Though celebrations pretty much started on New Year’s Day in 2017, the NHL will officially reach its 100th birthday late this fall. The league was formed in November of 1917 in a series of meetings that culminated on November 26. The first games in NHL history were played on December 19, 1917.

The NHL Official Guide & Record Book for the 2017-18 season began shipping from the printer’s yesterday. The Guide is not quite as old as the NHL, but it does have roots dating back to the 1932-33 season when Jim Hendy published his first Hockey Guide. As I said in a similar story two years ago, Hendy worked on his Guide until 1951, after which he turned over the book to the NHL. Through expansion after 1967 and right into the 1980s, the book maintained Hendy’s original “pocket” format, although as the NHL grew from six to 21 teams it was split into two books: a Guide and a Register. In 1984, Dan Diamond proposed a reorganization and redesign that saw the NHL Official Guide & Record Book remodelled into magazine-sized pages including photographs for the first time. Dan’s first Guide was 352 pages. This year’s is a record 680 pages!

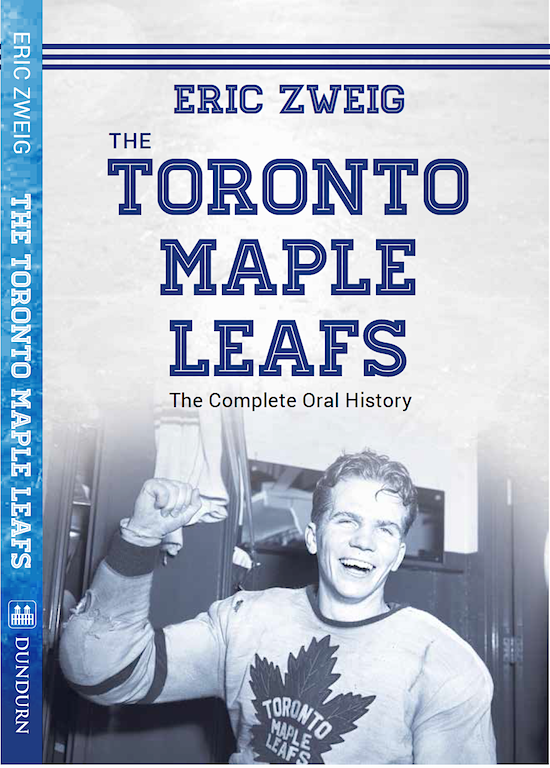

The National Bookstore cover.

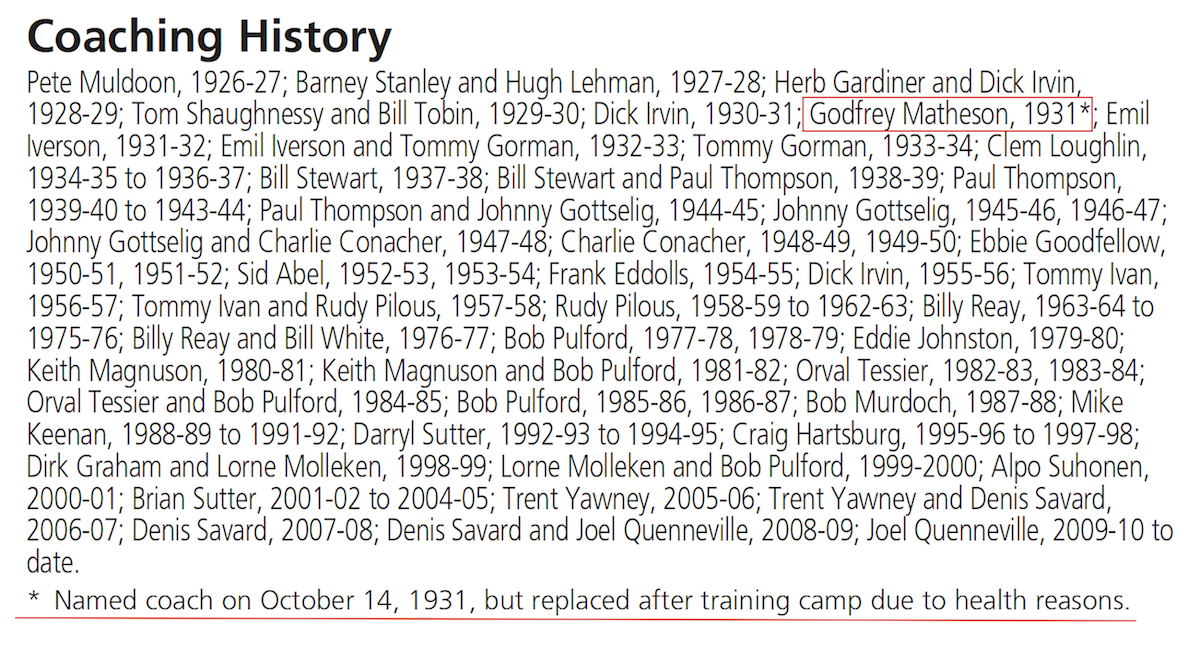

When I wrote two weeks ago about the changes necessitated by new information about Chicago Blackhawks coach Godfrey Matheson, one of the comments I received noted that it was nice to see that corrections can still be made based on events from 80+ years ago. The truth is, the NHL Official Guide & Record Book is ever-evolving. A few of the records we’ve updated since last season were among the oldest in the NHL.

The NHL Media cover.

Some NHL records may last forever. No one is likely to match the 2.20 goals-per-game (44 goals in 20 games played) that Joe Malone averaged in the first NHL season of 1917-18. Punch Broadbent’s record of scoring in 16 straight games in 1921-22 seems pretty safe too in this era of low-scoring hockey. Same with most of Wayne Gretzky’s records from the 1980s and ’90s. Even so, it’ll take some doing to match the 22 shutouts George Hainsworth posted in 1928-29 – especially considering that Hainsworth did it in a 44-game season! Tough to beat his 0.92 goals-against average too.

The New York Rangers custom cover.

Still, Auston Matthews’ four-goal game in his NHL debut in October of 2016 has found its way into the NHL Guide & Record Book for this season – although Matthews only holds down second spot for the most goals by a player in his first NHL game … behind Joe Malone and Harry Hyland, who scored five goals on the first night in NHL history. Adding Matthews also allowed us to correct a 100-year oversight by including the name of Reg Noble on the list of four-goals debuts. He also accomplished his feat on the first night in NHL history.

New Jersey Devils custom cover.

Corey Perry of the Anaheim Ducks matched a pretty long-ago feat during the playoffs this past spring. While not quite as dramatic as the three overtime goals scored by Mel Hill in a single series for the Boston Bruins against the New York Rangers (including a game seven series winner) in 1939, Perry did join Hill and Maurice Richard (who did it over two series in 1951) as the only players in NHL history to score three overtime goals in one playoff year. Perry got one in the first round versus Calgary, a second in the second round versus Edmonton, and his third in the Western Conference Finals against Nashville.

Calgary Flames custom cover.

As Dan Diamond writes in his introduction this year, the 2018 Guide & Record Book will also reflect a recent and welcome decision by the NHL to apply today’s standard to earlier years by identifying certain players who played the majority of the regular-season for teams that would go on to win the Stanley Cup. Previously, for various reasons, these players were not considered to be official Cup winners. This has changed. The following six players have now been added to their club’s list of Stanley Cup-winners: Vic Stasiuk (Detroit 1954), Jackie Leclair (Montreal 1957), Kent Douglas (Toronto 1964), John Brenneman (Toronto 1967) and Don Awrey and John Van Boxmeer (Montreal 1976).

The NHL Official Guide & Record Book will begin showing up in bookstores in September. If you’re a media person who receives The Guide from the NHL, or from Dan Diamond & Associates directly, you should be getting your copy soon. If you’re a customer who prefers to purchase it directly from our office, it’s time to send in your email order or click this link to the dda.nhl eBay site.