A while ago on this web site, I mentioned my interest in the early history of hockey broadcasts on the radio. Mostly, that relates to the very first broadcasts in 1923 and trying to uncover if there’s anything earlier than the known broadcasts from Toronto that February. Well, this doesn’t pertain to that, but I did find it interesting.

With ratings down all season for hockey broadcasts on Rogers Sportsnet, and as the playoff ratings are said to be taking a huge hit with no Canadian teams involved, let’s take a look back to when national hockey broadcasts began.

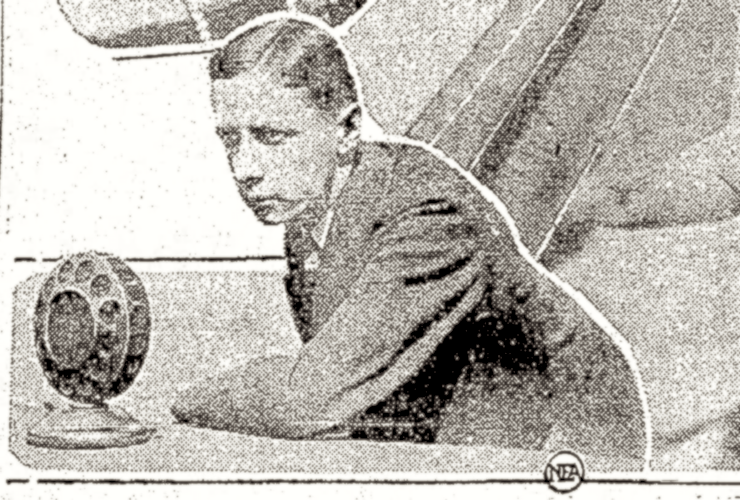

This picture of Foster Hewitt appeared in a story in

The Sunday Times-Signal of Zanesville, Ohio, on September 2, 1928.

The first national hockey broadcasts in Canada have long been attributed to the nationwide hookup for the opening game from Maple Leaf Gardens on November 12, 1931. Some sources point to the General Motors Saturday night broadcasts that began in January of 1933 and were later taken over by Imperial Oil. These were the roots of Hockey Night in Canada.

Turns out, however, that the first national broadcasts (much like the earliest broadcasts in 1923) were actually made from the Arena Gardens on Mutual Street. Fittingly, it was a game between the Toronto Maple Leafs and the Montreal Canadiens. The date was January 17, 1929 – almost three years before the opening of Maple Leaf Gardens.

Ironically, given radio station CFCA was owned by the Toronto Star, I recently stumbled across word of this in the rival Globe. On January 8, 1929, Globe sportswriter Bert Perry noted at the end of his column:

“When the Montreal Canadiens make their second visit of the season here on Jan. 17 the game will be broadcast over the Canadian National Broadcasting Company’s chain of stations from Halifax to Vancouver. It will be the first time that a Dominion-wide hook-up on a hockey game has been tried in Canada. Some fifteen Canadian stations will relay the play-by-play account to every corner of the country. The fans in Halifax, Edmonton and Vancouver will get the details right from the Arena Gardens as clearly as Toronto listeners-in.”

When W.A. Hewitt – father of Foster – mentioned the story a week later in the Toronto Star, he had more (and slightly different) details:

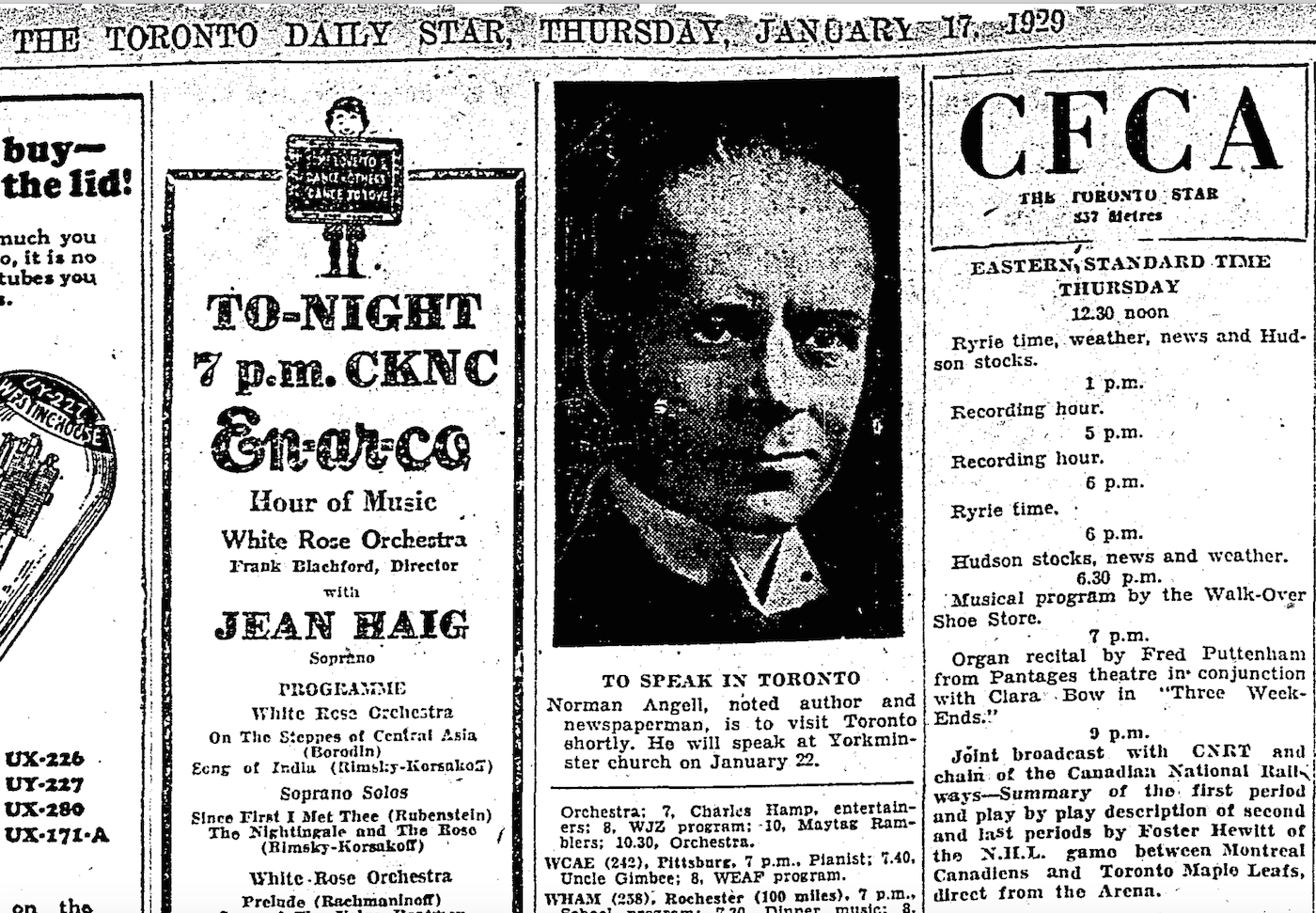

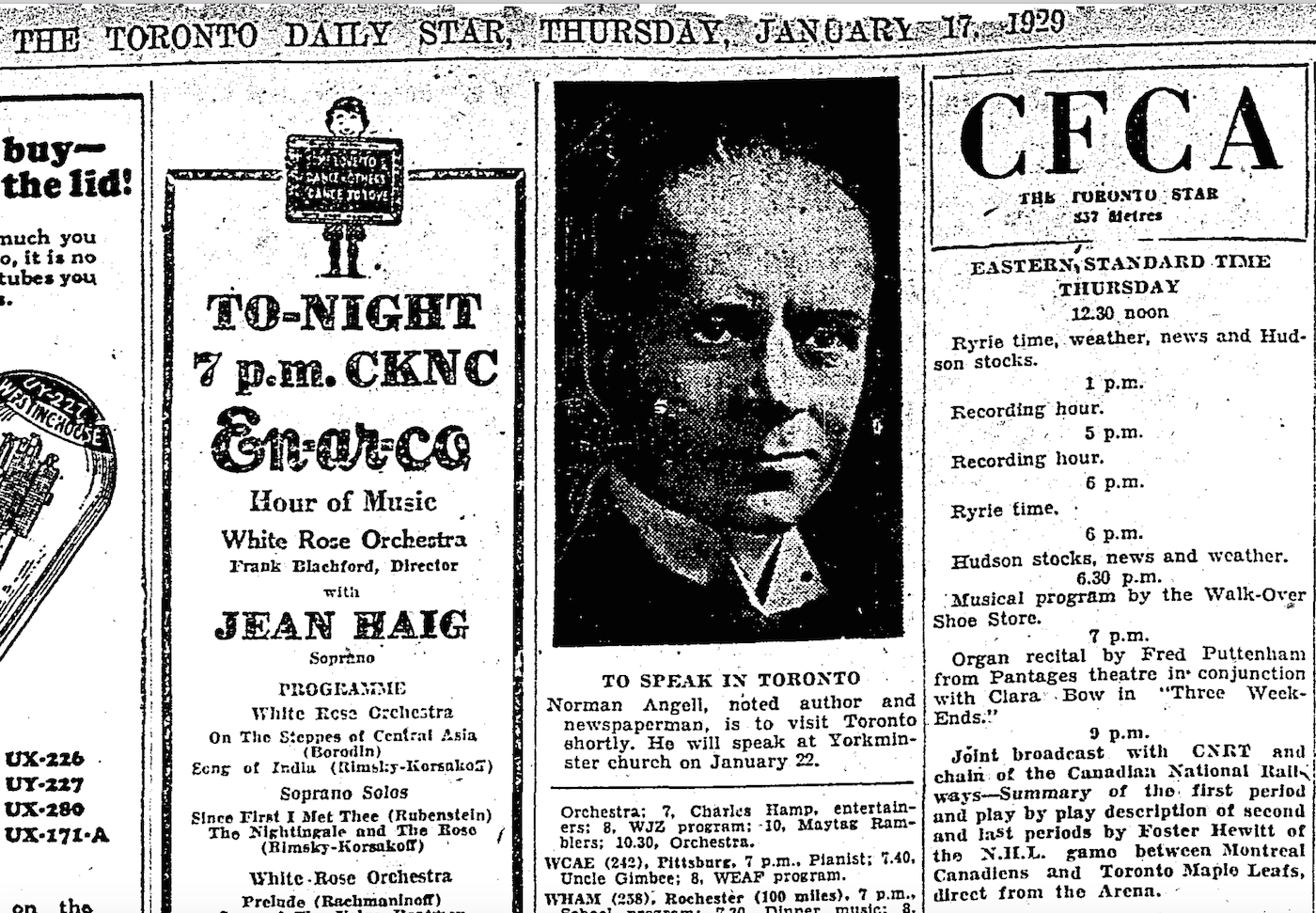

“A joint broadcast of unusual interest to Canadian hockey fans will be held on Thursday night of this week when the Maple Leafs-Canadien NHL game will be sent out on the air from Arena Gardens, Toronto. The broadcast is to be given under the joint auspices of the Toronto Daily Star and the Canadian National Railways over Stations CFCA of the Toronto Daily Star at Toronto and the Canadian National Railway’s chain of stations at Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa, Toronto and Winnipeg with CJGX, the Winnipeg Grain Exchange station at Yorkton, Saskatchewan. Foster Hewitt will be at the microphone. This will be the first time that a hockey broadcast of such magnitude has been attempted and the hook-up will interest hockey and radio fans in all parts of Canada.”

Foster Hewitt began his nationwide broadcast at 9 o’clock in Toronto.

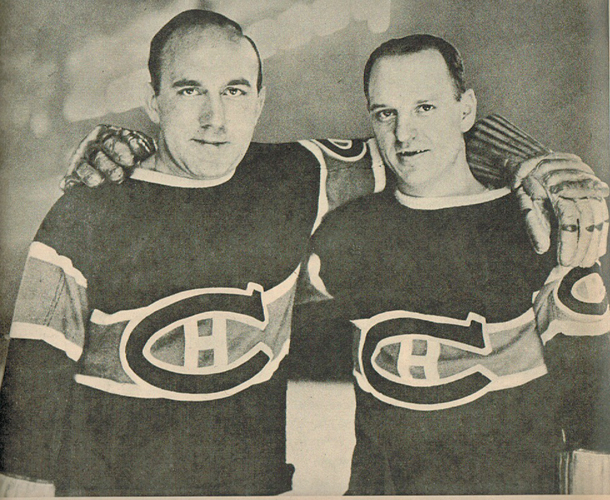

The Leafs and Canadiens ended up tied after three periods, and when 10 minutes of overtime settled nothing, they skated off with a 1–1 tie. In one story on the sports pages of the Star, the game was described as “dull for the most part, with both goals coming in the first four minutes of the second period.” (Danny Cox, assisted by Hap Day, scored for Toronto; Sylvio Mantha for Montreal. Howie Morenz was out with an injury.) A story just after the Radio page noted that Hewitt, “described the game in a graphic way.”

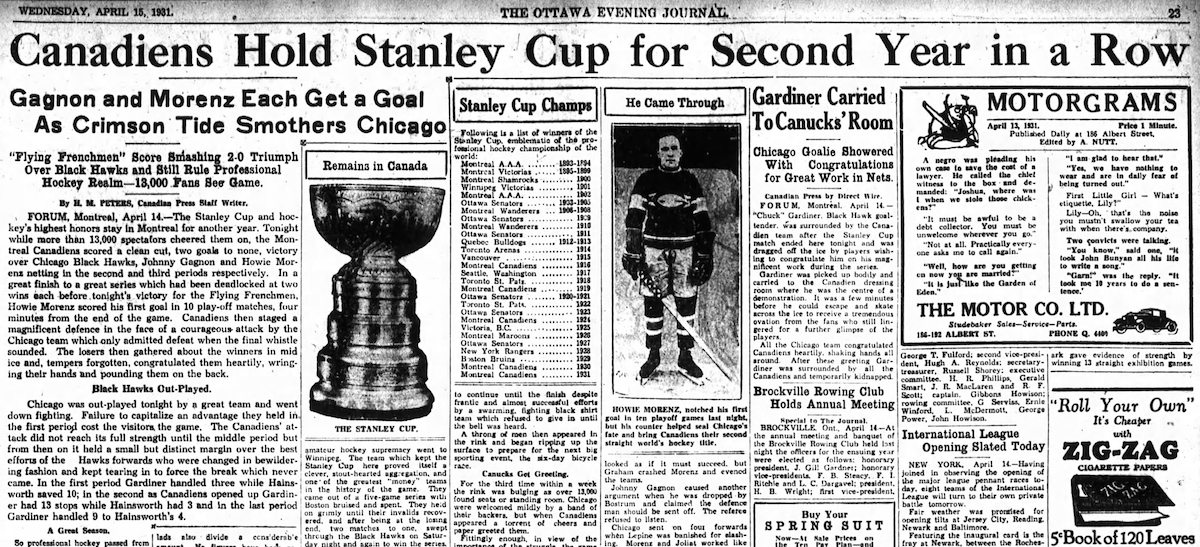

By the end of the 1930-31 hockey season (still seven months prior to the opening of Maple Leaf Gardens), Foster Hewitt was calling all the most important games on the radio from coast to coast. He called the Memorial Cup finals between the Elmwood Millionaires (Manitoba) and the Ottawa Primroses on March 23, 25 and 27; the Allan Cup games between the Winnipeg Hockey Club and the Hamilton Tigers on March 31 and April 2; and the last three games of the Stanley Cup Final on April 9, 11 and 14 as the Canadiens beat the Black Hawks in five games. (More on the finale of that series next week.)

Writing in the Toronto Star on April 15, 1931, Foster’s father had this to say:

“The hockey season which ended last night with a coast-to-coast network broadcast of the Stanley Cup final was another triumph for CFCA (Toronto Star). Over 50 hockey games were broadcast during the season by Foster Hewitt and these included all the Maple Leaf Hockey Club sheduled games, the finals for the OHA championships in all series, the Allan Cup finals at Winnipeg, the Memorial Cup finals at Toronto and Ottawa and the Stanley Cup finals at Montreal. Foster Hewitt’s voice is now as familiar in Vancouver and Halifax as it is in Toronto and throughout the province of Ontario.”

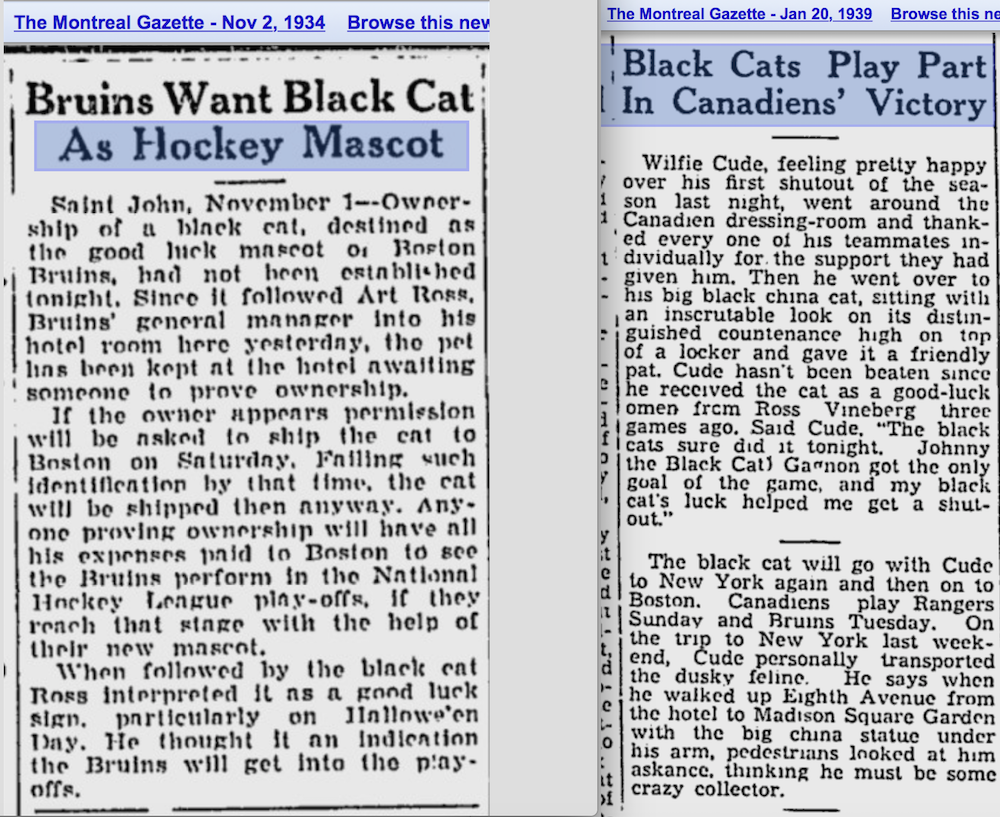

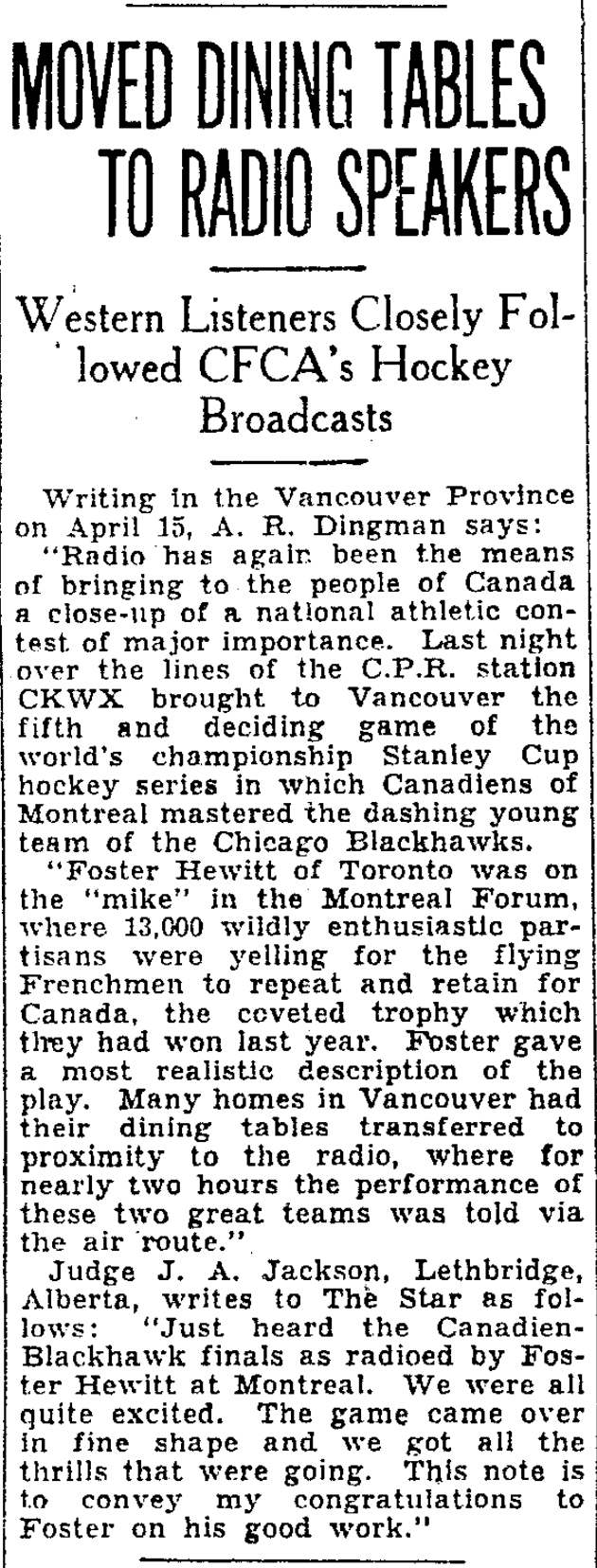

And to show that W.A. Hewitt wasn’t just being a boastful father, consider these stories in the Toronto Star of April 21, 1931, picked up from other Canadian cities: