Well, the big blizzard sort of skipped New York, though it hit pretty hard elsewhere. And it’s supposed to warm up – albeit briefly! – around here today. It is only the 28th of January, but pitchers and catchers begin to report for spring training in three weeks, so summer can’t be too far away! Hockey may be where my head is much of the year, but baseball is where my heart is … and, sometimes, you get to tell one story that combines both sports!

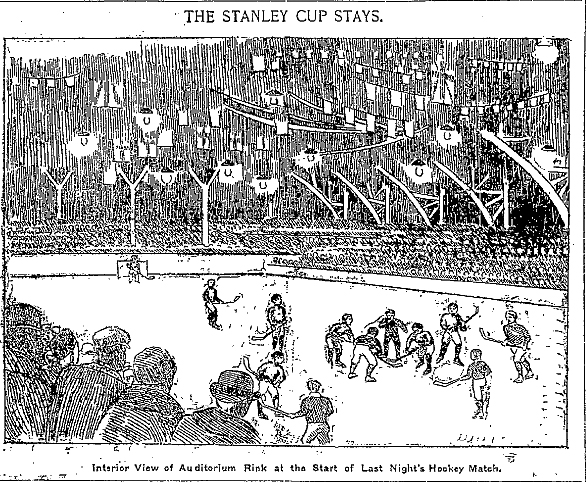

In late January of 1926, the Toronto Maple Leafs baseball club was already hard at work preparing for the International League season. This would be a big year for Toronto baseball. The team was leaving its old park on Hanlan’s Point and moving into the brand new Maple Leaf Stadium at the foot of Bathurst, near Fleet Street. (Behind what is now the Tip Top Tailor lofts near the Canadian National Exhibition grounds.) With a seating capacity of 20,000 the new stadium was considered the most modern facility in the minor leagues. Baltimore had won the International League pennant every year from 1919 to 1925, but in 1926, Toronto had a record of 109-57 to take the league title. They then swept five straight games from Louisville of the American Association to win the best-of-nine Junior World Series.

But all of this was still nine months into the future on January 29, 1926, when Maple Leafs manager Dan Howley signed a couple of locals boys for his team. Both also happened to be NHL stars: Cecil “Babe” Dye and Lionel Conacher.

Babe Dye was one of the top scorers in the NHL during the 1920s and a future Hall of Famer, but he was also a minor league baseball star with a couple of offers from Major League teams over the years. He had his best baseball seasons with the Buffalo Bisons from 1922 to 1925, but injuries suffered in the NHL seemed to take their toll and he had a poor season with the baseball Maple Leafs in 1926. Released halfway through the schedule, he finished the year with Baltimore and never played baseball again.

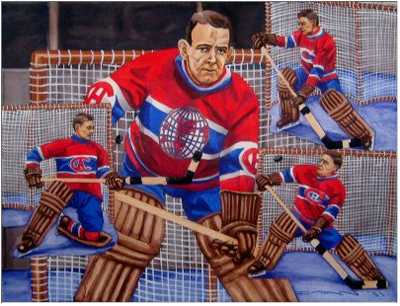

Lionel Conacher was a great all-around athlete who was best known as a lacrosse and football player when he was younger, but willed himself to become a Hall of Fame hockey player because that’s where the money was in Canadian sports. Conacher also boxed and wrestled, but baseball was only a sport he’d dabbled in around the Toronto sandlots.

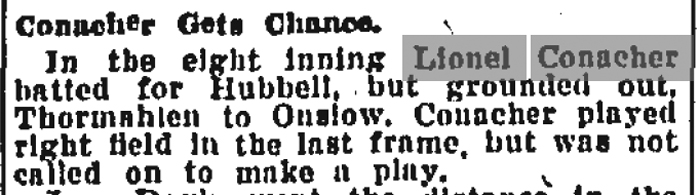

Still, according to the Toronto Star, Conacher’s contract with the Maple Leafs stipulated that he had to be carried for the entire season and could not be traded or sold. Having him on the roster meant added publicity, but Manager Howley was said to be sure that Conacher would make good. Given that Toronto had a working relationship with the Detroit Tigers and shared a spring training facility with them in Augusta, Georgia, it was hoped that Ty Cobb would help to make a star ballplayer out of Canada’s future Athlete of the Half-Century. Conacher saw action in the Maple Leafs outfield with Dye during spring training, but was pretty much glued to the bench once the season got under way. What statistics there are show him batting only three times all year. (In a quick search, I could only find him batting once, grounding out as a pinch hitter for future Hall of Fame pitcher Carl Hubbell in the eighth inning of a game on June 27.)

It seems unlikely that Conacher actually spent the entire season with the Maple Leafs, as a Toronto Star story on August 14 discusses him being on a trip to Sudbury with his wife and a brother and fishing with future Hockey Hall of Famer Shorty Green. Later, Conacher was playing lacrosse in St. Catharines on September 19 during the final weekend of the International League season.

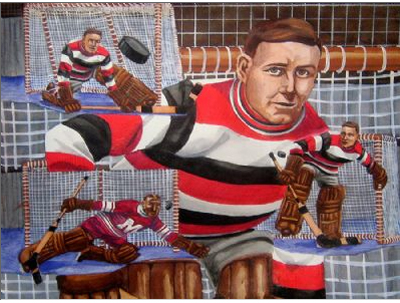

Both Conacher and Dye made their biggest splash of the baseball season on June 19, 1926, when the Maple Leafs were on the road but they were allowed to return to Toronto for an exhibition game at Maple Leaf Stadium between the Toronto Semi Pros and Buffalo’s Pullman Colored Giants. The Semi Pros featured a third future Hockey Hall of Famer in Conacher’s buddy and longtime teammate Roy Worters. The baseball team also had two other Conacher-Worters hockey teammates in Duke McCurry and Jess Spring and another hockey player in Chris Speyer. Conacher had a single and a triple in this game, and made two sensational catches in the outfield, but the Colored Giants rallied for an 11-10 victory.