I’ve never really been one of those Jewish sports fans who cares a whole lot if a player is Jewish. But I do love trying hunt down the facts. So, when my brother texted “Way to go Jewish (I suppose) hammer thrower!” and I texted back, “Hadn’t thought of that” I quickly got on the case.

Ethan Katzberg certainly sounds like a Jewish name – and Katzberg himself looks like he could be Jewish – but it was hard to find anything to prove if he was. His father, who had first taught Ethan’s sister, and then Ethan, to throw the hammer at the Nanaimo Track and Field Club, is named Bernie. That sounds pretty Jewish too! His mother – Coralee – not so much.

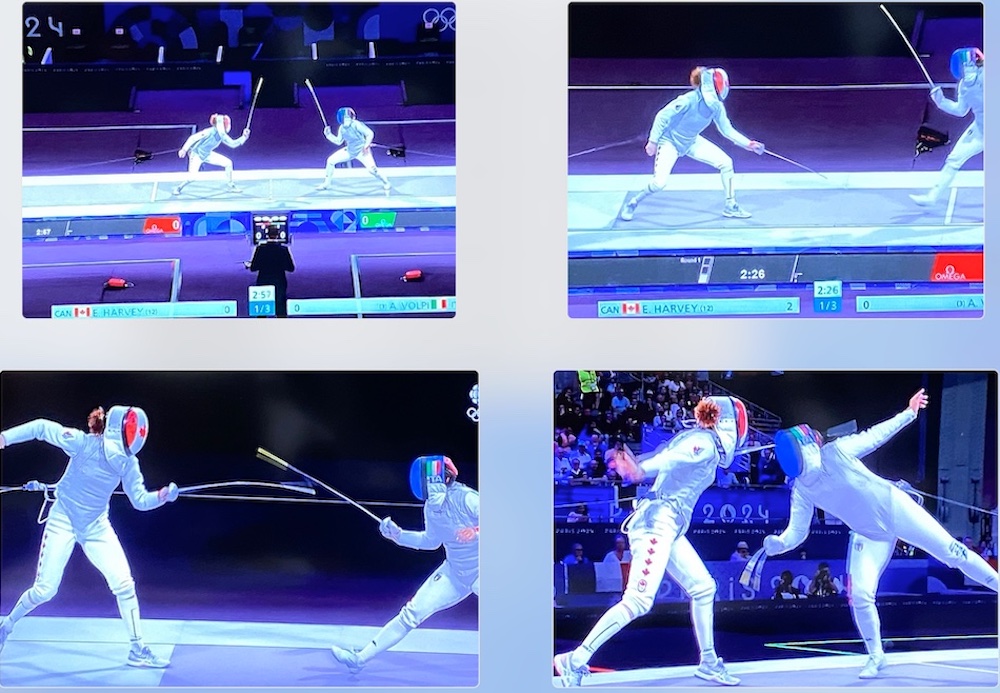

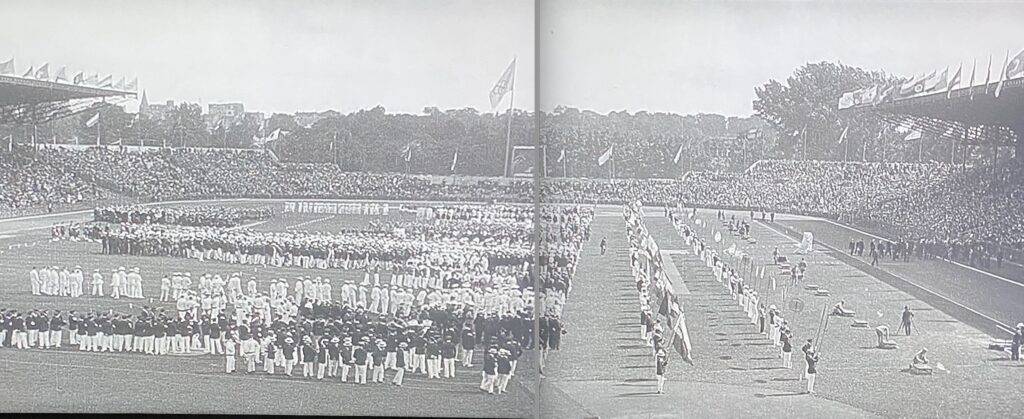

Canada’s flag bearers at the Closing Ceremonies.

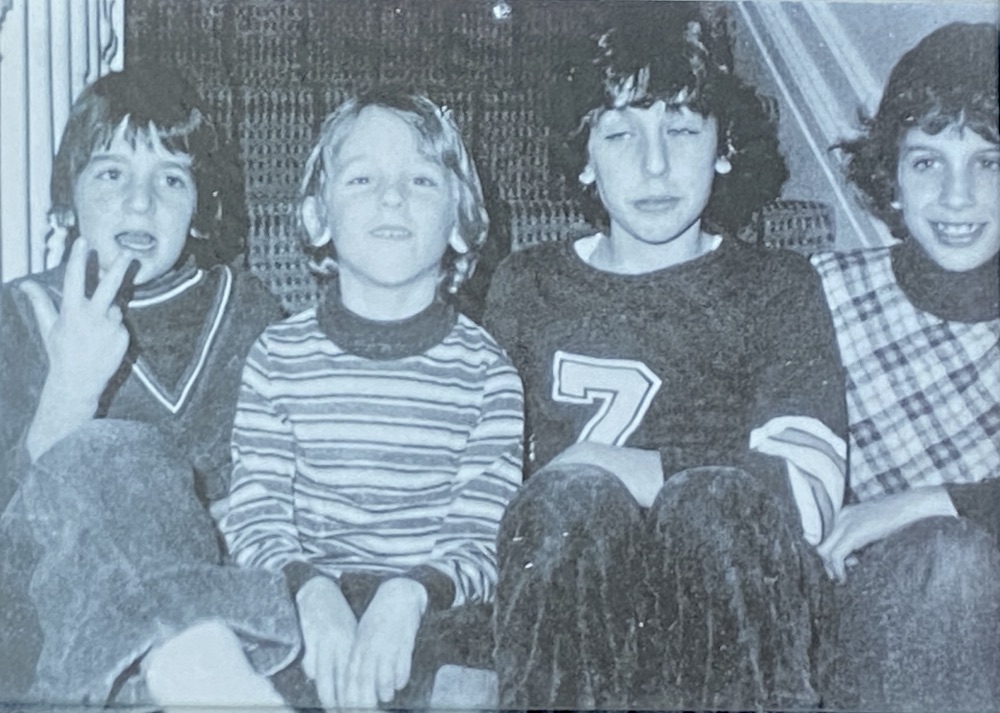

I soon came across a Nanaimo News Bulletin story from 2013 about Mike Gogo’s Christmas Tree farm, which had been in his family for 84 years. Included is a picture of the Katzberg family, who had just picked out their tree! It was, apparently, their first time tree hunting … in Nanaimo, at least.

“A light came down from the sky and illuminated it from above,” joked Bernie. “And the kids helped pick it out too,” Coralee added, also stating that the family loves authentic trees. “The real ones are better,” Coralee said. “They smell good.”

Plenty of mixed marriage Jewish families out there who celebrate Christmas and Hanukkah. Was this a case of that? “My guess,” I texted my brothers and nephew “is his Dad is Jewish and his Mom is not.”

Clearly, we weren’t the only people wondering, as other queries started showing up online. There was a particularly long thread on Reddit … which would seem to show that Katzberg is NOT Jewish. As one comment noted:

Ethan and I went to the same high school (years apart). I was so proud of him today! The Jewish community is pretty small in Nanaimo and I haven’t seen his name mentioned anywhere, so I don’t think he’s Jewish.

Still, maybe a Jewish father and a non-Jewish mother? Plenty of other commenters thought that was possibile … but it doesn’t appear so according to these two comments from somebody else:

No he is not Jewish. I went to school with his father at a German Baptist college in Alberta.

Bernie’s family (of origin) attended Baptist church, so not Jewish. His ethnicity is German and he speaks (some) German. I went to school with him during our late teens.

But fear not, Jewish sports fans, there’s plenty more Jewish sports content in the rest of what I’m going to write. Admittedly (though I’m not much of a basketball fan) I was intending to write this in celebration of Canada’s first basketball medal since 1936. That drought continues, but still…

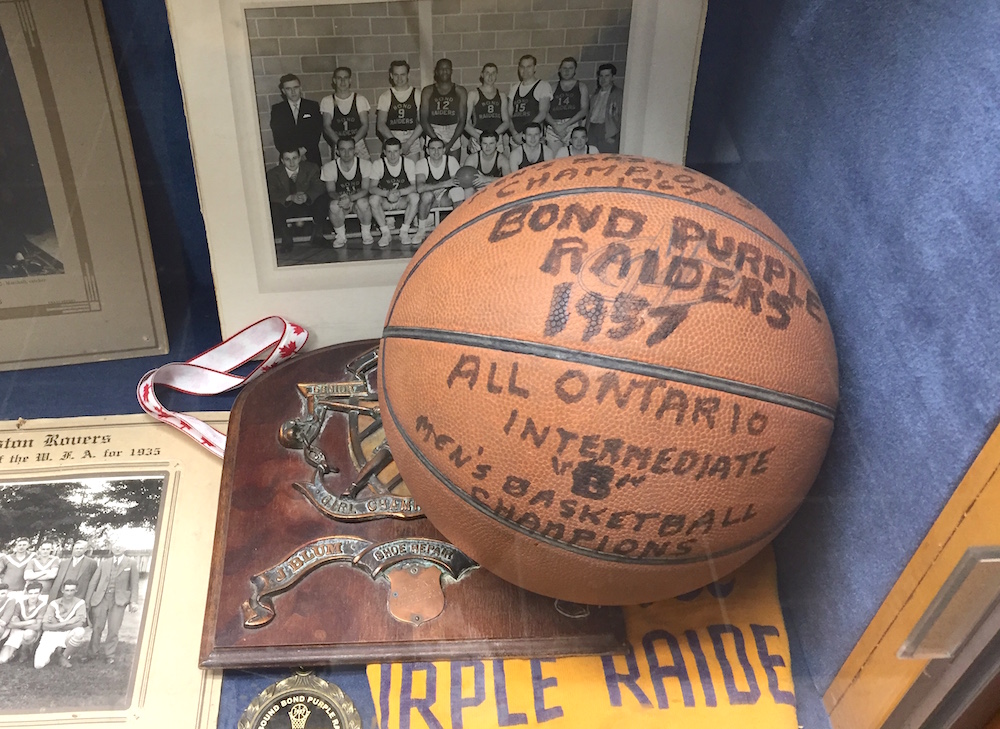

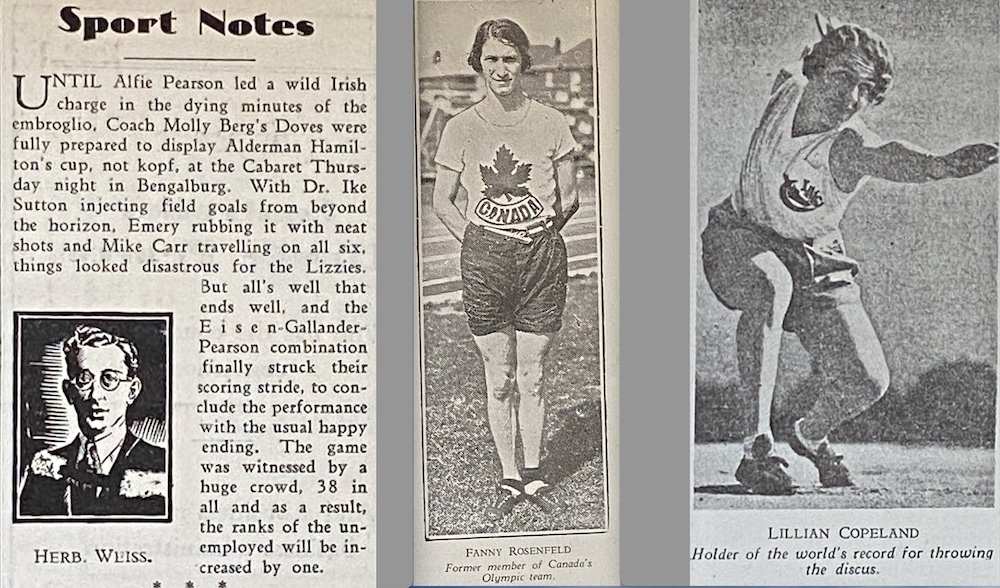

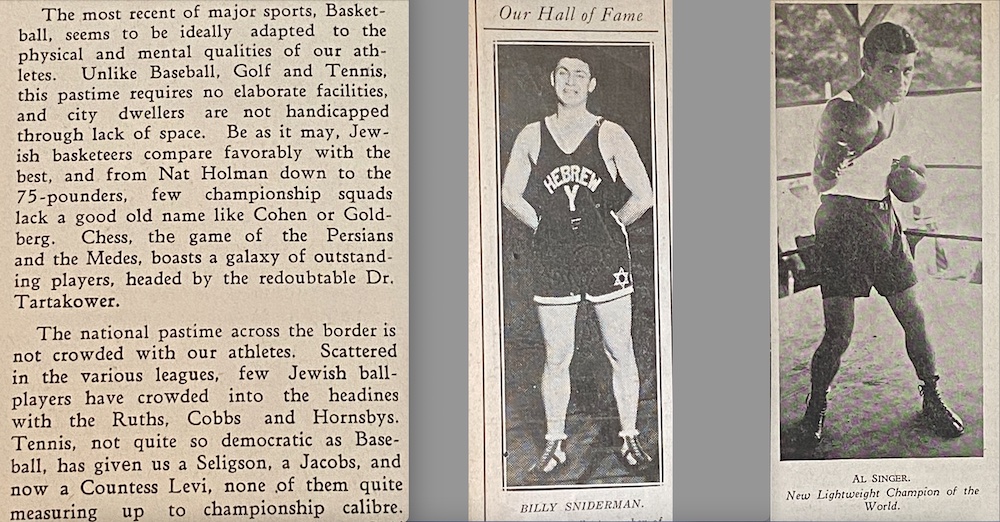

The common Jewish stereotype is that Jews are sports fans, but more likely to be team owners than athletes. But back in a time when Jews mostly lived in the inner city, sports were seen as a way to assimilate. Even a way to a better life. Back in the day, there were Jewish track stars, Jewish boxers, and Jewish basketball players too.

The 1936 Olympics had been awarded to Berlin in 1931, a few years before Adolph Hitler came to power. As the time drew closer, there were those who were pushing for the International Olympic Committee to move the Games somewhere else. Apparently, the most the IOC was willing to do was to push the Germans to include one token Jewish athlete on their Olympic team. Many Jewish athletes from around the world refused to go to Berlin and planned to attend The People’s Olympiad in Barcelona instead, but this leftist-inspired competition was called off shortly before it was to start due to the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War.

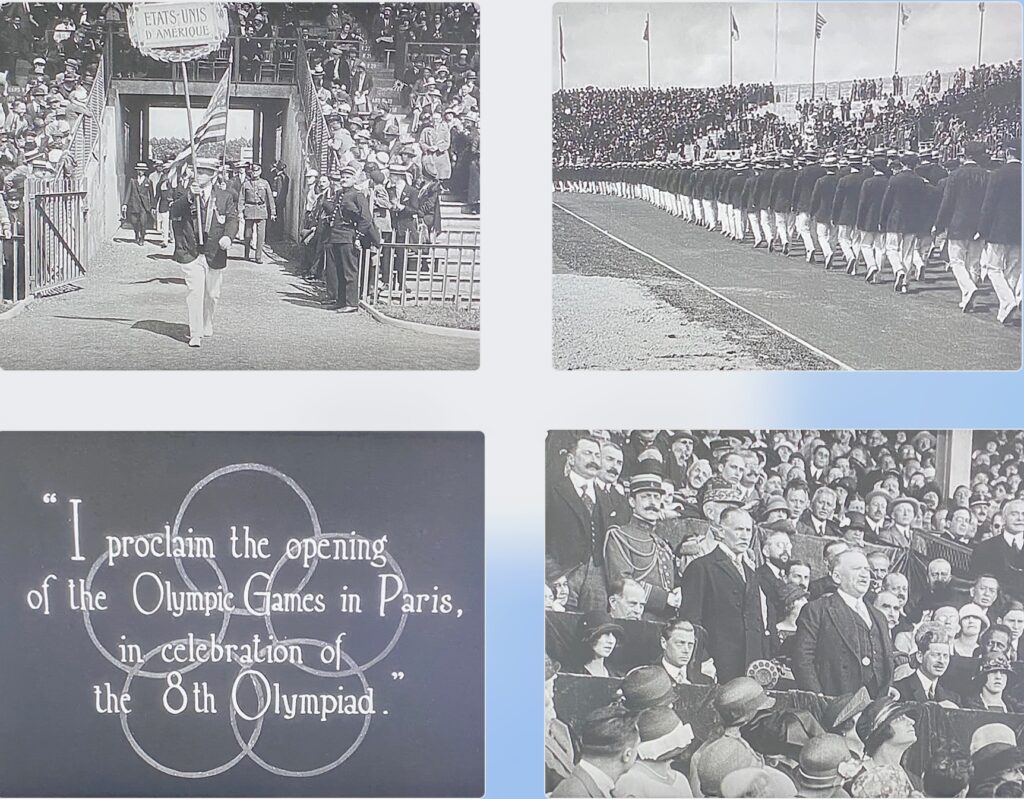

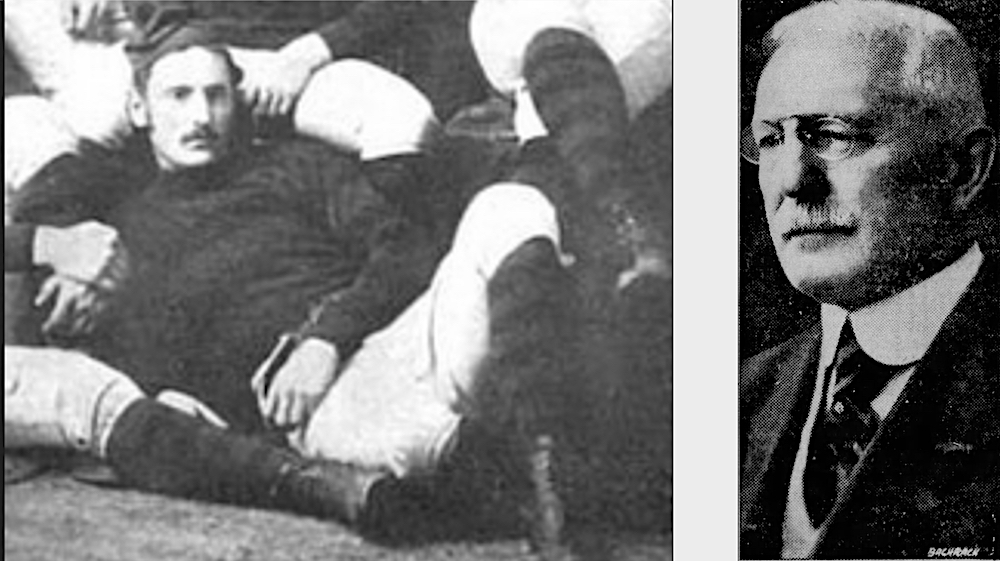

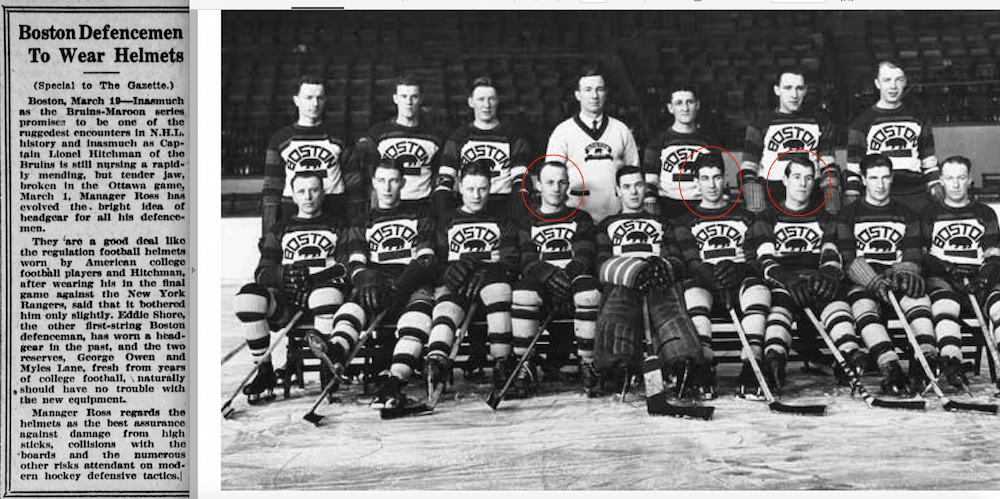

The Jewish Standard in 1931. (Courtesy Michael Hayman.)

Still, a handful of Jewish athletes did attend the Berlin Olympics … including two members of Canada’s basketball team which won a silver medal at the first Games where basketball was a full medal sport.

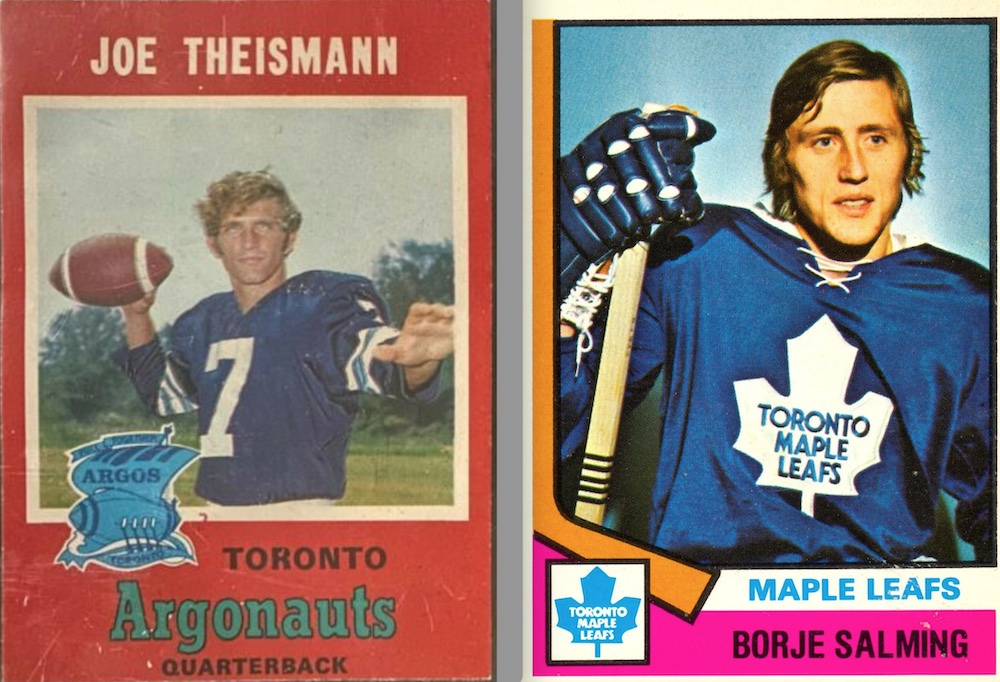

It’s often said that Canada was represented in basketball at the 1936 Berlin Olympics by the Windsor Ford V8 team. That’s only mostly true. The Ford V8s were the 1935-36 Canadian Senior Basketball Champions, but for the Olympics they picked up four members of the runner-up Victoria Blue Ribbons. (Windsor, Ontario – said to be because of its proximity to the United States – and Victoria, British Columbia, were the hotbeds of Canadian basketball at this time.) The Windsor team included two Jewish players: Irving “Toots” Meretsky and Julius “Goldie” Goldman.

Though he had moved to Canada when he was two years old, Goldman had been born in Mayesville, South Carolina, to Lithuanian immigrant parents. Being American-born, he wasn’t allowed to play for Canada, so instead served as an assistant coach and the team’s representative on the 1936 Olympic Basketball Rules Committee. It was in that capacity that Goldman would modernize the game by suggesting the jump ball to restart play after every basket be eliminated … although this rule change would not be implemented until after the Berlin Olympics.

Irving Meretsky was born in Windsor in 1912 and lived his whole life there. When he died in 2006 at the age of 94, he was the last surviving member of the 1936 Olympic basketball team. A 2015 story by Tony Atherton of Postmedia News on the web site of Canada Basketball tells an anecdote Meretsky must have told many times in his life about seeing Adolph Hitler at the Opening Ceremonies:

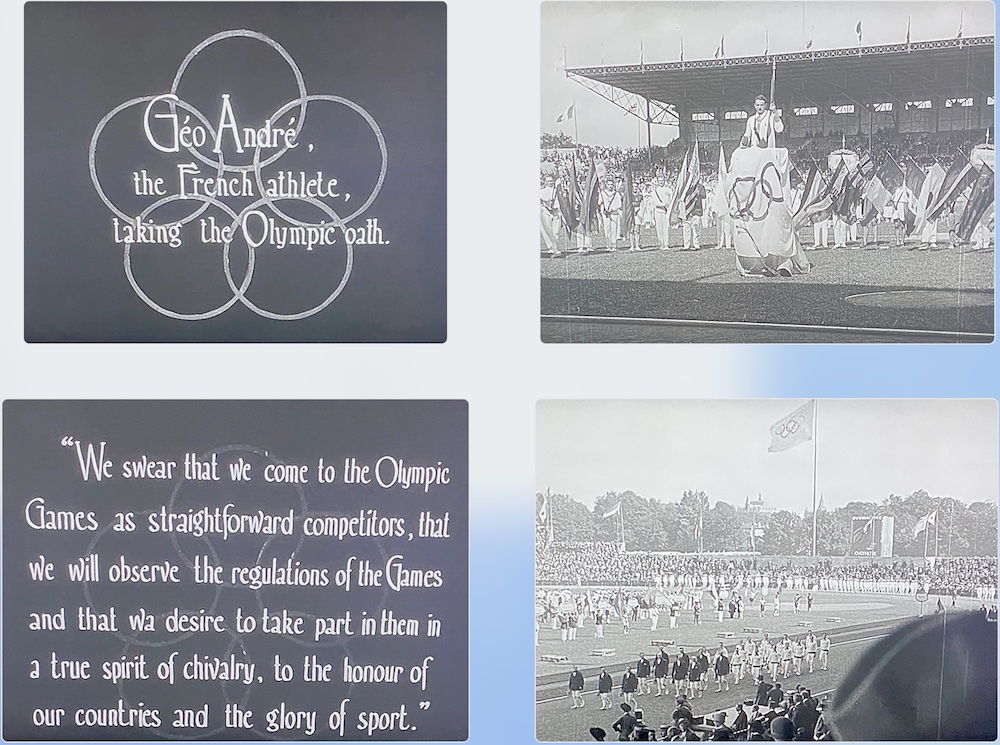

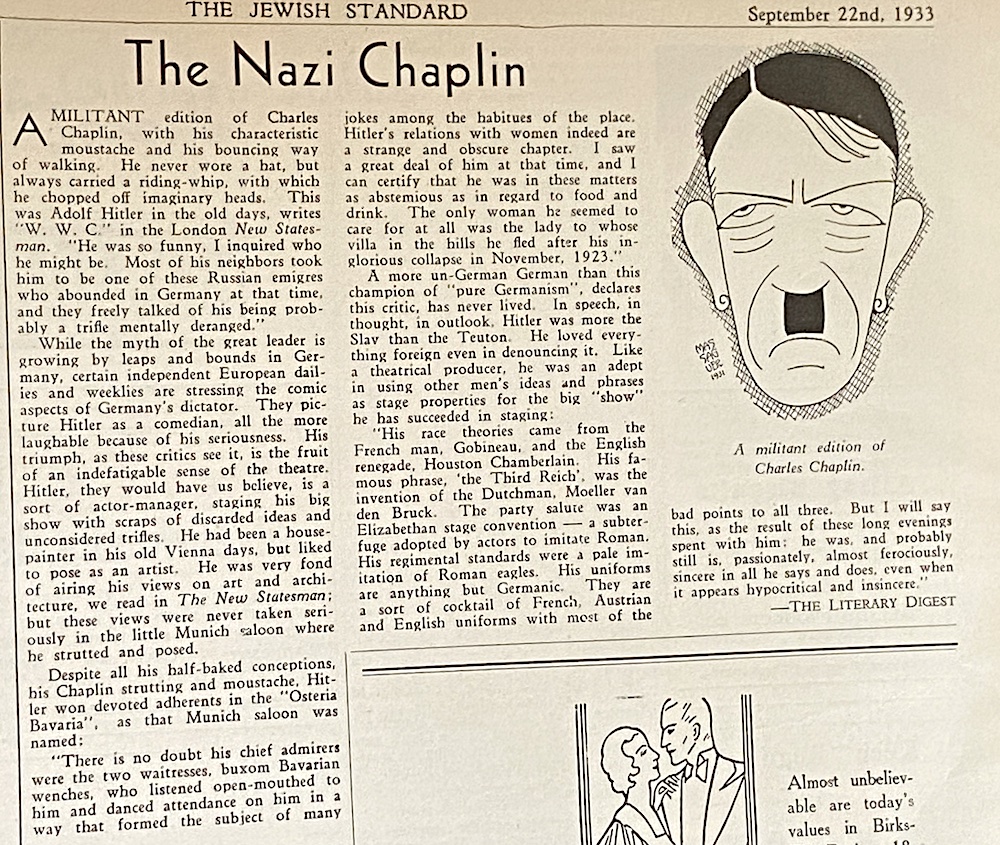

Down on the field, among the ranks of athletes from 52 nations, a skinny 24-year-old in a red blazer and white ducks, a Maple Leaf upon his breast, couldn’t keep an impish smile from spreading across his face. “He looks like Charlie Chaplin!” Toots Meretsky told himself. And no doubt felt better for it.

Toots was a Jewish kid from Windsor, Ont., standing in the heart of Nazi Germany, staring up at Hitler – on Shabbat, no less. He had passed ranks of crimson, swastika-emblazoned banners on his way into the arena. Now, he was hemmed in by an honour battalion of the German army. Everywhere he looked there were brownshirts, blackshirts, and blond, ecstatic Hitler Youth. He knew of the systematic oppression of German Jews since the Nazis had come to power three years before. He knew about the boycotting of Jewish businesses, the revocation of citizenship, the edicts against intermarriage, not to mention the random vandalism, beatings, and intimidation.

But Adolf Hitler looked like Charlie Chaplin. So Toots had to smile.

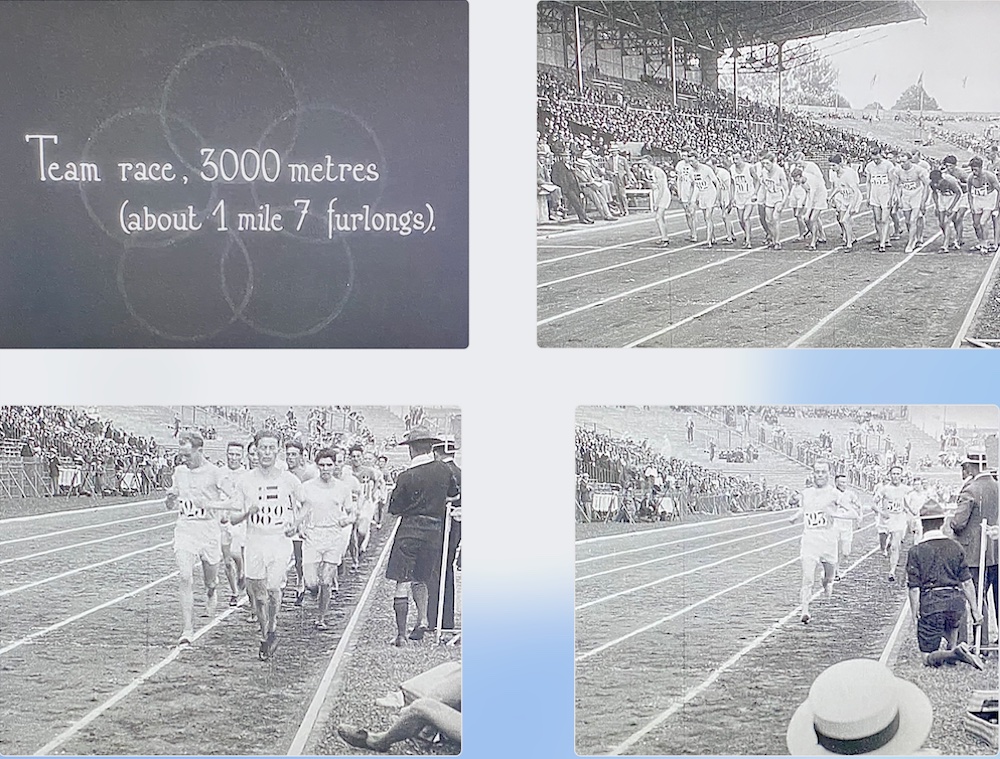

Basketball was almost an afterthought at the Berlin Olympics. The Germans didn’t think fans would care to watch, so the games were played on a modified outdoor clay tennis court. Mainly because of the jump ball rule, the lack of a 24-second clock (which wouldn’t come to be until the 1950s) and the fact that goaltending wasn’t against the rules, basketball was much more lowing scoring in this era. En route to the gold medal game against the United States, Canada posted the following victories:

24–17 over Brazil

34–23 over Latvia

27–9 over Switzerland

41–21 over Uruguay

42–15 over Poland

in 1936, but was happy to pose with the team from his home and native land.

The U.S. got a bye in the first round when Spain withdrew, and then won:

52–28 over Estonia

(Bye through the third round)

56–23 over Philippines

25–10 over Mexico

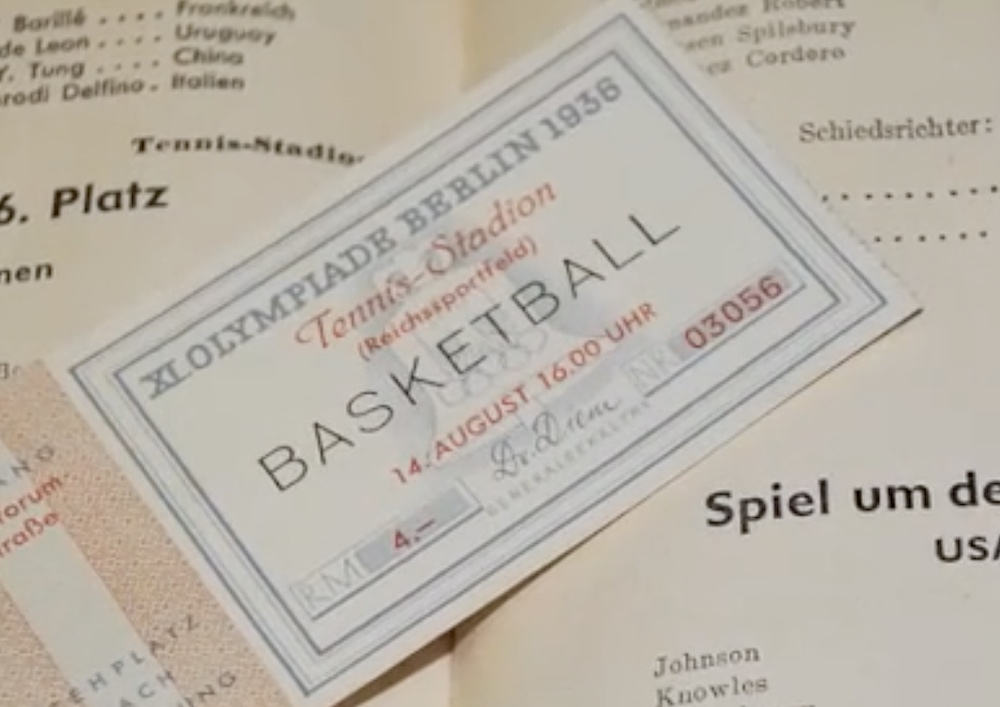

Rain would mar the championship game on August 14, 1936.

Years later, [Canadian] team member Gord Aitchison would describe the scene to the Windsor Star. “On the opening play, an American player raced down the court, caught a pass as his feet went from under him and completed the last 15 or 20 feet to the basket sliding on the seat of his shorts, water spraying out from both sides.” The rest of the game followed suit.

Sam Balter, a U.S. point guard (and the only Jewish-American medal winner in 1936) regretted the circumstances of that game for the rest of his life, he told Sports Illustrated. “A comedy of errors and unfortunate circumstances had combined to make a sandlot affair of what should have been the greatest basketball tournament ever,” he said.

The jump ball rule meant the height advantage of the American team would have been big at any rate, but on a soggy court where dribbling was impossible and even passing the ball was difficult, it proved a huge advantage. The U.S. led 15–4 at halftime, and while the Canadians played them even in the second half the final score was 19–8.

Unfortunately, the Olympic Committee had only minted seven medals of each color for the basketball competition. The Canadians drew lots to determine which of their players would receive a silver medal. Toots Meretsky didn’t win … however, after a media stir about the oversight, the IOC minted a new silver medal for Toots in 1999 from the original mold.

“Our group of guys were the greatest in the world,” Toots told a sports website sometime before his death in 2006 broke the last direct link with Canada’s only Olympic medal winning basketball team. “We all helped one another, we worked together, we played together.”