Over a three-month period 90 years ago, during the fall of 1926, three of the greatest sports stars of the Roaring Twenties made appearances in Toronto. A time-machine type of moment for someone like me, and yet – given the historical significance of these performers – they don’t appear to have attracted the size of crowds they should have.

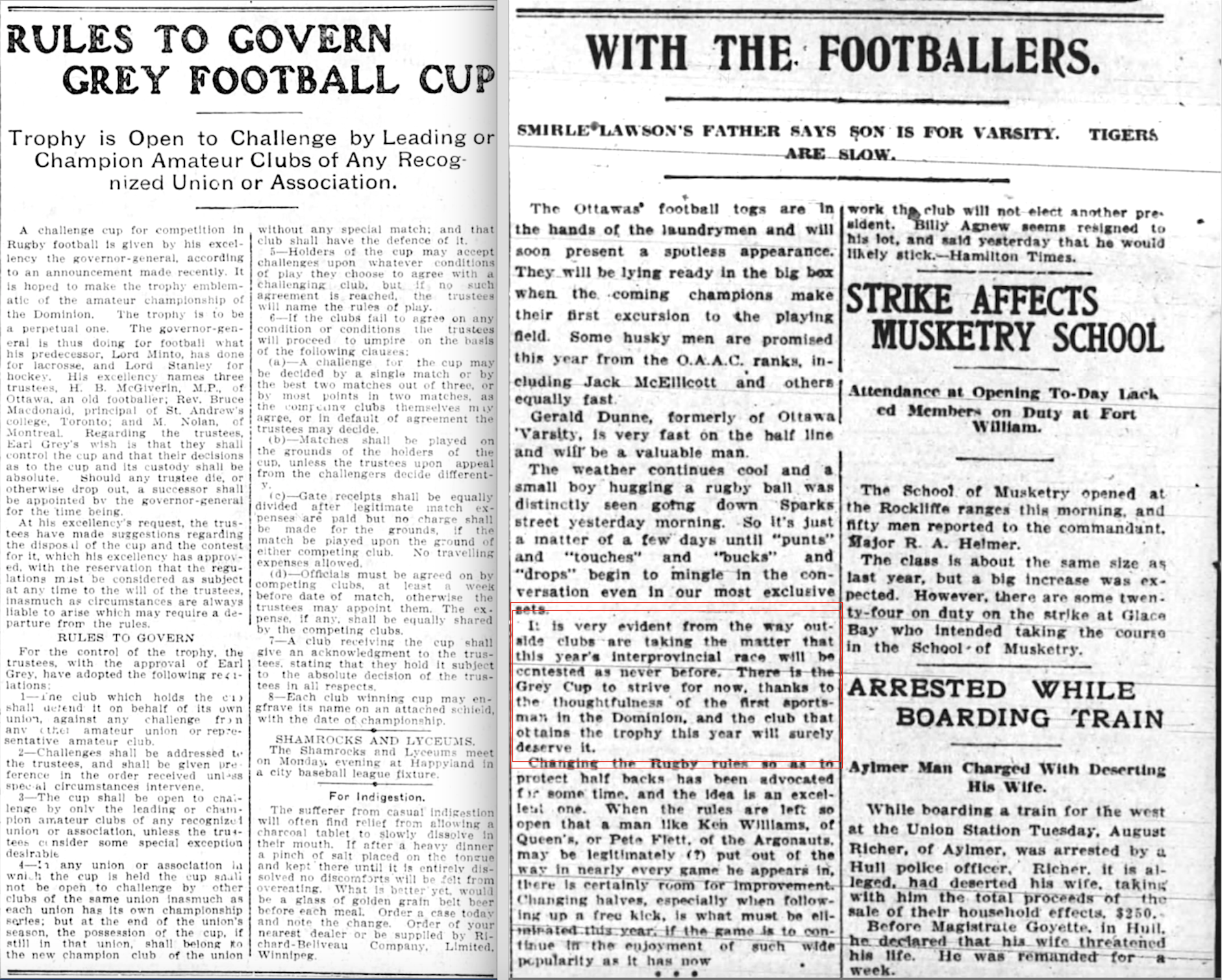

First up was Babe Ruth, who appeared on a Friday afternoon, September 10, 1926, for an exhibition game between the New York Yankees and the Toronto Maple Leafs baseball team. The Yankees featured most of their star players, including Tony Lazzeri, Mark Koening and Bob Meusel, although Ruth played first base in this game and when Lou Gehrig came in late it was as the right fielder.

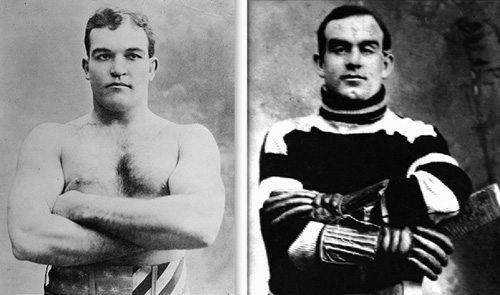

Photograph from the Toronto Star, box score from the Globe, September 11, 1926.

The Leafs, behind soon-to-be New York Giants star Carl Hubbell, led 2-1 for most of the game before the Yankees scored four in the eighth and three in the ninth for an 8-2 victory. The whole game was played in just an hour-and-a-half! Only about 6,000 fans showed up at Maple Leaf Stadium, and by most accounts, it wasn’t much of a game. The crowd had come to see Ruth hit home runs, but he managed only two singles. Still, he was swarmed on the field by about 100 young boys the moment the game ended.

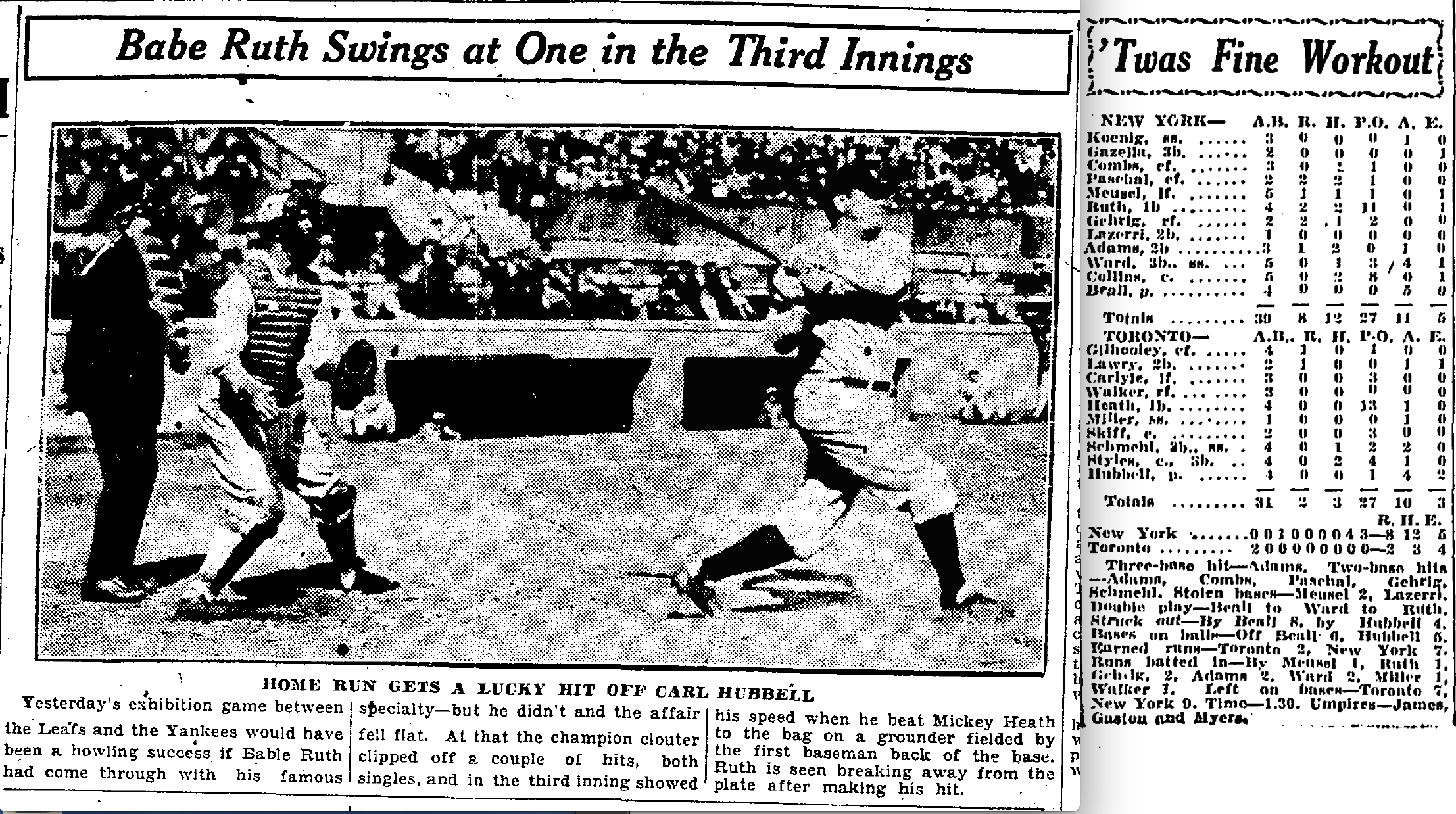

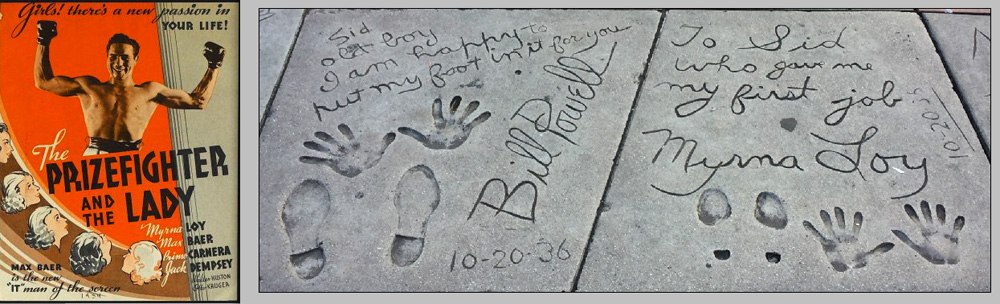

A month later, on October 12, 1926, tennis star Suzanne Lenglen of France was in Toronto. Lenglen was the Serena Williams of her day. Not only was she the world’s most dominant female tennis player, she helped to change tennis fashions and was a hard-nosed businesswoman. In an era when tennis was strictly amateur, she was the first to become a professional. In fact, that’s what brought her to Toronto. It was her second stop on a pro exhibition tour across North America that had begun at Madison Square Garden in New York two nights before.

Lenglen’s star power had made tennis a popular spectator sport, and while I couldn’t find a specific attendance figure for her exhibition at Toronto’s Arena Gardens, stories note it was a large and particularly well-dressed crowd. Lenglen defeated American Mary Browne 6-0, 6-2 in a singles match, but she and her French partner Paul Feret were defeated by Browne and fellow Californian Harvey Snodgrass in mixed doubles.

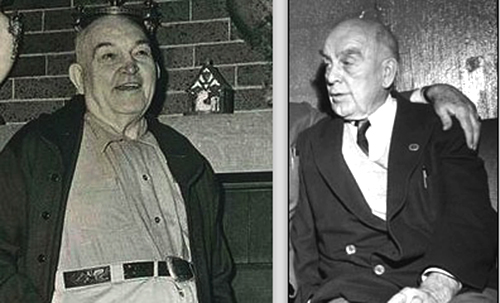

Photo from the Toronto Star, October 13, 1926. Lenglen is wearing the head scarf.

Of particular note throughout her tour was the question of why Lenglen had turned pro – a widely criticized decision that saw the All-England Club at Wimbeldon (where she had won six championships in a seven-year span) revoke her honorary membership. Lenglen was up front about it, saying she did it for the money. She estimated that she’d made millions of francs for others while spending thousands of her own on entrance fees.

“I have worked as hard at my career as any man or woman has worked at any career. And in my whole lifetime I have not earned $5,000 – not one cent of that by my specialty, my life study – tennis…. I am twenty-seven and not wealthy – should I embark on any other career and leave the one for which I have what people call genius? Or should I smile at the prospect of actual poverty and continue to earn a fortune – for whom?

“Under these absurd and antiquated amateur rulings, only a wealthy person can compete, and the fact of the matter is that only wealthy people do compete. Is that fair? Does it advance the sport? Does it make tennis more popular – or does it tend to suppress and hinder an enormous amount of tennis talent lying dormant in the bodies of young men and women whose names are not in the social register?”

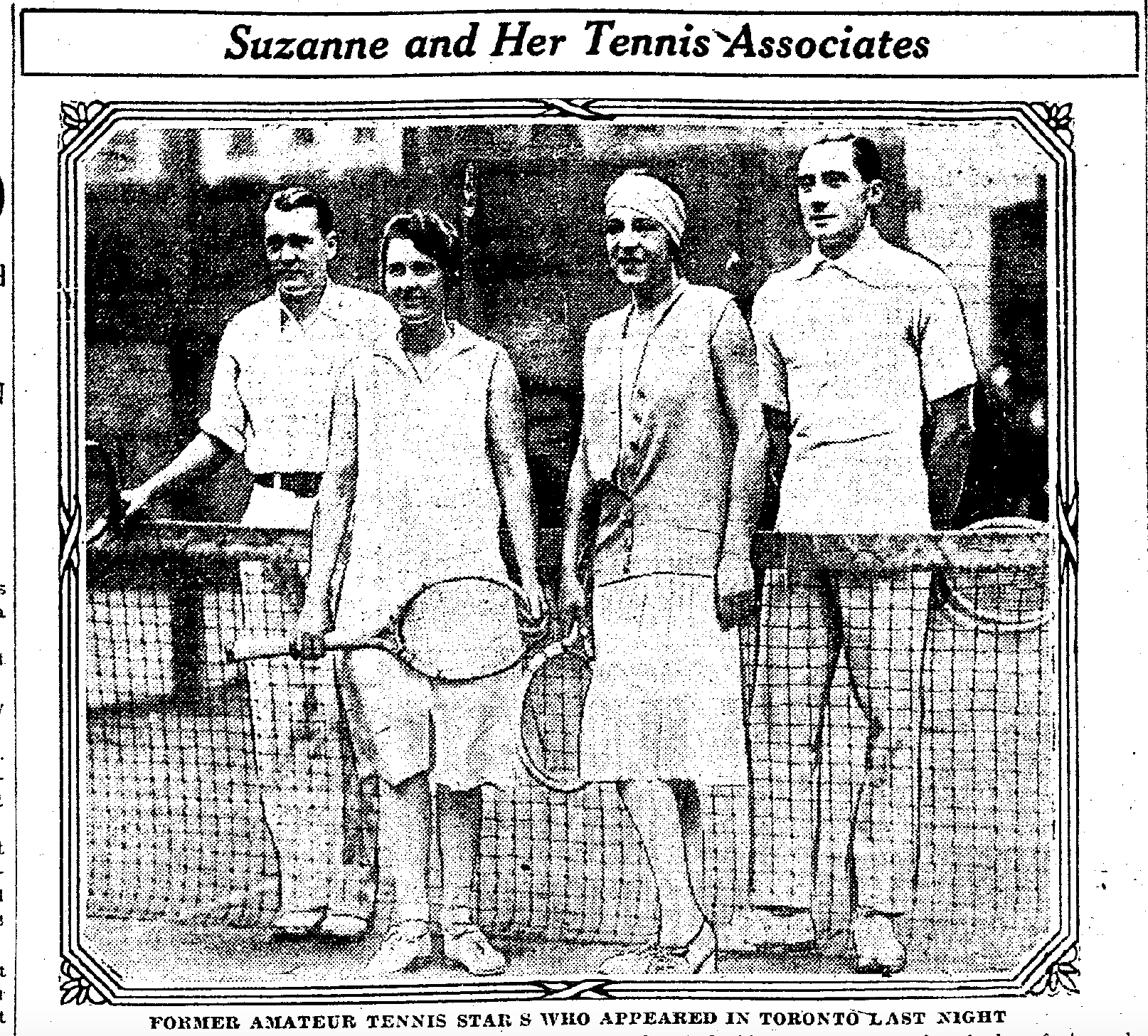

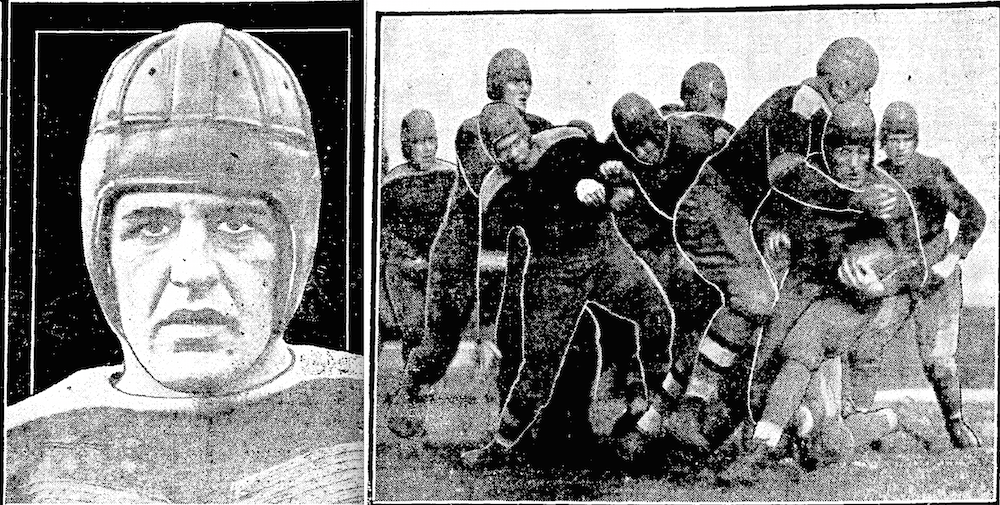

Another professional pioneer was in Toronto the next month, on November 8, 1926, when Red Grange was in town to play football. Grange had been a star at the University of Illinois at a time when college football ruled the sport and the fledgling National Football League was barely an afterthought. Grange – known as “The Galloping Ghost” – changed all that with his decision to sign with the Chicago Bears in 1925. He drew huge crowds to NFL games that season, and as a barnstormer afterward, but when he got into a dispute with Bears owner George Halas, Grange and his agent C.C. Pyle (who also represented Suzanne Lenglen!) formed their own team and their own league the following year.

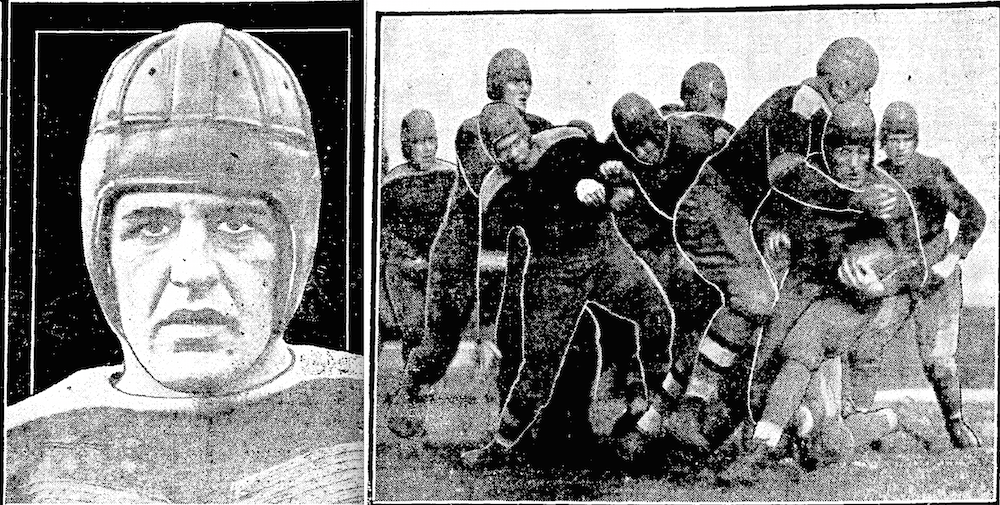

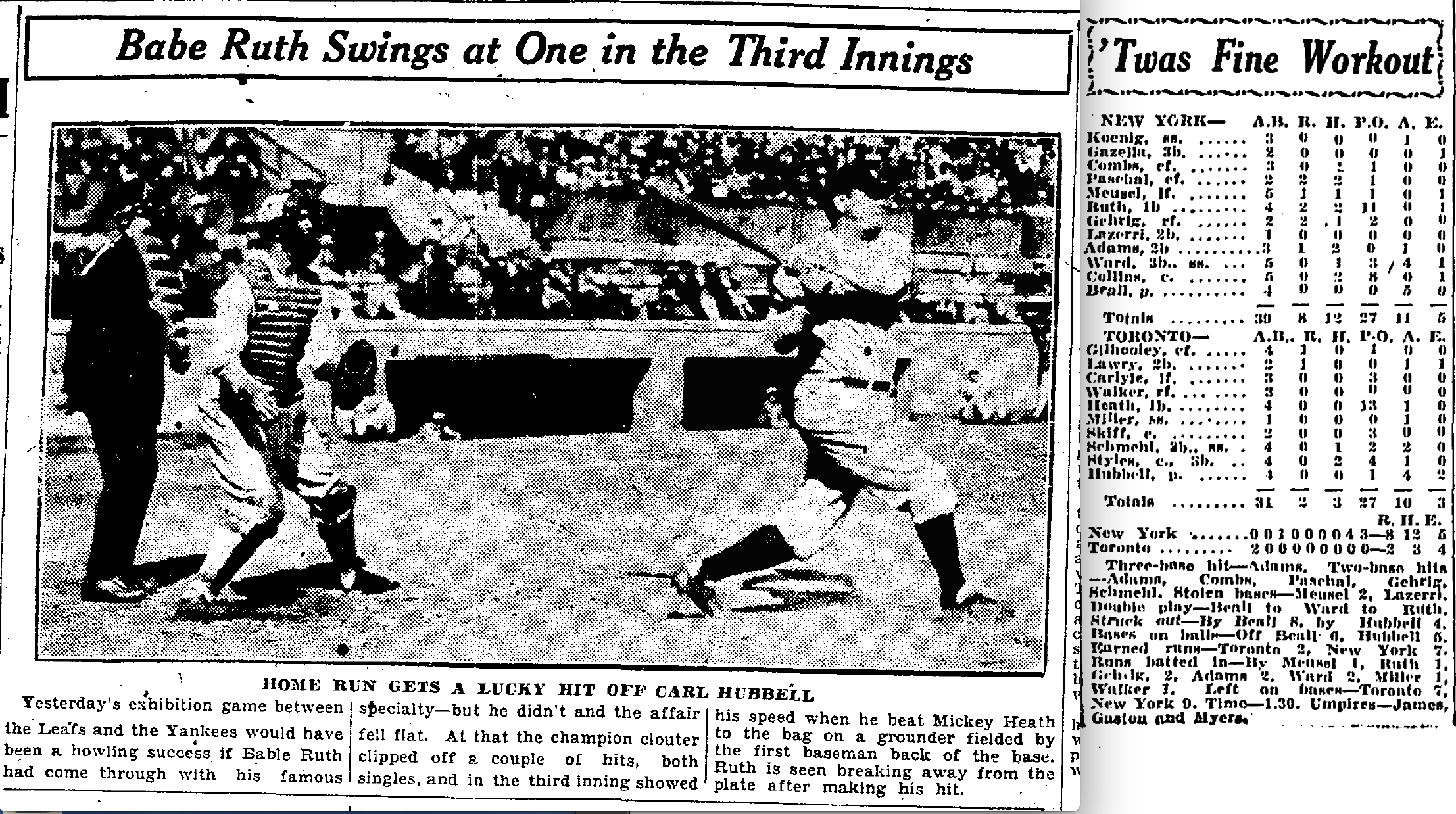

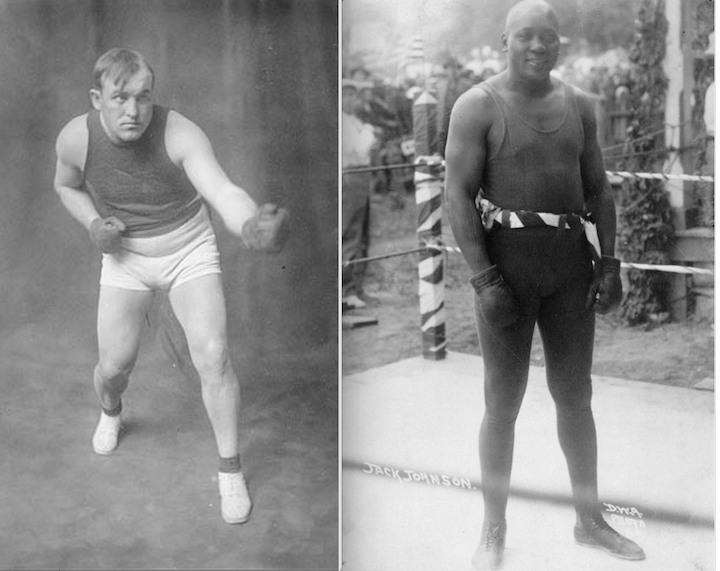

Red Grange on the left, an action shot of the game on the right.

From the Toronto Star, November 9, 1926.

Grange was playing with the New York Yankees of the American Football League when he came to Toronto for a league game against the Los Angeles Wildcats at Maple Leaf Stadium. Unlike the huge crowds he attracted in the United States, there were only about 10,000 to 12,000 fans at this game. After a scoreless first half, Grange scored on a 70-yard touchdown run and the Yankees went on to a 28-0 victory.

Legendary Toronto sportswriters W.A. Hewitt (father of Foster), Lou Marsh and Mike Rodden all covered the game. Given today’s NFL-envy among so many Toronto football fans, it’s interesting to note that these writers believed the Toronto crowd was unimpressed with the American rules. Too much passing; not enough running; and not enough kicking. (The game was called football, after all!) And where were the single points? Why didn’t the American players have to run back punts? Why wasn’t the ball turned over when the punting team downed it? Forward passing was not yet allowed in Canadian football, and the fans also wondered why it wasn’t a fumble when an incomplete pass hit the ground.

All in all, the Canadian fans (or, at least, the sportswriters) felt there were just too many rules in American football. And for his part, Grange – who attended a game between Balmy Beach and the Hamilton Tigers at Varsity Stadium earlier in the day – liked all the punting and the running … but he thought the Canadian game was too rough!

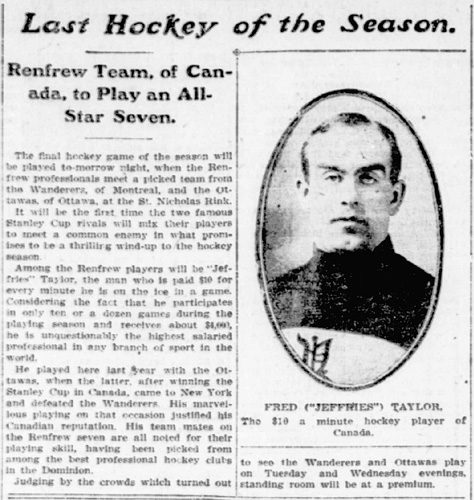

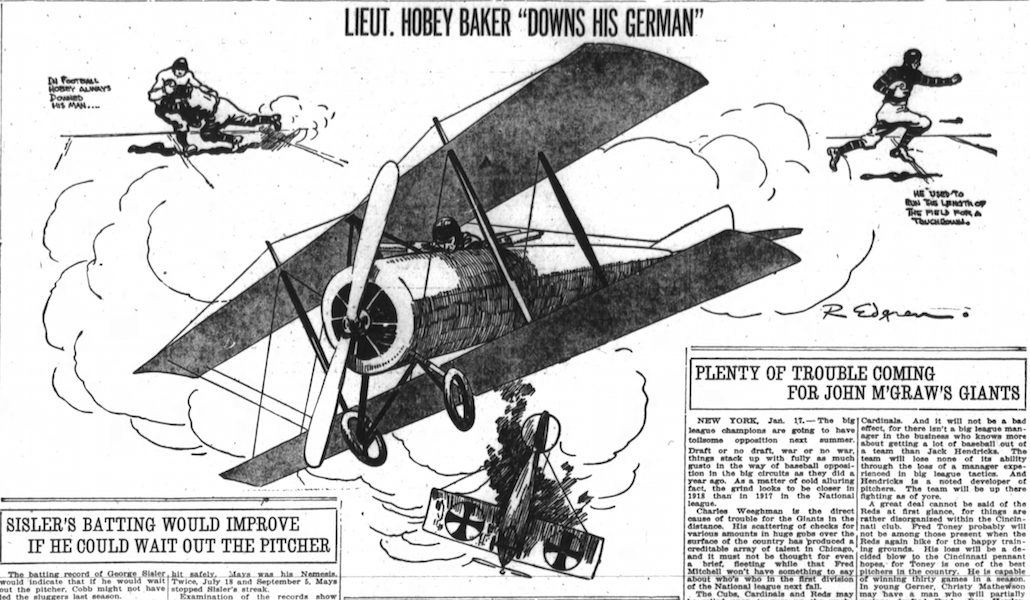

Article in The New York Daily Tribune on March 18, 1910, when Taylor

Article in The New York Daily Tribune on March 18, 1910, when Taylor

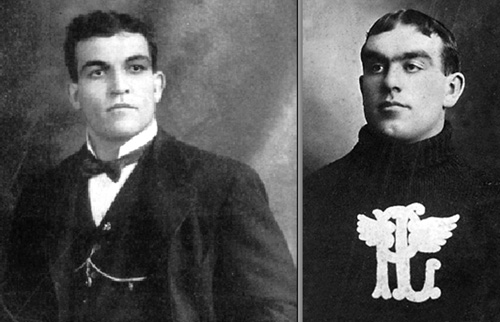

My first football team. I’m in the top row, next to our enormous coach.

My first football team. I’m in the top row, next to our enormous coach.

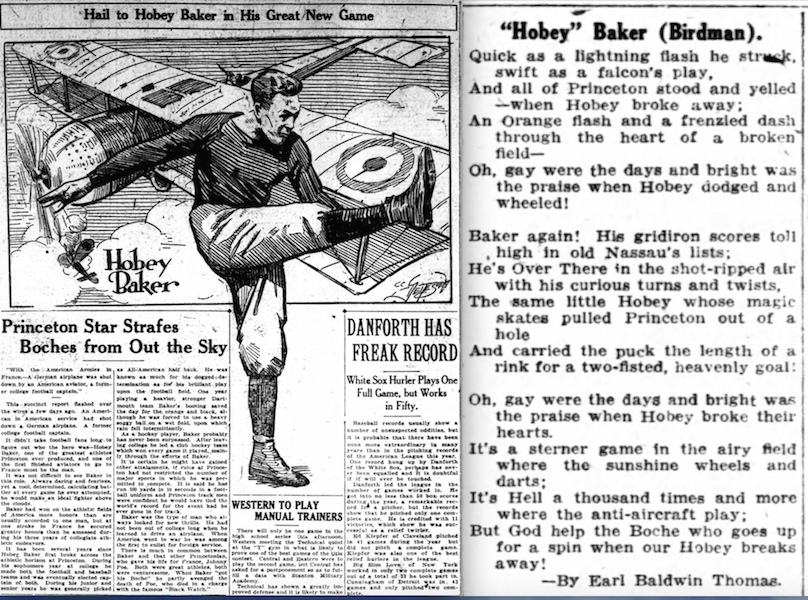

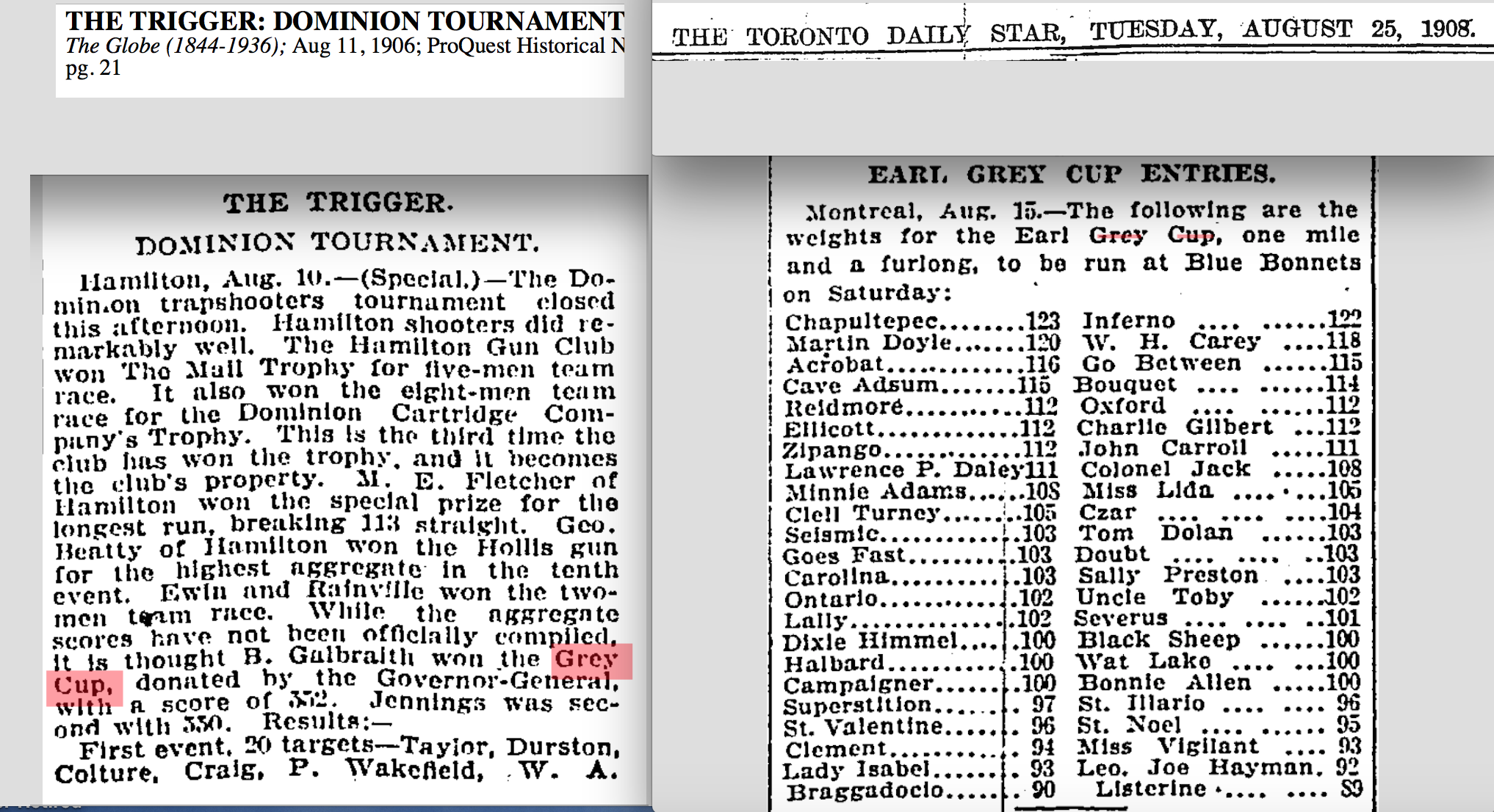

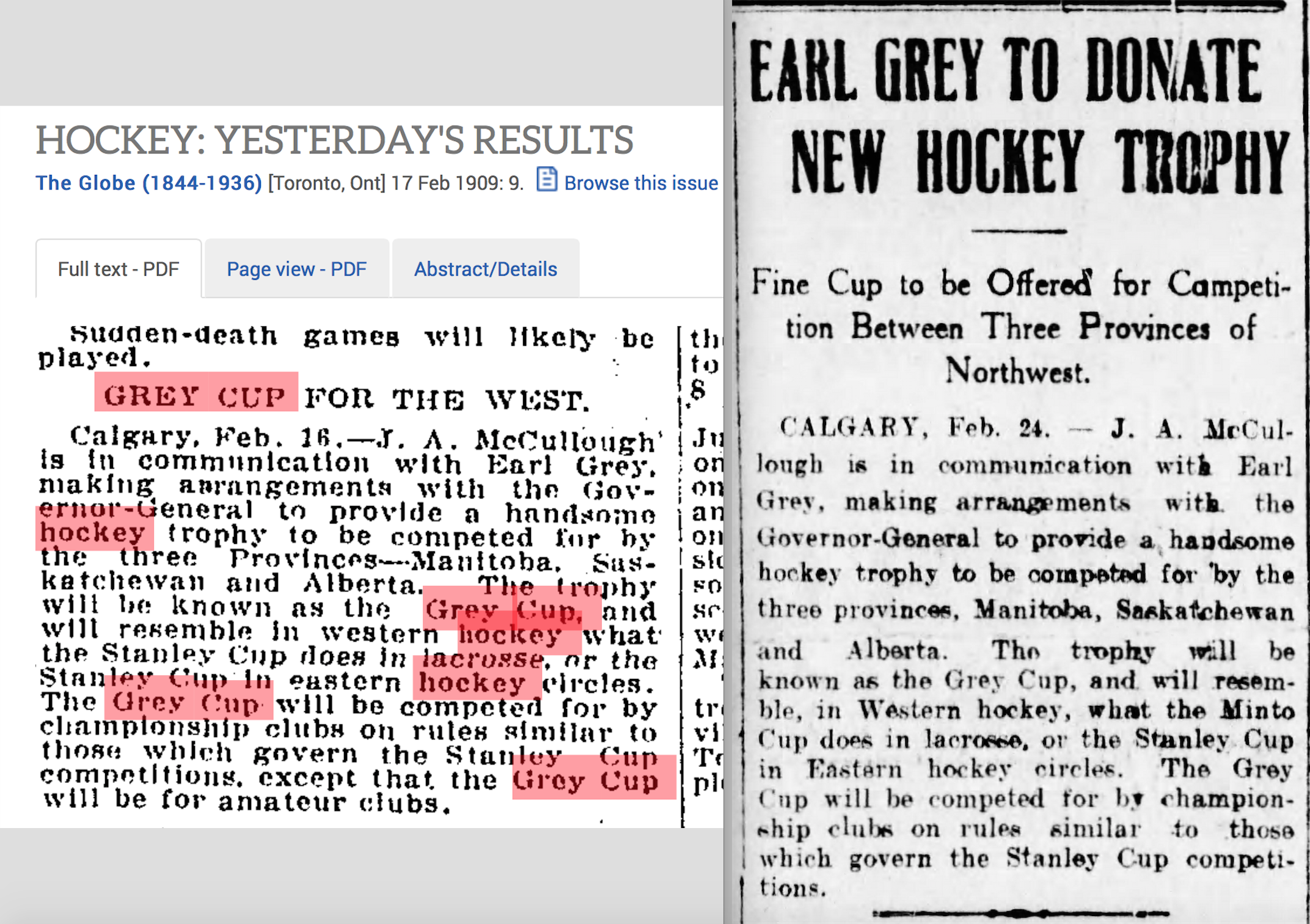

The article on the right is from Vancouver Daily World on February 24, 1909.

The article on the right is from Vancouver Daily World on February 24, 1909. From the Toronto Daily Star, June 1, 1909 and the Brandon Weekly Sun, June 3, 1909.

From the Toronto Daily Star, June 1, 1909 and the Brandon Weekly Sun, June 3, 1909.