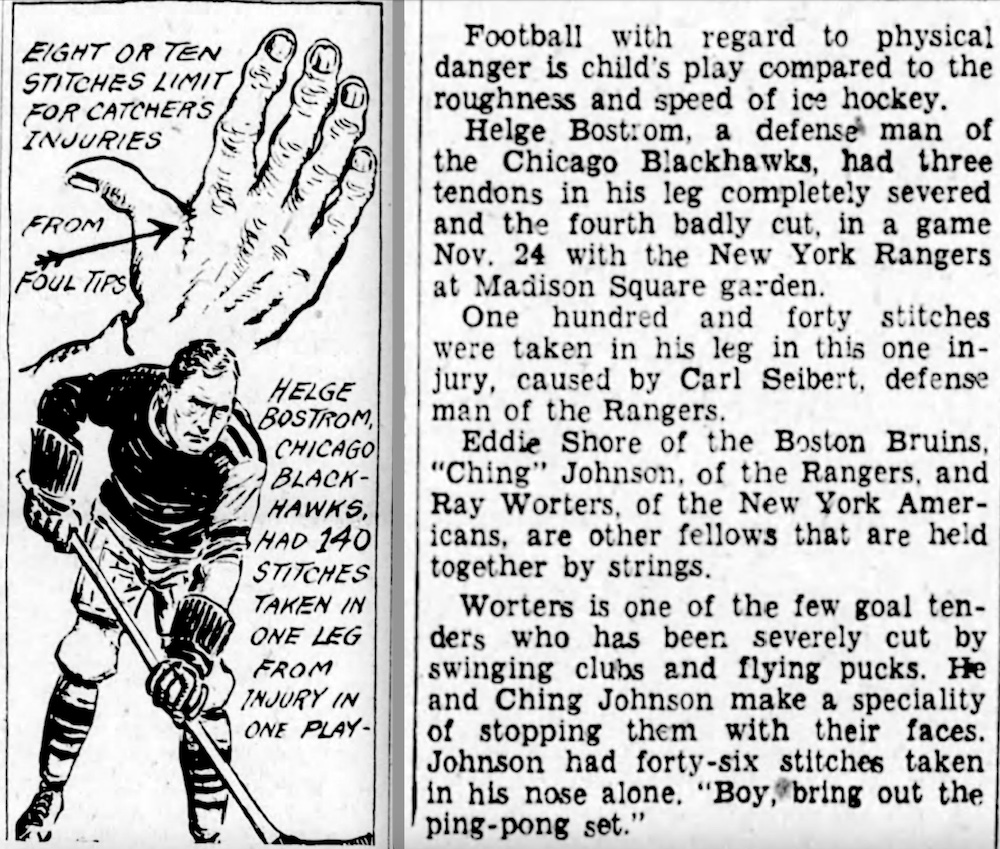

This is, I guess, a sequel of sorts to my recent story about Walter Smaill. When finishing up my research for that one, I came across a cartoon and a brief story in the Calgary Herald from February 27, 1932. It reported on Helge Bostrom of the Chicago Black Hawks (two words in those days; not Blackhawks) who had recently been cut for 140 stitches. Having previously suffered some 100 stitches from various minor injuries, Bostrom was now considered hockey’s Most-Stitched Player. “The former title holder,” the story reported, “… was Walter Smaill, of the old Montreal Wanderers, who suffered 168 in his career.”

The 1931–32 season marked Helge Bostrom’s third year in the NHL. He’d just turned 36 years old when he joined the Black Hawks in January of 1930, and had played plenty of hockey before that. His earliest records place him in military and patriotic hockey leagues in his home town of Winnipeg (some sources say he was born in Gimli, Manitoba), playing for the Ypres team against Walter Smaill’s Somme in 1917–18. After a year of military service in England and France, Bostrom played two seasons of amateur hockey with the Moose Jaw Maple Leafs in Saskatchewan before turning pro with the Edmonton Eskimos of the Western Canada Hockey League during the 1921–22 season.

Mostly a hard-hitting defensemen, but also something of a penalty shot specialist (in those days, penalty shots were taken from a fixed point, so a powerful blast was key), Bostrom helped Edmonton to a WCHL title in 1922–23, before a Stanley Cup loss to the Ottawa Senators. He spent the next four seasons with the Vancouver Maroons before top-level pro hockey collapsed in the west after the 1925–26 season. He then played three-plus seasons with the Minneapolis Millers of the American Hockey Association before finally entering the NHL.

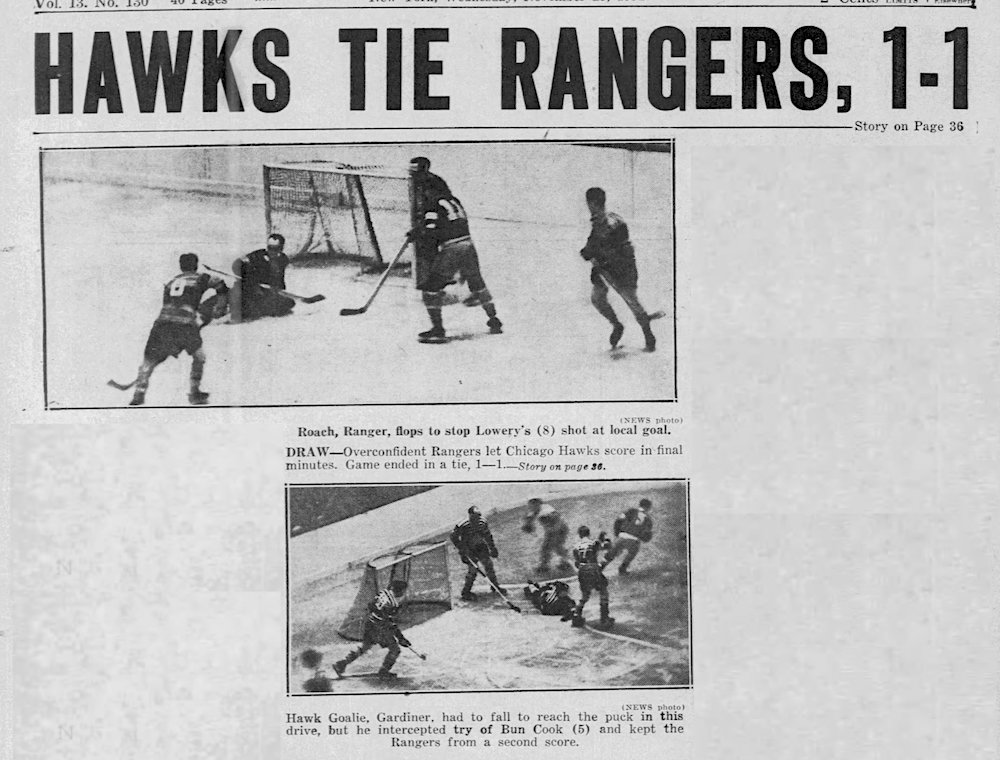

As to the injury in question, Bostrom was hurt during the second period of a 1–1 tie with the New York Rangers at Madison Square Garden on November 24, 1931. There’s not a lot of details about the injury in most game stories. The New York Times says nothing at all, noting only that Bostrom (they spell it Bostrum — as many papers did) was in the penalty box when the Rangers scored their only goal late in the first period. (Chicago tied the game late in the third period.) The New York Daily News reports, “The second session was marked only by an injury to Helge Bostrum … who cut a tendon in his leg in a mixup with [Earl] Seibert.”

Of the newspapers I’ve been able to check, the Montreal Gazette and the Brooklyn Times-Union had the most to say about Bostrom’s injury in their game reports the next day. “Early in the second period,” says the Gazette, “Bostrum was assisted off the ice after colliding heavily with Seibert and it was afterwards announced that the burly defence man had cut a tendon in his left leg.” The account in the Brooklyn paper says, “Bostrum was injured by a skate when he checked Seibert in the second period.”

The Times-Union story says it was Bostrom’s instep that was cut — though most stories later would say his ankle — “and the discovery of a severed tendon means that he will be lost to the team for several weeks.” The Brooklyn paper further notes that “Bostrum’s foot was to be operated on today.” A later story in the Chicago Tribune on December 6, 1931, reports that Bostrom was still in New York’s Polyclinic hospital when his Black Hawks teammates visited him there on a return trip to New York prior to a game that night against the Americans. The operation was likely performed there, as Madison Square Garden and New York Rangers team doctor Henry O. Clauss Jr. was a member of the surgical staff at the Polyclinic.

In recalling the injury in the New York Times on January 4, 1932, John Kieran writes: “Remember the night Helge Bostrum of the Hawks was hurt at the Garden? Ankle cut by Earl Seibert’s skate. Didn’t seem so bad as he hobbled off the ice, but when Dr. Clauss checked up, three of the four tendons were cut and before they got through patching him up, they took exactly 142 stitches to pull him together.” (Stories in other newspapers put the number of stitches at 140 or 145, but the Minneapolis Star-Tribune asked “What’s [a] Mere 400 Stitches” in a headline above a story about Bostrom on February 12, 1932.)

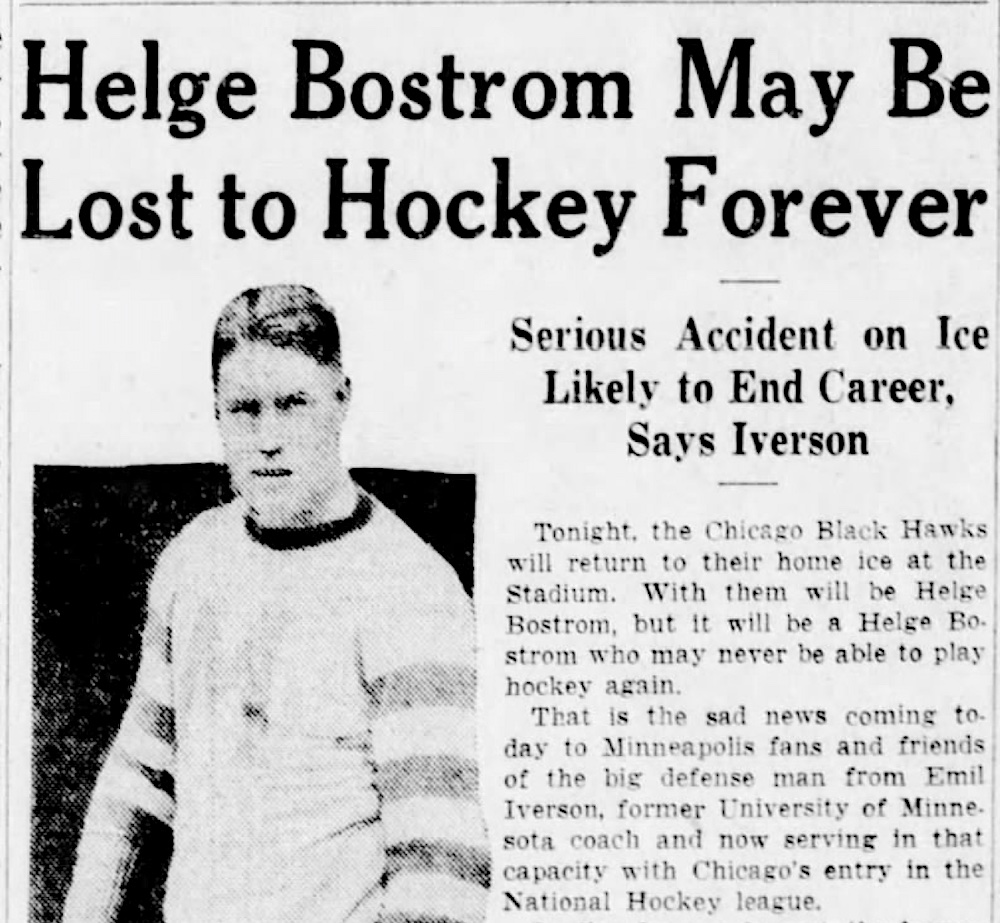

Despite the early report that he would be sidelined for several weeks, word soon was Bostrom might never play hockey again. That was certainly a fear Black Hawks coach Emil Iverson expressed in a story reported in The Minneapolis Star on December 11, 1931. A story in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle a month later, on January 10, 1932, explained more:

It was cruel the way the accident happened…Earl Seibert just stumbled over the half-prone Helge in a harmless-looking mixup around center ice. But the tip of Seibert’s skate bit like a rapier down to the bone, slashing tendon after tendon. The cut wasn’t more than an inch and a half long and the surgeons had to lengthen it, reach up and pull down the muscles, and fasten them. When they knit together Bostrom will be able to walk without even the semblance of a limp, but the repairs may not be able to hold under the strain of those sudden stops in hockey.

Apparently — according to a story in The Minneapolis Journal six years later (February 17, 1938) — things were so dire that Bostrom was receiving ads from casket owners (casket makers?) while he was in the Polyclinic hospital. But Helge was having none of it!

By early February of 1932, Bostrom was in the Twin Cities and skating again. “Out of hockey, nothing,” he roared for an Associated Press story out of St. Paul that appeared in papers on February 12. “I’ll be playing again before the season’s over.” The day before, The Minneapolis Star quoted him saying, “Whoever said I wouldn’t be able to play hockey again is crazier than the hombre who insists that the Hawks won’t be in the Stanley Cup playoffs. Why, I expect to be in those same playoffs myself.”

And he was.

Maybe.

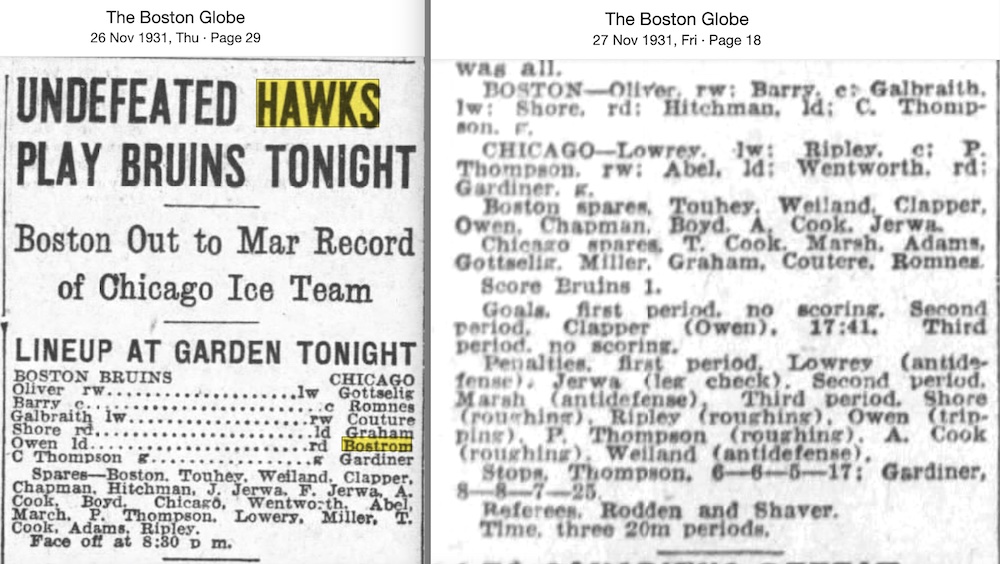

Bostrom was back in action on February 17, 1932, when the Black Hawks hosted the Canadiens in Chicago. According to the NHL game logs, he played in seven more games after that, but then missed the next five, before returning for two playoff games against the Toronto Maple Leafs. The strange thing is, the newspaper accounts of games late that season don’t always match up with the NHL records. And for sure, those records must have it wrong when they show Bostrom playing in Boston on November 26, 1931 — two days after the injury. It seems highly unlike that he was hurt that badly on November 24, had surgery on November 25, played in Boston on November 26, and then returned to New York to spend another week or more in hospital there.

Regardless of how many games Bostrom actually played in 1931–32, he was not only back with the Black Hawks for the 1932–33 season, he was named the team’s new captain. But that December, he was traded to the St. Paul Greyhounds of the American Hockey Association, where he would be their player-coach. Bostrom continued to play in minor league cities through the 1935–36 season, finishing up with the Kansas City Greyhounds, whom he would later coach for two years from 1937 through 1939.

In the image on the right, Bostrom’s name does not appear in the summary of the game.

And tough as he must have been, it seems Helge Bostrom may have done more for the sport of figure skating than hockey. According to Roy Shipstead, one of the founders of the Ice Follies, Bostrom gave the struggling Roy, his older brother Eddie, and their partner Oscar Johnson, a significant boost. Shipstead told the story to Vern De Geer of the Gazette for his column on February 1, 1961 while in Montreal for the Canadian Figure Skating Championship.

It wasn’t easy. We were fancy skating bugs in St. Paul when most of our neighborhood pals were busy on the hockey rink. Most of the hockey players were coming in from Western Canada. They were making good money and it looked like a good career for Minnesota boys. But it was one of those imports who persuaded me to follow Eddie and Oscar in the ice skating entertainment business.

Helge Bostrom, a fun-loving Norwegian friend of ours from Winnipeg, recommended us to an entertainment booker at the Chicago Sherman Hotel’s famous College Inn. That was in 1935. We were given four weeks trial and stayed for 16 months. It was the success of this run that started us in the travelling carnival routine the next year. And we’ve been at it ever since. We’ll be forever grateful to Helge for this.

One wonderful story piled on the other. But it demonstrated how dangerous hockey was– and still is and, to me, equally frightening was the sliced tendon suffered by Rocket Richard late in his career. It led to total use of tendon guards. Miraculously, Rocket returned and won either one or two Cups after his recovery. One of Eric’s best, including the back page headline in the Daily News that showed how hockey had won attention in NY.

Wow. I know that all sports, yes, all sports can be lethal to the players. I recall a friend of mine in high school who was a dancer. Her training was in classical ballet, and then she added jazz as well as toe tapping, with is wearing pointes with taps on them. She was great, and she had won many contests at the CNE, and other venues. But in her last year of high school she had a dreadful accident because the dance floor had not be cleaned properly. She fell, landing in the pit with the orchestra, and beside breaking an arm, she suffered huge gashes on both legs, her chin, and the arm that wasn’t broken. She was in hospital for a few days, but I remember she was a “proud” recipient of over 200 stitches and the staff of the hospital gave her a blue ribbon when she was discharged. She did return to dancing about 6 months later, always making certain that the dance floor was thoroughly clean and dry! So sports people are not the only ones who suffer from injuries.

Yipes… mucho dangeroso.

Thanks, Eric

Great profile and research on Bostrom. As you say the research has a way of cascading from one person’s story or event into another, Smaill to Bostrom.

Which leads us to Jimmy Thompson, the artist and writer of your lead article. The man behind the byline.

I wrote 177 words on Thompson in my original manuscript of Picturing the Game. His unique hockey story deserved much more attention and, frankly, I blew it.

While I kept his marvelous illustration of Conn Smythe and his big win at Coronation Stakes in 1930, I got a brain cramp when I chopped my ms from 181,550 words to 78,000 words.

Thompson got the cut, a greater regret of mine than many others who didn’t make it.

Please tell me you will eventually write a book on the Montreal Wanderers or Ottawa Silver Seven?

I’m glad I never wanted to play hockey! (LOL)

Linda