Back in March, I wrote about Frank Patrick trying to come up with a glowing puck for better visibility … back in 1941. The other day, I came across this, which appeared in Sports Editor Frederick Wilson’s column in Toronto’s Globe newspaper on February 17, 1927:

Interesting that Wilson lumps this in with “other trick ideas” such as seven-foot nets and five-man teams, which I also wrote about back in March. I’m not going to go into to bigger nets again, but just consider this…

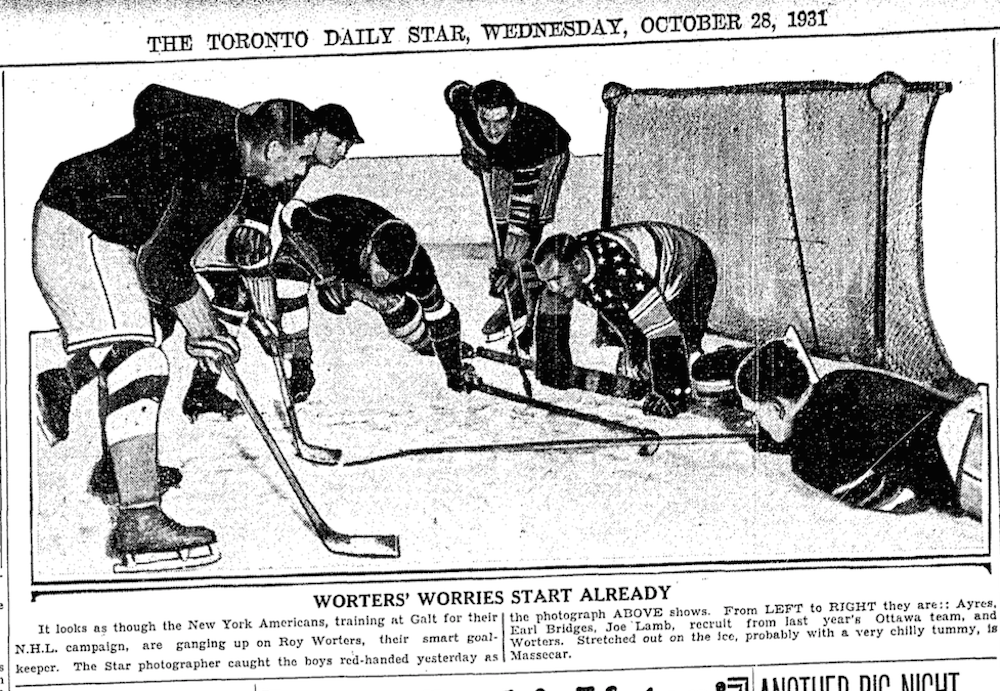

Space available around 5’3” Roy Worters, the smallest goalie in NHL history:

Space available around 6’7” Ben Bishop, the tallest goalie in NHL history:

Regardless of who’s in the Hockey Hall of Fame, which one looks easier to score on?!?

But let’s get back to pucks for a moment. Art Ross III shared this story with me during the writing of Art Ross: The Hockey Legend Who Built the Bruins. Among his many contributions to the game, Art Ross is famous for designing (refining, really) the modern hockey puck. But his son, the second Art Ross and father of Art III, figured he had a way to make it even better. This would likely be some time during the late 1950s. It didn’t work out.

Dad got the idea for a new puck, one with more color and, therefore, “followability.” Spaced at equal intervals around the outer inter edge of the black puck were orange inserts. The color matched the label on the puck. I seem to recall that the first trial version had triangular wedges – think pie slices – but the final product had something on the order of a hollowed out cylinder: a round disk on the top and bottom, same beveled edges, but the disks would be connected by a thin strip of black rubber which was counter-sunk into the edge rubber. It’s a bit hard to describe, but the point was that there were six orange implants on the outer edge of the puck giving it enhanced visibility and a cool look if you spun it slowly. Dad, ever creative and thoughtful, decided to call his innovation an “Art Ross Puck.” You didn’t need a focus group for that one.

We lived in [the Boston suburb of] Newton at the time on the Charles River, a good part of which froze each winter. My sisters and I were the OPTs – Official Puck Testers – and Dad joined us a couple of times. It was great fun zipping around whacking the disc with vigor and, best of all, we had almost an unlimited supply of pucks! It wasn’t very long, however – like two days, maybe – before the OPTs noticed a problem. On a couple of pucks, the implants had fallen out. This looked ugly and could cut someone. Soon most of the pucks had missing inserts, and Dad was beside himself. He immediately called the manufacturer, and they had a heated discussion about rubber glue, or more accurately, glue for rubber. Two or three weeks later a couple of boxes of new pucks showed up. Not willing to wait, the OPTs whacked the pucks around the driveway. Alas, the same result: little pieces of orange puck edge all over the place.

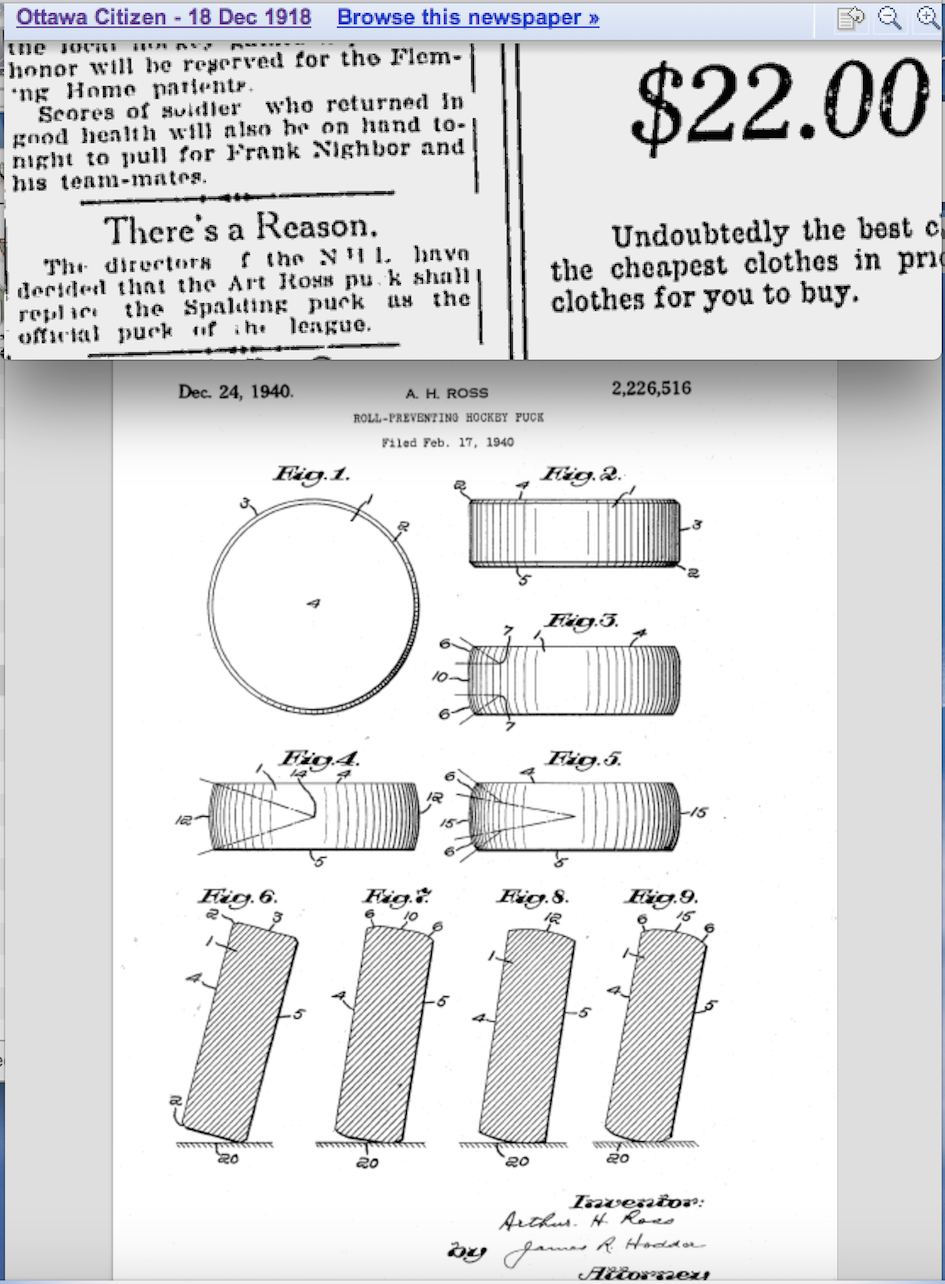

In case you haven’t read my book yet (and if not, why not?!?), the NHL first started using Art Ross’s puck design during its second season of 1918-19. The bevelled edges reducing rolling and injuries, but the NHL didn’t always stick with it. The advent of artificial rubber during World War II improved Ross’s design. He received a U.S. patent in 1940 and the new Ross-Tyer puck was adopted as the NHL’s official puck before the 1940-41 season. Ross’s puck patent has long since expired, but the basic design has never really changed.

Great story, Eric, and a new one for me!

As an OPT of about 50 years ago, I can attest to the fact that every word of this crazy story is true!