It’s July 28. There’s plenty of other sports going on. The Olympics. Baseball. Football training camps. And the NBA draft is approaching. But even in the middle of summer, hockey manages to make headlines. There was the expansion draft a week ago, the regular NHL draft a few days later, and all the transactions around those. Now, free agency opens today.

Sure, COVID concerns pushed back these dates this year, but – in Canada, especially – it’s not uncommon to be talking hockey in summer time. It hasn’t been for a long time.

How long?

How about 118 years!

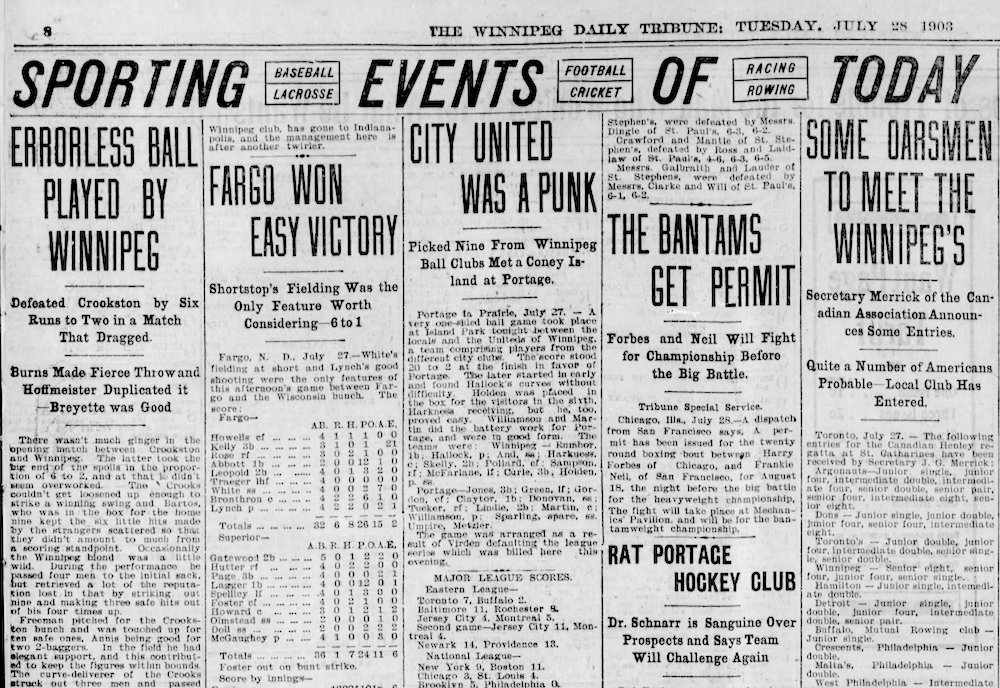

On July 28, 1903, (a Tuesday all those years ago), on a sports page in the Winnipeg Tribune filled with stories about baseball, boxing, tennis, soccer, and rowing, there was a small headline reading: RAT PORTAGE HOCKEY CLUB.

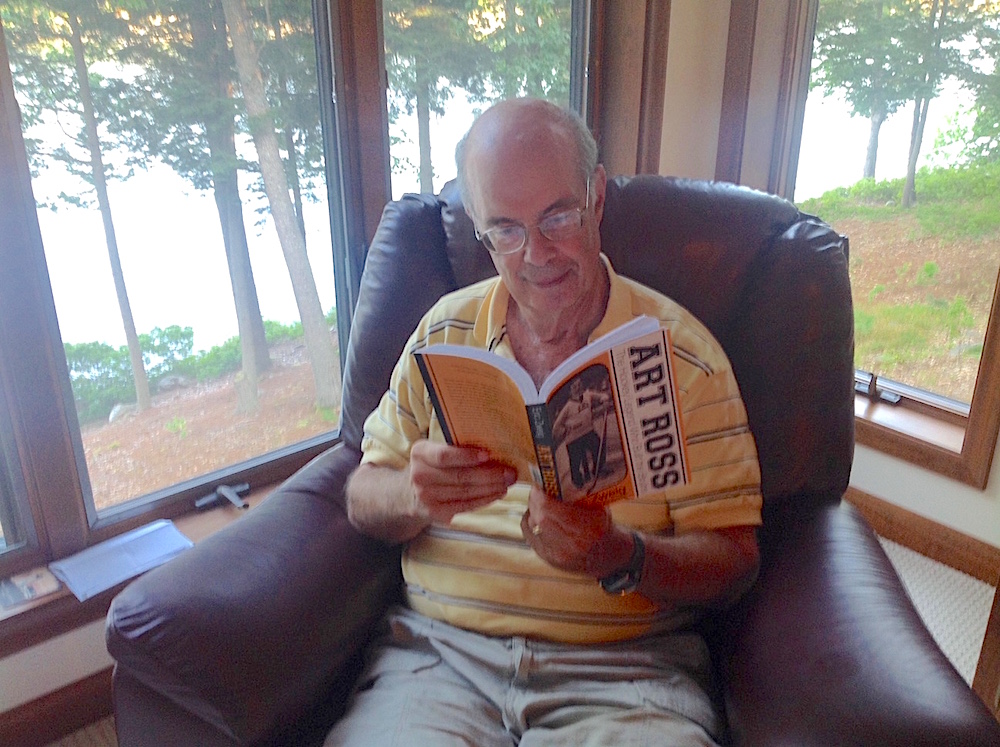

Rat Portage, for those who don’t know, is the original name of the northwestern Ontario town of Kenora. It came from a quick English translation of an Ojibwe phrase meaning “the Road to the Country of the Muskrat.” And the hockey club – the Thistles – (as some of you may remember), is the subject of a new book of mine — Engraved in History: Kenora Thistles and the Stanley Cup — that will be published in November. You’ll hear more about that, as well as a second new book for the fall (Hockey Hall of Fame: True Stories), in these pages in the coming months.

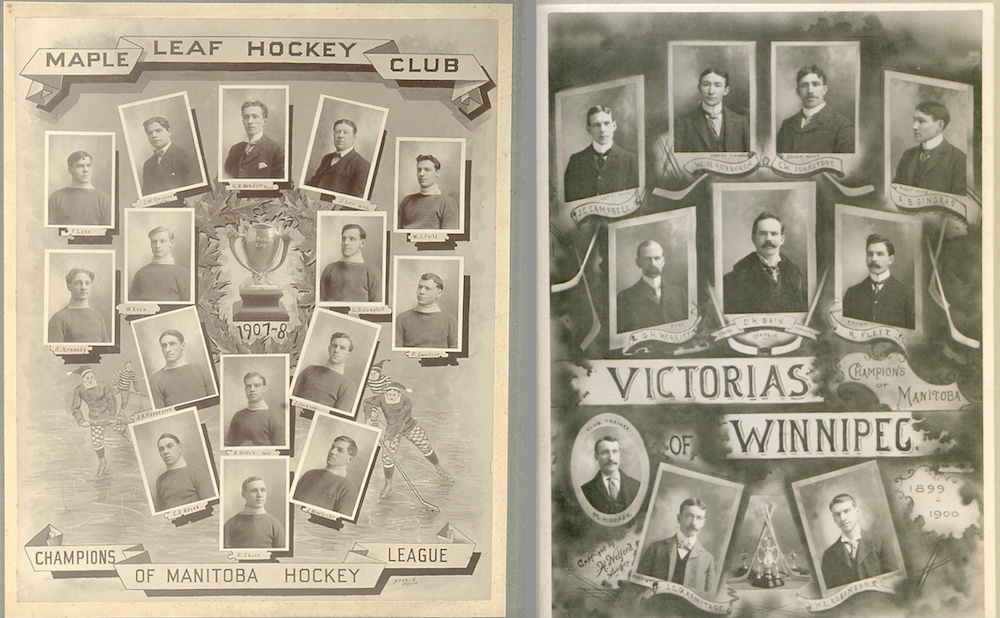

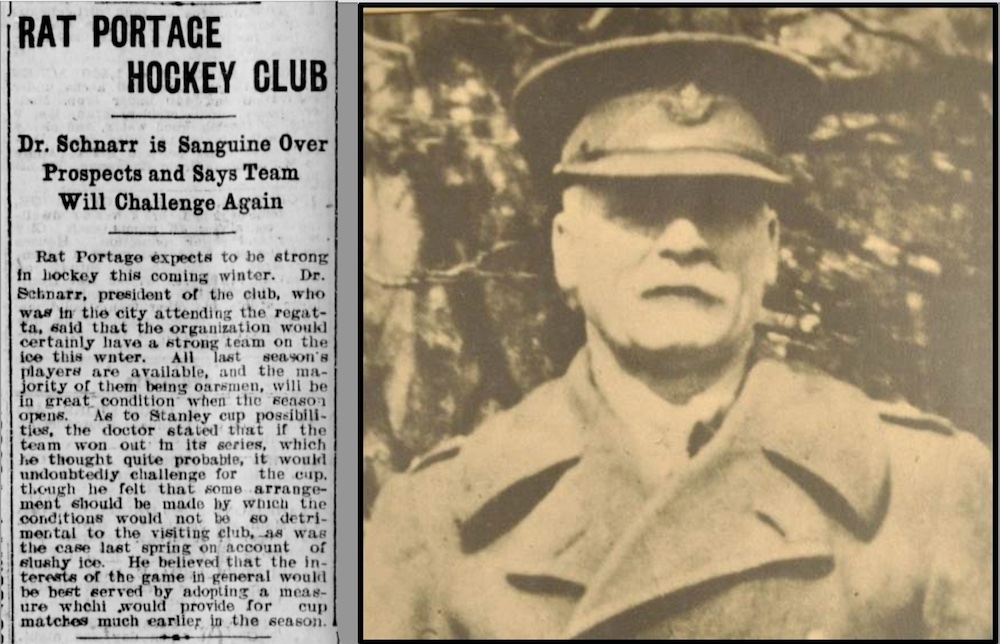

The Kenora Thistles would win the Stanley Cup in 1907, but the team dates back to the early 1890s, and first played for hockey’s top prize in March of 1903. That was four months before this article in the Tribune, which ran five months before the next hockey season would even start. But several Thistles hockey players were rowers in the summer, and some had recently been to Winnipeg for that city’s annual regatta. A Tribune reporter took the time to talk with Nelson Schnarr (a Rat Portage dentist and president of the Thistles hockey team who had attended the regatta) about his thoughts on his team’s chances of repeating as champions of the Manitoba and Northwest Hockey Association. Schnarr spoke of his high hopes; hence the sub-headline noting that he was “Sanguine” (optimistic, or bullish) “Over Prospects.”

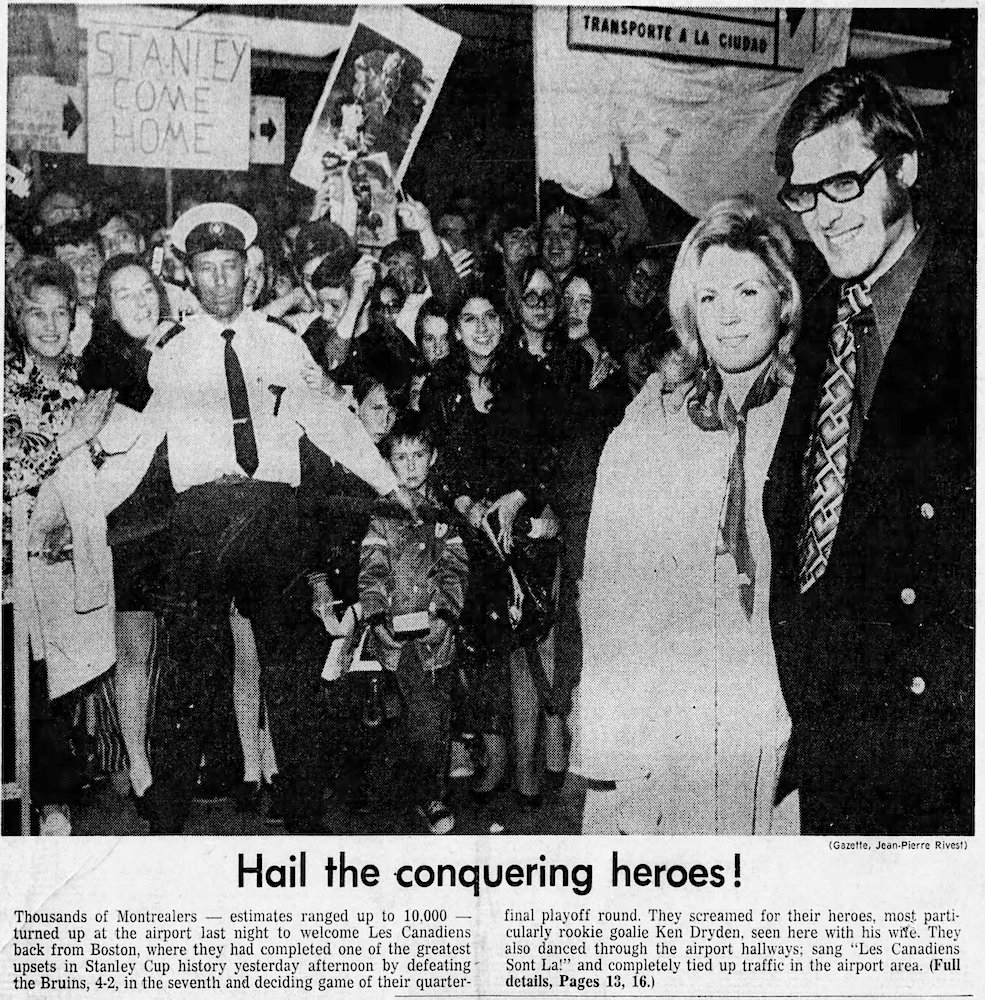

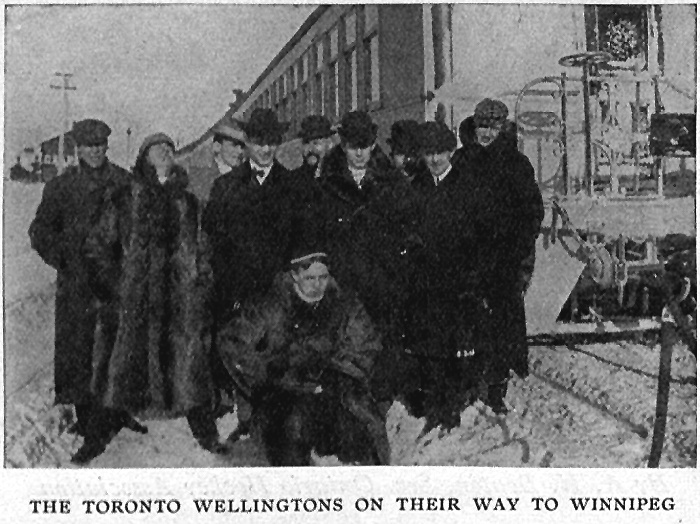

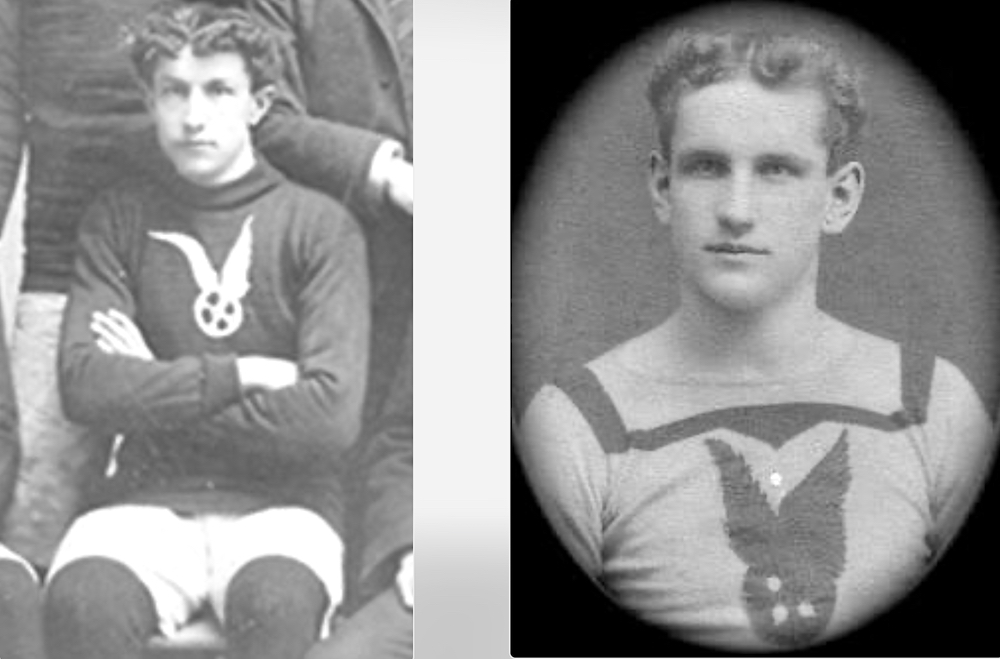

Future Hockey Hall of Famers Tommy Phillips (first from the left) and Si Griffis (second) played for the Thistles in winter and were with the Rat Portage Rowing Club in summer. They are joined here by Bob Rose (a goalie) and Norman MacDonald.

I came across the Tribune story about a year ago when I was in the early stages of writing the first draft. I delivered the revised manuscript two weeks ago. What follows is an excerpt from the introduction to the book:

If you know the story of the Stanley Cup champion Kenora Thistles you probably know it as one of the greatest underdog stories in Canadian sports.

And it is.

Sort of.

In January of 1907, the Thistles, from a town of approximately 6,000 people, travelled to Canada’s largest city, with a population of close to half-a-million (the entire country had only about 6.5 million people then), and defeated the defending champion Montreal Wanderers right there on their home ice.

But it wasn’t as if a semi-pro baseball team from Pierre, South Dakota, suddenly showed up in New York City and beat the Yankees in the World Series. No. The Kenora Thistles, in their heyday, were known right across North America as a hockey powerhouse. Yes, they were the smallest of small-market teams, even in 1907, but they reached their great success mainly with a group of home-grown superstars that was supported by their entire community.

during World War I. According to the Kenora Great War Project web site,

Schnarr had been a member of a local militia since 1896.

In many ways, the Kenora Thistles were like another small-market team of more recent vintage: the Wayne Gretzky-era Edmonton Oilers of the 1980s. Although Kenora was much smaller than Edmonton was, there are a great many similarities. Like the Oilers, the Thistles were a supremely talented team with a roster full of future Hall of Famers. They played an up-tempo, offensive game that may have put off traditionalists even in their day, but delighted most fans and impressed their rivals. But for both teams, success soon made it impossible to afford to keep their best players.

For much of Kenora’s Stanley Cup climb, hockey was still an amateur sport, so there wasn’t an issue with salaries. Still, the competition for players could be fierce. And then, the 1906–07 season marked the first year that Canadian hockey teams were openly allowed to pay their players. Contracts in this era were for no more than $2,000 which is certainly a far cry from the multi-million dollars of today, but the payroll very quickly became too much.

It wasn’t just the salary structure that made hockey in the early 20th so much different from the game we know today. The players were smaller and lighter, and they played much shorter seasons on natural ice that could melt into slush in warm weather. There was little protective equipment, yet the game was plenty rough.

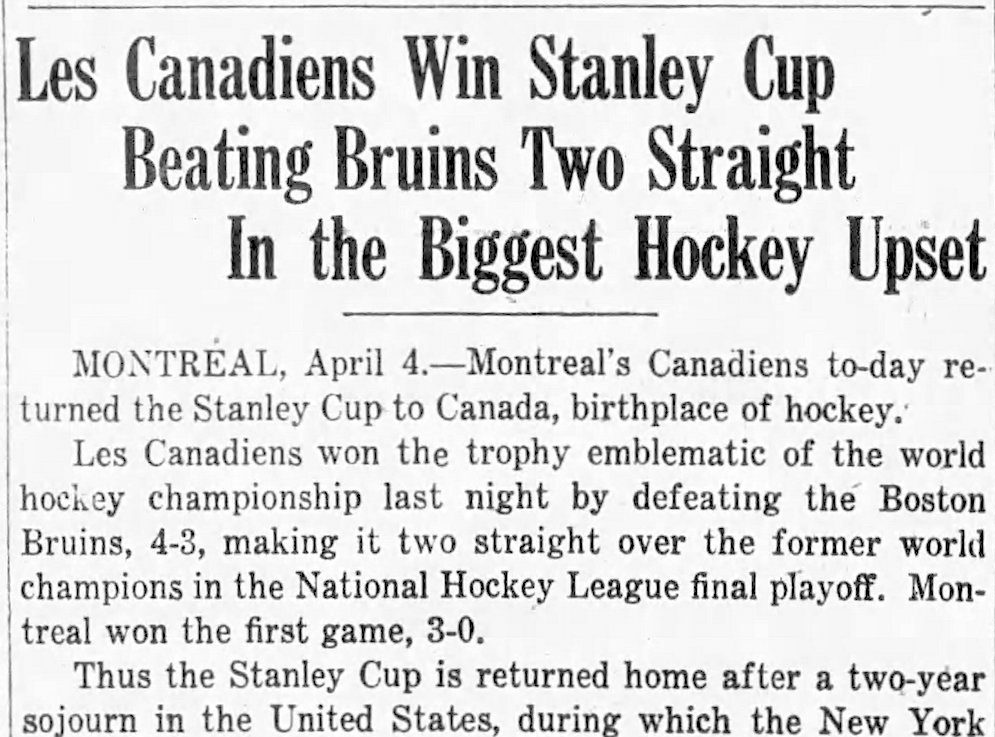

Roxy Beaudro and Tom Hooper rowed in Winnipeg during the summer of 1903.

Along with the addition of a rover, the other positions we know today still existed in the early days of hockey, but defensemen were called “point” and “cover point.” Rules and customs were different too. Without forward passing, skating and stickhandling were the main ways to advance the puck. Goalies had to remain standing at all times. And despite the extra man in the lineup, rosters were small. The seven starters were expected to play the entire 60 minutes, with substitutions generally made only in cases of severe injury. Obviously, the game would appear much slower to fans today, but to those in the stands back then, hockey was already considered the fastest and most exciting game there was.

Hockey fans circa 1907 didn’t have dedicated cable TV channels. They didn’t have 24-hour talk radio, twitter accounts, or apps for their smartphones to keep them up-to-the-minute with their favourite players and teams. They did have a lot of newspapers to read, and although there was usually only a page or two of sports news, the amount of hockey coverage was staggering. The hockey season lasted only the three calendar months of winter from late December until late March, but the gossip already ran all year long! It’s amazing how many rumours hockey fans could read about, and how much in-fighting and back-stage drama was going on between the teams, the leagues, and the players.

If you read the book – and I hope you will! – I think you’ll see that, the more some things change, the more they stay the same.