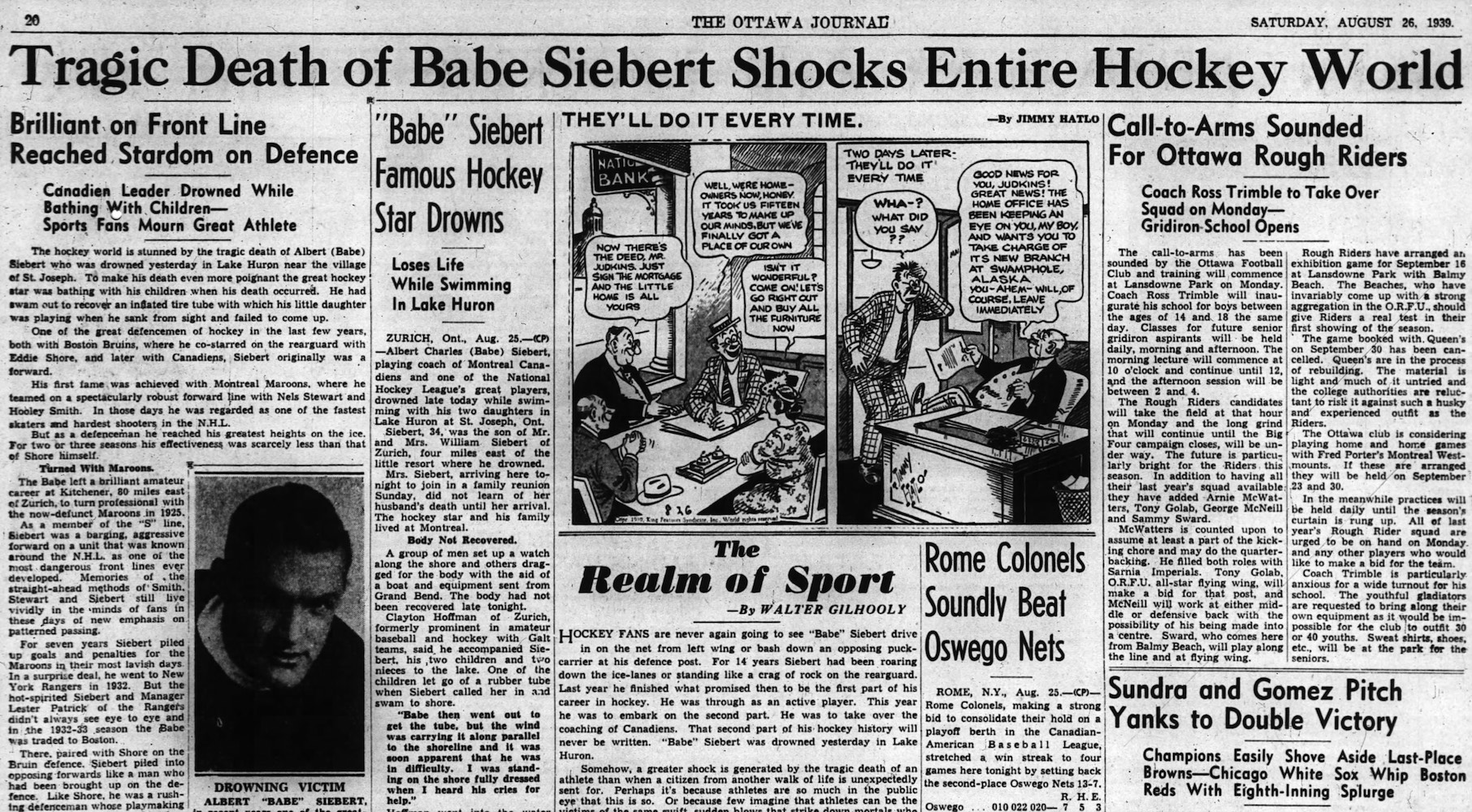

The death of former NHL goalie Ray Emery, who drowned in Lake Ontario at Hamilton this weekend at the age of 35, brought to mind the deaths of two other old-time hockey players. I’ve written before about the accident that killed hockey star Hod Stuart in the summer of 1907. Like Stuart, Babe Siebert left a young family behind when he also drowned at the age of 35. Siebert was swimming in Lake Huron near the town of St. Joseph, Ontario, on August 25, 1939.

Babe Siebert (whose given names are usually listed in hockey records as Albert Charles, but whose birth certificate and marriage documents record his name as Charles Albert) is not a well-known name today. He was a big star in the 1920s and ’30s and would later be elected to the Hockey Hall of Fame. But that was all a long time ago…

Briefly, Babe Siebert was a star forward with the Montreal Maroons from 1925 to 1932, helping the second-year team win the Stanley Cup in his rookie season of 1925–26. He later played right wing on The S-Line (or Triple-S Line) with fellow future Hall of Famers Nels Stewart and Hooley Smith. Though lacking the size of a modern power forward (Siebert was pretty big for his era at 5’10” and 182 pounds) he was as tough as he was talented. A game against the Maroons was usually a rough one.

Playing with Boston in 1933–34, Siebert was moved to defense by Art Ross when Eddie Shore was suspended following the Ace Bailey Incident. Siebert soon became an All-Star at his new position, but even so, the Bruins traded him to the Canadiens before the 1936-37 season. He won the Hart Trophy as NHL MVP that year.

“On the ice he’s a tough hombre,” wrote Harold Parrott of The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, on January 19, 1937, “and Lionel Conacher of the Maroons says, he can’t be trusted with a stick in his hands. Off the ice he’s as gentle as a lamb, caring for his crippled wife. At home games at the Forum the Babe is always first dressed after the battle, and he hurries to carry his wife to their automobile. He always installs her, long before game time, in a comfortable seat behind the goal that the Canadiens will defend in two of the three periods – so that she can watch his play more closely.”

According to Siebert’s biography on the Hockey Hall of Fame web site, his wife (Bernice) had been paralyzed from the waist down after complications during the birth of their second child.

“‘A tough guy,’ they called the Babe,” said a piece in the Montreal Gazette by Harold McNamara the day after Siebert died, “but they didn’t see him working around the house, an apron draped over his suit, doing work that his wife was unable to do. They didn’t see him playing with his two children, showing pictures of them around the dressing room.”

What makes Siebert’s death so tragic was that – having been named the Canadiens new head coach in June of 1939 – he was on a short vacation with his two girls, aged 10 and 11, at the time. He’d brought them to his parents home in Zurich, Ontario, towards the end of August a few days before an 80th birthday party for his father.

On the afternoon of August 25, 1939, Siebert, his two daughters, two nieces and a local friend, Clayton Hoffman, were enjoying a day at the beach. When it was time to go, and Siebert called in the children, one of them left an inflated inner tube floating in the lake. “Babe then went to get the tube,” Hoffman explained. “But the wind was carrying it along parallel to the shoreline and it was soon apparent he was in difficulty. I was standing on the shore fully dressed when I heard his cries for help.”

Hoffman went in after Siebert. He got within about 35 feet. “Before I could reach him, Babe had gone down for the last time.”

Efforts to recover Siebert’s body took three days. He was eventually found by his brother Frank and another local man in 150 feet of water about 40 feet from the spot where he’d disappeared. A funeral and burial took place in Kitchener, Ontario, on August 30.

“He was not only a fine man from a point of view of hockey but he was a model father and a fine husband to his sick wife,” NHL president Frank Calder had said upon learning of Siebert’s death. “He was a model of self-sacrifice. He was not the kind of player who made money in the winter and spent it in the summer. Siebert was a conscientious man who worked all year round. There is nothing too fine that can be said about him.”

A day before the funeral, the Montreal Canadiens announced that Art Ross had proposed a benefit game with the Bruins for before the season to raise money for Siebert’s family. It would expand into a game between the NHL All-Stars and the Canadiens played on October 29, 1939. The All-Stars scored a 5-2 victory in front of only 6,000 people. Still, it was said that the goal of raising $15,000 would be met.

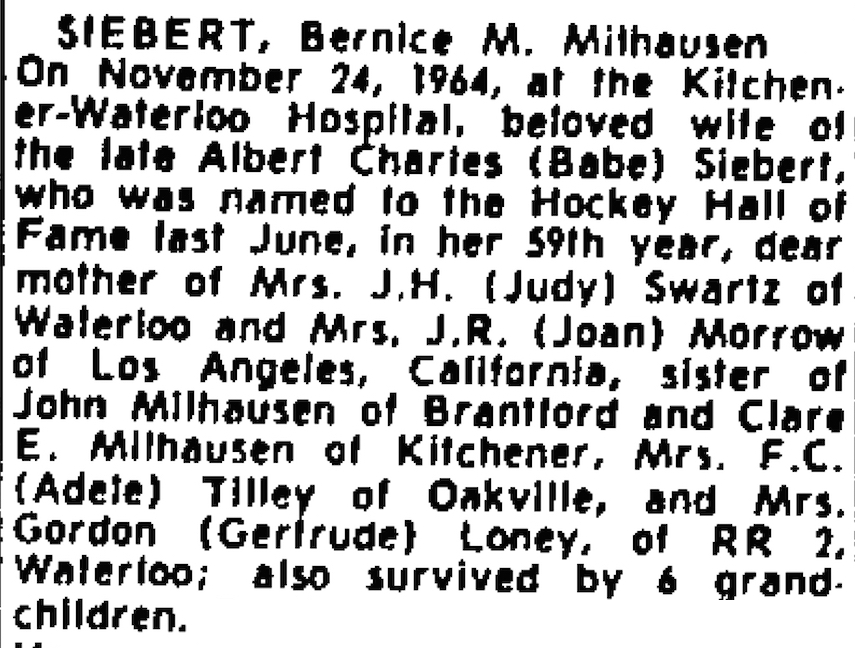

I haven’t been able to learn much about Bernice Siebert’s life after her husband’s death, but she did live to see the Babe voted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in June of 1964 and officially inducted that August. She passed away in Kitchener on November 24, 1964 at age 58. In addition to a brother and three sisters, she was survived by her two daughters and six grandchildren.