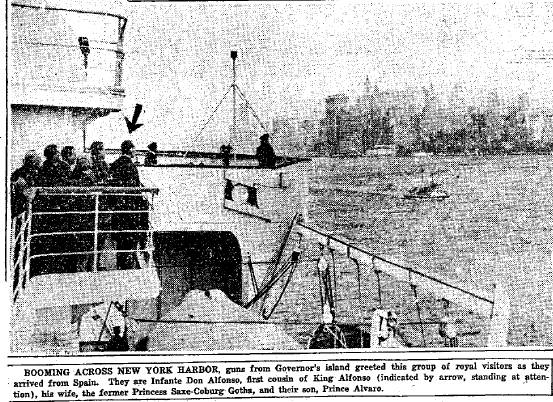

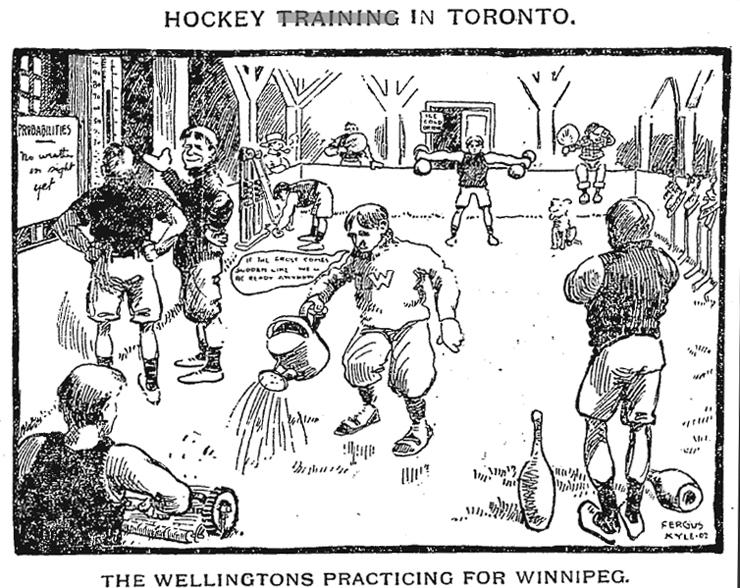

I hadn’t planned to write on this subject, but last week I came across the two old photographs shown below. (I already had the cartoons from years ago.) I found the pictures online in the March 1902 edition of The Canadian Magazine. I LOVE pictures like these, and the timing was perfect, so here we go…

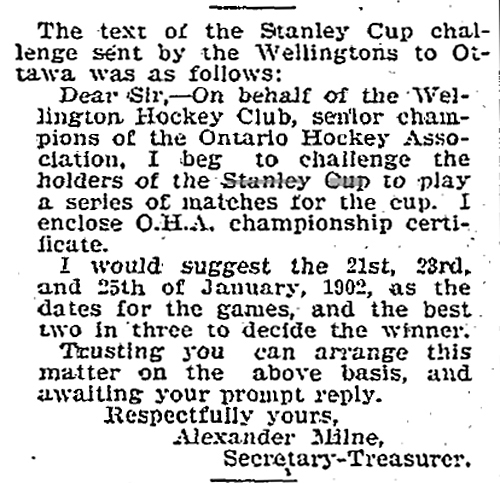

On this very day, way back in 1902, the first team from Toronto to play for the Stanley Cup opened a best-of-three series in Winnipeg. The Wellington Hockey Club of Toronto (known as the Wellingtons, and often called the Iron Dukes after the first Duke of Wellington for whom they were named) had been formed around 1895 as a juvenile team for youngsters in the Jarvis Street area of downtown Toronto. Soon, they entered the Junior division Ontario Hockey Association and in 1896-97 the Wellingtons won the provincial championship. Moving up to Intermediate, and then to Senior, the Wellingtons won the OHA Senior title in 1900 and 1901. (They would also win it in 1902 and 1903 before withdrawing from hockey suddenly and surprisingly just prior to the 1903-04 season.) As champions of 1900-01, they sent word to the Stanley Cup trustees in Ottawa saying they wished to challenge the Winnipeg Victorias for the prized trophy at the start of the 1901-02 season.

In this era, the Stanley Cup was a challenge trophy. Because of the need for natural ice, the hockey season only stretched from late December to mid March. Train travel meant leagues had to be fairly local, so in order to make the Stanley Cup available to teams all across Canada, the senior champions of any recognized provincial association were able to challenge the current Cup champion. Games could take place before the season, after the season, and even right in the middle of a season.

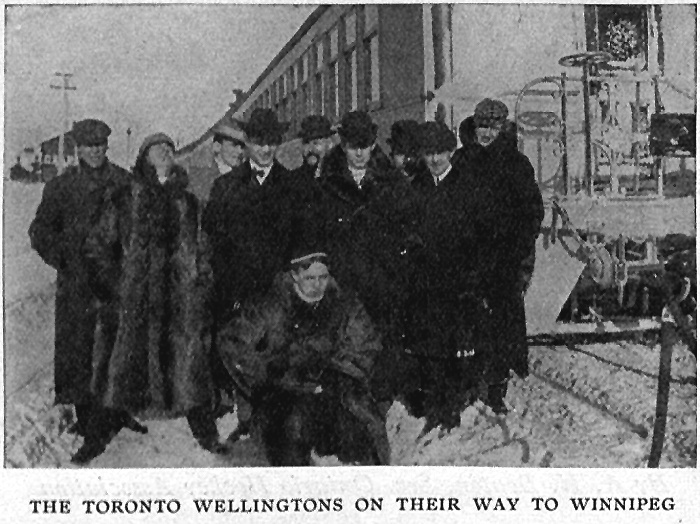

Hockey in Canada was considered strictly amateur at this time. The Ontario Hockey Association was the largest hockey league in the country and rigidly enforced the amateur code. The Wellingtons were fairly typical of Ontario hockey teams in that their players generally came from well-off families. Most of them worked in banks or for insurance companies. In fact, when the Winnipeg Victorias requested that the Stanley Cup series be played later in January, the Wellingtons objected because most of their players had to get back to Toronto in time to balance their books for the first of February!

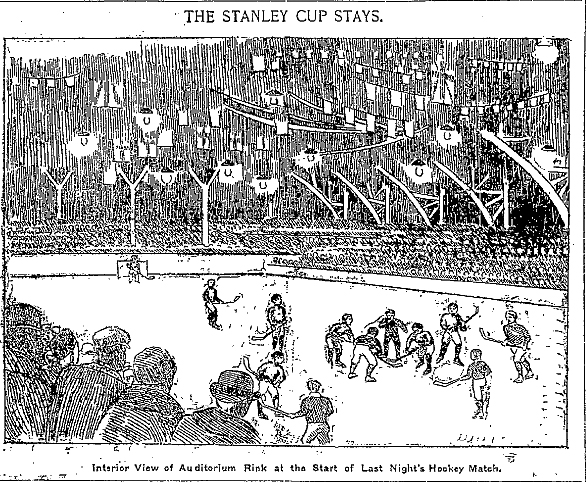

The Wellingtons were considered huge underdogs in their series with the Victorias. Outside of Ottawa (whose top team played in the Canadian Amateur Hockey League, which was considered a Quebec circuit), hockey in Ontario was not believed to be on a par with the game as it was played in Quebec and Manitoba. Many senior hockey players across the country were from the same types of background as the Wellingtons, but the OHA seemed much more determined than other leagues to maintain a gentlemanly style of play, which, sadly, didn’t help from a competitive standpoint. Compounding the problem in Toronto, the city had no first-class arena, with even the main rink on Mutual Street having an undersized ice surface and small seating capacity. Nor did Toronto have the same cold weather as Ottawa, Montreal, Quebec City or Winnipeg. In fact, during January of 1902, the weather in Toronto was unusually warm which hurt the Wellingtons’ ability to practice and hampered the quality of the few games they got in before leaving for Winnipeg on January 18.

Even so, the Wellingtons surprised most critics by keeping the games close and playing pretty good hockey against the Victorias. Still, they lost the January 21 game 5-3 and dropped the second game by the same score two nights later, giving the Winnipeg team a sweep of the series. “We played as hard as we ever played in our lives,” said Wellingtons captain George McKay, “but the checking … was much harder than we were accustomed to. It was fierce.” The Victorias were also said to be faster skaters.

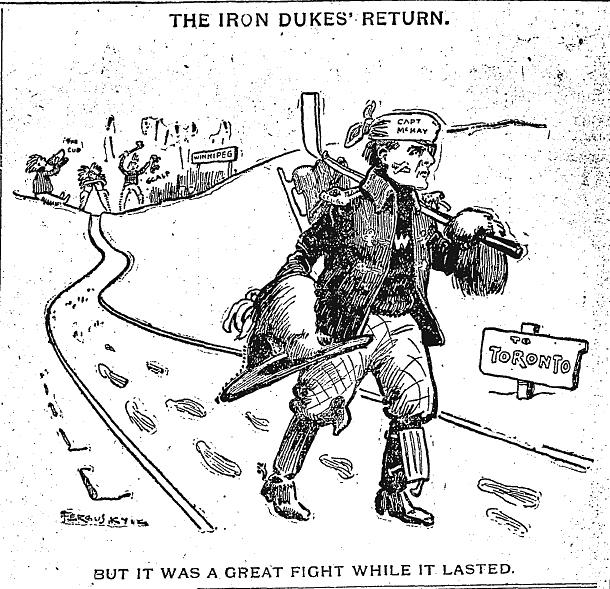

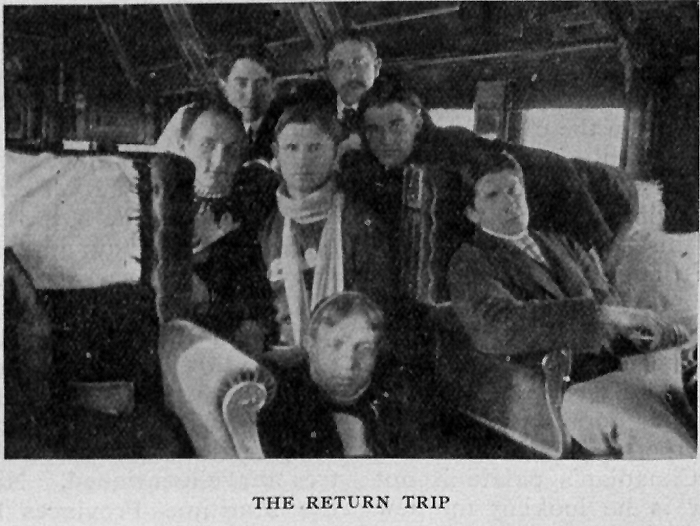

Despite the loss, Toronto hockey fans were proud of the team’s showing in Winnipeg. The Wellingtons arrived back in the city at 9 pm on January 28. Even though their train was seven hours behind schedule, there was still a big crowd to greet them at Union Station. “Captain McKay has his left arm in a sling,” according to the Toronto Star report. “Chummy Hill’s bad eye is cut again, Frank McLaren walks with difficulty, and George Chadwick is completely done up. Irvine Ardagh, Dutchy Morrison, Worts Smart and Jimmy Worts, are all in good shape.” The Wellingtons were taken from the train station to Shea’s Theater and were given a great reception.