I don’t have a contact file filled with famous names. There are a few. Some I’ve known for a long time; others only recently. Still, it’s always exciting for me whenever I hear from any of them.

The first time I heard from Scotty Bowman was about five years ago. Phil Pritchard from the Hockey Hall of Fame emailed me to say that Mr. Bowman had pointed out an error I had made in his coaching record for my book Stanley Cup: 120 Years of Hockey Supremacy. It was basically little more than a typo, but I was horrified! Mistakes happen, but this one was pretty sloppy and, well, it was Scotty Bowman, the winningest coach in NHL history. He certainly had a reputation for being pretty tough with some pretty talented hockey players. How was he going to treat me?

I wrote a very apologetic note and got a very nice reply. That was about as far as it went, until a year or so later when I was deeply into working on Art Ross: The Hockey Legend Who Built the Bruins. I had just read a biography of Boston Bruins legend Dit Clapper by Stewart Richardson and Richard LeBlanc, which mentioned that Bowman and Clapper had been close when Bowman was starting out as a coach in Peterborough. So, I wrote again and asked Mr. Bowman if he’d ever heard any interesting stories from Dit Clapper about Art Ross.

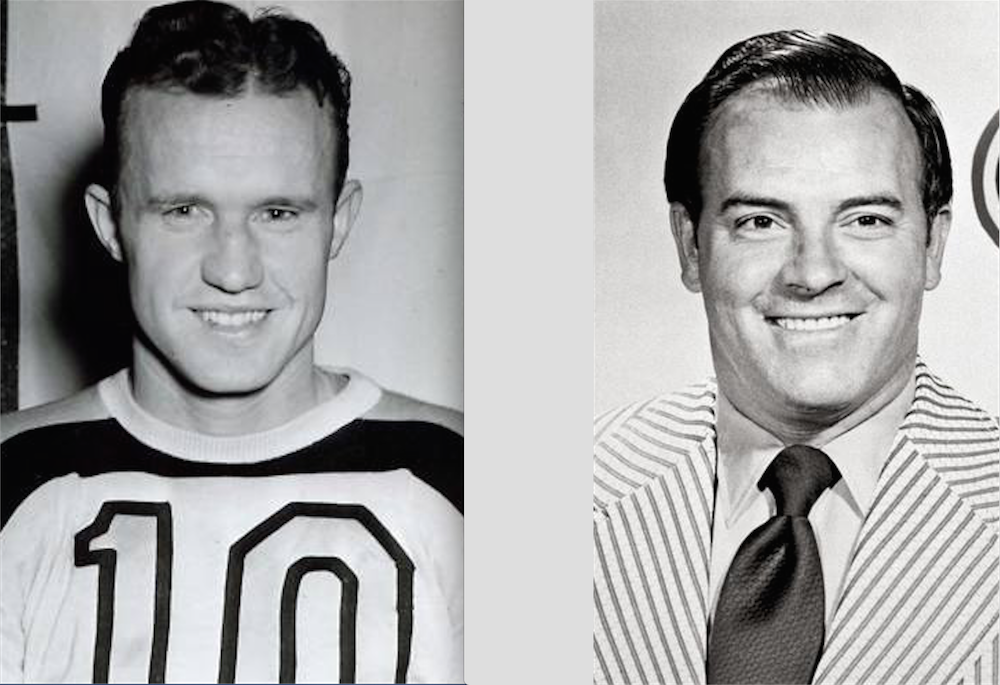

Boston’s Bill Cowley was the childhood hero of future Canadiens coach Scotty Bowman.

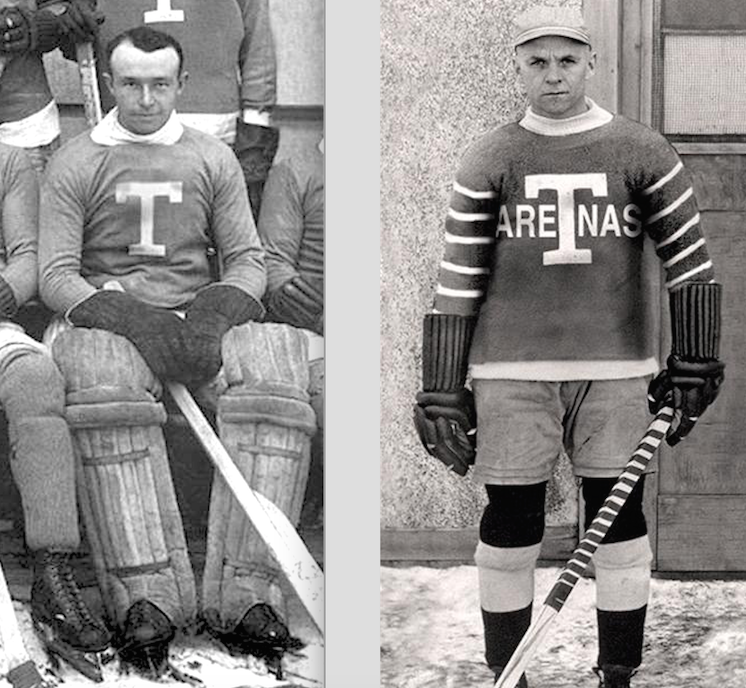

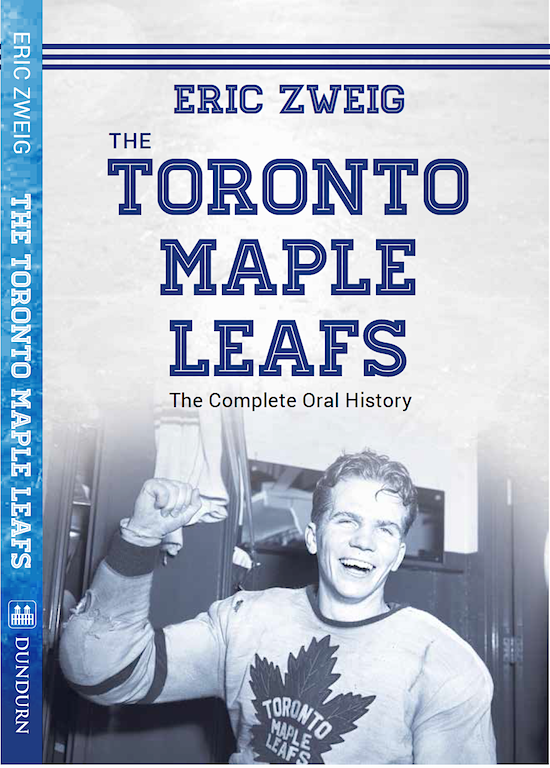

That evening, Scotty called me at home. (Very exciting!) No, he said, he hadn’t heard any stories from Dit, but when he was working with Lynn Patrick for the St. Louis Blues, Patrick had told him some stories that he was happy to share. I was thrilled to be able to include them in the book. Scotty later read and enjoyed an advanced copy and provided a very nice “blurb” for the back cover. He’s done the same for my upcoming book The Toronto Maple Leafs: The Complete Oral History.

Scotty Bowman celebrated his 84th birthday earlier this week. Dave Stubbs wrote a very entertaining piece with Scotty on the NHL web site for a Q&A feature called Five Questions With… After I read it, I sent Scotty a short email wishing him a happy birthday and saying that I had enjoyed the answer he gave saying that Art Ross was the one hockey person from any era he would like to spend some time with.

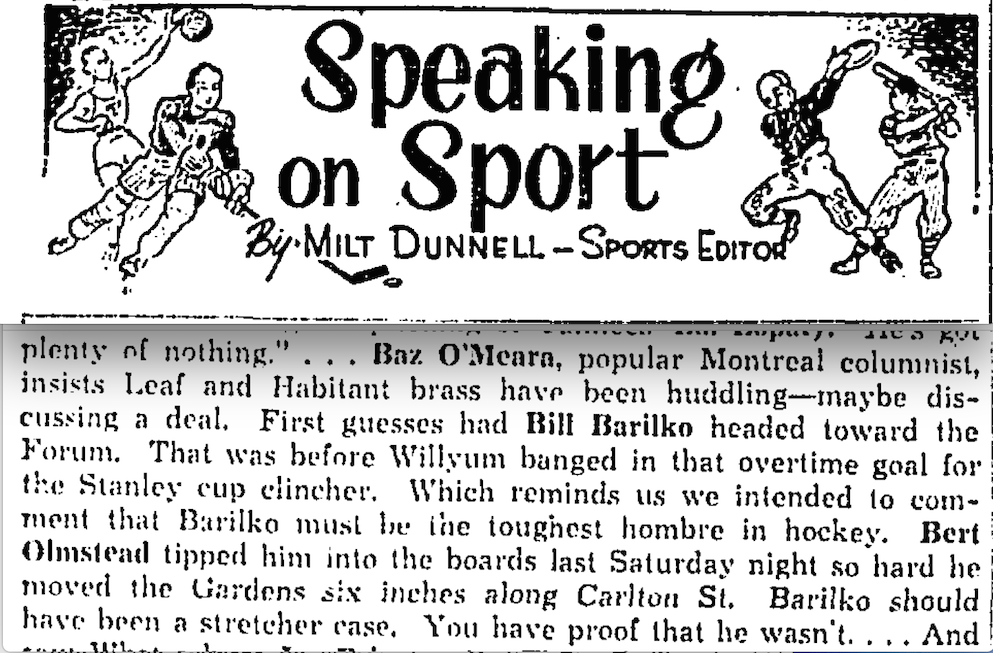

Scotty told Dave Stubbs that he had been a Bruins fan as a boy. That might seem strange for a child growing up in the Montreal borough of Verdun, but at the time, the Maroons had just recently folded and the Canadiens were struggling through what was then an unprecedented 13-year Stanley Cup drought from 1931 to 1944. The Bruins were a perennial powerhouse who won the Stanley Cup in 1939 and 1941. In his reply to me – which I share with you here – Mr. Bowman provides a little more detail:

Thanks Eric. As a 6-year-old, I started listening on radio to a strong Boston station I got in my home town of Verdun. A man named Frank Ryan did play by play. I stayed up for the 1st period and my Dad left a note for me to read before School with all the results. Somehow, I had Bill Cowley as my idol. My Mom worked at Eaton’s and she got me a Bruins sweater with Cowley’s #10 for Christmas one year. With World War II breaking out, they used to say about Cowley [a star center]: “HE MADE MORE WINGS THAN BOEING.”

Regards. Scotty

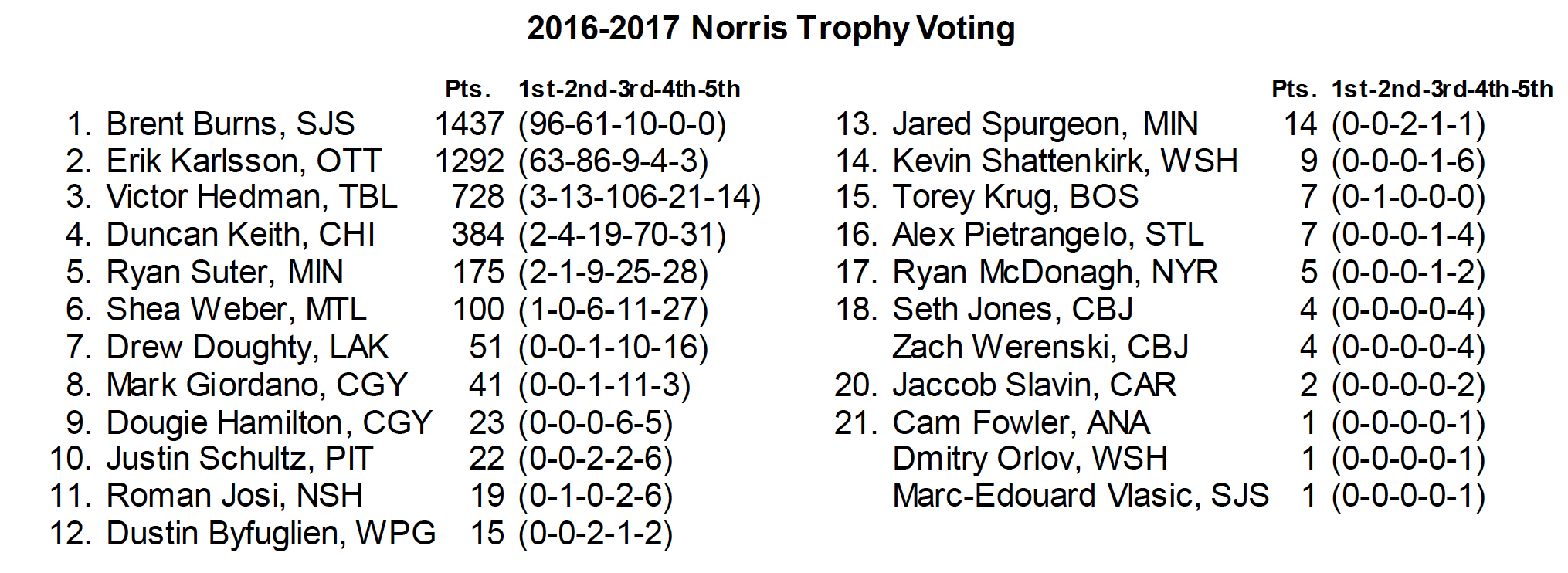

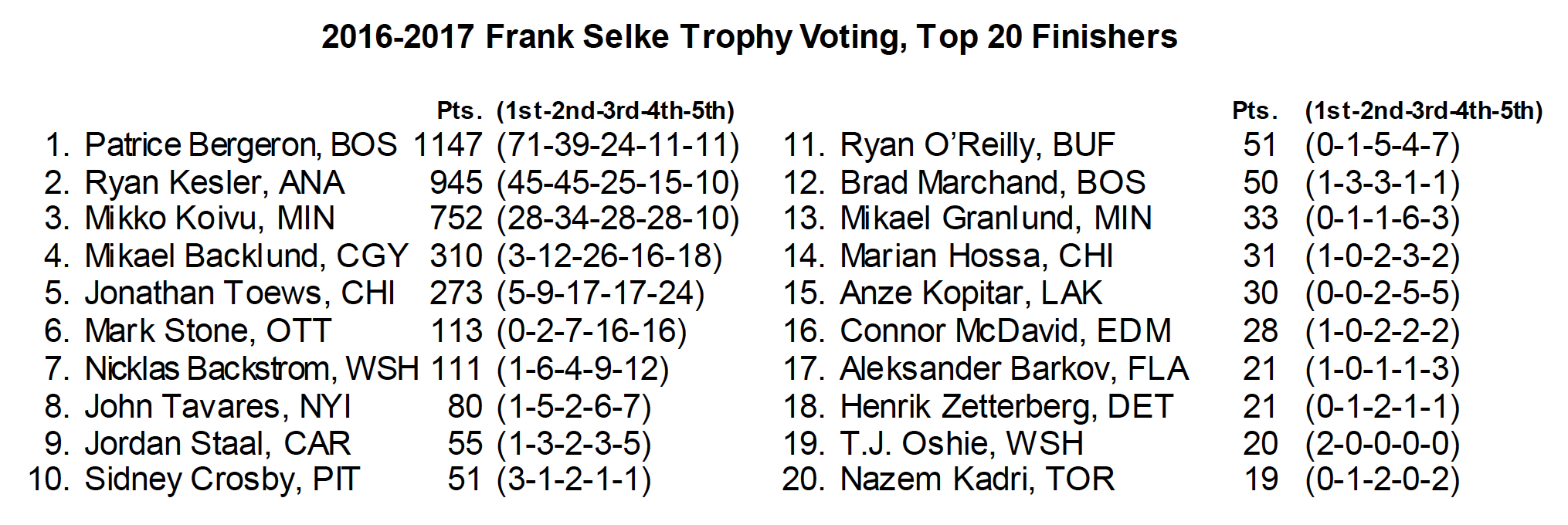

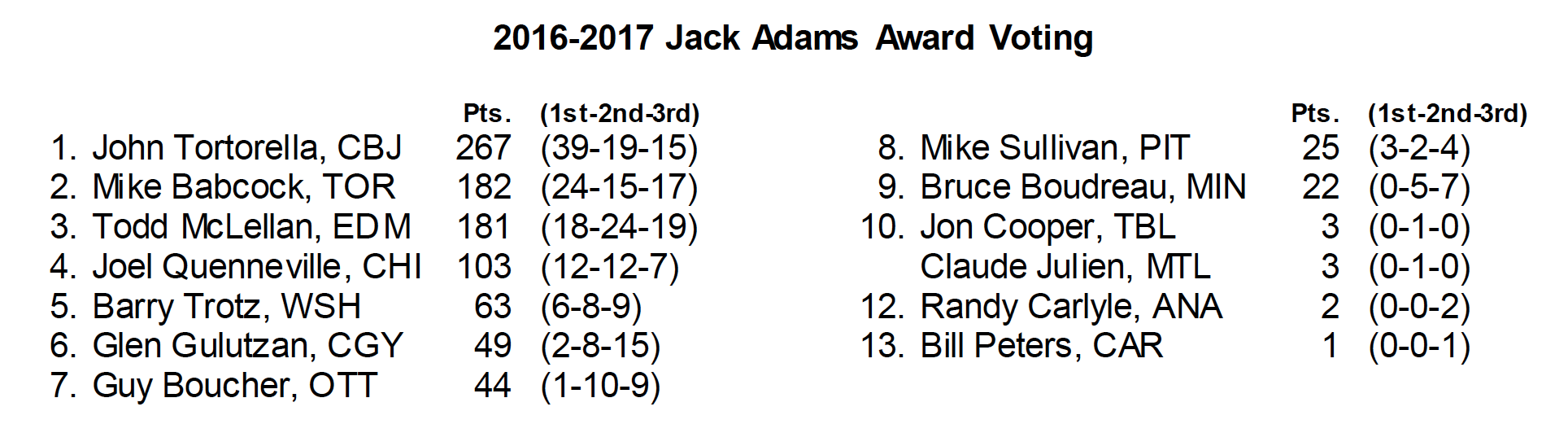

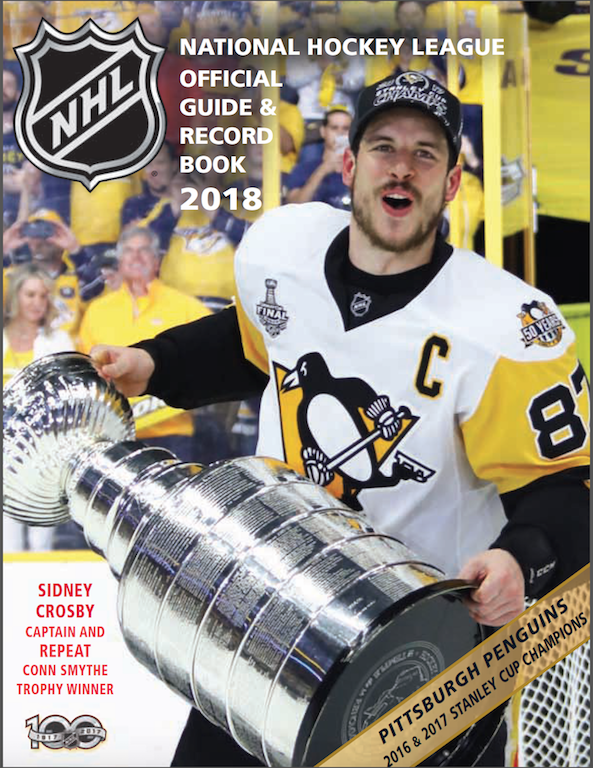

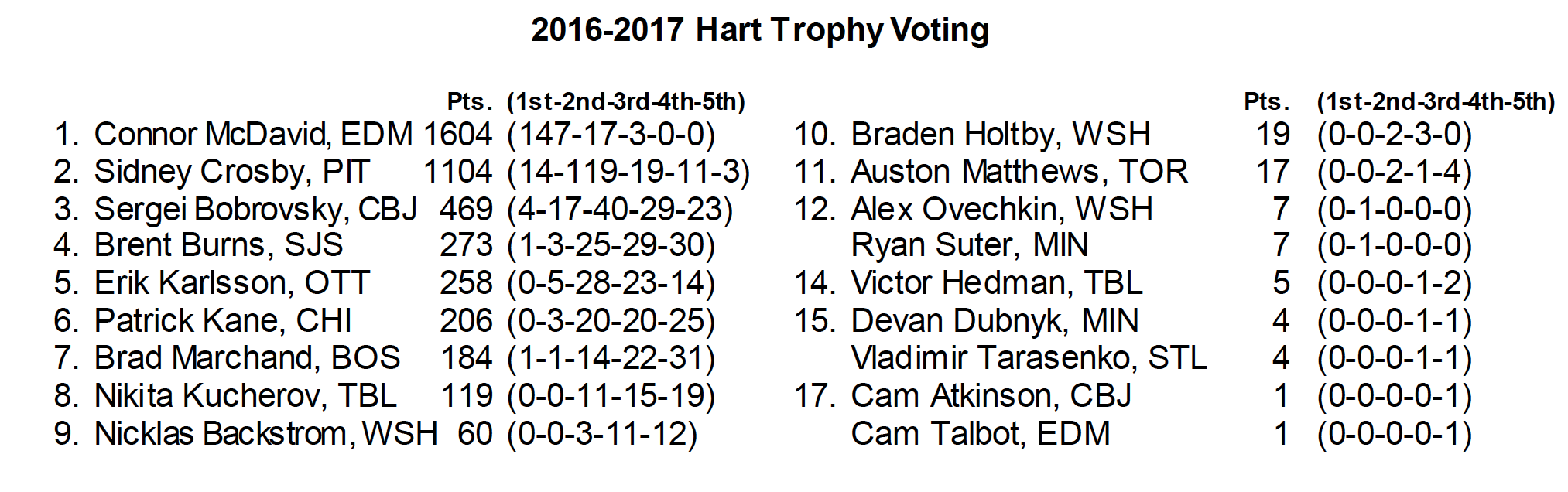

Selected from 167 votes cast by the Professional Hockey Writers Association.

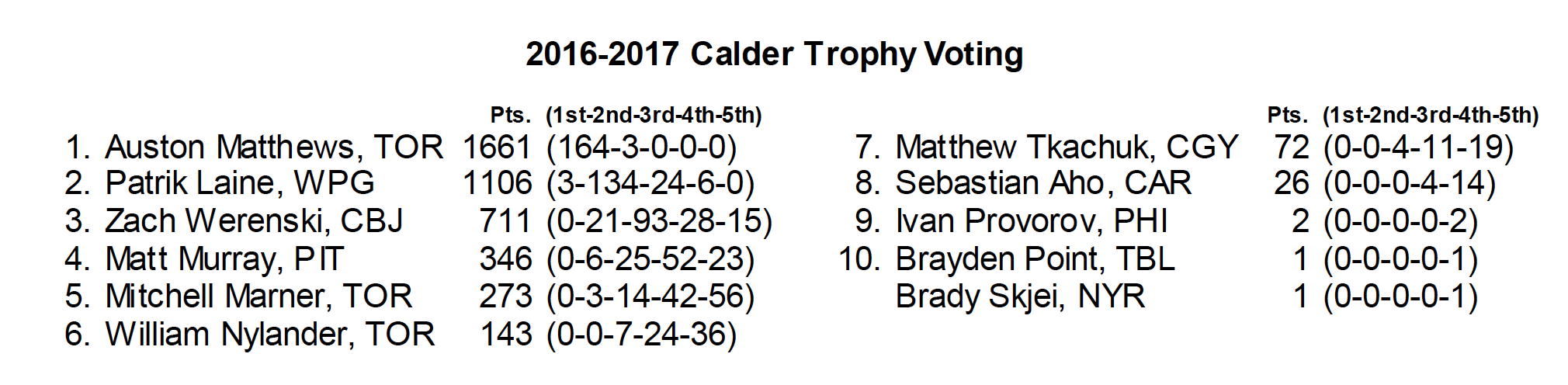

Selected from 167 votes cast by the Professional Hockey Writers Association.