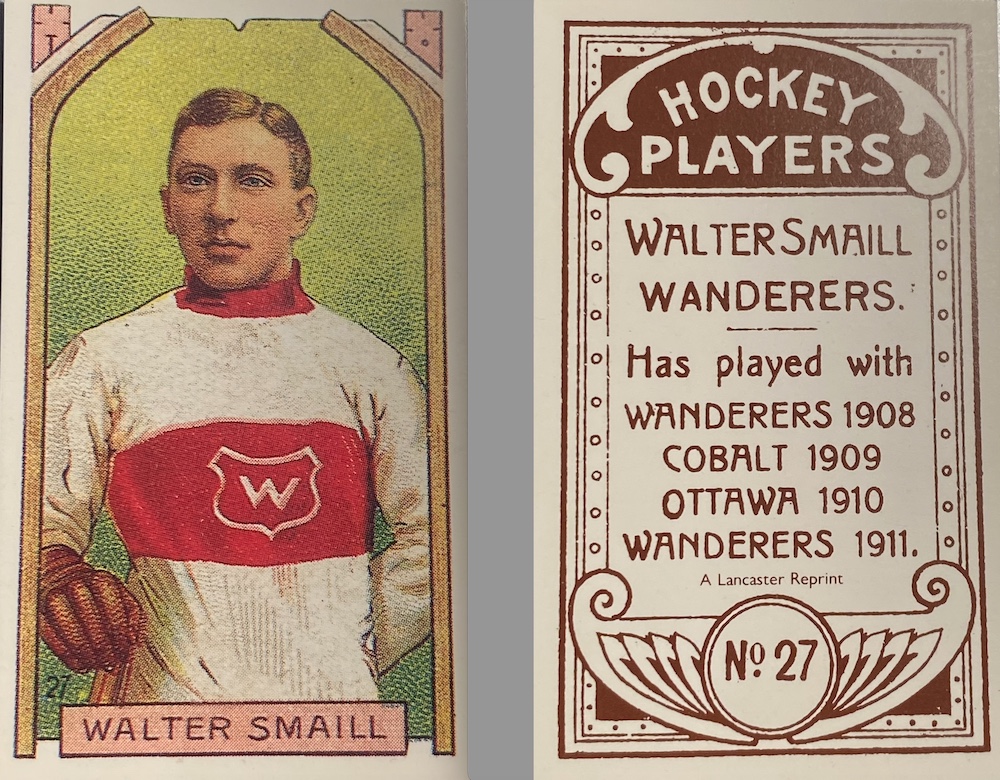

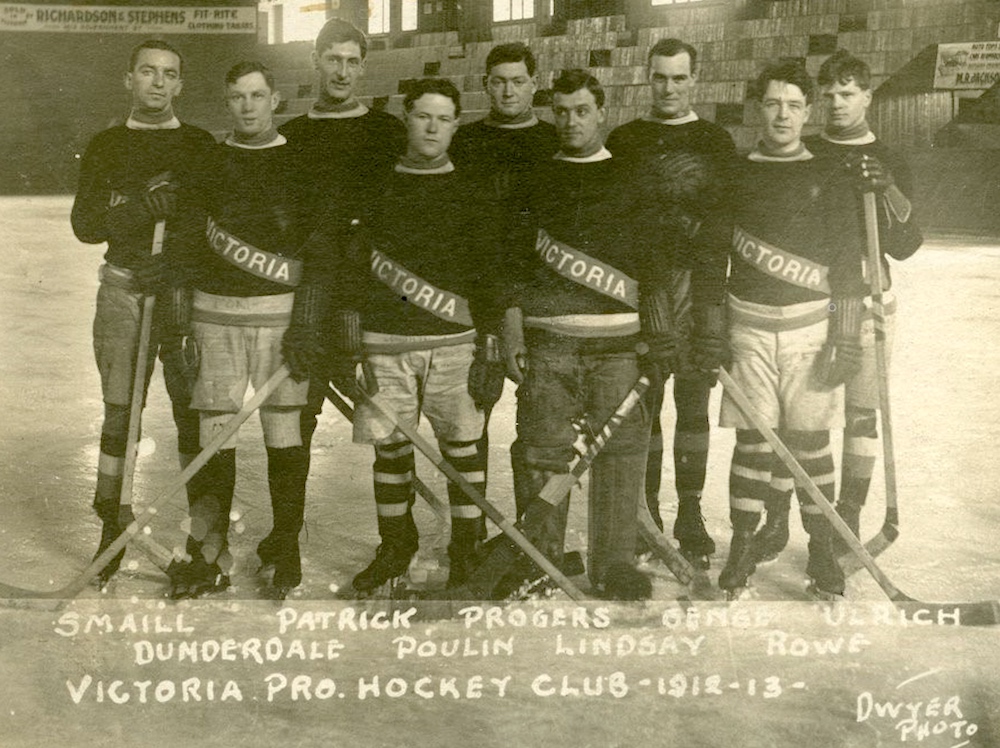

Smaill’s career at the highest levels of hockey lasted from the winter of 1904–05 through 1915–16. He played mainly with the Montreal Wanderers, Ottawa Senators, and Cobalt Silver Kings of the National Hockey Association (forerunner to the NHL), and with the Victoria Aristocrats of the Pacific Coast Hockey Association. He played both forward and defense and had a couple of decently high-scoring seasons in his early days. He helped the Wanderers win the Stanley Cup in 1908, and Victoria to victory over the Stanley Cup champion Quebec Bulldogs in a “world championship” exhibition series in 1913. Still, he was probably more of a support player than a true Hall of Fame star — although he seems no less worthy of selection than some of the other inductees from his playing days.

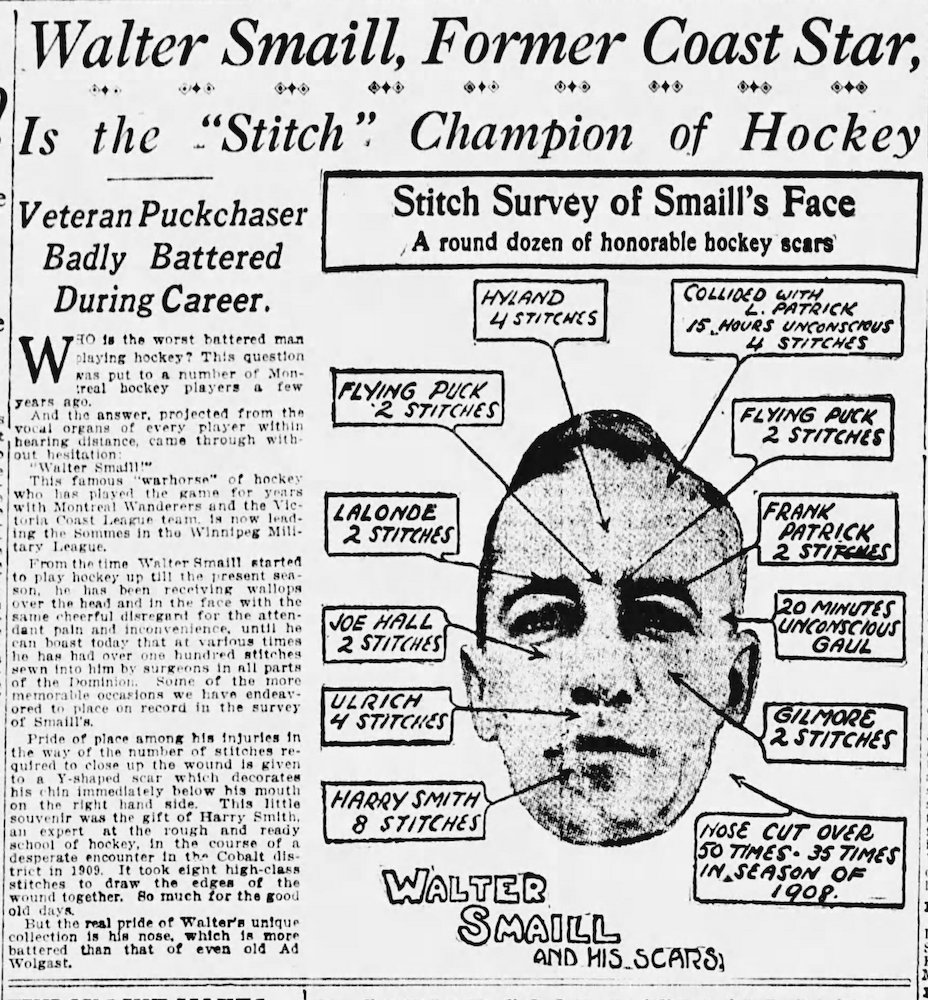

One thing, it seems, most other players of his era agreed on was that Smaill was “the worst battered man playing hockey.” In a story that made the rounds in at least a few Canadian newspapers in January and February of 1918, Smaill’s numerous cuts and scars over the course of his career — “he has over one hundred stitches sewn into him by surgeons in all parts of the Dominion” — were detailed. One of the more than 50 times his nose had been cut occurred in the first game ever played in the history of the PCHA, on January 2, 1912, when he collided with future Hall of Famer Harry Hyland of the New Westminster Royals. Smaill was married six days later, and as several of the papers in Victoria, Vancouver, and Montreal that reported on the wedding noted: “[he] looked anything but the happy bridegroom with his nose all swathed up in bandages.”

The 1918 stories mention nothing of one of Smaill’s more unusual injuries/afflictions, which was detailed in the New York Telegraph on March 18, 1908, the morning after the Montreal Wanderers played the Montreal Shamrocks in New York:

Walter Smaill, who played with the Wanderers, has the distinction of being the only man in this or any other country who has a silver-plated shin bone. Vicious blows from hockey sticks in the hands of his opponents in games he has played have from time to time so battered Smaill’s right leg below the knee that he was for a time retired from the game. He sought medical aid for months, but was compelled to continue the use of crutches until he visited a prominent surgeon in Quebec. The physician told him that the hurt could be remedied if he was willing to undergo a very tedious and painful operation. He consented at once.

Suffering the most excruciating pain, he permitted the surgeon to lay bare the bones of his leg an inch at a time and bind it with thin plates of silver. The operation required more than three months to complete, but was very successful.

Back in Montreal, the Gazette repeated the story the next day, under the headline HIS SILVER SHIN, but explained the original injury had actually occurred while playing a different sport. “The foundation for the story,” said the Gazette, “is that Smaill was laid up three years ago from a kick on the leg received in a [Quebec Rugby Football Union] game against Ottawa on Atwater Park.”

The whole truth of the story is difficult to confirm, but you can see below in this article from the Montreal Star on October 23, 1906, that Smaill did hurt his shin playing football for Westmount and would likely require surgery:

While he did miss the end of the 1906 football season, which wrapped up early in November, he was out for practice with the Montreal AAA hockey team by mid December.

Ironically , Smaill suffered the worst injury of his hockey career shortly after the appearance of the newspaper articles outlining his battered career. It occurred on February 21, 1918. Technically, Smaill had retired from hockey by then.

Having spent four seasons from 1911 to 1915 playing and living in Victoria, work took Smaill to Winnipeg in the summer of 1915. Having been granted free agency by the PCHA, he returned to Montreal for the winter of 1915–16 and played for the Wanderers in the NHA. Hockey at this time was suffering during the years of World War I. Many amateur leagues shut down for the duration, and several pro teams went out of business. Not surprisingly, salaries were slashed. A Toronto Star story from December 14, 1916, notes that Smaill had once earned as much as $200 per week to play hockey (probably a $2,000 contract for 10 weeks with Cobalt during the first NHA season of 1909–10), but was being offered only $40 per week to return to the Wanderers for the 1916–17 season. He quit hockey instead, and took a full-time job working for the YMCA in Winnipeg. In the fall of 1917, Smaill was appointed secretary of the YMCA for military athletics in the Winnipeg area. “Smaill has had a vast amount of experience in sport,” reported the Winnipeg Tribune on November 20, 1917, “and should be able to provide many attractive events for the khaki boys.”

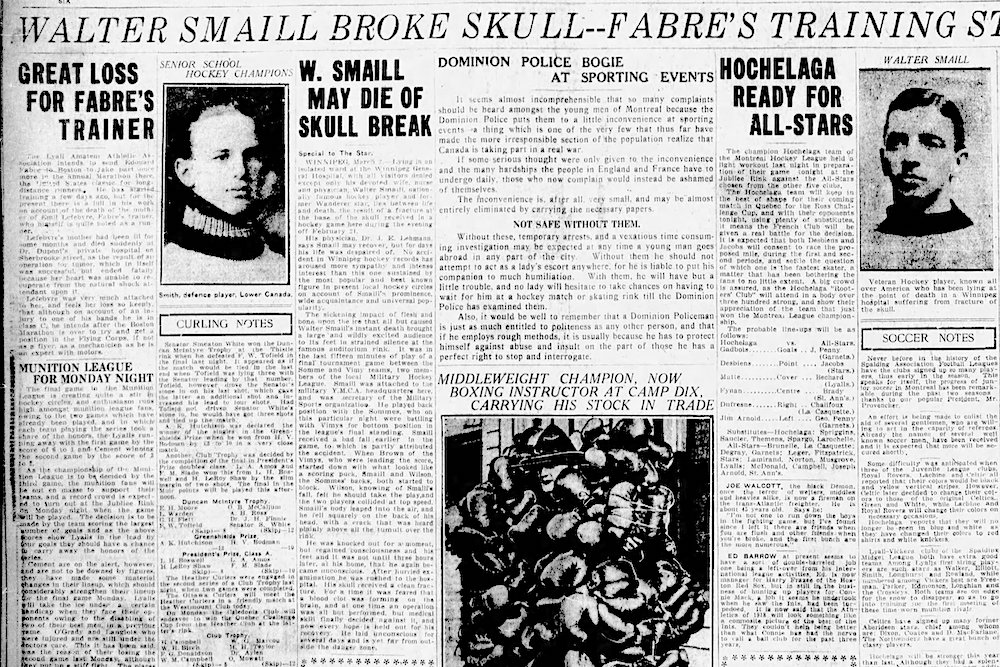

Among the sports Smaill organized was a military hockey league, with three Winnipeg teams dubbed Vimy, Ypres, and Somme. (Future Hall of Famer Dick Irvin starred for Ypres, and led the league with 29 goals in just nine games played.) Smaill returned to the the ice with the Somme, and was injured in the final game of the season. A report in the Tribune on February 22, 1918, notes only that, “in clearing an attack Walter Smaill was badly hurt in the head and was obliged to retire.” The next day’s Manitoba Free Press tells more:

The greatest anxiety prevails among Walter Smaill’s friends on account of the serious reports received from the General hospital last night of his condition. On examination his skull was found to be fractured, and he had suffered a series of convulsions during the day and was unconscious the greater part of the time; it was found that the only relief can be found in an operation of a highly dangerous character. The physicians in charge of the patient believe there is either a blood clot on the brain or a piece of the broken bone pressing upon it.

When the accident happened at the Amphitheatre rink Thursday night in the Somme-Vimy game, the final of the schedule, Smaill and [Harry] Wilson were making an attempt to stop [Cecil] Browne who was going down at a rapid gait. The two Somme players bumped into each other and Smaill was a little overbalanced when he met Browne, and he fell heavily, his head striking the ice with terrific force. Though he was able to walk from the dressing room to the ambulance he was in a much more serious condition than at first believed.

There were concerns that Smaill’s injuries might prove fatal. As it was, he would spend five weeks in hospital before (as the Winnipeg Tribune would report on March 25, 1918), “his grand physique pulled him through in good style.” Even then, it was thought he would require another two or three weeks of recovery at home. He never played hockey again.

Smaill had suffered a dangerous head injury once before, in a manner similar to the way in which hockey star Hod Stuart had been killed in the summer of 1907. On July 1, 1909, Smaill and some friends were standing on a dock in Cartierville in the North End of Montreal. A woman dropped her glasses into the river, and she asked Smaill — an expert swimmer — if he would dive in and recover them. “He was told,” reported the Montreal Gazette on July 3, 1909, “the water at this point was sixteen feet deep, and so he dived almost straight down.” But the water was only three feet deep with a rocky bottom. “The result was that Smaill hit bottom with sufficient force to stun him, and he remained for a few moments head down in the river.” His friends thought he was just fooling around, and were laughing until “he suddenly came up with his face a mass of blood and bruises…. He was badly dazed, and was helped to the shore, where he soon recovered.”

Still, with all of his sporting mishaps, perhaps the closest Smaill ever came to death was while he was helping in the construction of the Victoria Arena he would play in for four seasons. Smaill told the story to Lloyd McGown of the Montreal Daily Star for a column on February 22, 1941:

I went to the Coast to play hockey for Lester [Patrick] in 1911. I went with Skinner Poulin, Dubby Kerr and Bobby Rowe… We went out to play for $1,500, which was more than we were making here in the East…. We went out in August of 1911. The Patricks were building the rinks at Victoria and Vancouver. Both rinks went up at the same time, so we went to the contractor for jobs—Poulin, Kerr and Rowe and I. We bought canvas aprons with pockets, T-squares, chisels and hammers. We helped build the rink to play in at 50 cents and hour.

I almost fell from the roof, about a sixty-foot drop to the ground. I happened to catch a scantling [a small cross-section of lumber] and there I hung with my feet dangling over the edge. Finally they lassoed my legs and hauled me up to safety. I was sick for three days. It was that close…. [T]he sports writer of The [Victoria] Times was there. ‘Walter, I thought you were done for,’ he told me.

After that, Smaill helped install the ice-making system in the Victoria rink. (The Patrick arenas in Vancouver and Victoria were the first in Canada to feature artificial ice.) “We helped lay 15 miles of pipes,” said Smaill. “When we got them down they had a test and found about 150 leaks. We had threaded the pipe-ends the wrong way, though a plumbing inspector was supposed to be overseeing the job. We weren’t very good plumbers.”

It’s stories like these that are the reason I find hockey of this era so fascinating!

My god, the poor guy! What a trooper. I can see why you admire him.

Injury stories — especially Eddie Shore versions — fascinate me.

But this guy has to be the all-time trooper’s trouper.

Thanks for another gem, Eric.

What a great story!!!

Wow! Walter Smaill was some sort of ‘Super-Hero’ of his time!

What a amazing man & amazing life story Eric!

Sherri-Ellen & BellaDharma

Thank you for another detailed and interesting insight, Eric.

Your story prompted me to do some research about his son, Douglas Smaill who joined the Black Watch immediately after graduating from high school in Montreal and was killed during the Battle of Scheldt in The Netherlands which occurred October 2-November 8 1944. He was officially declared dead on February 28, 1945. With 12,873 casualties (killed, wounded, or missing), half of who were Canadians, it is hardly surprising that the administrative record-keeping took some time to get caught up.

Lest we forget.

Thanks Eric….another fascinating story. He probably had several concussions before anyone knew what a concussion was. Keep writing these interesting stories.

Diving into three feet of water….yikes.

Great story Eric!!!!

Can’t believe this guy made it to 86, silver shin and all. Great story!

Again, your research is most impressive!!!

The guy took more than his share of pain. Not a great idea to dive when you are not aware of the depth – lucky he survived.

I was wondering about that too. Given that he was supposed to be a great swimmer (and a sailor) you’d think he would have known better!