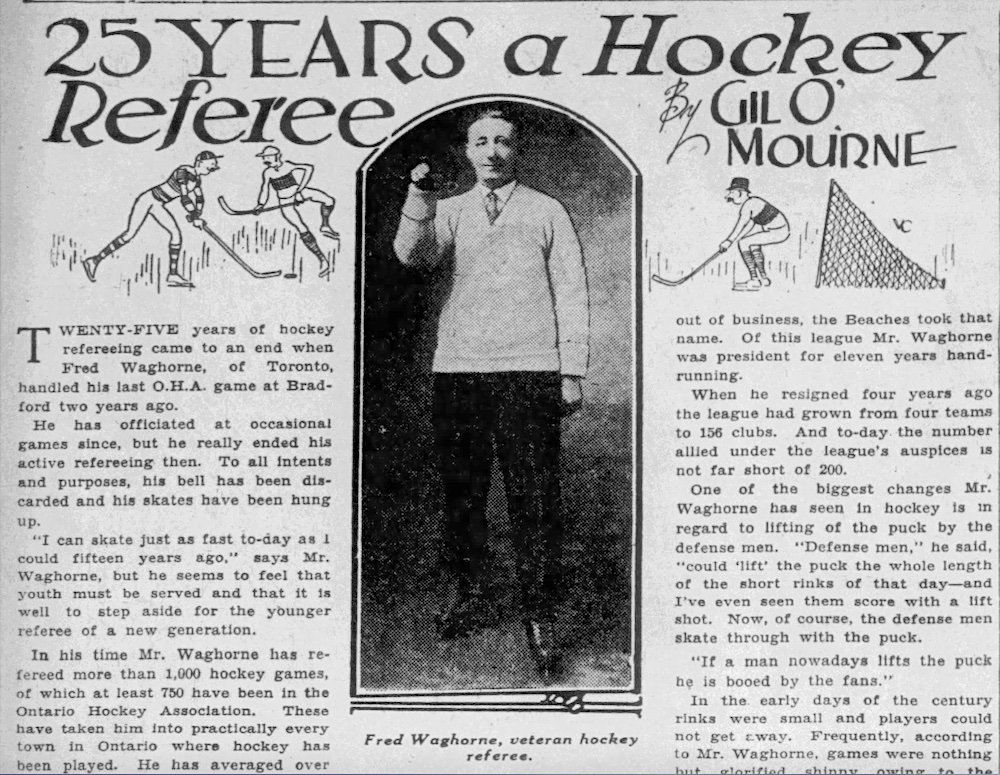

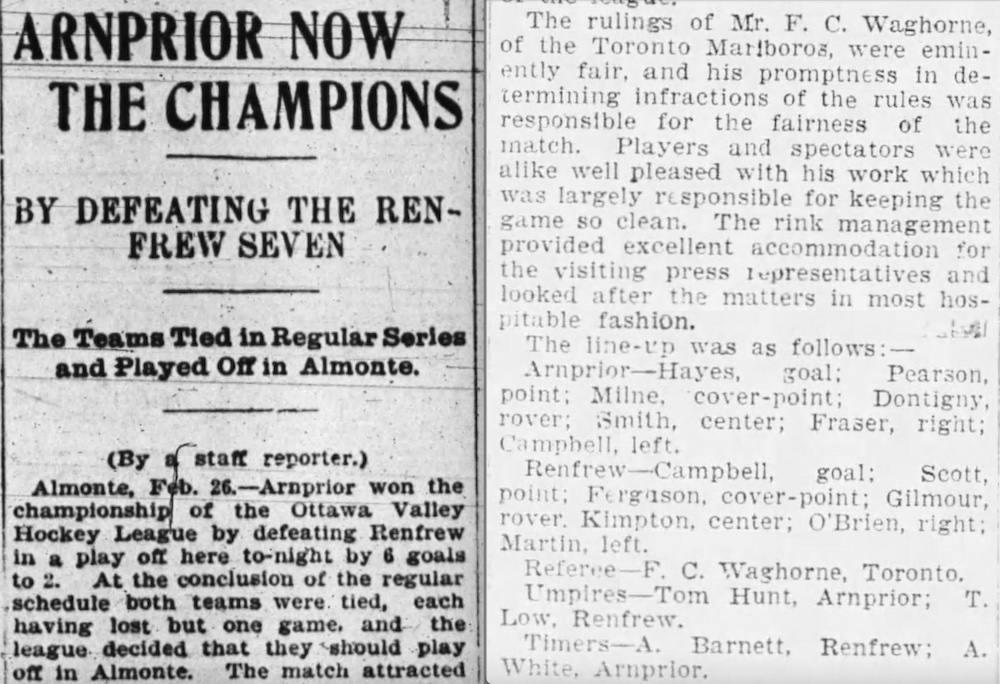

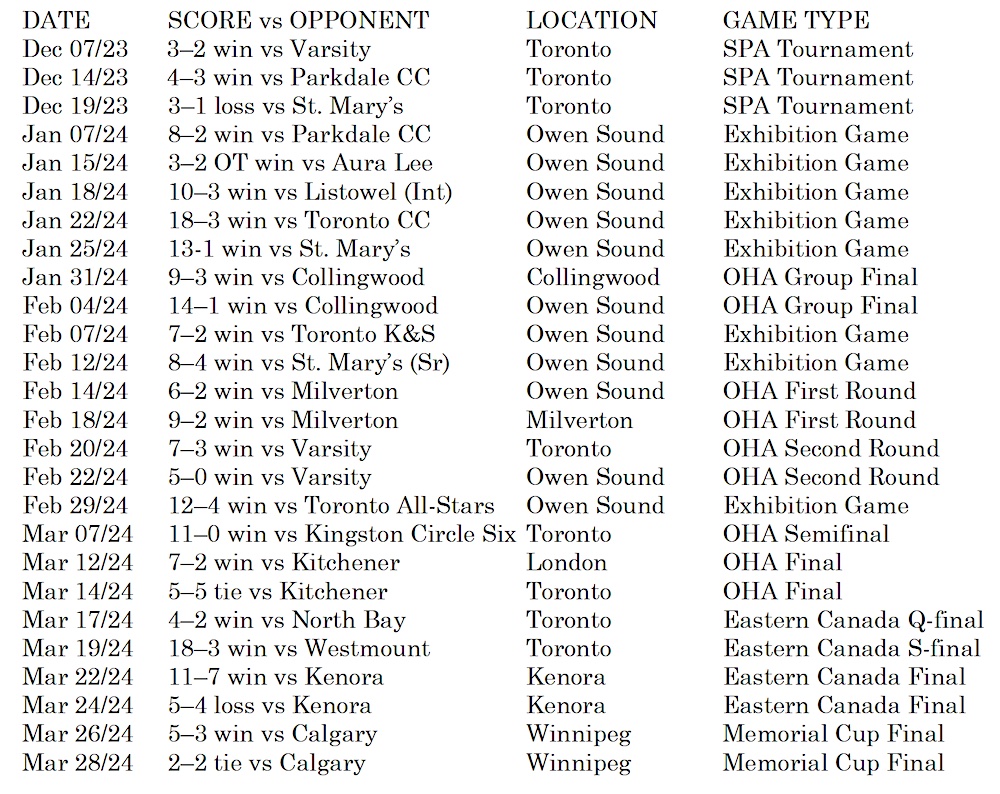

I’ve lived in Owen Sound since the fall of 2006. Admittedly, I haven’t been a very good fan of the Owen Sound Attack. Still, the history of hockey here has a hold on me. With a population of just over 20,000 people, Owen Sound is by far the smallest market in the Ontario Hockey League, and is third-smallest in the Canadian Hockey League behind Swift Current in the Western Hockey League (circa 18,000) and Acadia-Bathurst (circa 13,000) in the Quebec Maritime Junior Hockey League. One hundred years ago this month, in March of 1924, the Owen Sound Greys became the first small-town team to win the Memorial Cup. In 1927, the Greys became the first team from a city of any size to win the Memorial Cup twice.

Emblematic of the junior championship of Canada, the Memorial Cup was established in 1919 to honour those who died in service to Canada during World War I. First won by the University of Toronto Schools team, it was won by three different Winnipeg teams in three of the next four years. Fort William won the Memorial Cup in 1922, but with a population of about 36,000 (that may actually include Port Arthur too), the city was roughly three times as large as Owen Sound, which had a population of only 12,000 people in 1924.

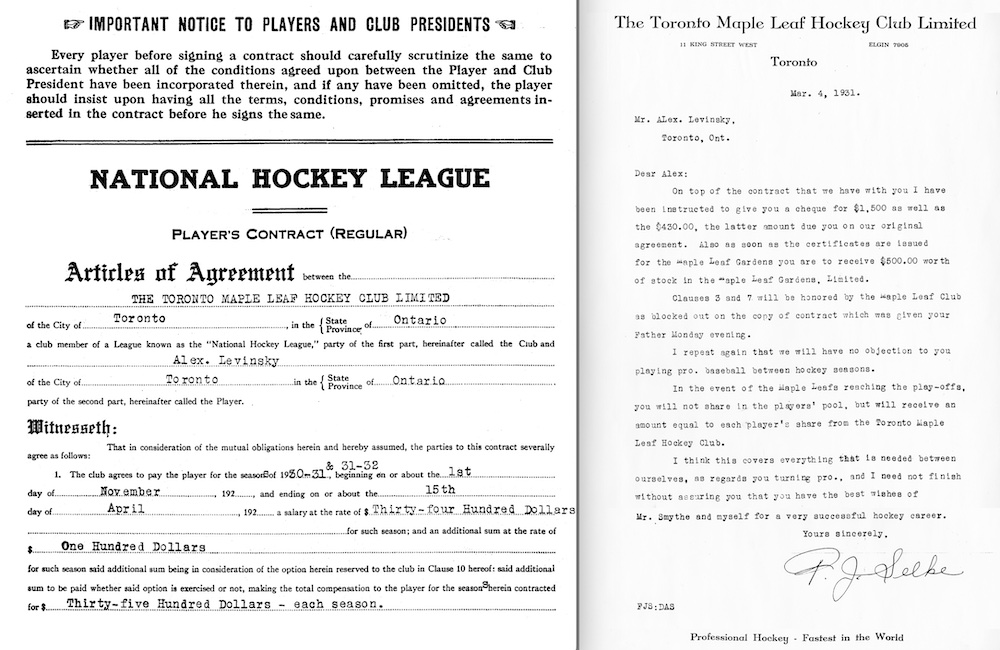

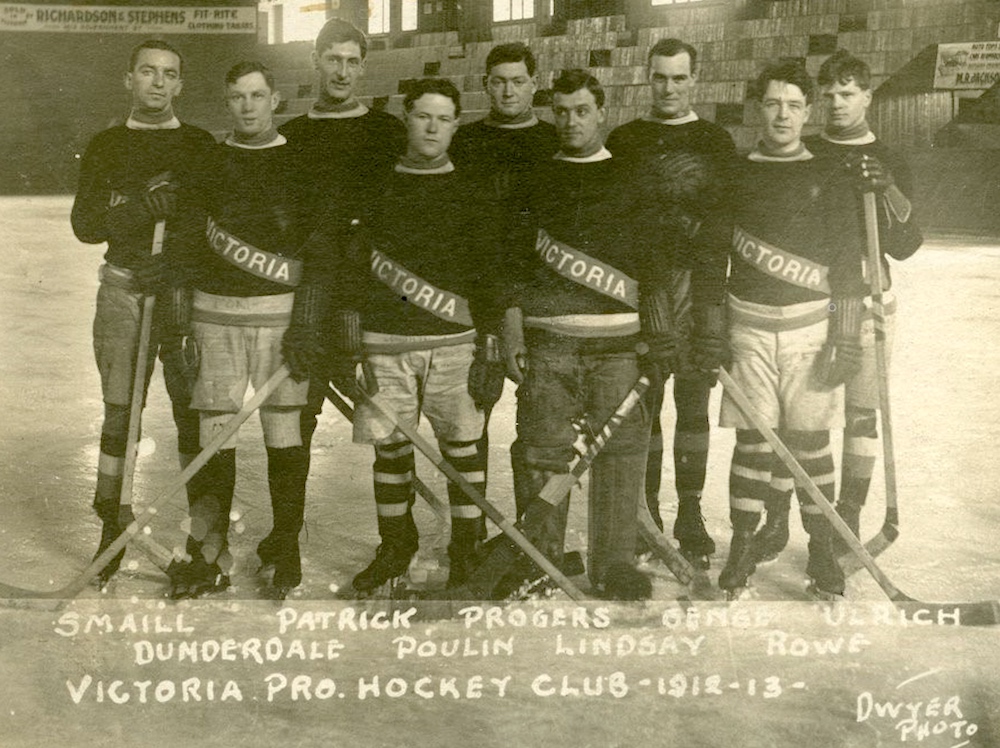

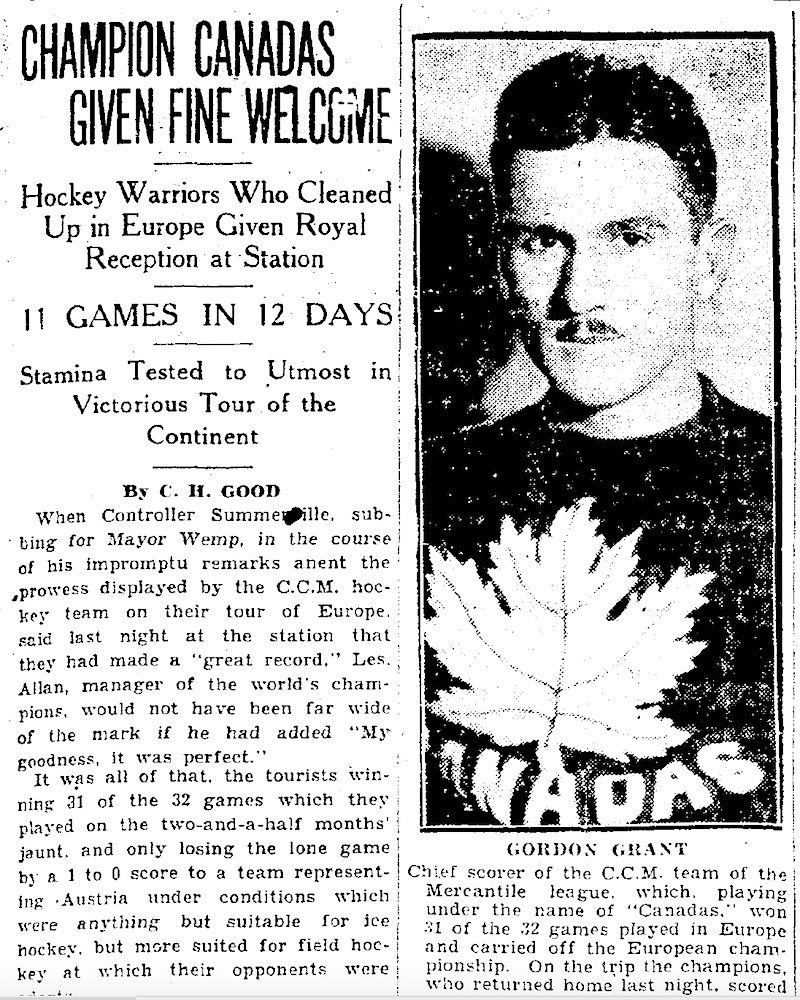

E.N. “Jimmie” Jameson (manager) Fred Elliott. Middle: Teddy Graham, Larry Cain,

Elgin Wright. Seated: Cooney Weiland, Hedley Smith, Bev Flarity.

(Photograph courtesy of Ron Burrell.)

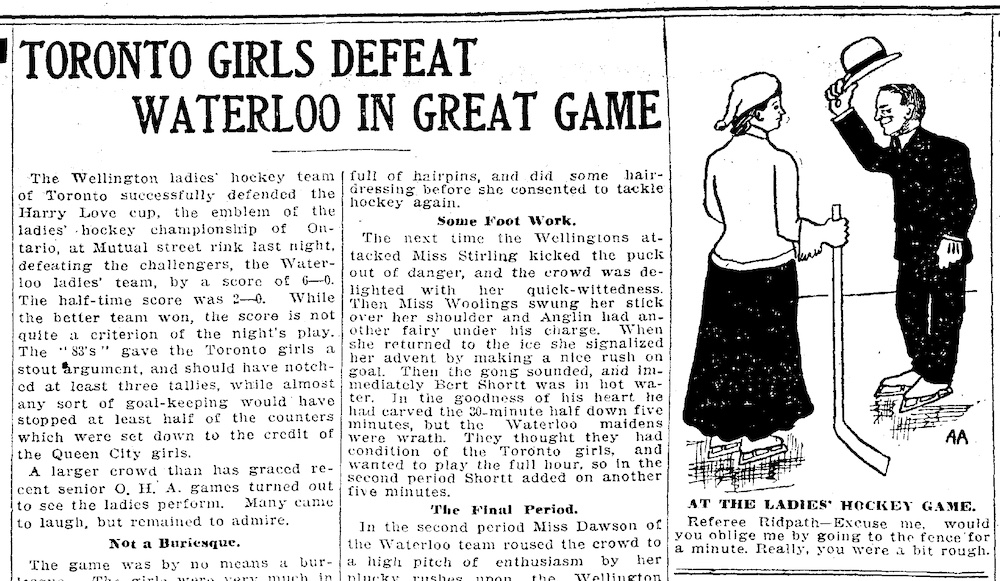

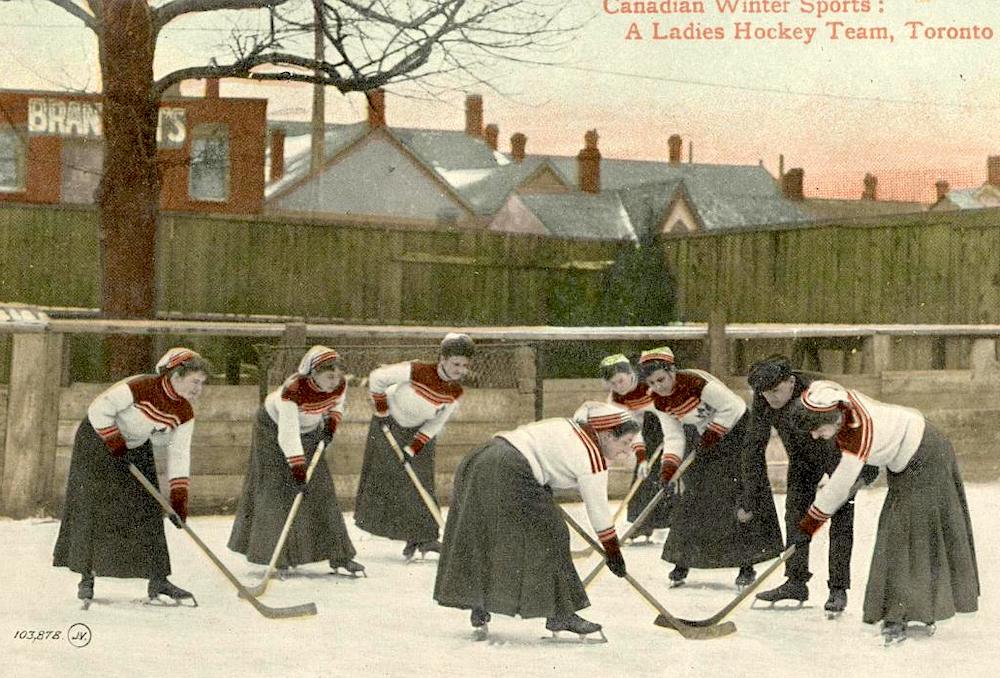

Hockey in Owen Sound is thought to date back to the 1880s. According to research by Paul White, the first formal game here was played by a team of local bankers circa 1888. An indoor skating rink opened in Owen Sound in January of 1893, which proved to been a big boon to hockey in the city, but there had already been a “town” team to take on the bankers by 1892. On December 6, 1897, The Globe newspaper in Toronto wrote of a league being formed with Owen Sound, Shelburne, Markdale, and Dundalk. On December 12, 1898, The Globe reported that the Owen Sound Collegiate (high school) hockey team had been reorganized, indicating that there had already been a high school team previously. On February 8, 1900, The Globe reported on a game to be played that night between the Owen Sound and Orangeville Ladies Hockey clubs.

The Owen Sound Greys (or Grays as they were known in early days) was a name given to the town’s junior hockey team around 1912 or 1913. It seems the name had less to do with the fact that Owen Sound is the county seat of Grey County and more with the fact that Bill Hancock — a referee and tailor working in town — was asked to coach the team and outfitted them in grey sweaters and socks with a red band.

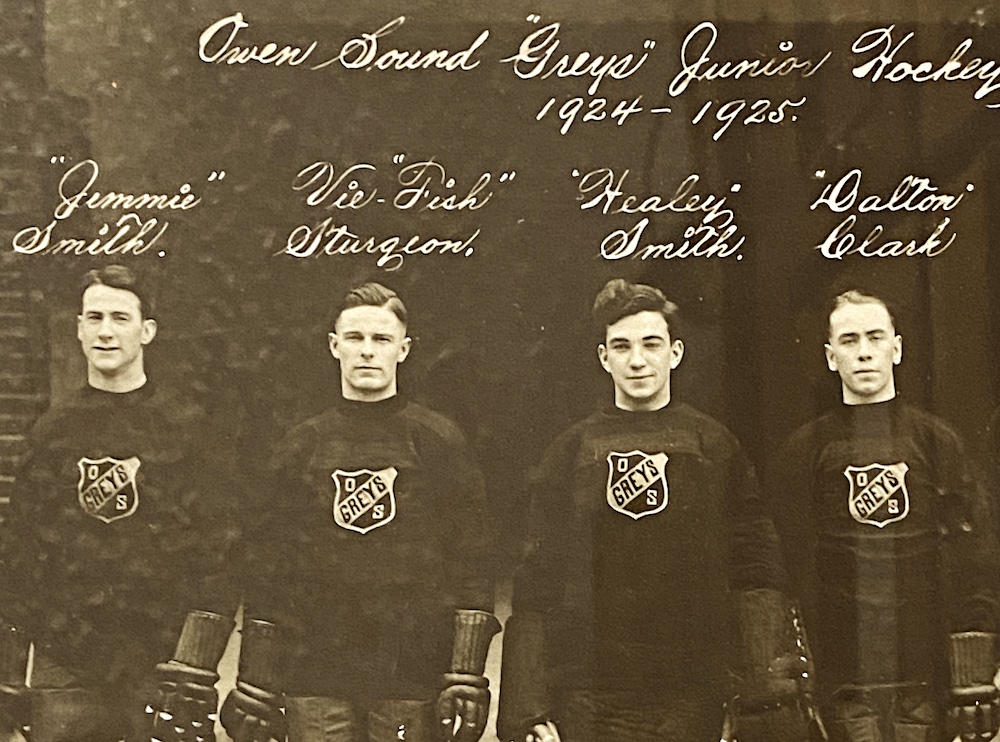

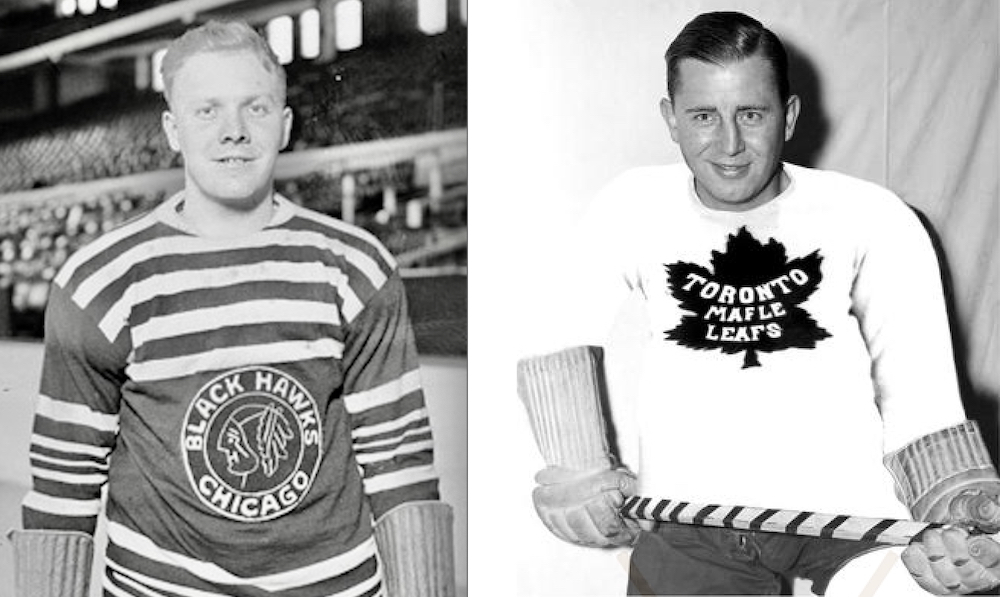

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 slowed down the advancement of junior hockey in Owen Sound, but the Greys were back and ready to flourish in the 1920s. By the 1923–24 season, the Greys featured homegrown stars and future NHLers Melvin “Butch” Keeling (his father was a butcher) and Teddy Graham. Though they were only 18 and 19 years old that season, they were both said to be in their fourth year with the team.

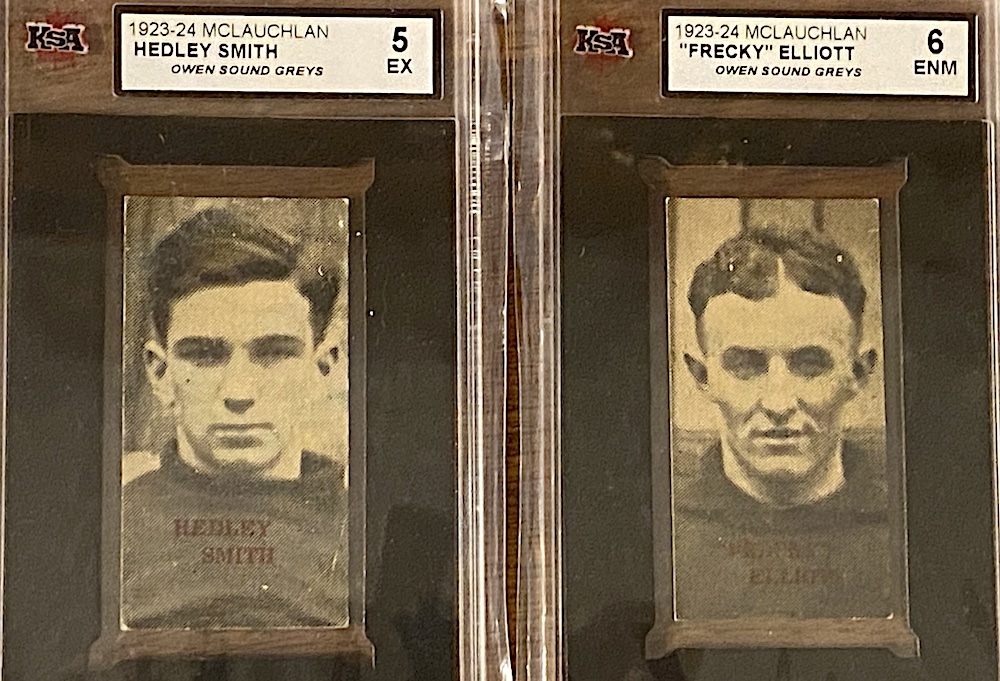

Another local star was goalie Hedley Smith, who moved from Toronto to Owen Sound around 1917. He was just 16 years old in 1923–24, and in his first full year with the Greys after having played for them briefly the year before while starring for the Owen Sound Collegiate Institute high school team. Keeling, Smith, and Graham (who were all still attending OSCI) grew up within a few blocks of each other on 4th Avenue West in Owen Sound, and had attended the Victoria School (which was also on the same street). All were coached by Henry Kelso, for whom Kelso beach in Owen Sound is named, and who also lived on 4th Avenue West! Victoria School was a local powerhouse, and Smith was said to have won four straight hockey championships there before moving on to high school.

For the 1923–24 season, the Greys added Larry Cain from Newmarket, Ontario and Fred “Frecky” Elliott (AKA George) of Clinton, Ontario. Still, the key out-of-town recruit had come the year before when Ralph “Cooney” Weiland of Egmondville joined the team in 1922–23 after four seasons playing near home in Seaforth, Ontario. Weiland was only 17 that season, but came to Owen Sound to finish high school and apprentice as a drug clerk in a local pharmacy. A star center who addition to the team caused Butch Keeling to move to left wing, Weiland has traditionally been credited with 68 goals in 25 games for the Greys in 1923–24 (the Society for International Hockey Research has him with 70 goals in just 24 games) while Keeling had 62 in all 26 games. (SIHR shows him with “only” 61 goals in those 26 games.)

The story of the 1924 Memorial Cup championship begins on October 29, 1923, at the Arcadia Dance Hall — “over Owen Sound Garage” — and to the music of the Bon Ton Orchestra. A story in the Owen Sound Sun-Times on October 23 reports it was hoped that 500 tickets would be sold for the benefit dance. An account of the evening in the October 30 paper notes only 200 attendees but says “the hall was filled with a merry throng of dancers who tripped the light fantastic…” The evening was called “a splendid success,” and it was said that “[t]he net proceeds of the Dance will considerably augment the funds of the Hockey Club.”

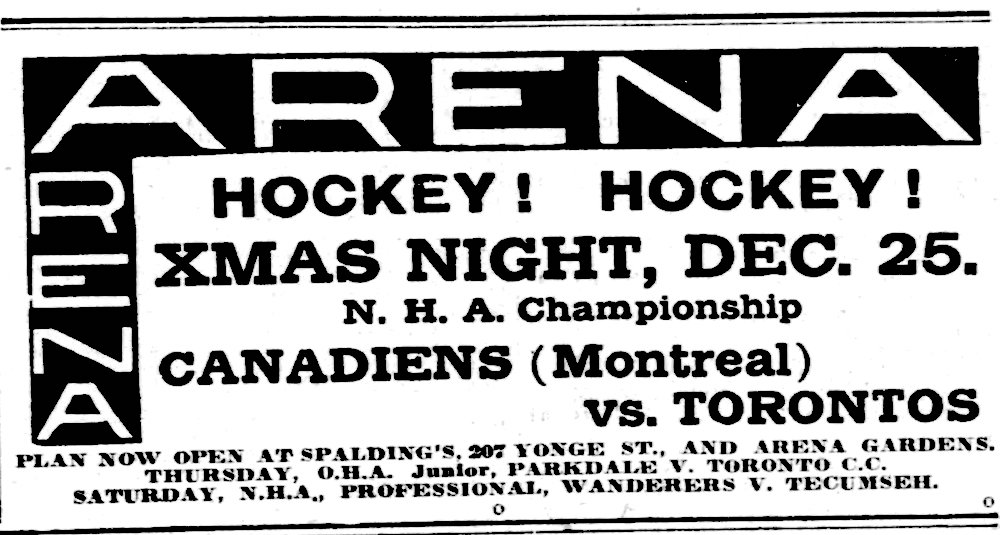

Hockey training got started a little over two weeks later on November 15, when most of the team was present for a workout at the local YMCA. Road work (jogging?) commenced on November 19. It was already known that the Greys would kick off the season in Toronto in early December as part of the annual Sportsman’s Patriotic Association (SPA) tournament at the Mutual Street Arena, but there would be no ice available in Owen Sound’s Riverside Arena (a natural ice facility that required cold weather) until later in December.

The Greys wouldn’t actually hold their first practice until they arrived in Toronto and got onto the artificial ice surface there two days ahead of their opening game on December 7, 1923. Even so, they scored a 3–2 win over Conn Smythe’s University of Toronto Varsity juniors that night and Canadian Press reports noted their already being a favourite to win the Ontario Hockey Association title. But after a 4–3 win over the Parkdale Canoe Club a week later, the Greys lost the SPA championship to St. Mary’s in a 3–1 defeat on December 19. That same Toronto team had knocked out the Greys in the OHA playoffs the previous season, but this loss would prove only a minor setback.

of the losses came in the second game of total-goals series

where the team had already put up a victory in the first game

The OHA had 64 junior teams playing in 18 regional groups for the 1923–24 season. (Some records show 20 groups, but a few were combined from two groups to one.) Owen Sound was in Group 16 with Collingwood, Meaford, and Stayner. However, while those three cities play the others two times each at home and two on the road for a four-game Section A “regular season,” the Greys (who were much further west) were placed alone in Section B. Throughout the month of January, while Collingwood, Meaford, and Stayner played each other, Owen Sound stayed home. The Greys hosted four Toronto junior teams and an intermediate squad from Listowel in five games they won in mostly lopsided romps. After Collingwood won all four OHA games they played, the Greys met the Shipbuilders in a two-game, total-goals Group 16 final to decide which team would advance to the provincial playoffs.

Game one of the Group 16 final took place in Collingwood on January 31, 1924. It was the first time the Greys had played on the road since the SPA final in mid December. The Shipbuilders got off to a fast start, firing several shots at Hedley Smith, who stopped them all. Cooney Weiland put the Greys on top midway through the period, and it was all Owen Sound after that. Weiland with three, Fred Elliott with three, and Butch Keeling with two led the way to a 9–3 victory. Collingwood was unable to field a full team for the return match in Owen Sound on February 4, so the Shipbuilders added a few intermediate players. This forced them to default, although the game was played anyway … and the Greys scored a crushing 14–1 victory with Weiland scoring four this time, Elliott three, and Keeling two.

Attack are featuring this season. (Photograph Courtesy of Ron Burrell.)

Two more lopsided exhibition wins followed, before the Greys met Milverton in the first round of the OHA provincial playoffs. When Milverton led 2–1 after the first period of the series opener on February 14, it was the first time Owen Sound had trailed anyone after one period but the hometown Greys recovered for a 6–2 win. Four nights later in Milverton, it was a 9–2 victory to take the series by a combined score of 15–4. Next came two more one-sided playoff wins against the Varsity Juniors, followed by a bye through the quarterfinals and a direct spot in the OHA semifinals.

With no games on their schedule for two weeks after defeating Varsity, an exhibition was arranged at the Riverside Arena against a picked team of Toronto All-Stars on February 29. A 12–4 victory that night marked the Greys last game on home ice this season, but there was still plenty more hockey to play.

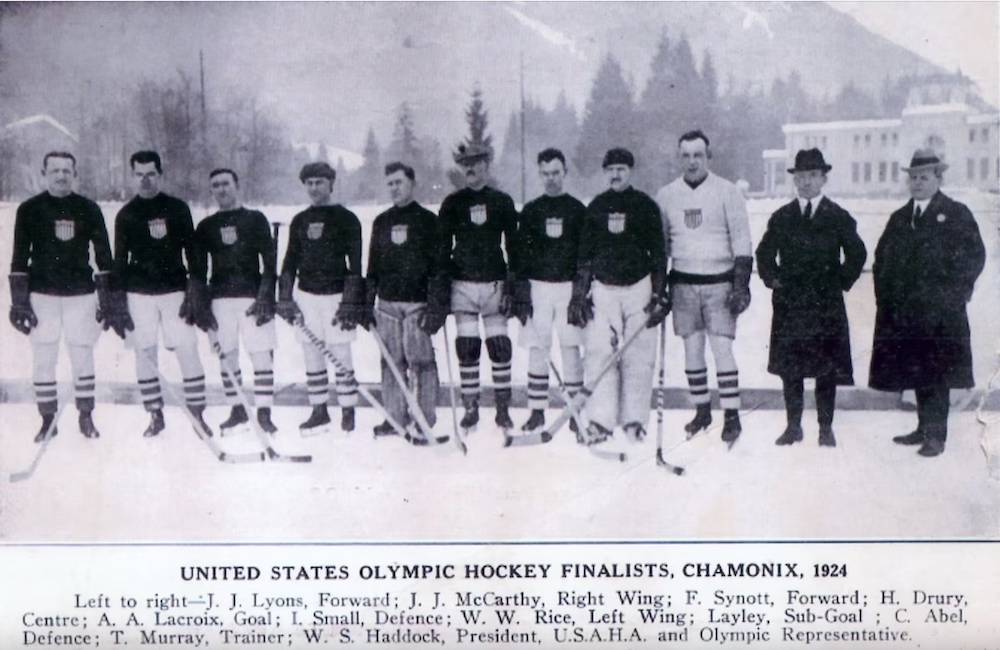

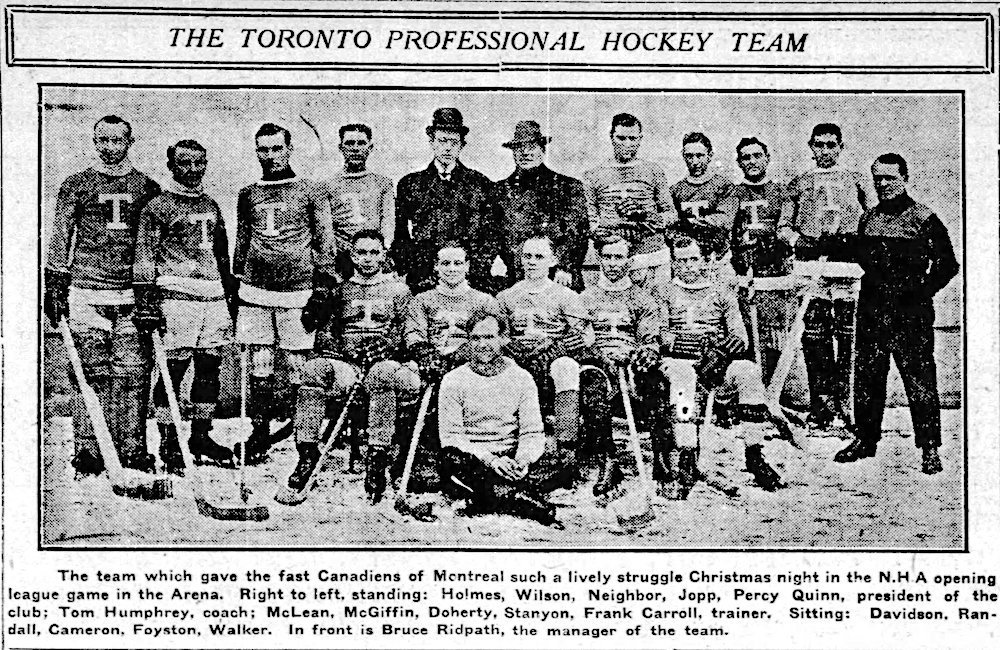

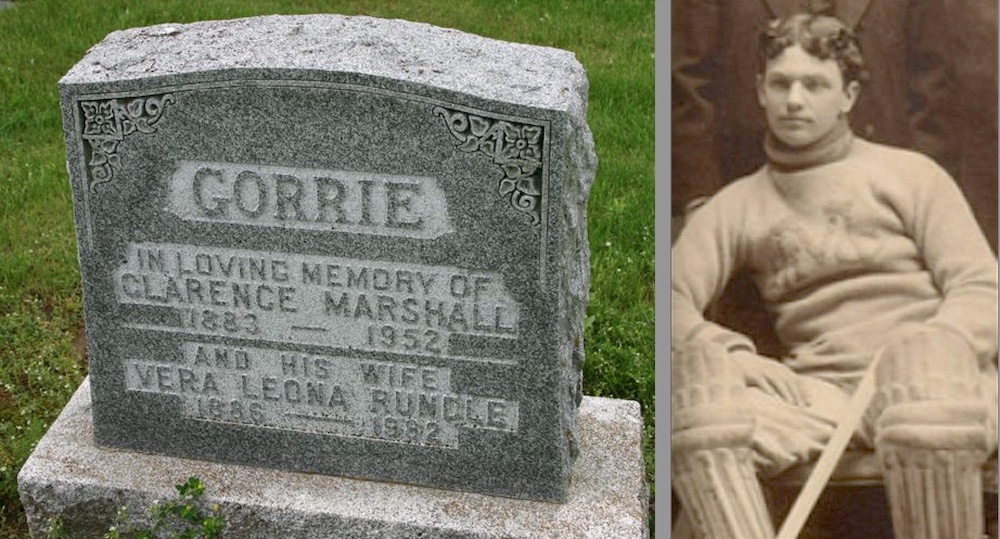

(Photos from the Society for International Hockey Research.)

The team traveled to Toronto for a sudden death OHA semifinal against the Kingston Circle Six on March 7 and won it 11–0. The Circle Six were said to be one of the hardest checking teams in junior hockey, but Owen Sound’s speed and clever “combination play” (passing game) carried the day. Keeling scored six times, including three in the third period when Weiland added two to the goal he’d scored earlier for yet another hat trick.

Next up was the OHA Final against the Kitchener Greenshirts, with Kitchener playing their home game 100 years ago tonight, on March 12, 1924, in London on the new artificial ice rink there because of warm weather at home. For the same reason, Owen Sound arranged for their “home” game two nights later to be played in Toronto.

After a 7–2 win in game one, the London Free Press said: “The Owen Sound Greys proved beyond a shadow of a doubt that 1924 is their championship year…. A big crowd of fans witnessed what was a revelation to many. Speed and plenty of it carried the Greys from the North all over their opponents.” The London paper praised the forward line of Weiland, Keeling, and Elliott, calling them “a wonderful scoring machine.” The Toronto Mail and Empire was particularly impressed by the work of the two wingers. “Keeling was undoubtably the star of the game … [while] Elliott also shot wonderfully well.” Still, it was Weiland who led all scorers with another hat trick. He “played his position perfectly, but that also goes for the rest of the players…. Larry Cain and [Teddy] Graham played very steady hockey on the defense and their speed on the attack dazzled the Kitchener kids.”

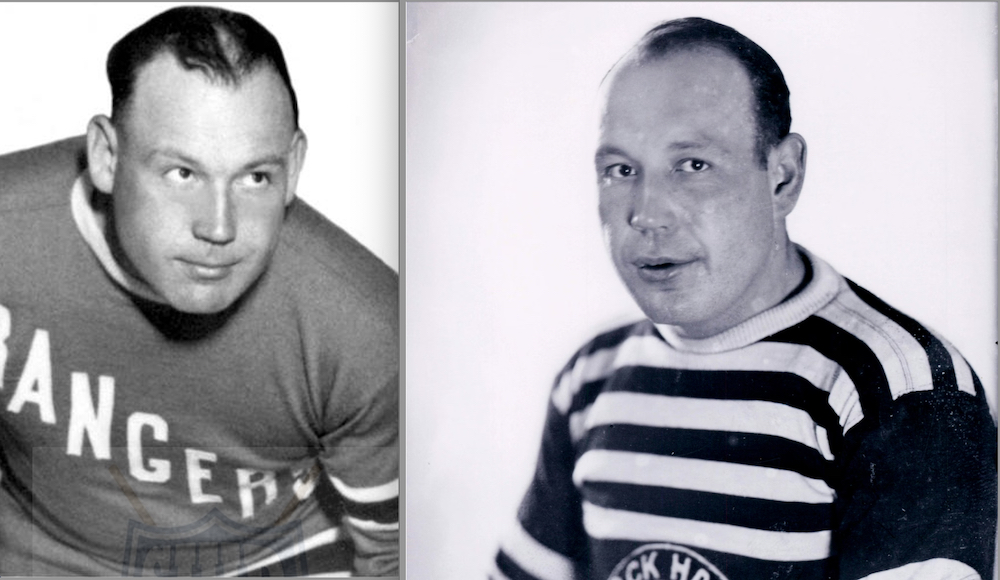

helping the Greys win the Memorial Cup again in 1927. He chose to pursue his

education instead. Fred Elliott played in the NHL with Ottawa in 1928–29 as

part of a four year pro career. (Photos courtesy of Ron Burrell.)

Game two in Toronto on March 14, 1924 was something of a shock. Kitchener led Owen Sound 5–2 after two periods to pull within two goals in the total-goal series. “There was real anxiety in the Owen Sound camp,” reported the Sun-Times, “… [but] it was in the last frame that the class, the condition, and the machine-like training of the Owen Sound boys shone out again.”

Goals from Weiland, Graham and Weiland again (along with Elliott’s first-period marker, and Keeling’s in the second) salvaged a 5–5 tie and gave the Greys a 12–7 win overall. There was some disappointment that after running up 16 wins in a row, the tie apparently left the team one win short of the OHA record of 17 consecutive wins held by the New Hamburg intermediates. Still, the Greys had earned the first OHA championship in Owen Sound history.

Next time, we’ll follow the OHA champion Greys through the Memorial Cup playoffs of 100 years ago and see how Owen Sound celebrated the national title.