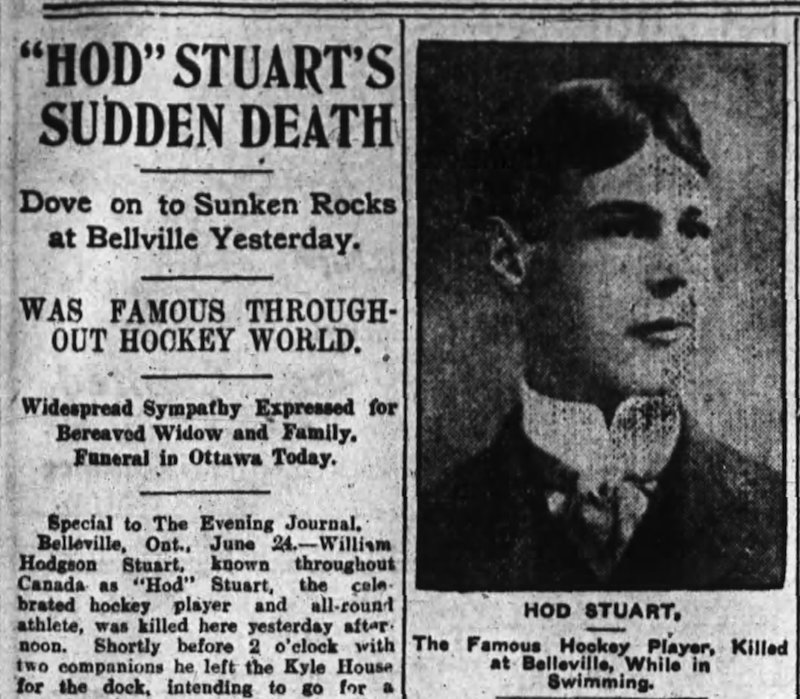

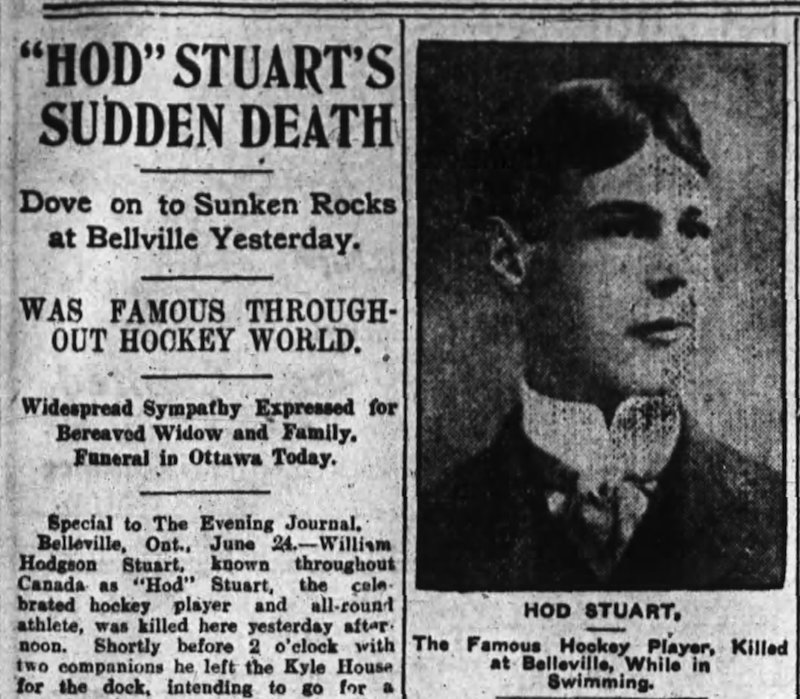

On June 23, 1907, Hod Stuart died at the height of his hockey career. He was 28 years old. Some of you reading this will recognize his name right away. Others won’t. But 108 years ago today, news of his death would have been like hearing that Sidney Crosby or Jonathan Toews had just been killed.

Hod Stuart was a defensemen (a cover point in his day), so a better comparison might be made to Drew Doughty, P.K. Subban, or Erik Karlsson, one of whom will win the Norris Trophy tomorrow as this past season’s best NHL defender. Given his status as the game’s highest-paid player, perhaps Stuart was most like Nashville’s Shea Weber – although during the 1906-07 season when hockey players were first allowed to earn salaries in Canada, you’d have to add a lot more zeroes before Stuart’s salary (which was somewhere between $1,200 and $1,500) matched the $14 million Weber makes.

William Hodgson Stuart, the son of William Stuart and Rachel Hodgson, was born in Ottawa on February 20, 1879. His father was a well-respected contractor and the captain of the Ottawa Capitals lacrosse team. Young Hod played football and hockey in Ottawa at the end of the 1890s, but moved to Quebec City in 1900 on a contracting job for his father. He played hockey there too, and met his future wife, Marguerite Cecilia Loughlin, whom he married in 1901. By 1907, they had two young children.

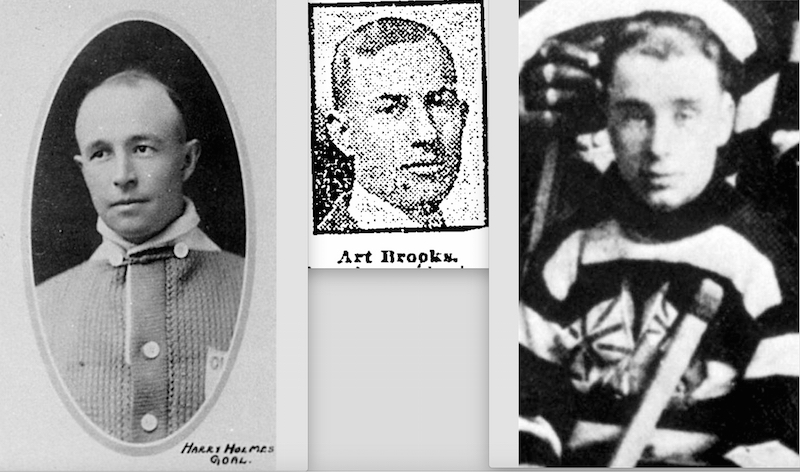

Hod Stuart had yet to emerge as a hockey star while playing in Ottawa and Quebec, but did so quickly after 1902 when he began to play in the United States – where players were already allowed to earn a salary. Canadian fans needed convincing when Stuart left Pittsburgh in late December of 1906 to play for the Montreal Wanderers, but his play was outstanding and the press reports were just as glowing. Late in his life, Art Ross would say that Hod Stuart was the only defenseman he’d ever seen that was in a class with Eddie Shore.

Despite what many sources say, Stuart was not yet with the Wanderers when they defeated a team from New Glasgow, Nova Scotia in a preseason Stanley Cup challenge at the end of December. He joined the team in time for its first regular-season game on January 2, 1907 and starred in the Wanderers’ Stanley Cup series with the Kenora Thistles two weeks later. The Thistles won, but the Wanderers bounced back to finish their 10-game season with a perfect 10-0 record and Stuart was a big part of their winning back the Cup in a rematch in Kenora at the end of March.

After the hockey season, Stuart returned to Ottawa but was soon at work for his father’s construction company overseeing a building project in Belleville, Ontario. On a leisurely Sunday, he spent the morning canoeing with friends. In the heat of the day around 3 o’clock, they returned to the waterfront. Hod was a strong swimmer, and he jumped in from the Grand Junction dock to cool off, swimming about a quarter-mile to a nearby lighthouse.

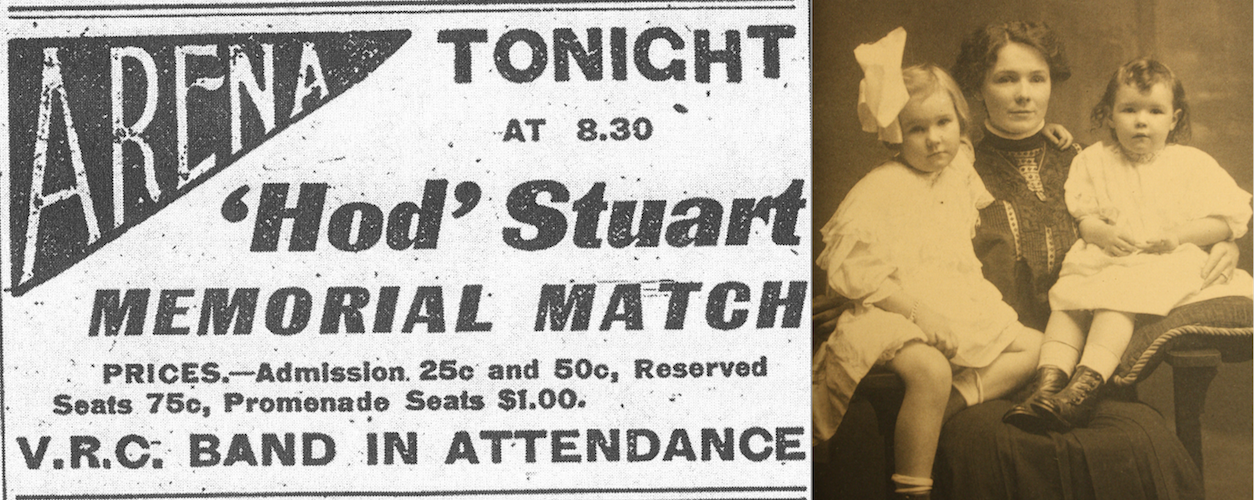

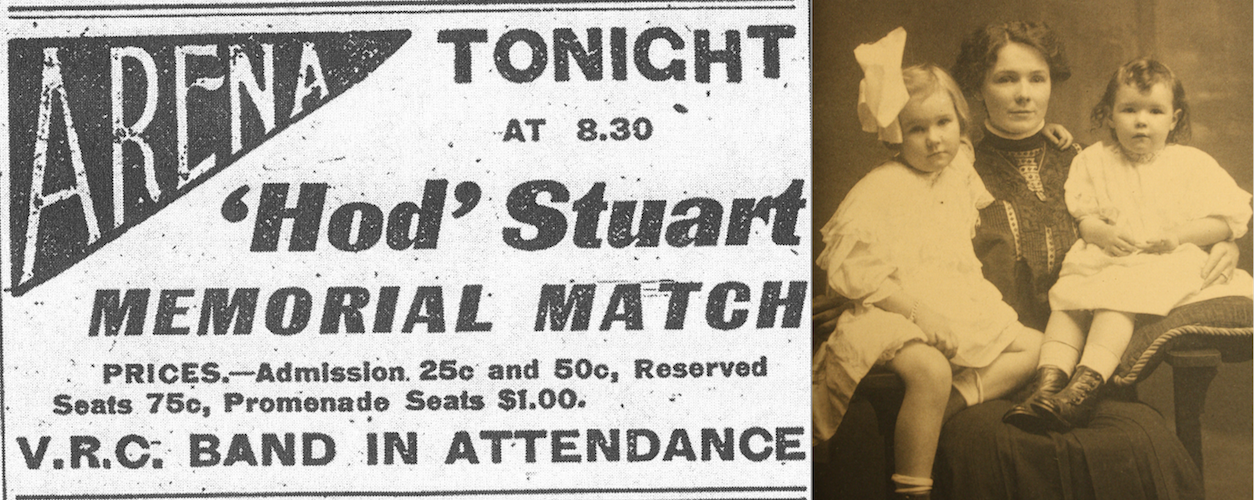

Hod Stuart’s wife and daughters, circa 1910, courtesy of johnnysgirl668 on Ancestry.com

There was a small platform around the lighthouse, about six or eight feet above the water, and those watching from the dock saw Stuart climb up and rest for a few minutes before diving in again. He didn’t re-surface. Unaware of how shallow it was in certain places around the lighthouse, Stuart struck his head on a jagged rock just two feet below the waterline. He suffered a fractured skull and a broken neck, and was said to have died instantly. On January 2, 1908, the Wanderers defeated a team of all-stars in the Hod Stuart Memorial Game, which raised just over $2,000 for Stuart’s wife and daughters. In 1945, he was among the first inductees into the Hockey Hall of Fame.

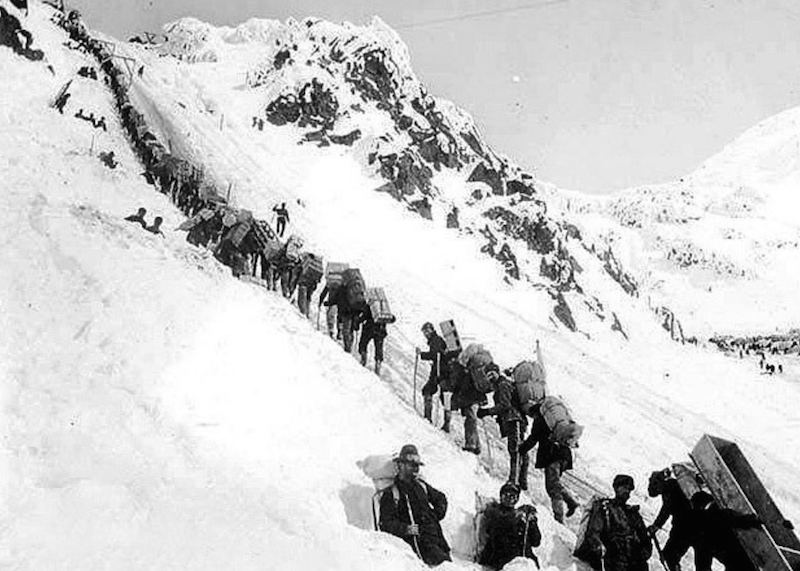

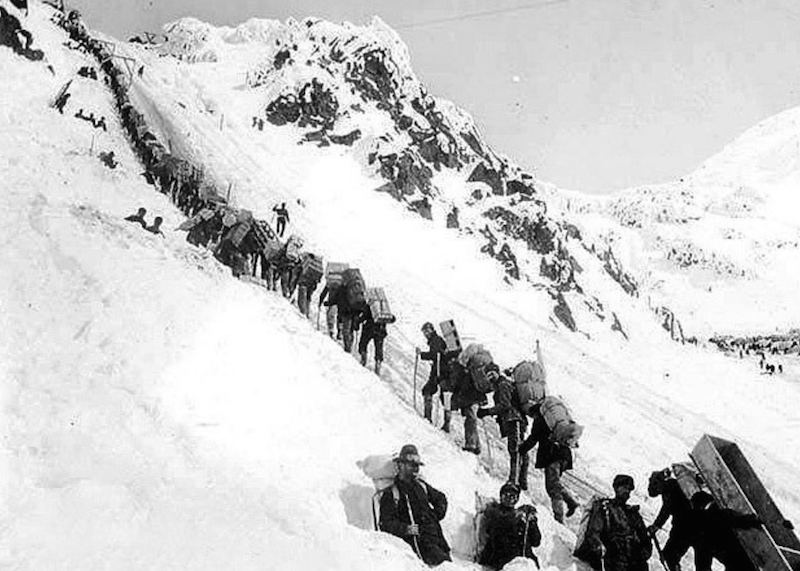

The story of Hod Stuart’s death is what I intended to write about today, but in researching his life I came across something pretty amazing. In the spring of 1897, when he was just 18 years old, Stuart left Ottawa with another local boy, sponsored by a group that included Hod’s father, to seek his fortune in the Klondike, where gold had been discovered during the summer of 1896.

As I wrote last week about the Spanish-American War, the Klondike Gold Rush is among my many wide-but-not-deep historical interests, and in a letter written to his father on May 31, 1897 (as reported in the Ottawa Journal on July 27), Hod rhymes off many familiar names:

“We left Dyea, an Indian village, Sunday…. We towed all the stuff up the river seven miles and then packed it to Sheep’s Camp…. A beautiful time we had I can tell you, climbing hills with fifty pounds on our backs…. We left Sheep’s Camp next morning at four o’clock, and reached the summit at half-past seven…. The Chilkat Pass [note: though the Chilkat Pass was a route to the Klondike, this is likely a misspelling of the more famous Chilkoot Pass, which was just beyond Sheep Camp] is not a pass at all, but a climb right over the mountains…. It was an awful climb – an angle of about fifty-five degrees. We could keep our hands touching the trail all the way up. It was blowing and snowing…”

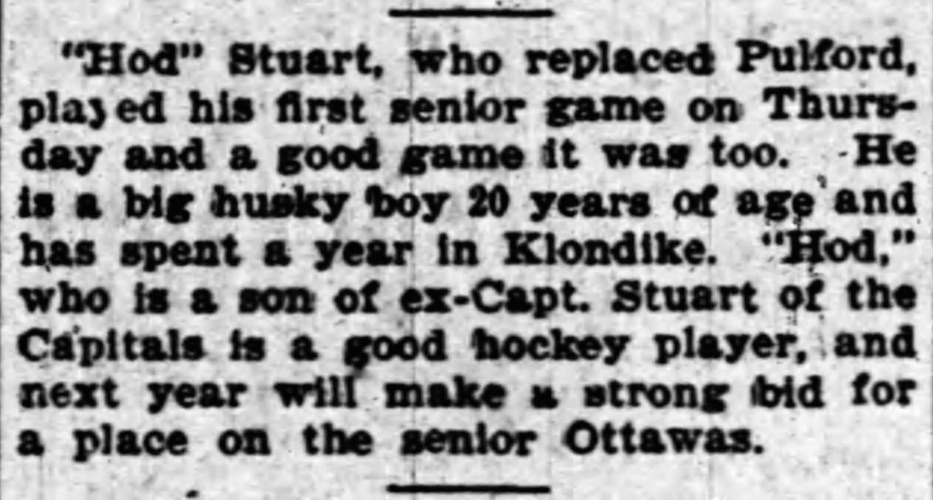

Another letter, written on June 28, appears in the Journal on October 12, but there’s not much news after that. However, on April 7, 1898, the Journal notes that Hod was among the first Ottawa parties in the gold fields, and that his father “has learned from time to time that his son has been doing well.” Astoundingly, William Stuart had left for the Klondike the night before, having contracted to build the Bank of Commerce building in Dawson City. By September of 1898, father and son were back in Ottawa. Hod failed to seek his fortune in gold, but soon found fame as an athlete.

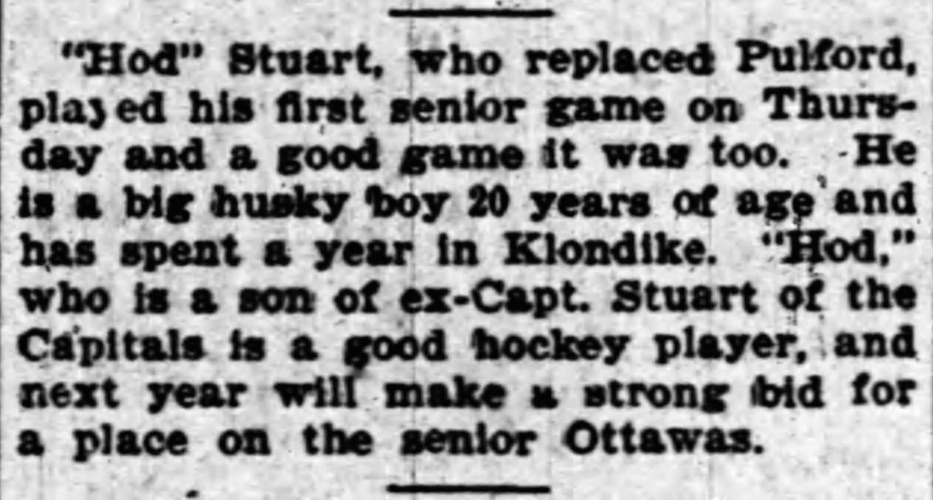

Pulford is Hockey Hall of Famer Harvey Pulford, although this clip refers to Hod Stuart’s senior football debut with the Ottawa Rough Riders on Thursday, November 24, 1898.