Congratulations to the 2014 World Series champion San Francisco Giants, and to MVP Madison Bumgarner. He was pretty amazing! Historically speaking, three championships in five years is quite an accomplishment … but somehow, the Giants just don’t feel like a dynasty to me. It’s not like there’s been that overwhelming feeling going into any season that there’s just no way to beat them. To me, that’s as much a part of being a dynasty as the winning.

This was the last World Series to be overseen by baseball commissioner Bud Selig. People seem to be well past saying that his legacy will be the canceled World Series of 1994, and are instead praising his developments of interleague play, the expanded playoffs with first one and now two wild card teams in each league, and the huge expansion of revenue those two ideas helped to create. But even though I truly do believe you might see something you’ve never seen before any time you watch a baseball game, it really seems that there are very few ideas in sports that someone hasn’t thought of before! Many of Bud Selig’s innovations for baseball – and even his ill-fated plans for contraction – were all advanced back in 1935 … by Hockey Hall of Famer Lester Patrick.

Lester Patrick was a big baseball fan, and a pretty good ballplayer in his younger days.

A couple of years ago, I wrote a story for The Hockey News making the case that the World Series of 1912 inspired Patrick to push for hockey to change the Stanley Cup playoffs away from the one-, two-, or three-game challenge series the Stanley Cup trustees had always favored toward the best-of-seven format used in baseball.

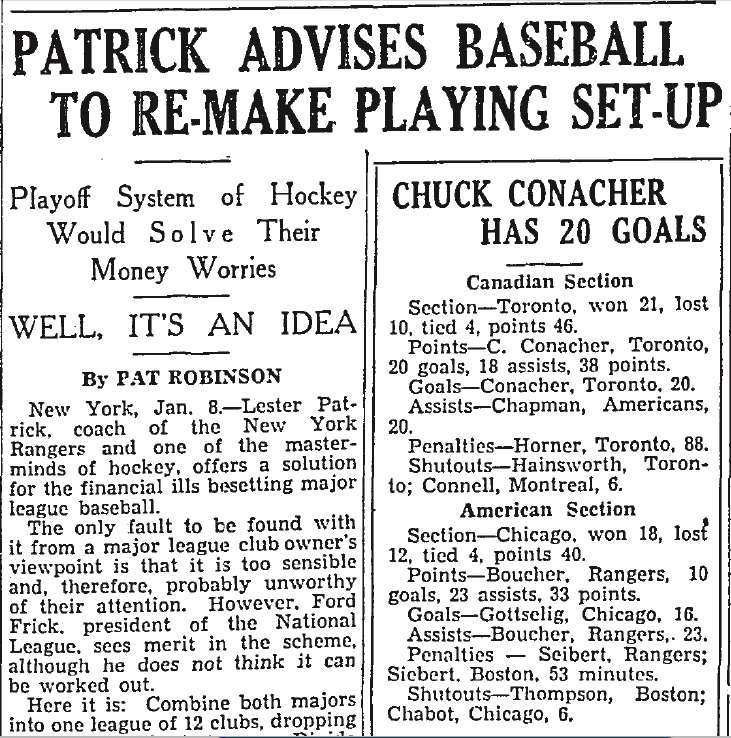

By 1934, Major League Baseball was a money-losing proposition in many cities because of The Great Depression, but Patrick had a few ideas to fix that. His plan, reported in newspapers in January of 1935, was to take the eight-team American League and eight-team National league and combine them into one 12-team circuit with two divisions of six teams each. They would play an interlocking schedule, and then – instead of only the pennant winners advancing directly into the World Series, as baseball had always done – the top three teams in each division would qualify for the playoffs. In the NHL, finances weren’t exactly booming at this time either, and American sportswriters loved to mock the league’s playoffs for being needlessly complicated and giving less worthy teams a chance to win. Still, Patrick said:

“If we had two major hockey leagues we’d lose money like the baseball people do. Our race would be over right now and we wouldn’t draw files playing out the schedule. Instead, interest is sustained for the playoffs, the crowds keep coming, and we make money. And we play to standing room only in the playoffs. But in baseball all too often one or two teams have the race sewed up long before the season is over and attendance fades to nothing. Under my plan, interest would be sustained throughout the year.”

As for interleague play:

“Imagine how towns like Pittsburgh and Brooklyn would turn out to see Babe Ruth, Jimmy Foxx and other stars playing the Pirates or Dodgers. Or how Washington and Cleveland would go for Dizzy Dean and other stars they never see. You may think Babe Ruth has been over exploited but, really, the baseball people have been dumb. They haven’t exploited him half enough. Think of the millions they could have made with him under a set-up as I have outlined.”

National League president (and future Major League commissioner) Ford Frick saw merit in Patrick’s plan but wasn’t sure how it could be carried out … particularly the contraction part. “Granting that it would work out well in baseball,” Frick said, “what towns could be dropped? No town would want to be deprived of its baseball.”

To Patrick, the answer was obvious. “Drop the four weakest towns financially.” His plan was to cut the St. Louis Browns, the Boston Braves, and the Philadelphia Phillies, all of whom already had other teams in the same cities (the Cardinals, Red Sox, and the Philadelphia Athletics) who were doing much better. The fourth team Patrick planned to drop was the Reds. “Only Cincinnati would be deprived of a major league club and judging by the box office receipts, that isn’t a major league town anyway.”

In the long run, Lester Patrick and Bud Selig were probably wrong about contraction, but the rest of Patrick’s plan looks an awful lot like the makeup of baseball Selig has given us today … although without the drug testing and instant replays!