All these years later, it seems there are still plenty of people who hate Eric Lindros.

Spoiled and arrogant? A self-entitled jerk? Maybe. (I don’t know him.) And we’re not going to go into the whole Koo Koo Bananas incident. (I wasn’t there, and he’s certainly not the only rich young man – athlete or not – to act like a jerk. Not that that excuses anything!) But here’s my thinking on Lindros and his parents.

Suppose your son is 18 years old. Just out of high school, or maybe finished a year of university. He knows what he want to do … and he’s very good at it. Doesn’t matter if it’s a lawyer or a plumber or what. Say it’s a plumber. He’s drafted by a plumbing firm. It’s based thousands of miles from where you live, and he probably can’t earn as much money there as he could somewhere else. But he HAS to go. Or, at least, everyone believes he’s got to. And later, if the plumbing firm wants, they’ll trade him somewhere else. Or just let him go.

Would we accept that?

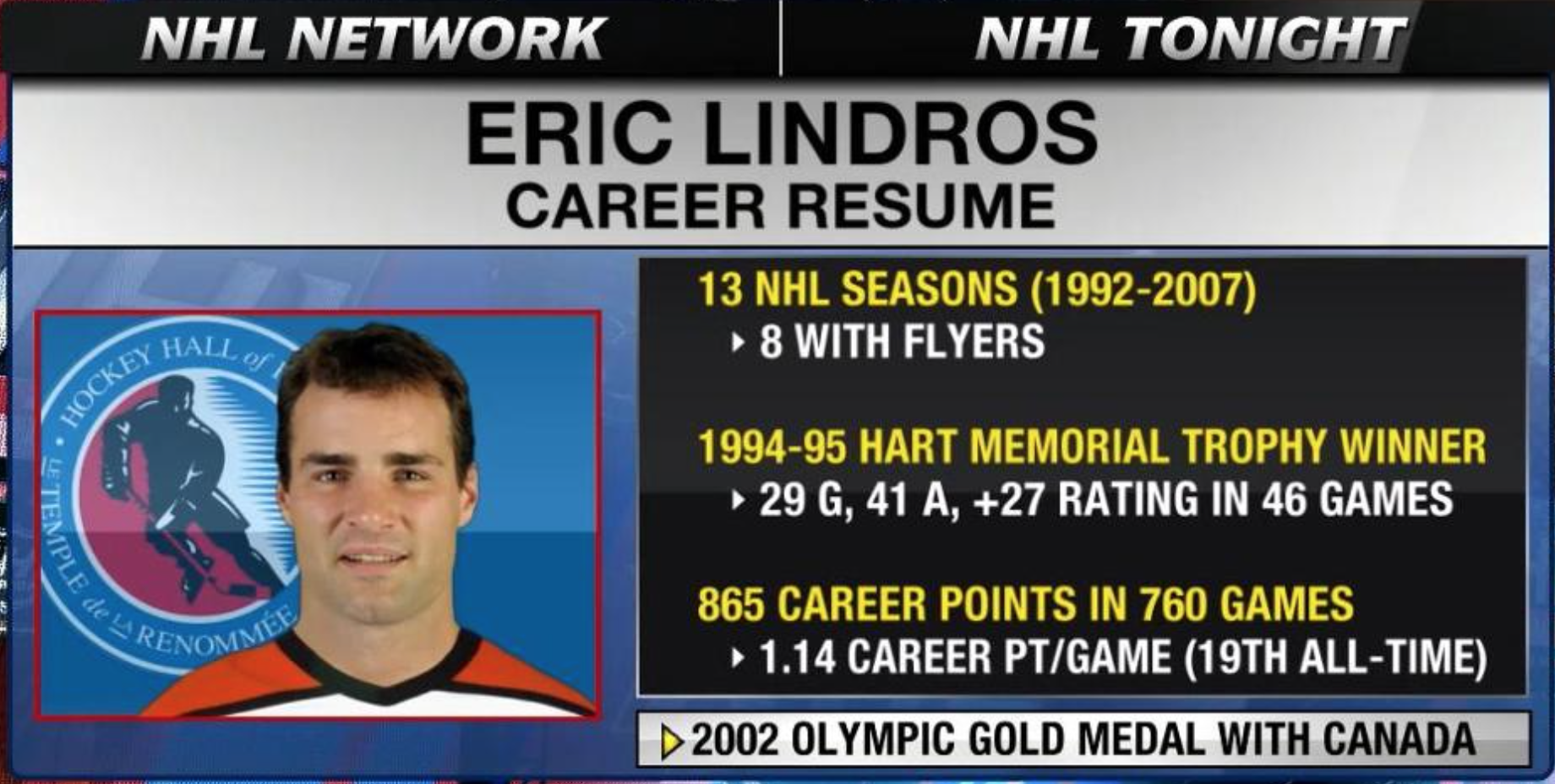

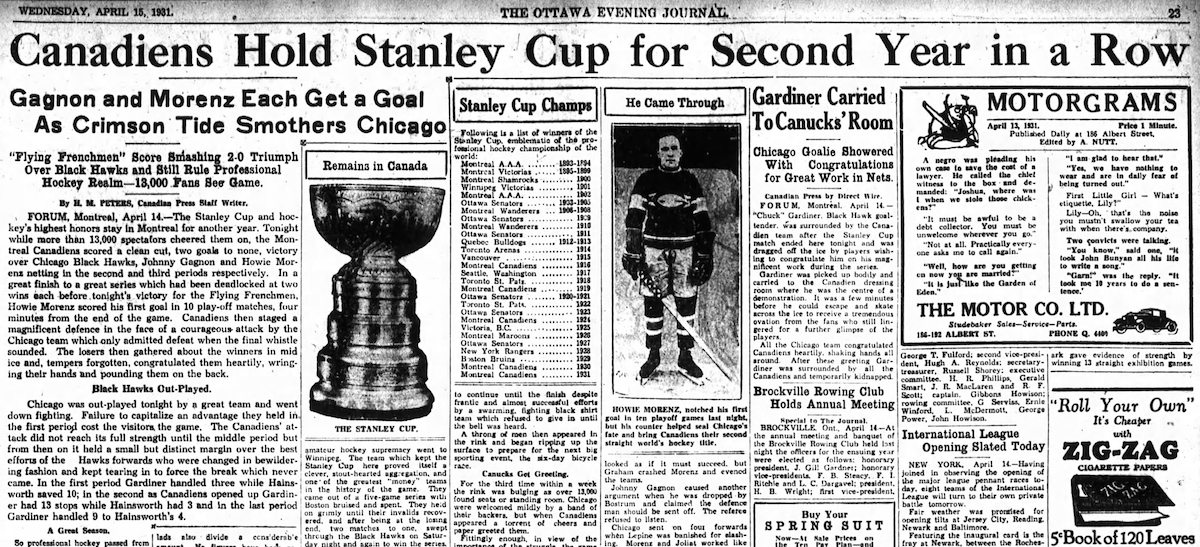

Announcement Monday on the NHL Network that Eric Lindros had been elected

to the Hockey Hall of Fame. He’ll be inducted in November with Rogatien Vachon,

Sergei Makarov and Pat Quinn.

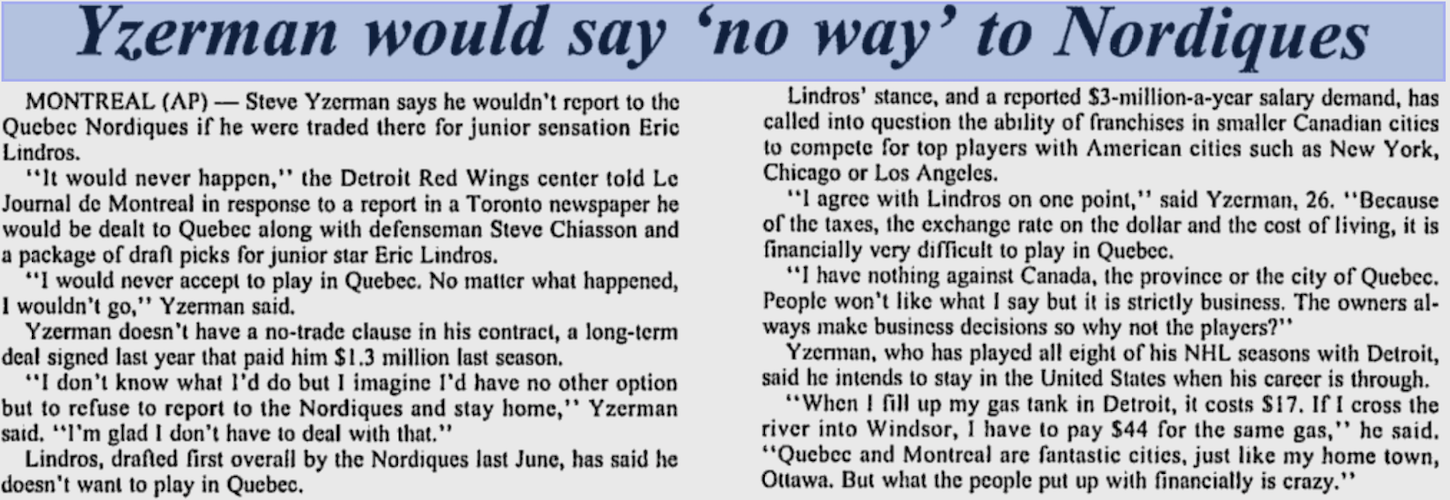

The Lindros family certainly rocked the boat when Eric refused to go to Quebec (and Sault Ste. Marie before that). Lindros said the other day that the reasons had nothing to do with the city, the province or its culture, but with personal differences – likely with Marcel Aubut, who was CEO of the Nordiques at the time and recently stepped down as president of the Canadian Olympic Committee over allegations of sexual harassment.

Whether or not that was really the case, or just revisionist thinking, the Lindros family was fortunate to be in a position where they weren’t like the old-time farm boys or miner’s sons looking for their only way out. Eric Lindros and his parents wanted to have a say in his future. I’m pretty sure my parents would have wanted the same with me. As it was, my family certainly did a lot to help when I was getting started in my work. Wouldn’t you do the same for your kids if you were in a position to? And yet people hated the Lindros family for it. Many still do.

But, of course, sports aren’t like being a plumber. Or a lawyer. Or a writer. These athletes should consider themselves lucky that they get paid to play games! They should do what they’re told!

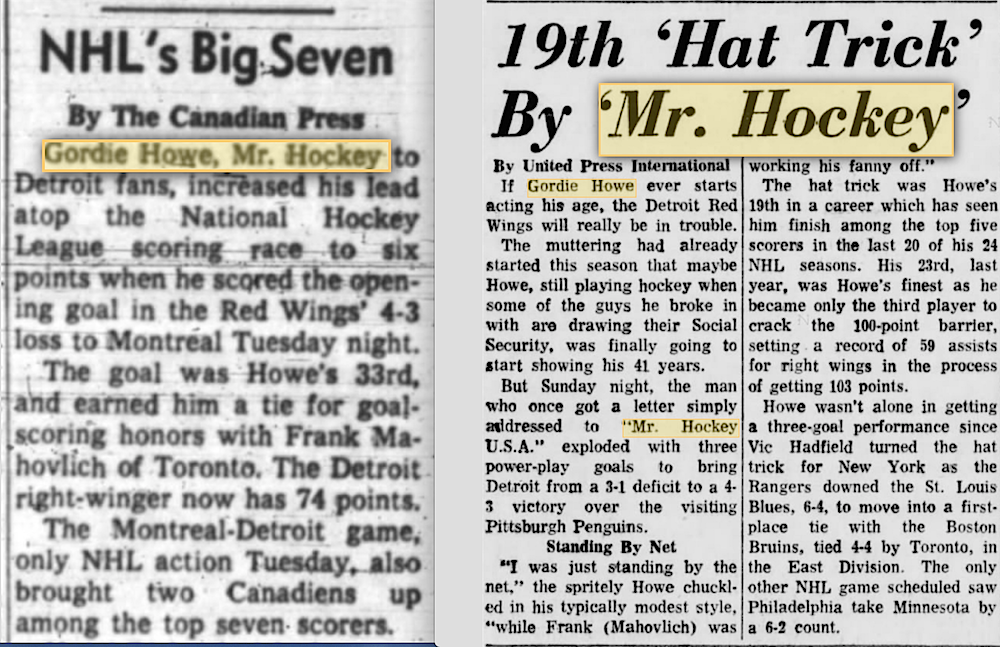

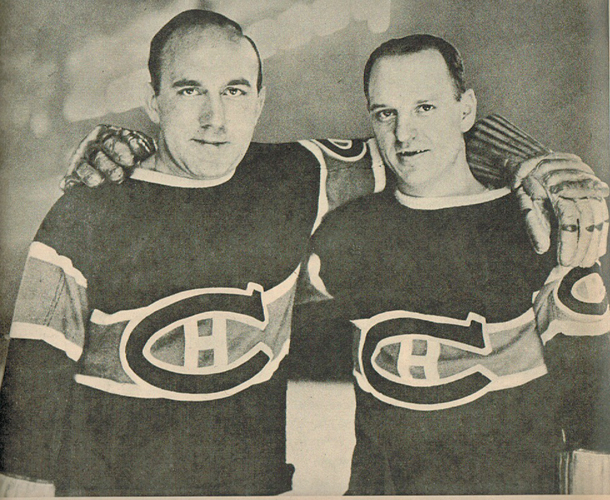

And yet, we all look back at Gordie Howe and we think how terrible it was that such a great athlete was taken advantage of so badly by the people in charge of the game he excelled at. A team jacket as a signing bonus; a thousand dollar raise each year; a salary kept artificially low so that other teams could say to their stars, “how can we pay you more than Gordie Howe?”

It was all about who controlled the money, and who had the power. That’s why guys like Punch Imlach and Jack Adams could walk around with train tickets to minor league towns sticking out of their pockets, terrifying young players into toeing the line.

Yes, things are better now. Players can make tens of millions of dollars. But there’s still no one in management really looking out for their best interests … unless they also serve the best interests of the team. As I’ve said before, I do have a hard time rooting for people half my age making more money per game than I do in a year, but if there really is that much money out there, I’d rather see the players getting their fair share.

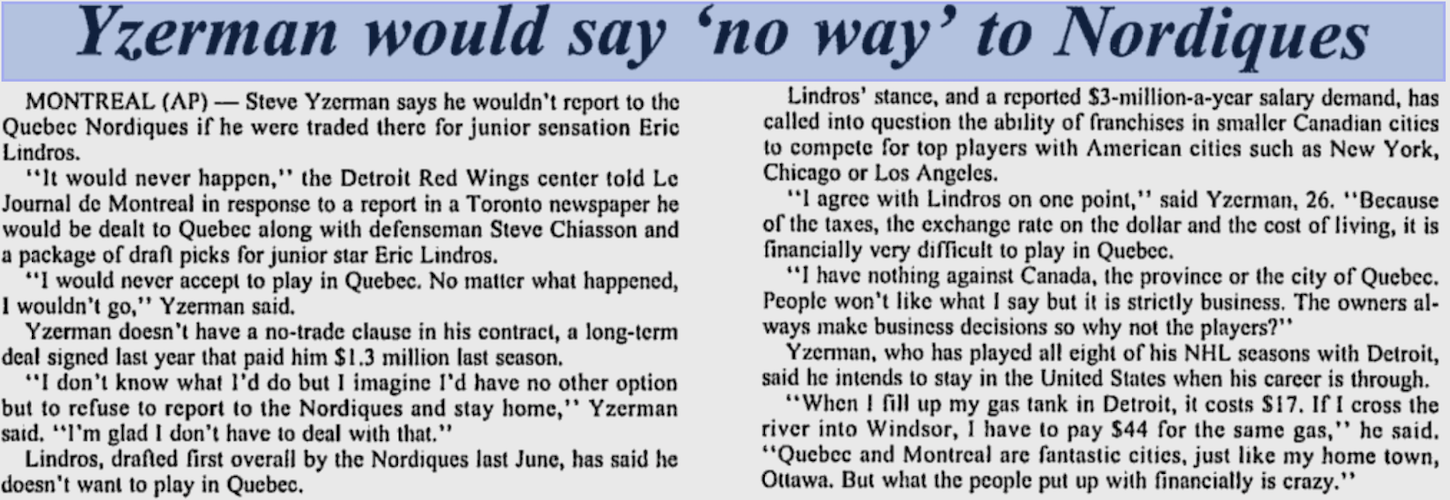

In this Associated Press report from Montreal on August 16, 1991 – two months after

that year’s NHL Draft – Steve Yzerman said he didn’t want to play in Quebec either.

All that aside – and you’re certainly free to disagree with me – there’s still the question of whether or not Eric Lindros the player is worthy of induction to the Hockey Hall of Fame.

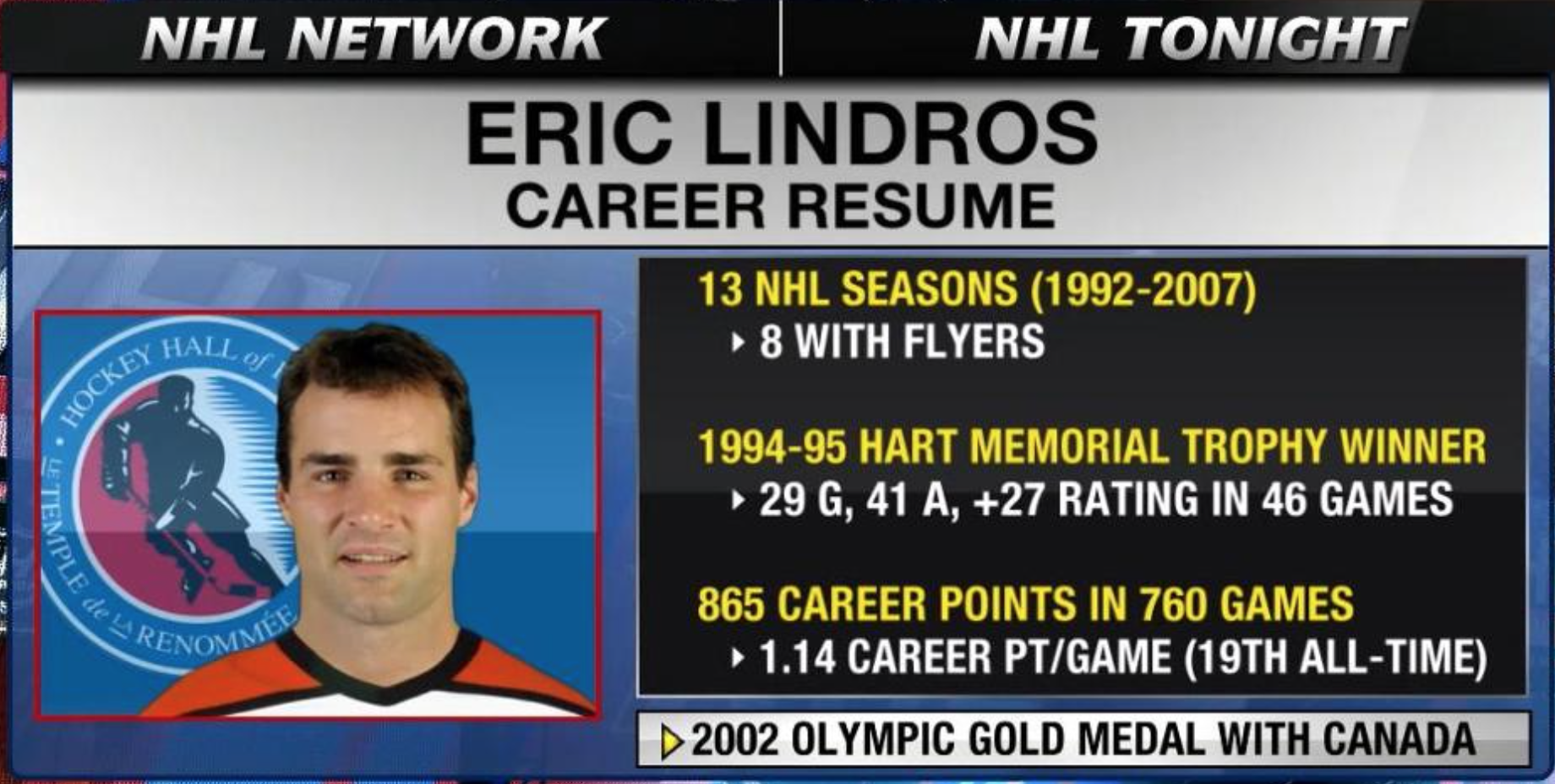

Love him or hate him, in the early days of his career – before all the concussions – Lindros was certainly living up to “The Next One” hype. In his first six seasons, from 1992 to 1998, he played 360 games (injuries had already cost him nearly 100 games) and had accumulated 507 points.

In the NHL Official Guide & Record Book, there is a listing for the Highest Points-Per-Game Average, Career (Among Players with 500-Or-More Points). At the time Lindros had reached those 507 points, his points-per-game average was 1.408. If he’d kept that up for his entire career, Lindros would still be a long way behind Wayne Gretzky (1.921) and Mario Lemieux (1.883), who hold down the top two spots, but he would only be slightly behind #3 Mike Bossy (1.497) and would rank ahead of the 1.393 mark of the #4 player … Bobby Orr.

If Lindros had managed to stay healthy enough to play 1,000 games at that scoring pace, he would have had 1,408 points in his career. That would rank him 20th in NHL history despite playing significantly fewer games than anyone else in the top 20 except for Mario Lemieux, who ranks eighth all time with 1,723 points while playing only 915 games.

Even at his final career scoring pace of 1.138 (865 points in 760 games), which was much diminished due to his injuries, if Lindros had managed to reach 1,000 games his 1,138 points would place him 54th in NHL history (two spots ahead of Bossy) despite playing far fewer games than everybody ahead of him except Lemieux and Peter Stastny (1,239 points in 977 games.)

But, of course, those are pretty big ifs!

I’m not sure the Hockey Hall of Fame should be rewarding anybody for the potential of what might have been … but since Peter Forsberg and Pavel Bure are already in with pretty comparable statistics, and Cam Neely is in with much weaker career numbers, it’s hard to make the case for keeping Lindros out.