This past Sunday (January 28, 2018), The Nature of Things on CBC aired an interesting episode called Champions vs Legends. In it, sports scientist Steve Haake investigated the question: “What if the greatest elite (winter) athletes – present and past – could compete against each other on a level playing field? If competitive conditions were made equal, would today’s stars come out on top? Or would they be beaten by the heroes of the past?”

It’s impossible to truly make the conditions equal, but it was very interesting. If you’re in Canada, you should be able to click here to watch it all online if you choose to. Also, although it DID air last Sunday, the CBC web site currently shows it as airing THIS Sunday. It was joined in progress due to the NHL All-Star Game, so maybe they’re planning to run it again in its entirety?

Don’t bother clicking on the arrow. It’s just a screen shot, not a video link. Sorry!

Among the six segments in the episode was one in which Shea Weber of the Montreal Canadiens tried to match Bobby Hull’s shooting prowess with a retro wooden stick. Weber had his slap shot clocked by radar at 108.5 miles per hour at the NHL All-Star Game a few years ago. But when he used leather gloves and a wooden stick in this episode, the fastest he could manage was 91 miles per hour. When he switched back to his current stick, his shot jumped to 103 mph.

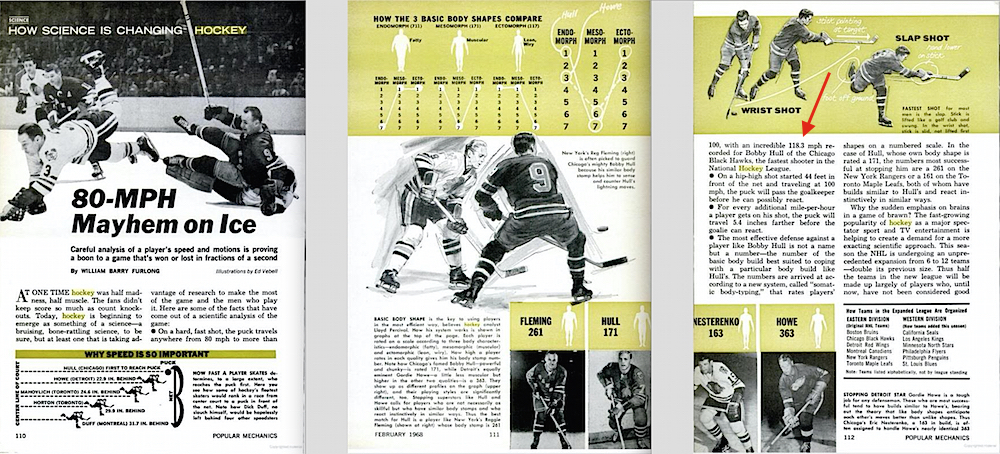

Bobby Hull, as the episode notes, is said to have had his slap shot clocked at 118.3 miles per hour during the 1960s. This was a prominent feature of an article in Popular Mechanics in February of 1968 … though as the show also notes, nothing is said about how Hull’s shot was actually measured. These days, it’s generally conceded that Hull’s shot was never accurately measured, and that any timing device from his era would be unreliable. No doubt he had the hardest slap shot of his era, and likely the hardest of all time up to that point, but it’s hard to believe that Bobby Hull could really have approached 120 mph with a wooden stick in the 1960s. On the other hand, what might have been able to do with a modern carbon fibre stick?!?

This Popular Mechanics article reports Bobby Hull’s slap shot being clocked at 118.3 mph.

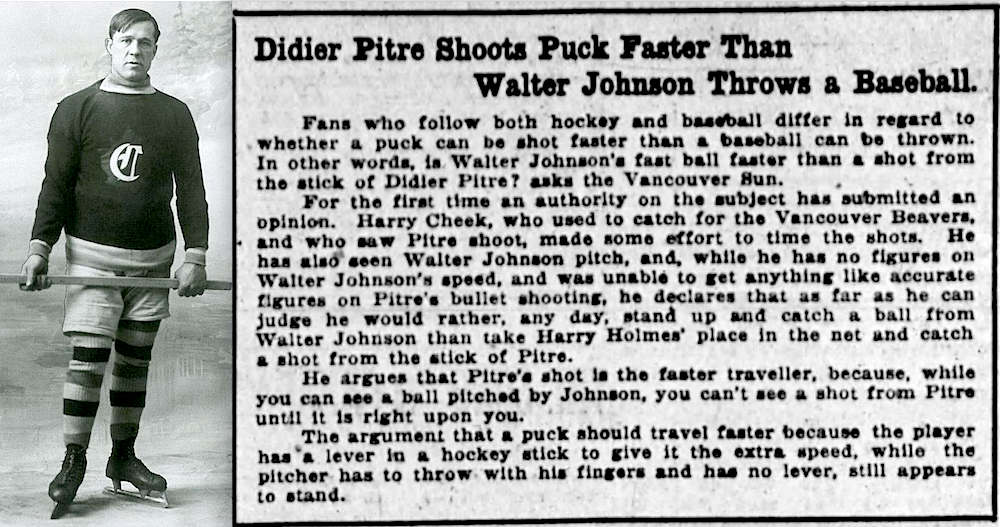

But all this is really just a roundabout way for me to show off a fun clip I found recently in an old newspaper. The article is from The Ottawa Journal on March 30, 1917, picking up a story from The Vancouver Sun. It compares the hockey shot of Didier Pitre to the baseball pitch of Walter Johnson. (Recall that in August of 2016, I posted a story about the documentary Fastball featuring Walter Johnson and the history of measuring baseball’s fastest pitchers.) The comparison is made by Harry Cheek, a journeyman minor league catcher with just two games in the Majors who had recently retired after playing three years in Vancouver.

Didier Pitre is not a particularly well-known name these days, but he was one of the biggest stars in hockey during a 20-year career beginning in 1903. He starred mainly with the Montreal Canadiens from the team’s inaugural season in the National Hockey Association in 1909-10 through 1922-23 in the NHL. In his heyday, he was widely regarded as having the hardest shot in hockey.

It does make sense that the lever quality of a hockey stick would allow a hockey player to shoot harder than a pitcher can throw. Still, it’s hard to imagine Didier Pitre could shoot a puck in 1917 faster than than the 83 miles per hour Walter Johnson had been measured at in 1912 … not to mention the 93 mph the Fastball documentary says that actually translates to. And it’s interesting that Nolan Ryan’s fastball upgrades to the same 108.5 miles per hour as Shea Weber’s best slap shot. These days, I think it would be interesting to know how many players in the NHL can approach 100 miles per hour with their best shot compared to the number of pitchers who can approach 100 mph with their best fastball.

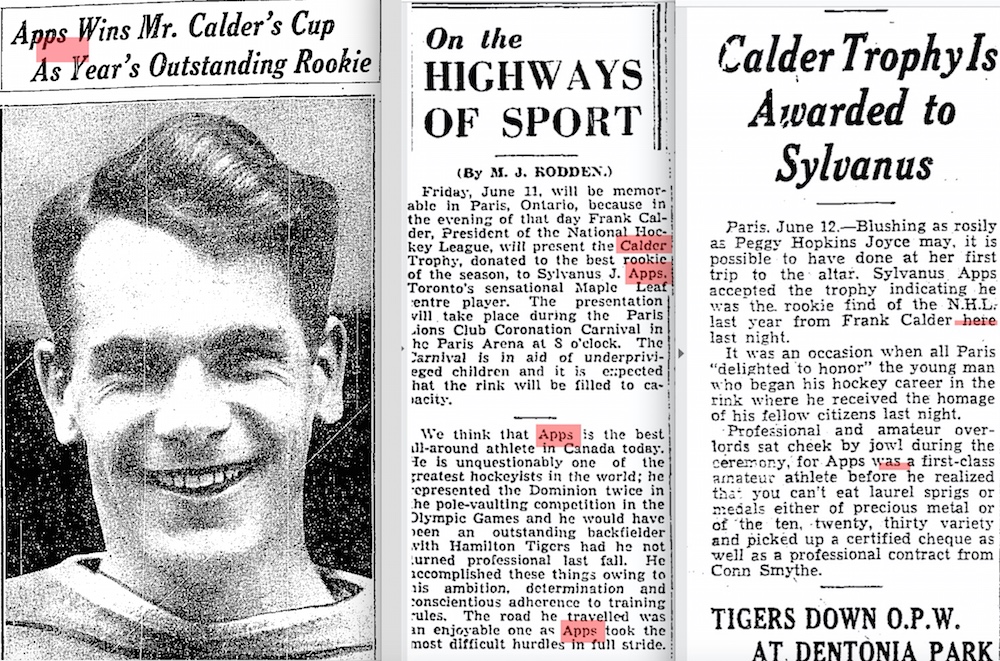

The article on the left is from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on March 24, 1930.

The article on the left is from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on March 24, 1930.