Monday, March 2nd at 3 pm Eastern marks the NHL trade deadline. Everyone seems to be in agreement that the Toronto Maple Leafs are now fully committed to rebuilding around youth, although the general consensus is that they’ll be better off waiting until this summer if they plan to trade players such as Phil Kessel or Dion Phaneuf. We shall see…

Everyone also seems to be in agreement that this is the first time the Maple Leafs have fully committed to a youth movement. That’s not entirely accurate. Though this does appear to be the beginning of the first true rebuild since the introduction of the NHL Entry Draft (originally the Amateur Draft) in 1963, it’s certainly not the first one in team history.

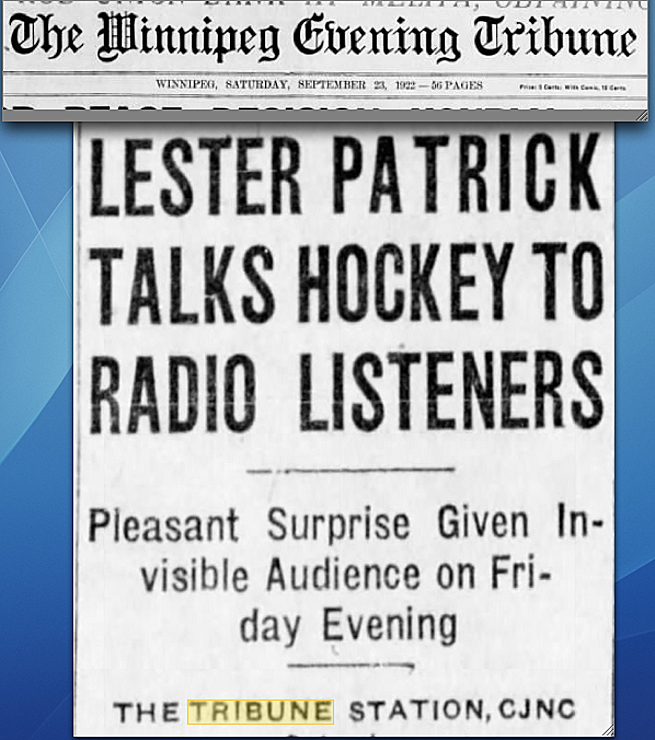

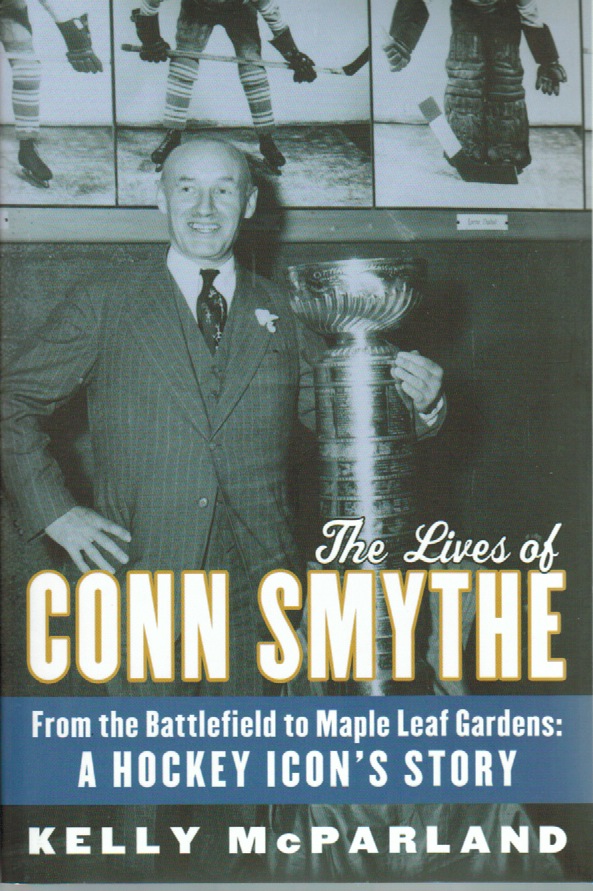

After giving up day-to-day control of the Maple Leafs while serving in the Canadian army during World War II, Conn Smythe resumed full charge of the team for the 1946–47 season. Toronto had won the Stanley Cup in 1945 only to fall out of the playoffs the following season, so Smythe and coach Hap Day decided a complete overhaul was necessary. Seven of 21 Leafs players from 1945-46 were traded, released or encouraged to retire. Another four were sent to the minors. The team would go with youth, and though Smythe couldn’t guarantee success, he promised that no team in the NHL would work harder than the new crew he assembled.

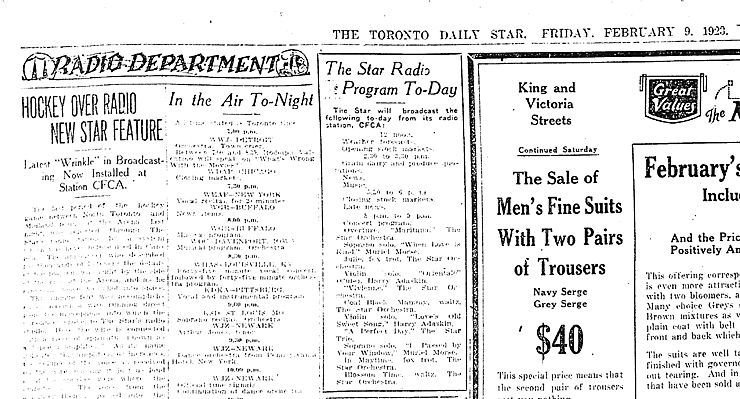

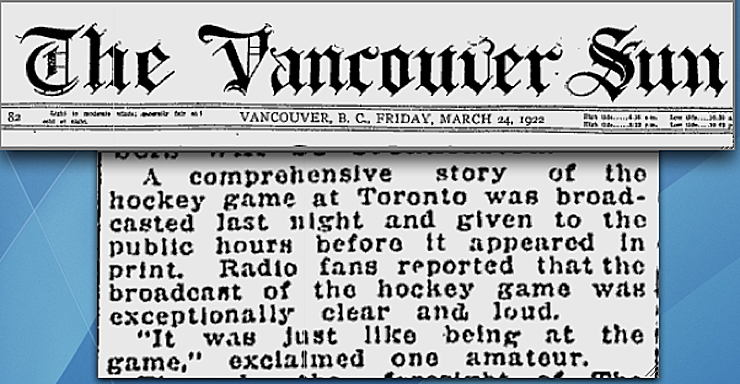

Unlike today, how to find and properly develop this new young talent wasn’t much of a concern for Conn Smythe. With no draft and only six NHL teams, it was easy enough for him to rebuild around youth because of the sponsorship of junior and minor league teams that allowed NHL clubs – particularly the wealthier ones; Toronto, Montreal and Detroit – to stockpile young players. (Boston tried the same thing after World War II, but Art Ross didn’t have the financial resources that Smythe did.)

Conn Smythe admitted that he was critical of the 1945–46 version of the Maple Leafs not because they’d missed the playoffs a year after winning the Stanley Cup, but because they had the fewest penalty minutes in the NHL. He vowed that would never happen again under his watch. In his 1980 autobiography, Smythe wrote that he couldn’t remember when he first uttered his famous motto, “If you can’t beat ’em in the alley, you can’t beat ’em on the ice.” He also wrote that his motto was often misunderstood, stating that he didn’t want his players to be bullies, he simply wanted them to refuse to be bullied. Still, while no newspapers appear to quote him using the “alley” expression during the rebuild in 1946, it became pretty obvious that Smythe wanted tough guys in his youth movement.

Smythe “told his players he wanted a fighting team filled with the desire to mix it with anyone,” wrote Jim Vipond in the Globe and Mail on September 27, 1946 as training camp got under way. “He further stressed the importance of team spirit and co-operation.” Gordon Walker of the Toronto Star wrote that same day of Smythe’s “brief, forceful address on club policy,” quoting Smythe directly: “If they start shoving you around, I expect you to shove them right back, harder. If one of our players should get injured by illegal tactics of the enemy, I expect the players on our team to see that the man responsible doesn’t get away with it.”

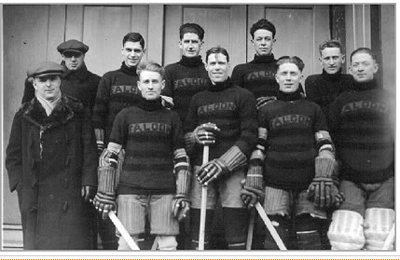

To reshape his team in the image he wanted, Smythe turned to the young players he already had in his farm system, which had been built by Frank Selke, who was now in Montreal after falling out with his longtime boss. Smythe reasoned that if the Leafs had to lose he’d rather lose with youngsters than with veterans and so on September 20, 1946, a week before training camp opened in St. Catharines, Ontario, the Leafs held what would now be called a “prospects camp.” The best from that group were invited to the main camp and were there when Smythe delivered his forceful address.

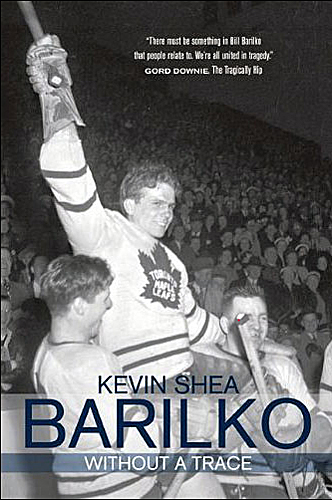

From that prospects camp emerged Bill Barilko (though he would begin the season in the minors), Gus Mortson and Howie Meeker, who would all be a part of four Stanley Cup–winning teams in Toronto over the next five years. Jimmy Thomson’s brief appearance with the Maple Leafs in 1945–46 had already earned him a spot at the main camp, where he too made the team and won four titles in the next five years. Three-time Cup-winners Garth Boesch and Vic Lynn also came out of the prospects camp, as did Tod Sloan although he needed a few more years to develop into the star he would become in 1950–51. Sid Smith hadn’t been there, but did make a brief debut in the NHL in 1946–47 before breaking out as a star a few years later. (There was, in fact, so much young talent in Toronto that Smythe would deal five players to Chicago the following season to land veteran Max Bentley.)

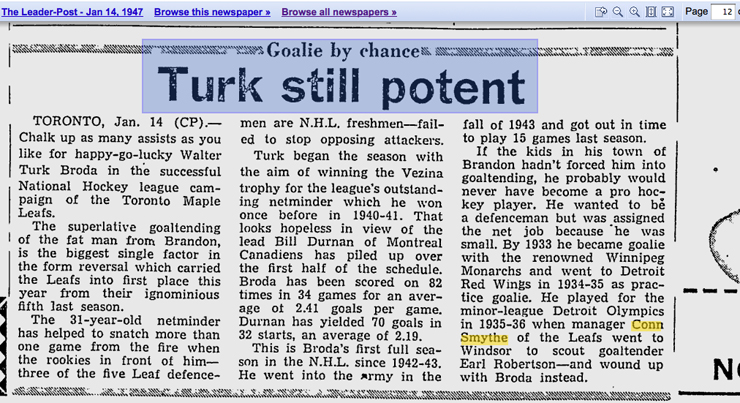

Smythe was confident entering the 1946-47 season that he’d put together a team he might win with a year or two down the road. Having Syl Apps and Turk Broda back in pre-War form, and with twenty-one year old Teeder Kennedy already entering his fourth season, certainly helped, but with six rookies among 12 new faces on the 18-man roster, Smythe down-played his expectations. “The Maple Leafs will suffer plenty of defeats this season,” he admitted. But he couldn’t completely hide his optimism: “We’ll win plenty, too!”

With a team that refused to back down from anyone, the Maple Leafs finished a surprising second behind the Canadiens in the regular-season standings. Frank Selke was critical of Toronto’s style all season, and early in the year he accused Maple Leafs defensemen of using “wrestling tactics.” There was plenty of rough stuff when the two teams met in the Stanley Cup Finals … which Toronto won to launch the club’s first dynasty.

It’s unlikely the rebuild will go quite as quickly this time!