Ninety-nine years ago today, on December 6, 1917, at 9:04 Atlantic Time (just about the time I’ve set this story to be published), the French ship Mont-Blanc, with a cargo of military explosives intended for the First World War, blew up in the harbour at Halifax shortly after colliding with the Norwegian vessel Imo. The explosion – often said to be the largest man-made blast until the Atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima – destroyed the community of Richmond in the north end of Halifx, leveling buildings, snapping trees, bending iron rails and shattering windows throughout the entire city of 50,000. In fact, the blast shattered windows 100 kilometers away in Truro, Nova Scotia, and could be heard in Prince Edward Island.

Close to 2,000 people were killed and another 9,000 injured. Some 25,000 people were left without adequate shelter. The Halifax Explosion resulted in $35 million in damages, which would be close to $600 million today. Rescue efforts began almost immediately – although they would be hampered by a blizzard that struck the next day. Supplies and money soon arrived from across Canada and the northeastern United States.

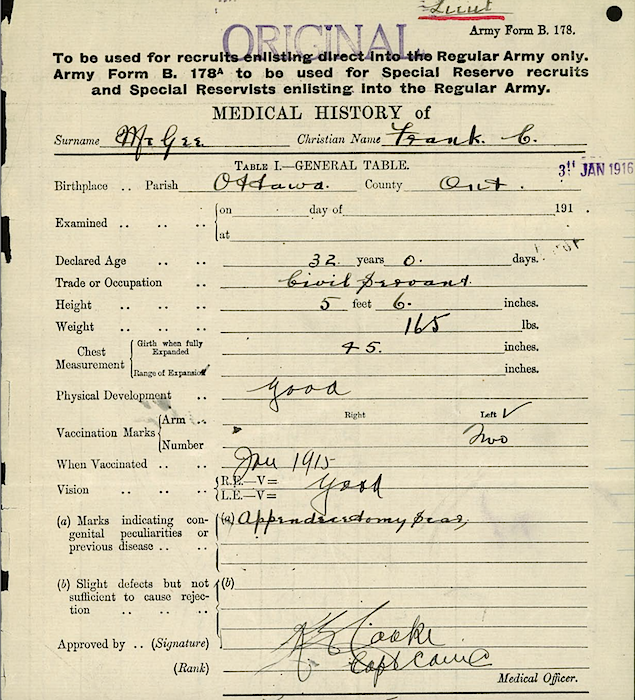

Newspaper accounts of the Halifax Explosion, December 6 & 7, 1917.

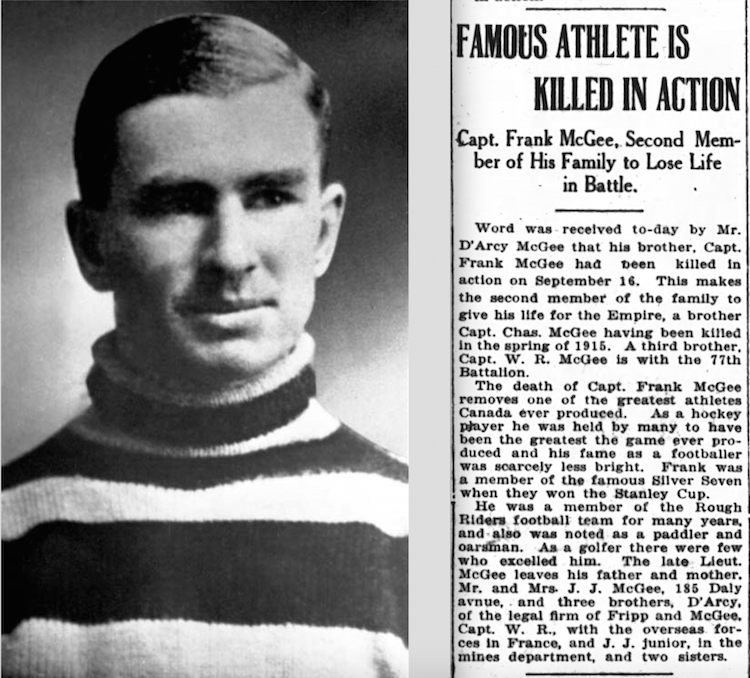

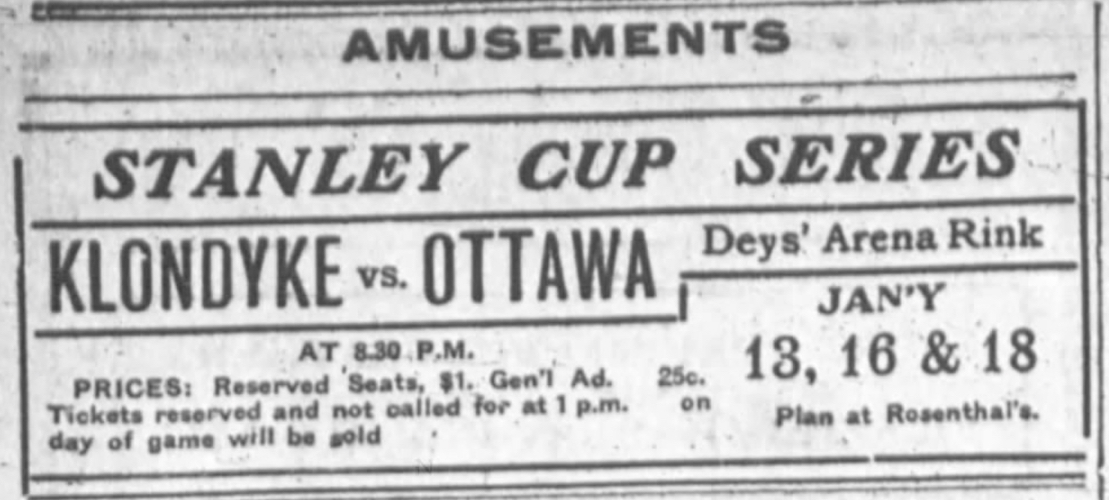

The hockey community did its part too. In Montreal the new season opened on Saturday, December 15, 1917, with a pair of fundraising games for the Halifax relief effort. The second of those games was little more than a glorified scrimmage, but was, in fact, the first game played in the history of the NHL – or, at least, the first game contested by players belonging to NHL teams.

I’m not the first to write about this – although I only know of two other sources. (One is the excellent 2002 book Deceptions and Doublecross by Morey Holzman and Joseph Nieforth about the formation of the NHL and the other is the web site Third String Goalie.) Neither says much about the game … but that’s likely because there was so little written about it at the time, and what there was is rather conflicting.

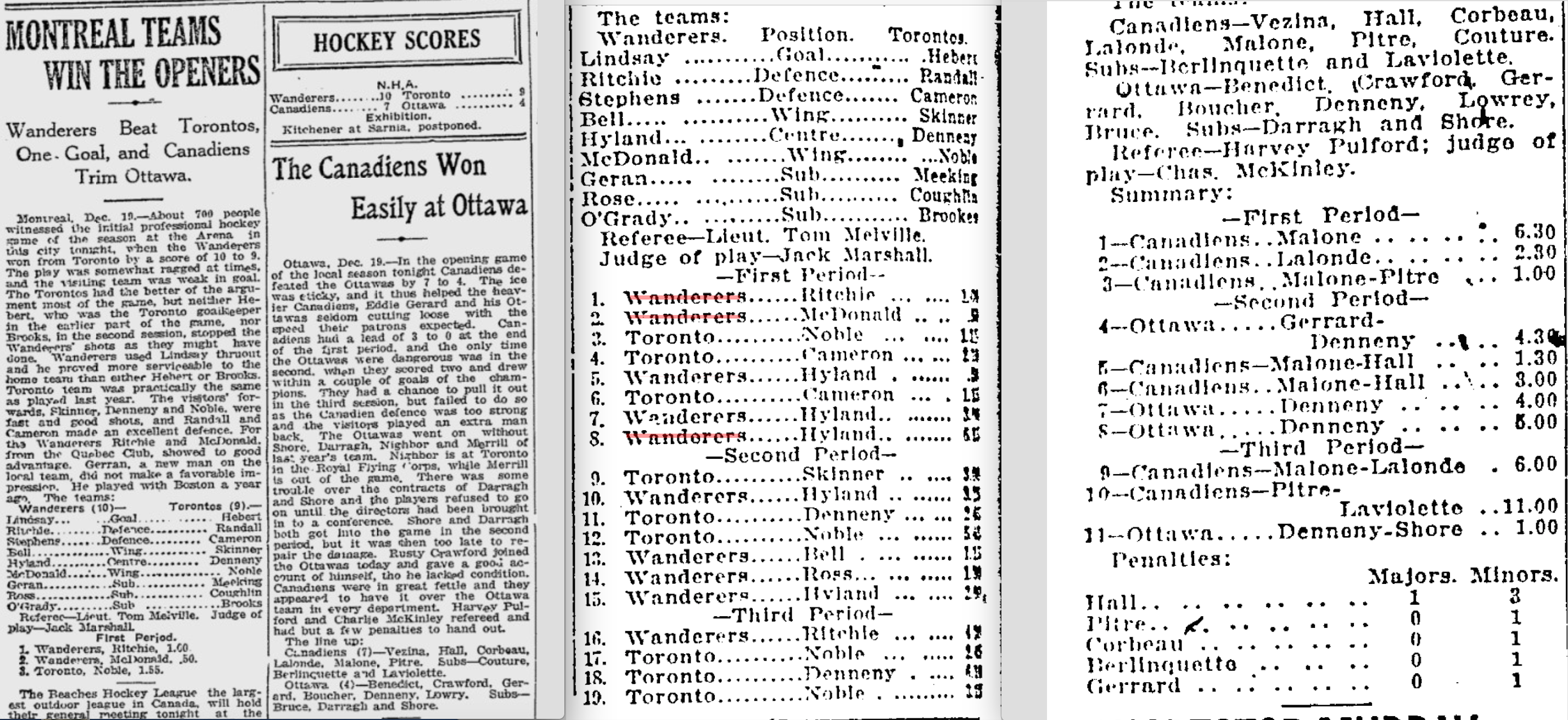

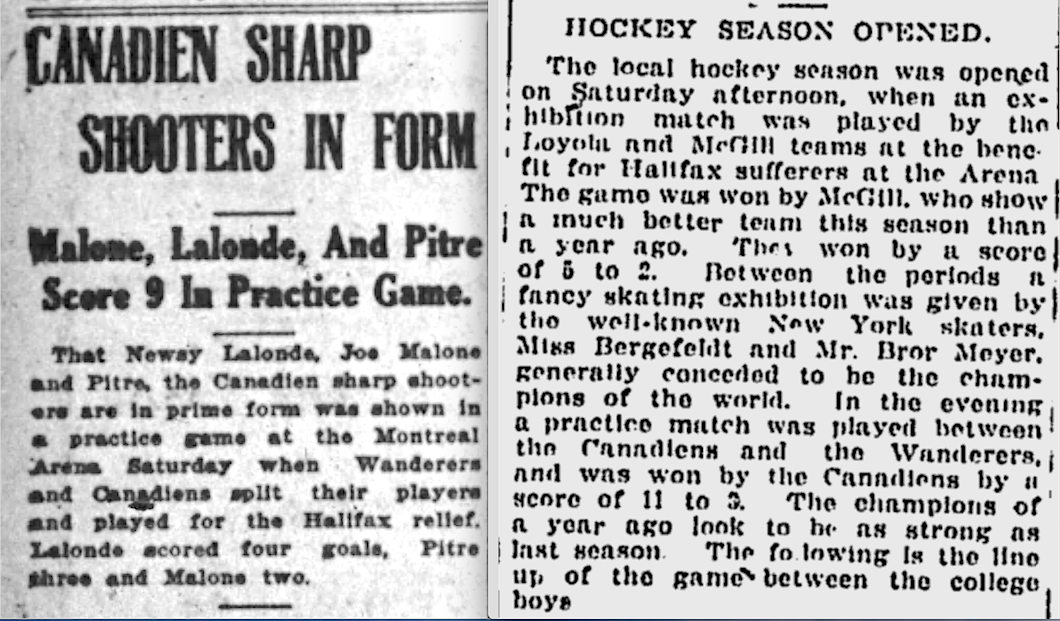

The NHL had been formed from the ashes of the recently defunct National Hockey Association in late November of 1917 and would officially open its schedule on December 19. This exhibition game on December 15 – despite what the Montreal Gazette says in the clip below – was played by mixed teams made up of players from the Montreal Wanderers and the Montreal Canadiens. The lineups in both the Gazette and the Montreal Star show the teams as follows:

Team 1 Team 2

- Bert Lindsay (W) G Georges Vezina (C)

- Jack Laviolette (C) D Joe Hall (C)

- Dave Ritchie (W) D Bert Corbeau (C)

- Joe Malone (C) F Harry Hyland (W)

- Newsy Lalonde (C) F Jack McDonald (W)

- Didier Pitre (C) F Billy Bell (W)

- Louis Berlinguette (C) Sub Billy Coutu (C)

- Phil Stephens (W) Sub George O’Grady (W)

Brief coverage of the game in the Ottawa Journal

(December 18) and Montreal Gazette (December 17).

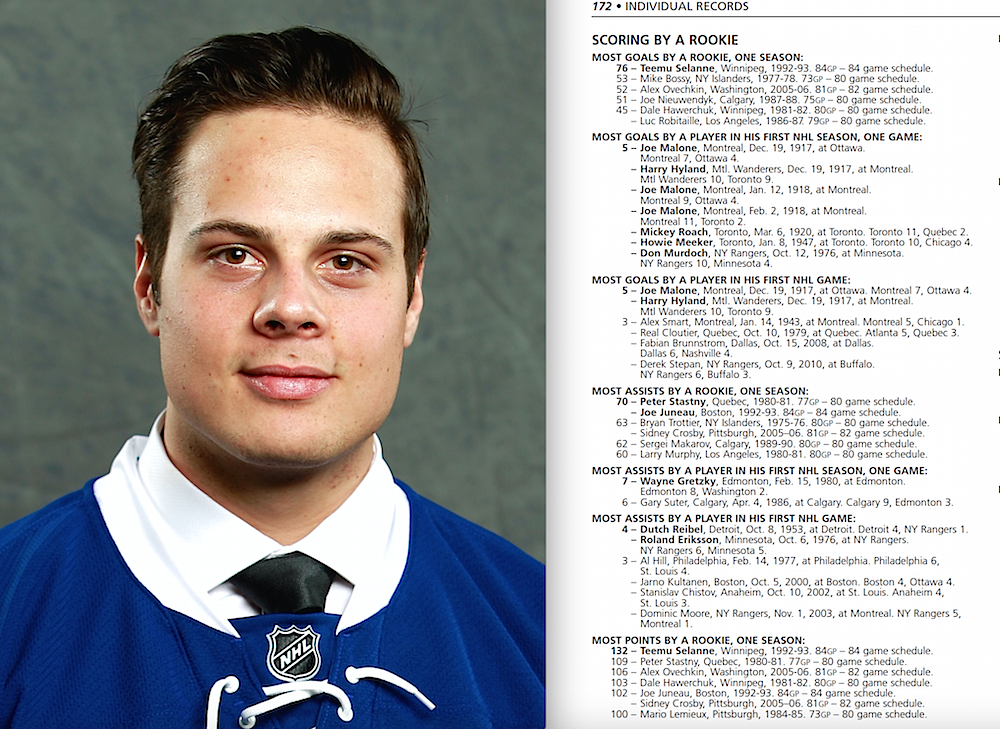

Team 1 was the winner, but different sources list the score as 11-3, 10-3, and 10-2. The Montreal Star has it as 10-3 and reports the scorers as Lalonde (4), Pitre (3), Malone (2) and Berlinguette for the winners with Hyland scoring all three for the losers.

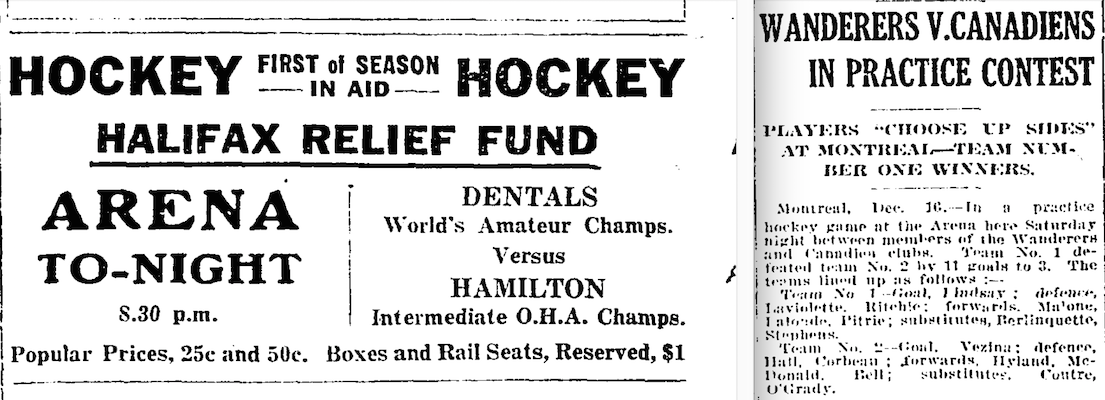

One night before the games in Montreal, the senior amateur season of the Ontario Hockey Association kicked off in Toronto on Friday, December 14 with its own exhibition for the Halifax Relief Fund. The defending Allan Cup champion Dentals Hockey Club of Toronto (and, yes, they were all either dental students or recent graduates of the dental program affiliated with the University of Toronto) defeated the Hamilton Tigers 5-4.

Toronto’s Globe newspaper ran an ad for the local benefit game on December 14

and had a brief summary of the game in Montreal on December 17.

Though it was advertised as a fundraiser (and said afterwards to have been a very entertaining game), only 1,200 fans showed up. No account seems to give the attendance for the games in Montreal, and nothing I’ve come across indicates how much money was actually raised in either city for the victims in Halifax.

[NOTE: I was later sent a story about the Montreal game in the French-language Le Devoir newspaper that stated “Huit cents personnes environ” – about 800 persons – attended. This newspaper also has the score 10-3, but again, no mention is made of how much money was raised. Thank you Daniel Doyon.]