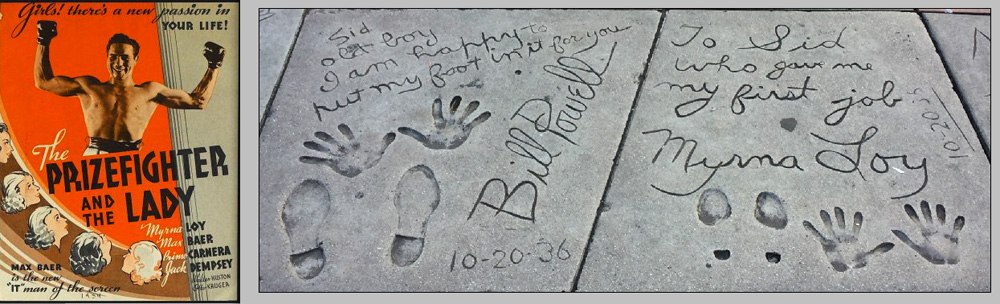

Last week, I caught some of The Prizefighter and the Lady on Turner Classic Movies. It stars Max Baer, who was a top heavyweight contender at the time, in his first movie role as the Prizefighter, and Myrna Loy as the Lady. It was made in 1933 and received an Academy Award nomination for Best Writing, Original Story. Generally speaking, it still gets good reviews. Admittedly, I didn’t see that much of it, but from what I did see, it seemed much more interesting now as a piece of history than it did as a movie.

I won’t go into the plot, but it builds towards a big fight scene at the end where Baer’s character (Steve Morgan) fights the real heavyweight champion of the time, Primo Carnera. (In real life, Baer would beat Carnera for the title a year later.) In the film, the fight is promoted and also refereed by Jack Dempsey playing himself, and before the bout begins Dempsey is joined in the ring by other legendary heavyweight champions of the past, Jess Willard and James J. “Jim” Jeffries. I recognized Jeffries right away from his strong resemblance to hockey legend Cyclone Taylor!

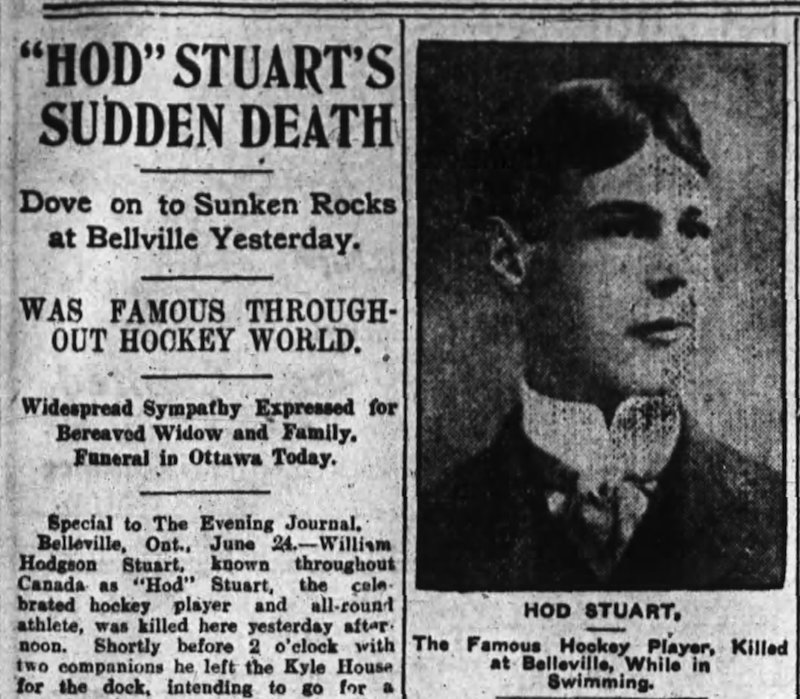

Movie poster plus the hand and footprints of William Powell and Myrna Loy at the

Chinese Theater in Hollywood. W.S. Van Dyke, who directed The Prizefighter and the Lady, would later direct Powell and Loy in the first of “The Thin Man” movies.

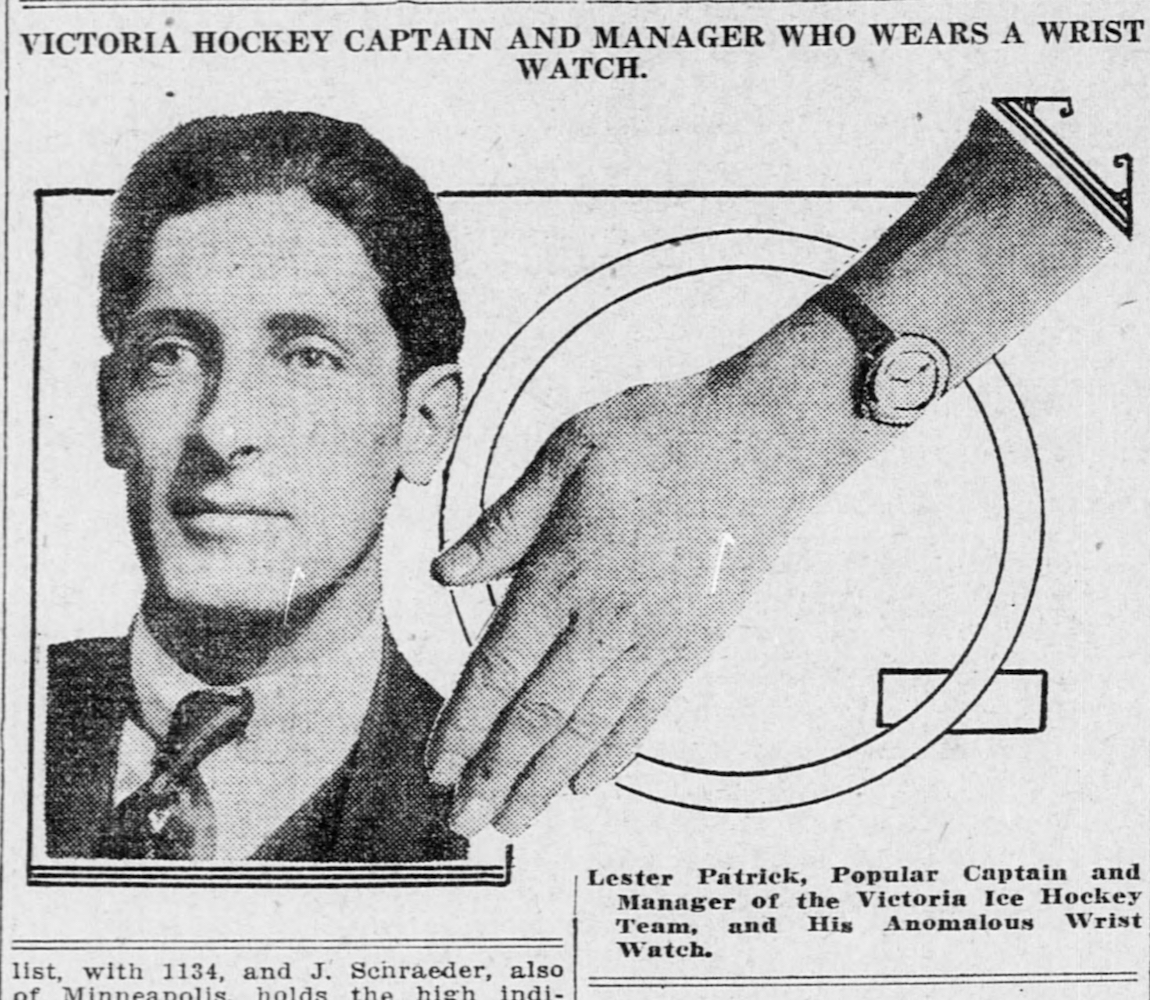

I first learned of Cyclone Taylor’s resemblance to Jim Jeffries in Eric Whitehead’s 1977 biography Cyclone Taylor: A Hockey Legend. (Reading that book, and then Whitehead’s biography of Frank and Lester Patrick, inspired me to write my first book, the historical fiction novel Hockey Night in the Dominion of Canada.) Whitehead writes of hockey fans in New York City taking to Taylor because of his skill and because of his resemblance to the former heavyweight champ. He says they called him “Little Jeff.”

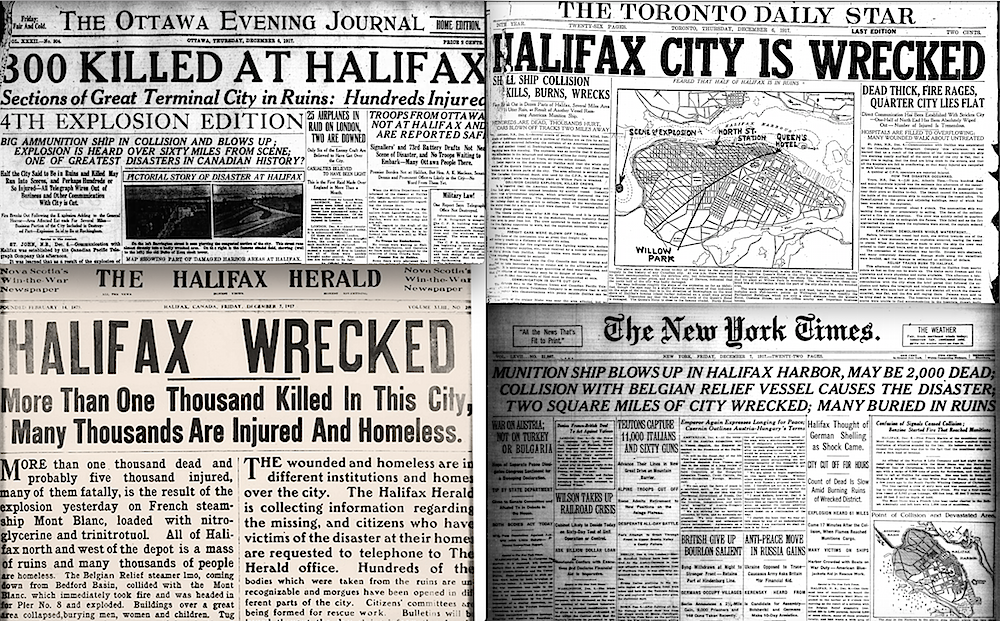

While I couldn’t find any newspaper references to that specifically, Jeffries was actually in New York at the same time as Taylor and the Ottawa Senators were there to face Art Ross and the Montreal Wanderers in a postseason series in March of 1909. Jeffries was very much in the news, with fight promoters offering him huge money for the time – $50,000 and up – to come out of retirement to fight Jack Johnson. (Jeffries would be the first “Great White Hope” to fight the controversial Black heavyweight champion when he lost to him on July 4, 1910.)

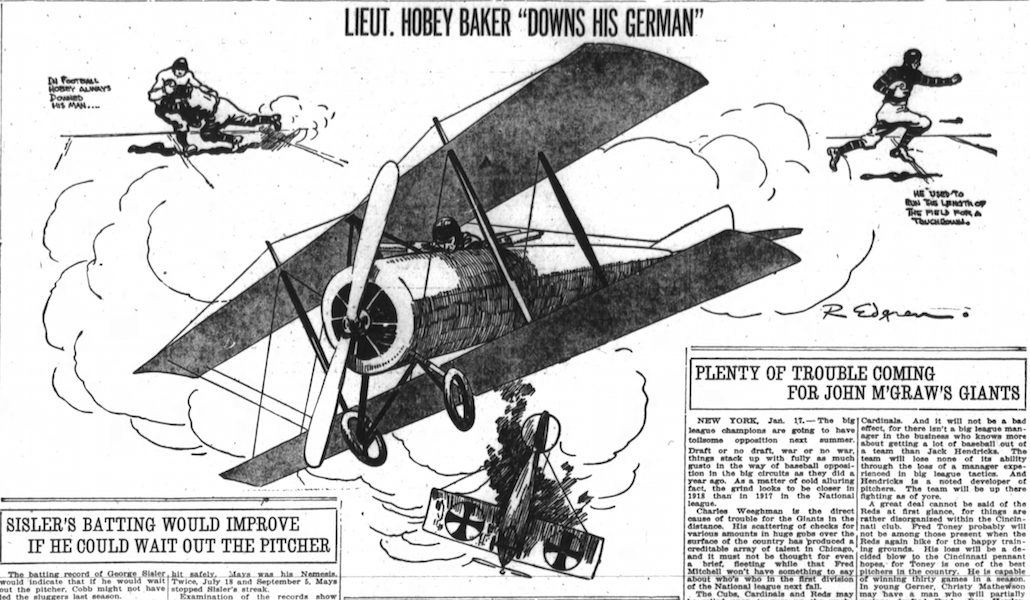

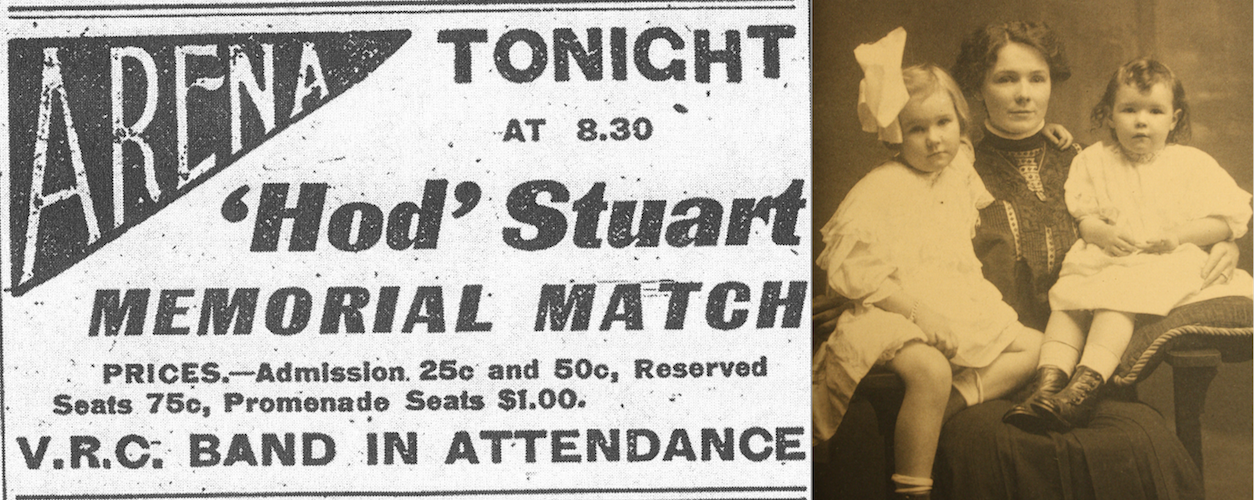

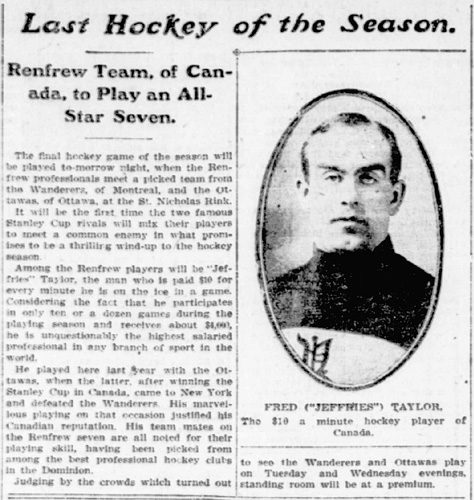

The clipping below doesn’t use the nickname “Little Jeff” but does come pretty close to confirming Whitehead’s account by referring to Cyclone as “Jeffries” Taylor…

Article in The New York Daily Tribune on March 18, 1910, when Taylor

Article in The New York Daily Tribune on March 18, 1910, when Taylor

returned to New York as a member of the Renfrew Millionaires.

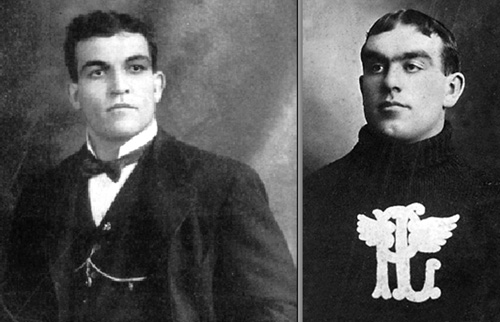

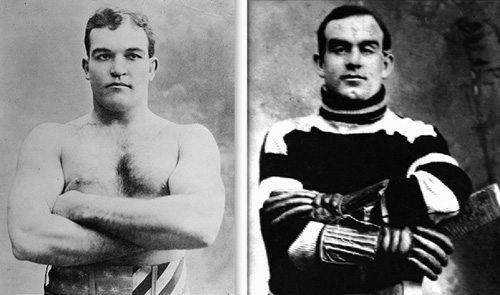

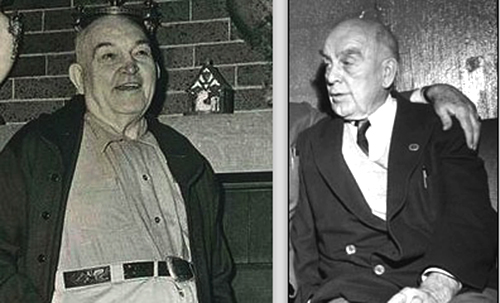

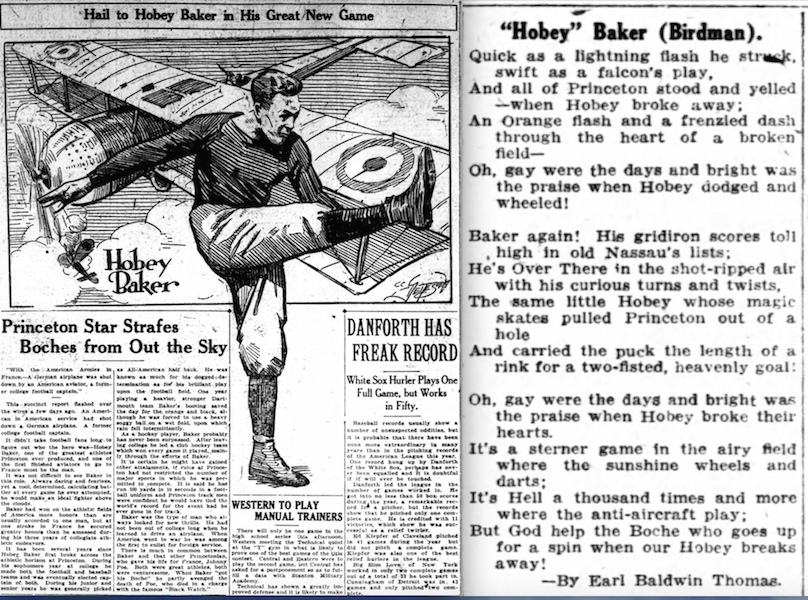

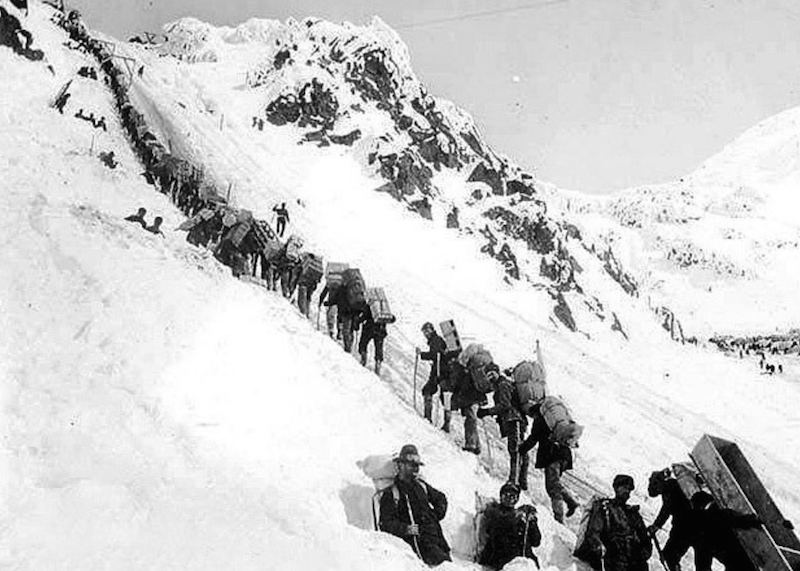

And while you wouldn’t exactly confuse one for the other (especially considering that Jeffries was about 6-foot-1 and 225 pounds in his prime while Taylor was 5-foot-8 and 165 pounds), there definitely is a resemblance…