With the death of 98-year-old Milt Schmidt on January 4, 2017, the distinction of being the oldest living NHL player falls upon John (Chick) Webster. It was a possibility he had already discussed with his son, Rob. “He told me, ‘This is probably my best record,’” said Rob with a chuckle when we spoke on the phone last week.

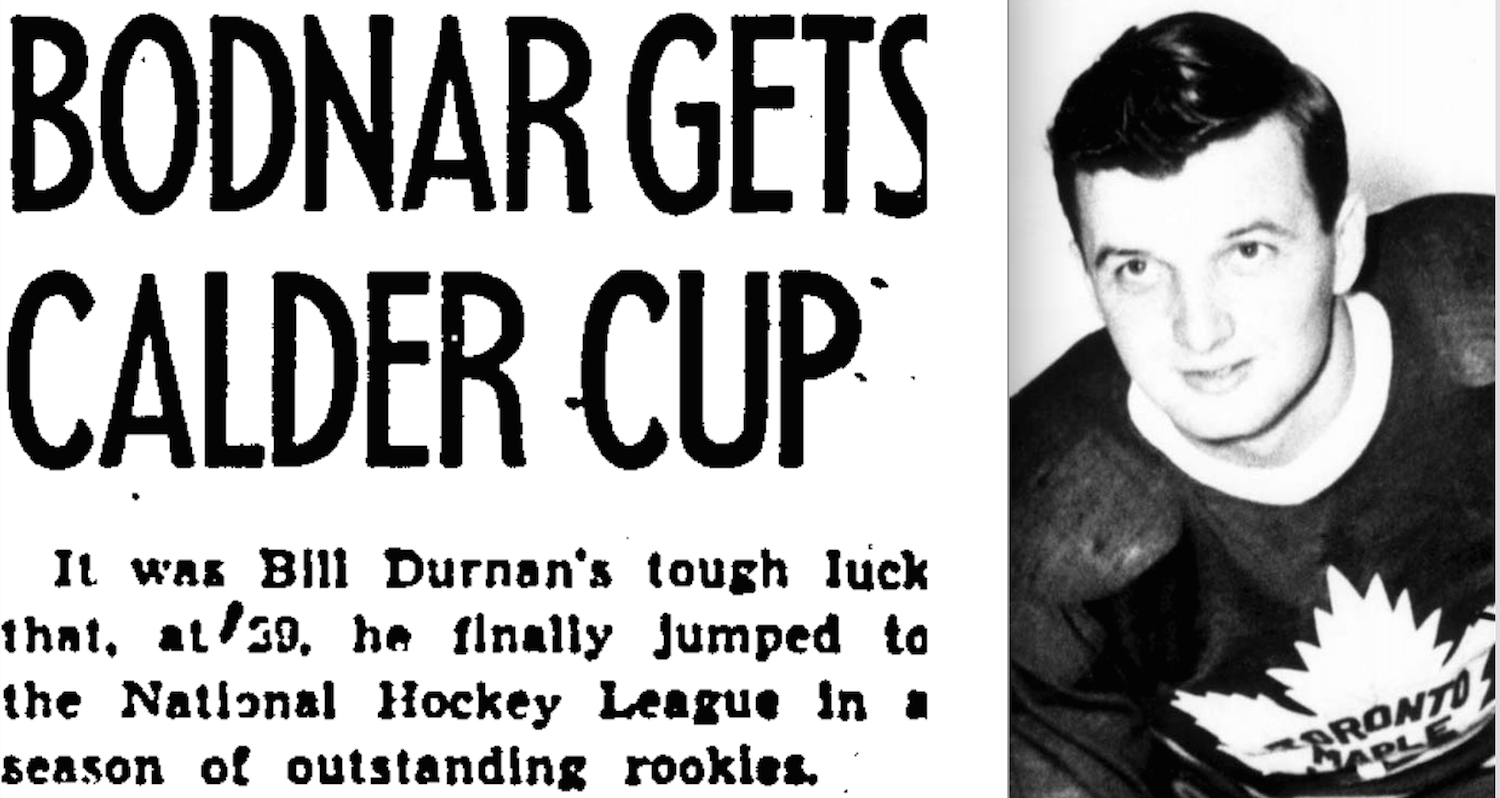

Webster, who recently turned 96, was just being modest. Though he only played 14 games in the NHL back in 1949-50, and never scored a point, Webster (who earned the nickname Chick because of his fondness for Chiclets gum) had a remarkable, and long, career.

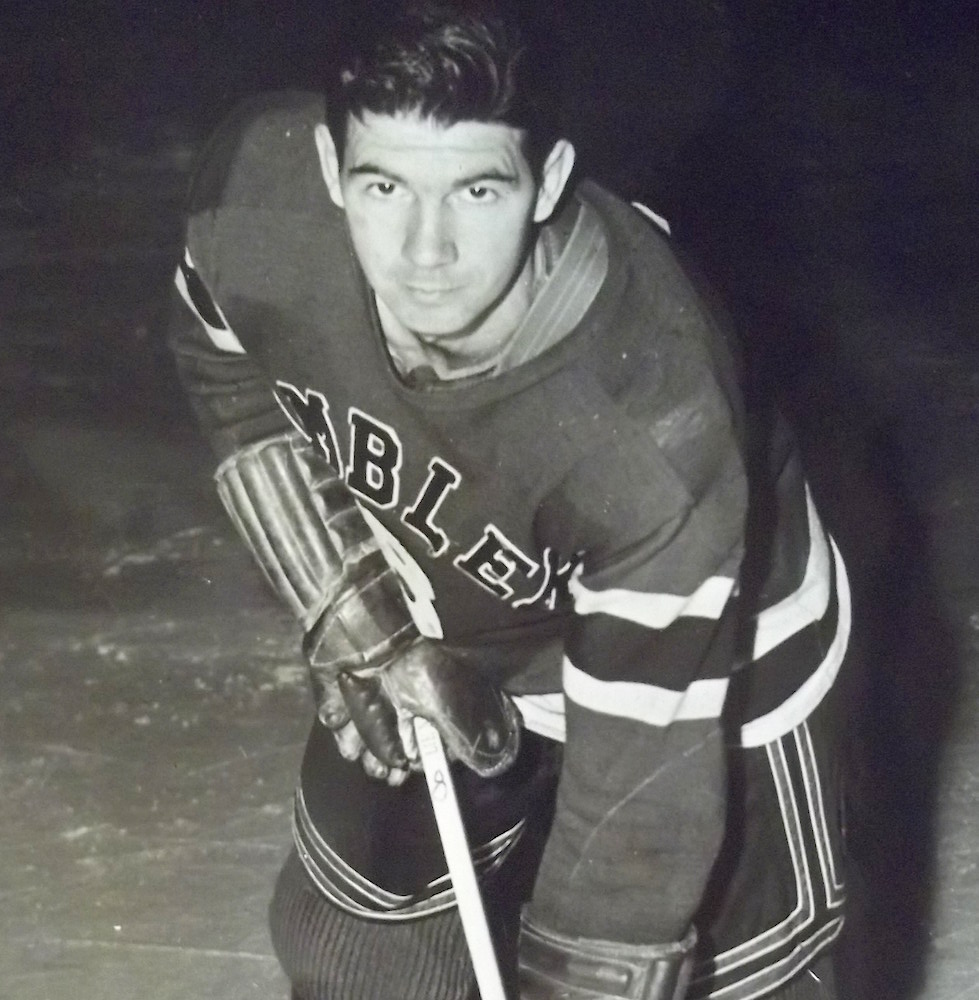

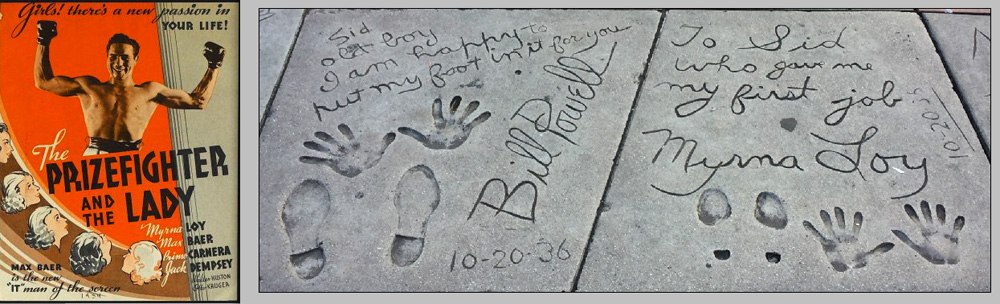

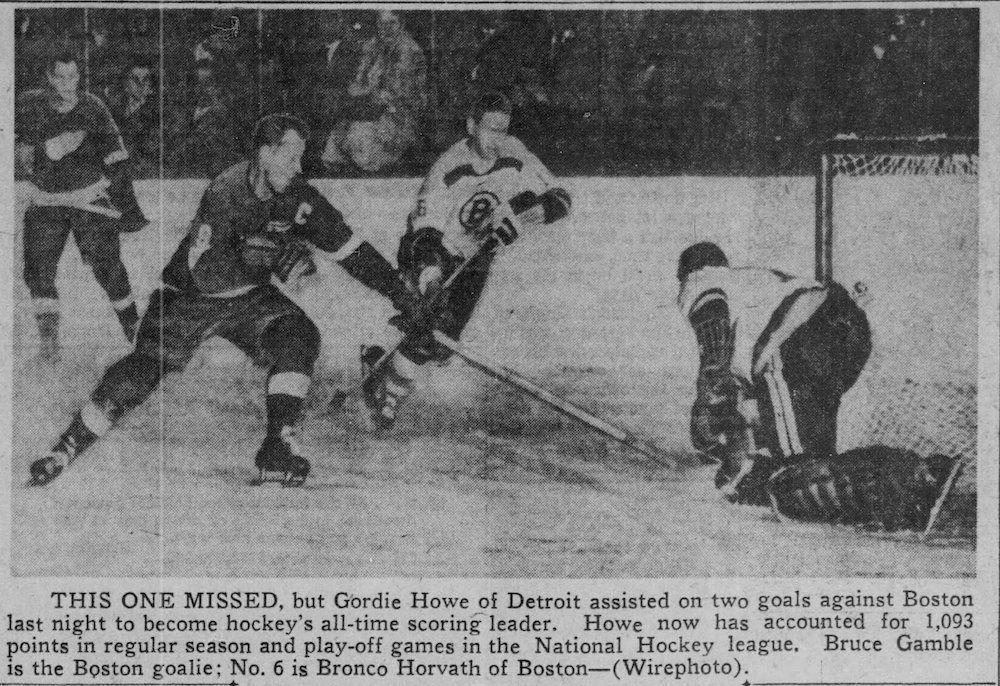

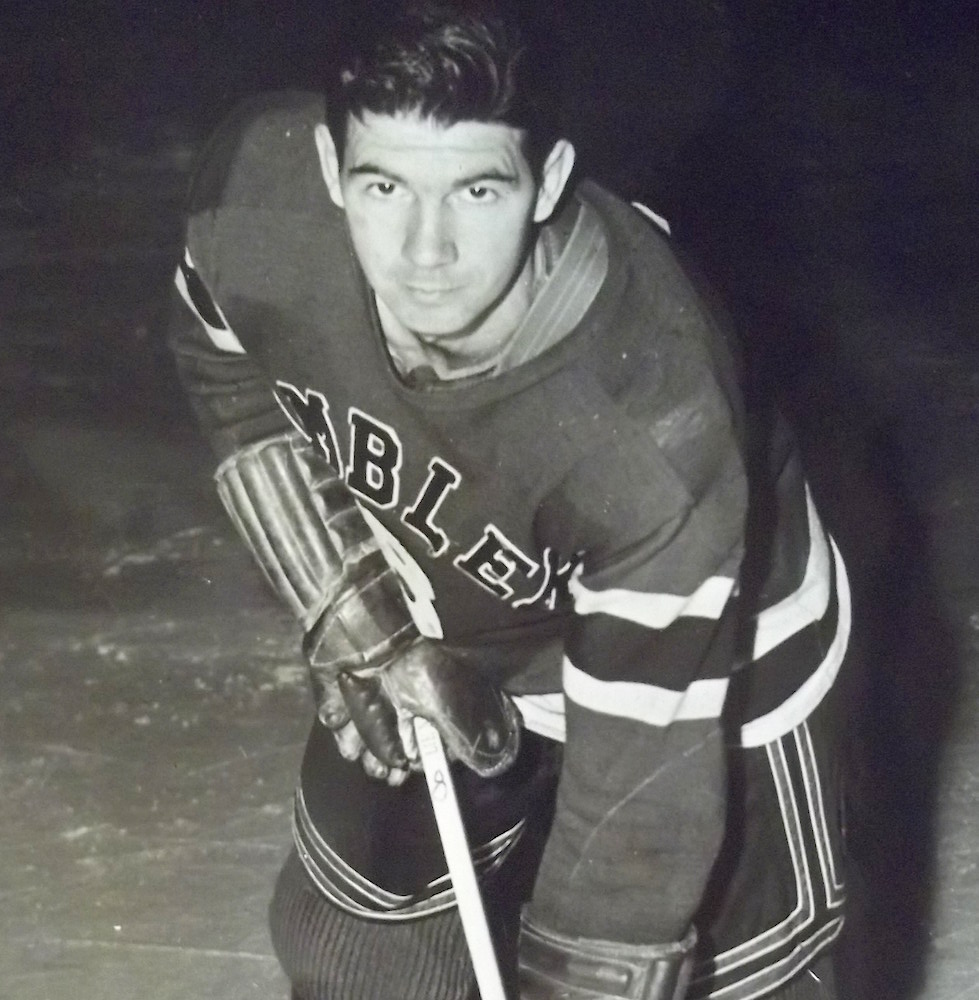

Chick Webster with the New Haven Ramblers, courtesy of Rob Webster.

Chick Webster with the New Haven Ramblers, courtesy of Rob Webster.

John Webster was born in Toronto on November 3, 1920. “I don’t even think his parents knew that he and his brother [Don, who would play for the Maple Leafs in 1943-44] were serious about hockey until they reached juniors,” said Rob. After three years in the OHA with the Toronto Native Sons, Chick attended his first NHL training camp with the Boston Bruins in the fall of 1940. Not only did he meet Milt Schmidt at the camp in Hershey, Pennsylvania, he briefly replaced him during practice centering Woody Dumart and Bobby Bauer when Schmidt hurt his ankle.

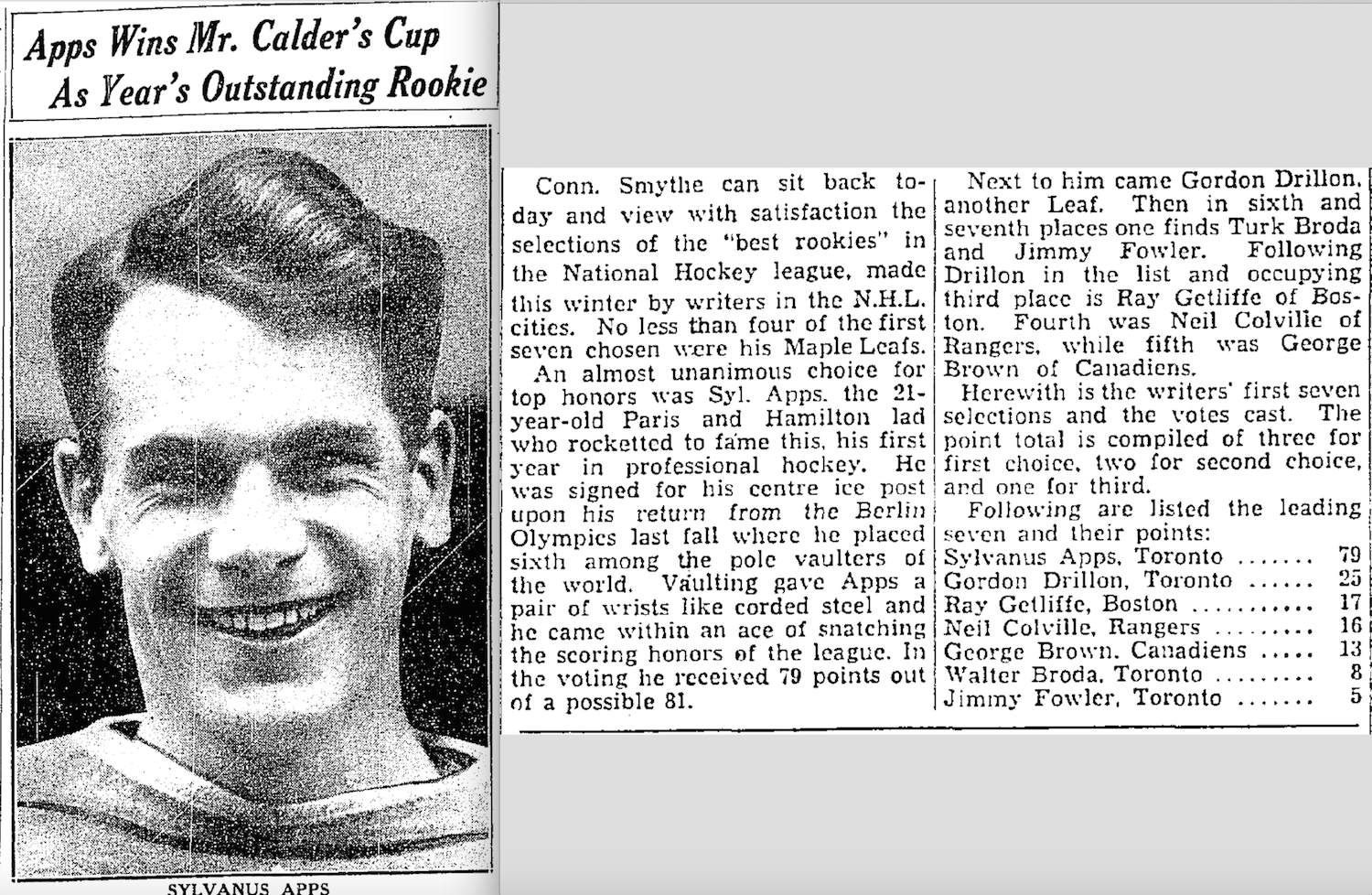

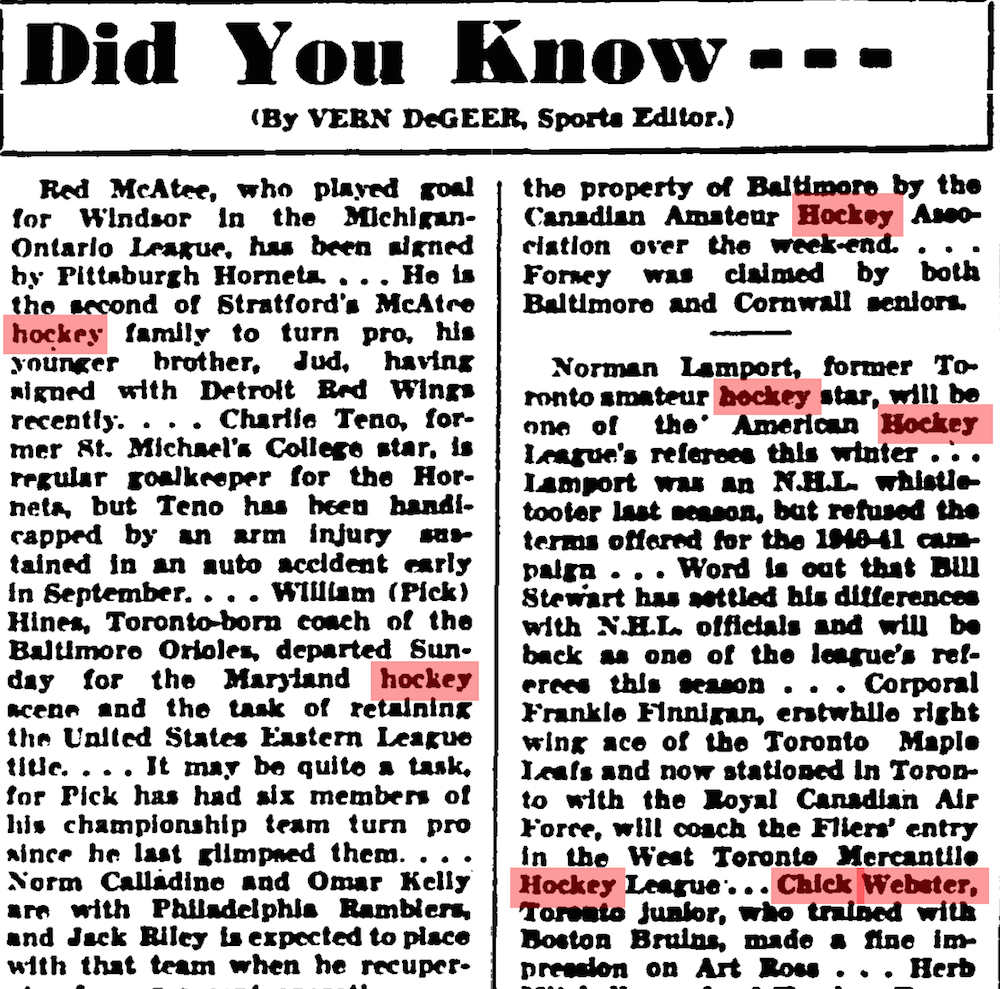

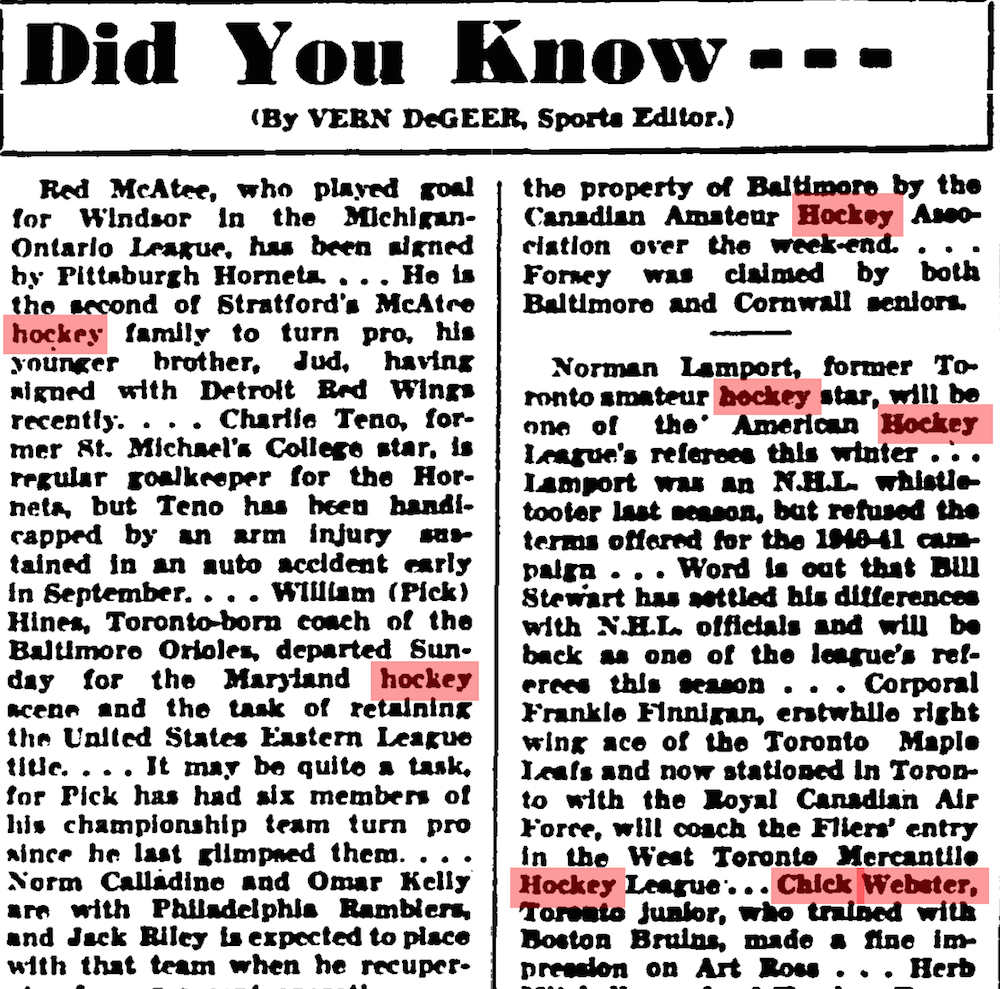

Writing in the Globe and Mail on October 28, 1940, Sports Editor Vern DeGeer notes that Webster, “made a fine impression on Art Ross.” Still, Webster expected to be sent back to Toronto to return to the Native Sons. However, having signed the C-Form that would bind him to Boston until they decided otherwise, Webster was sent by the Bruins to Baltimore of the Eastern Amateur Hockey League for the 1940-41 season.

Globe and Mail, October 28, 1940.

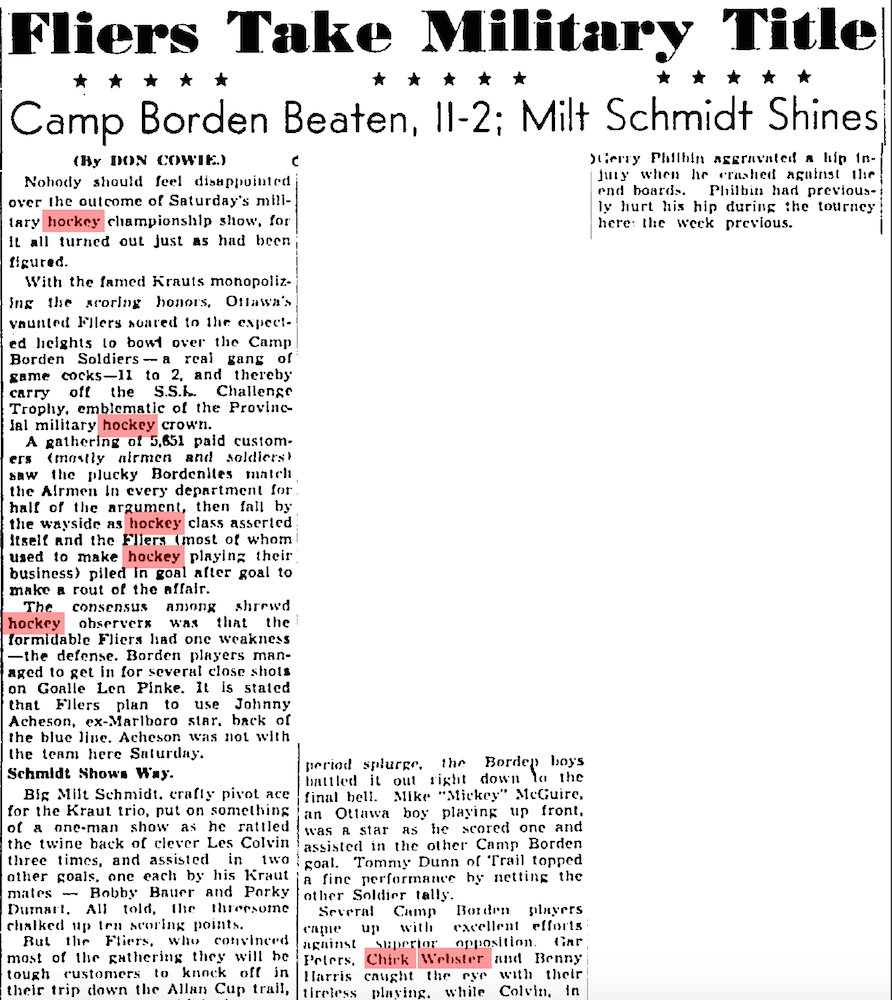

By the following year, regulations established during War time made it difficult for many Canadian men to cross the border. Webster remained in the Toronto area for the 1941-42 season, and soon enlisted with the Canadian army. He encountered Schmidt again in March of 1942 when Webster’s Camp Borden team lost an 11-2 decision to the Kraut Line’s Ottawa RCAF Flyers. “I don’t remember that,” Chick admitted to me, but he does recall hooking up with them all again for a game in England. “I had to borrow skates from the rink for that one,” he says.

Globe and Mail, March 9, 1942.

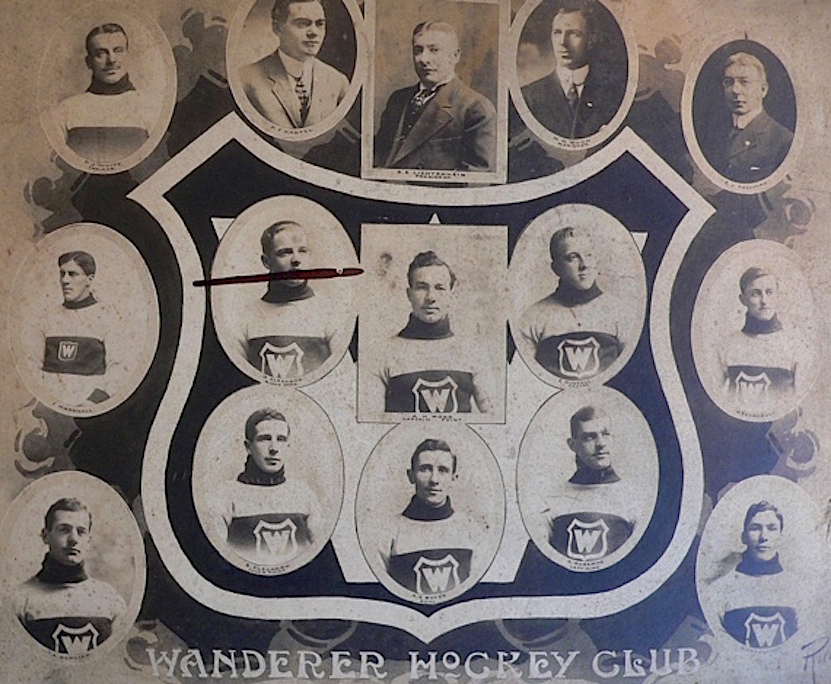

Before he was sent overseas, Webster spent the 1942-43 and 1943-44 seasons playing hockey for the Army with the Petawawa Grenades. “Turk Broda was our goalie,” he remembers. (The once and future Leafs great played with Petawawa in 1943-44.)

Army team at Camp Petawawa. Chick Webster is in the front row, third from the right.

Turk Broda is not present, so this is likely 1942-43. Courtesy of Rob Webster.

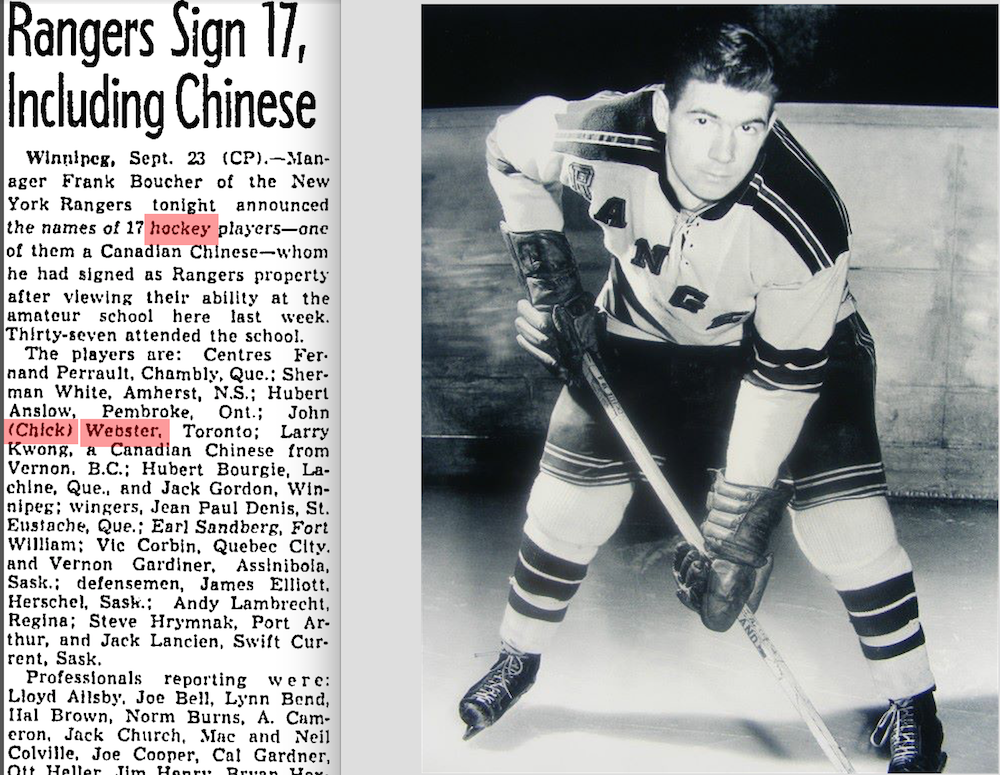

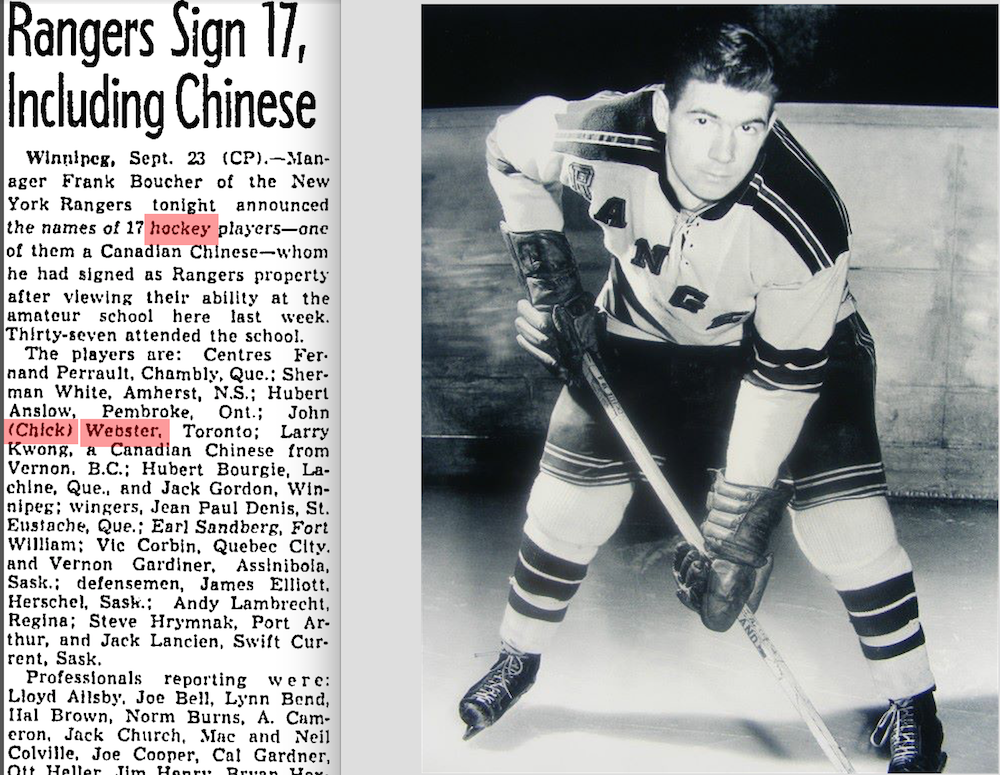

When he got back to Toronto after the end of World War II, Webster was 25 and thought he was too old for a hockey career. His friend Jack Riley (who passed away last summer at the age of 97) convinced him otherwise. After playing briefly with the Uptown Tires team in the Toronto Mercantile League during the early winter of 1945-46, Webster returned to Baltimore to join Jack Riley with the Clippers in the EAHL. His play was impressive enough to attract the attention of the New York Rangers, and he was one of 37 players invited to a Rangers tryout camp in Winnipeg before the next season. On September 23, 1946, Rangers GM Frank Boucher announced that 17 players from the camp had been signed by the club – including Chick Webster.

Webster was assigned to the New York Rovers of the EAHL. “Most of the guys there were just out of juniors, so I think I was a big help to the coach.” But after just a few games, he was promoted to the New Haven Ramblers of the American Hockey League, where he played for nearly three full seasons.

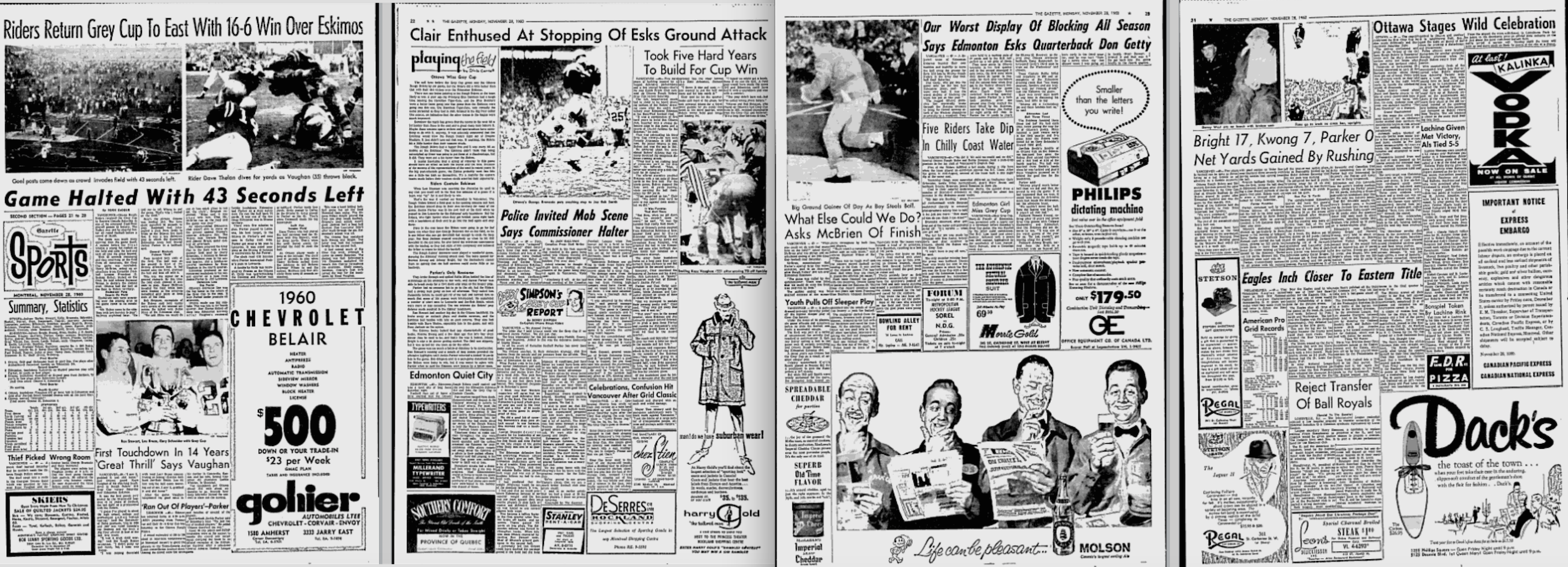

Globe and Mail, September 24, 1946. Photo courtesy of Rob Webster.

Globe and Mail, September 24, 1946. Photo courtesy of Rob Webster.

“I was 30 when the Rangers finally brought me up,” Chick said. “Some guy got hurt.” Actually, it was December of 1949 and he had just recently turned 29. But on January 15, 1950, it was Webster who got hurt. He remembers it as a broken wrist, though other sources say a broken hand. After sitting out a bit, he finished the season in New Haven wearing a leather cast on his arm. His NHL career was over, but he was far from through with hockey.

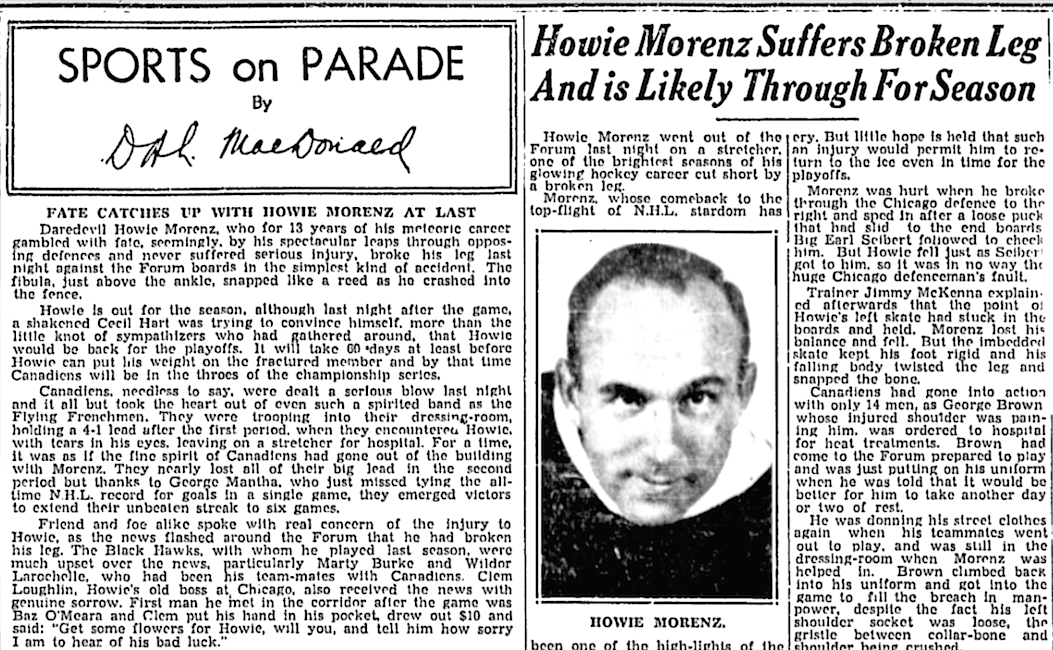

“The best team I ever played on,” says Webster, “was the Cincinnati Mohawks.” This was in the AHL in 1951-52. “We had Buddy O’Connor and Pat Egan. Emile Francis was our goalie.” He still keeps in touch with Francis, and is occasionally in contact with another Mohawks player who went on to the NHL, Ivan Irwin.

Chick Webster enters the Cincinnati Mohawks dressing room and

Chick Webster enters the Cincinnati Mohawks dressing room and

shakes hands with a young boy. Film provided by Paul Patskou.

“He seemed to be one of those players who could always be in the play,” says Irwin of his former teammate. “Winning was important to him. It was important to all of us. He was a hustler.”

Webster’s worst experience in hockey came a year later, playing with the Syracuse Warriors in 1952-53. Eddie Shore ran the team. He’d been a huge star in the NHL, but he was a tyrant as a minor league owner and coach. “Shore was a real, real, terrible guy,” Chick says. “If you were sick, or didn’t go on the trips out of town, he’d ask, ‘did you skate?’ I told him I couldn’t get on the ice because the rink was being used. He said, ‘there’s plenty of snow on the ground. You should have gone out on the road and skated.’ Then he fined me.”

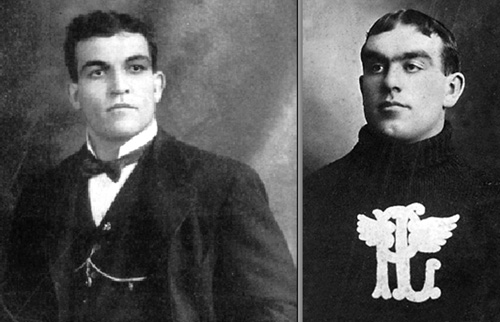

Chick Webster now and then. Signing a photo that has been mailed to me

and the earliest hockey photo of him, Toronto 1934. Courtesy of Rob Webster.

That 1952-53 season would be Webster’s last as a pro, but he continued to play amateur hockey in the Toronto area in Stouffville and Willowdale until the mid 1960s. In 1970, he moved to Mattawa, Ontario, where he played oldtimers hockey well into his 70s. He remains, as his son Rob says, feisty and independent and still living on his own at age 96.

It was a treat to speak with him.

For more on Chick Webster, please see the following stories:

Puckstruck 2017

North York Mirror 2016

North York Mirror 2017

The Hockey News 2017

Dennis Kane 2014

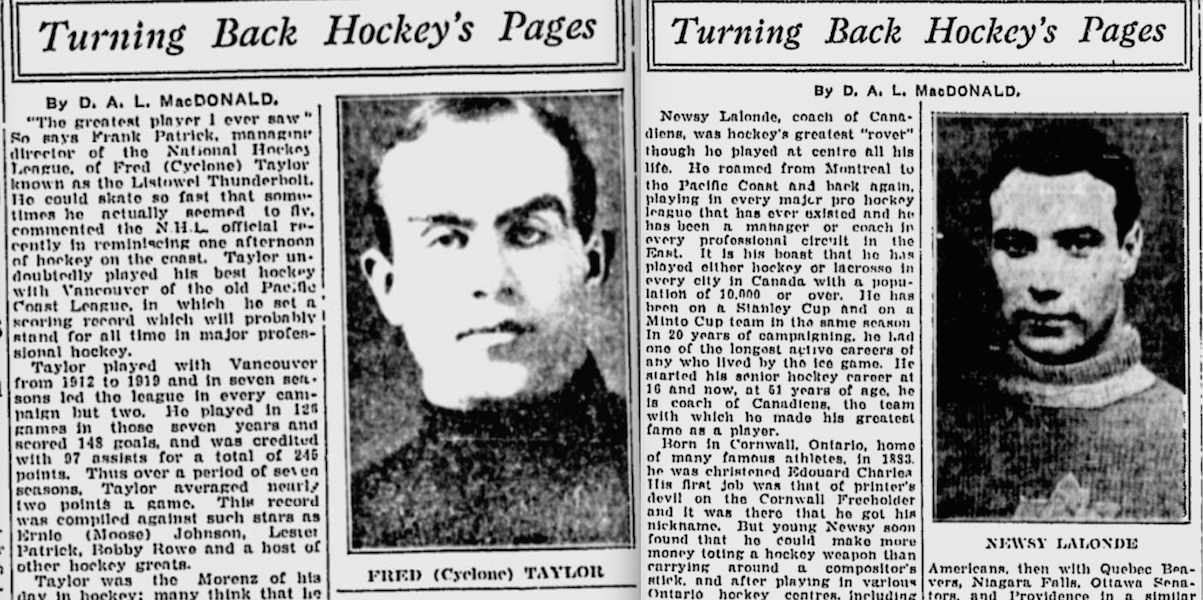

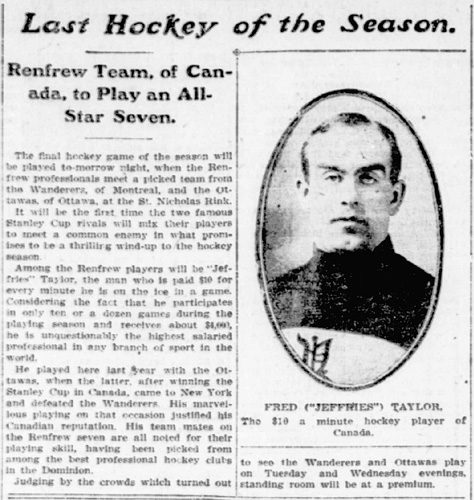

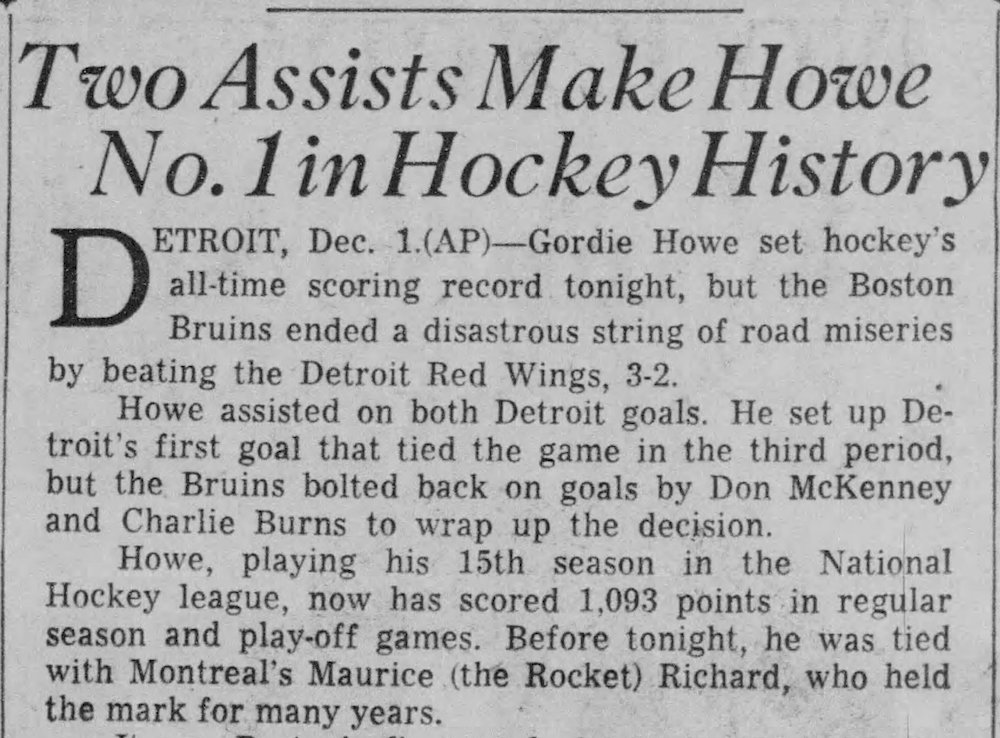

Article in The New York Daily Tribune on March 18, 1910, when Taylor

Article in The New York Daily Tribune on March 18, 1910, when Taylor

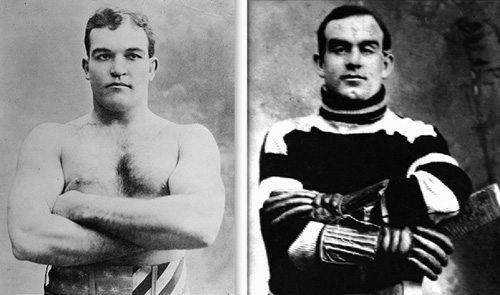

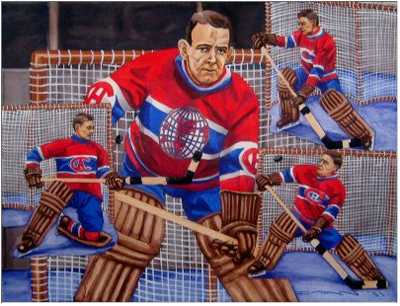

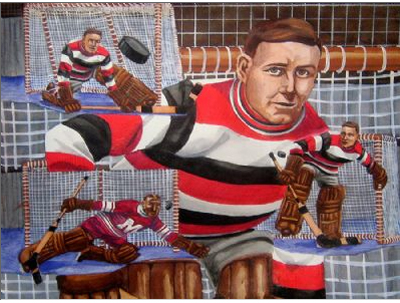

Paintings by Darrin Egan. Visit him on

Paintings by Darrin Egan. Visit him on  Contact Darrin at: inthebluepaint@gmail.com

Contact Darrin at: inthebluepaint@gmail.com Chick Webster with the New Haven Ramblers, courtesy of Rob Webster.

Chick Webster with the New Haven Ramblers, courtesy of Rob Webster.

Globe and Mail, September 24, 1946. Photo courtesy of Rob Webster.

Globe and Mail, September 24, 1946. Photo courtesy of Rob Webster. Chick Webster enters the Cincinnati Mohawks dressing room and

Chick Webster enters the Cincinnati Mohawks dressing room and