This Saturday, the Maple Leafs will be wearing Toronto St. Pats uniforms for their home game against Chicago. It’s a nod to the team’s heritage during its 100th season and, of course, to the fact that Friday will be St. Patrick’s Day.

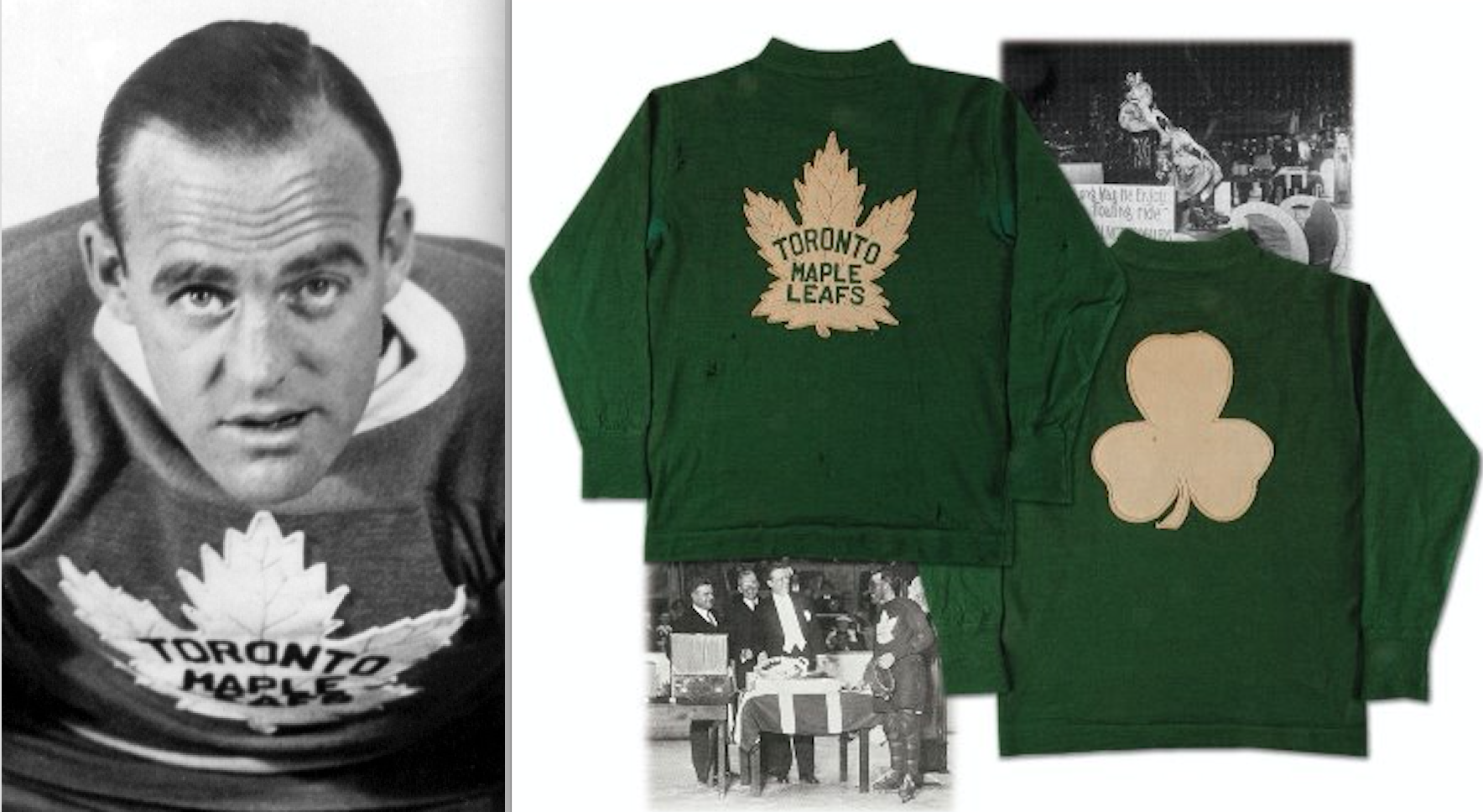

Way back on March 17, 1934, the Maple Leafs celebrated St. Patrick’s Day by declaring it “Clancy Night” in honour of King Clancy, their own Irish leprechaun whom Conn Smythe had acquired as the key piece he felt he needed to build the team into the powerhouse he envisioned. (Clancy did exactly what Smythe hoped he would and, basically – except for few years – remained with the Maple Leafs for the rest of his life.)

King Clancy wore this green shirt – sold a few years ago by Classic Auctions –

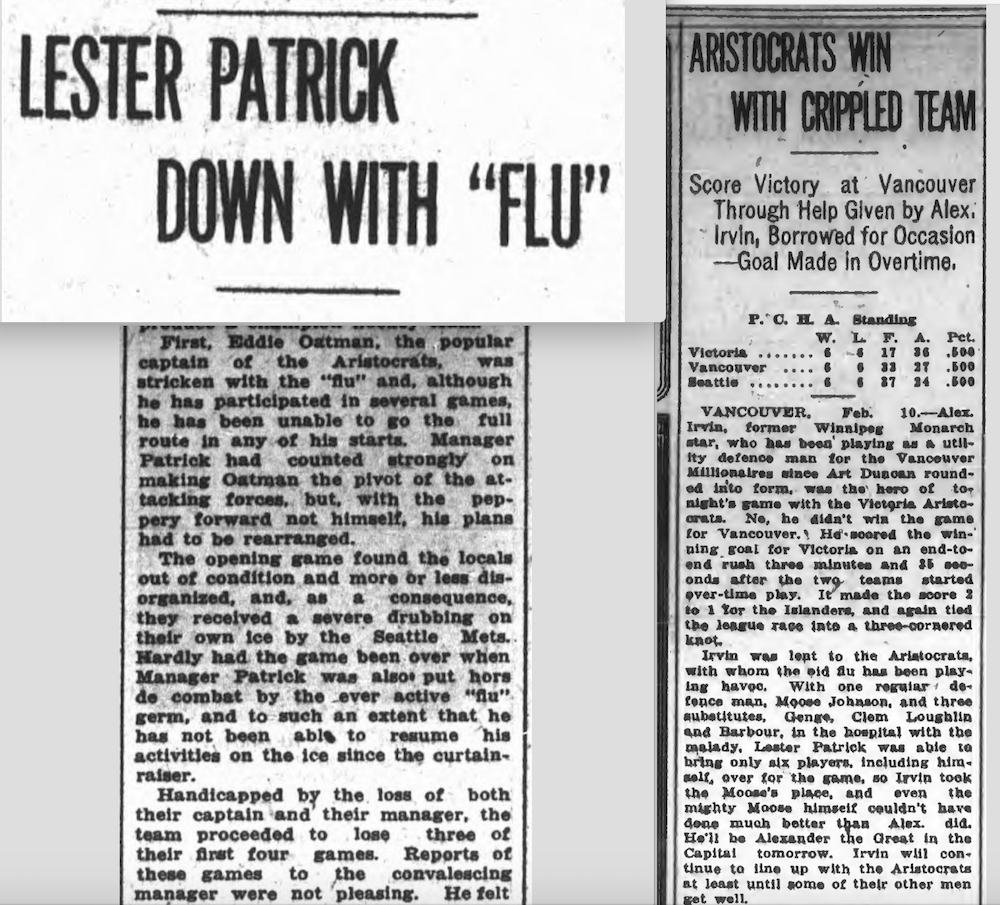

on Clancy Night in 1934 … until Lester Patrick of the New York Rangers

demanded he put on his regular Leafs uniform.

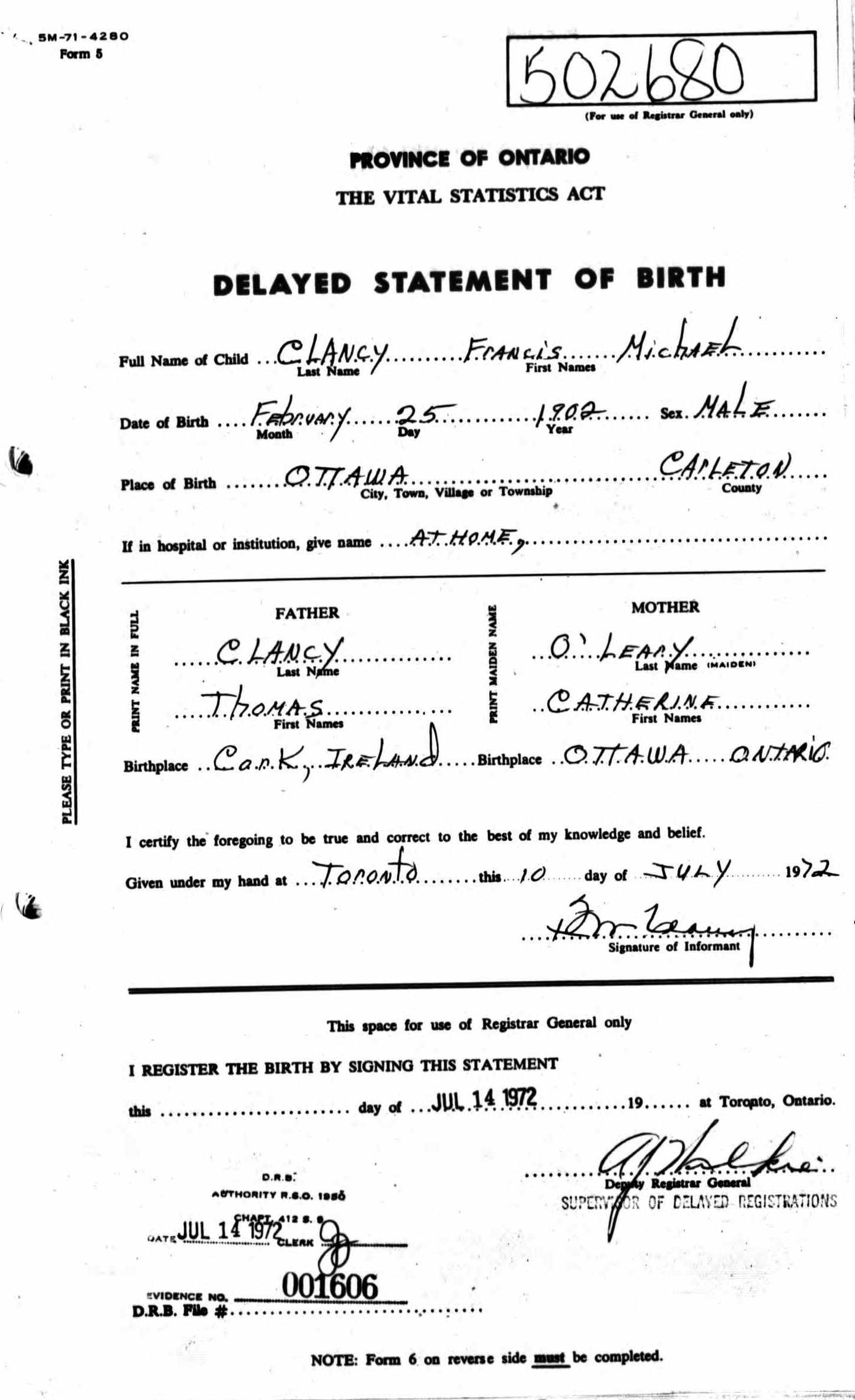

Over the past few years, a man I have never met named Daniel Doyon has been emailing me notes about the books I write and corrections to errors he’s come across in the NHL Official Guide & Record Book. (And, honestly, he’s never sent me anything where it hasn’t turned out that he was right!) A few weeks ago, on February 25, he sent me a note saying that it was King Clancy’s birthday and did our records show he was turning 114 or 115, because although hockey sources have long listed 1903 as Clancy’s birth year, he’d come across a document indicating it really should be 1902.

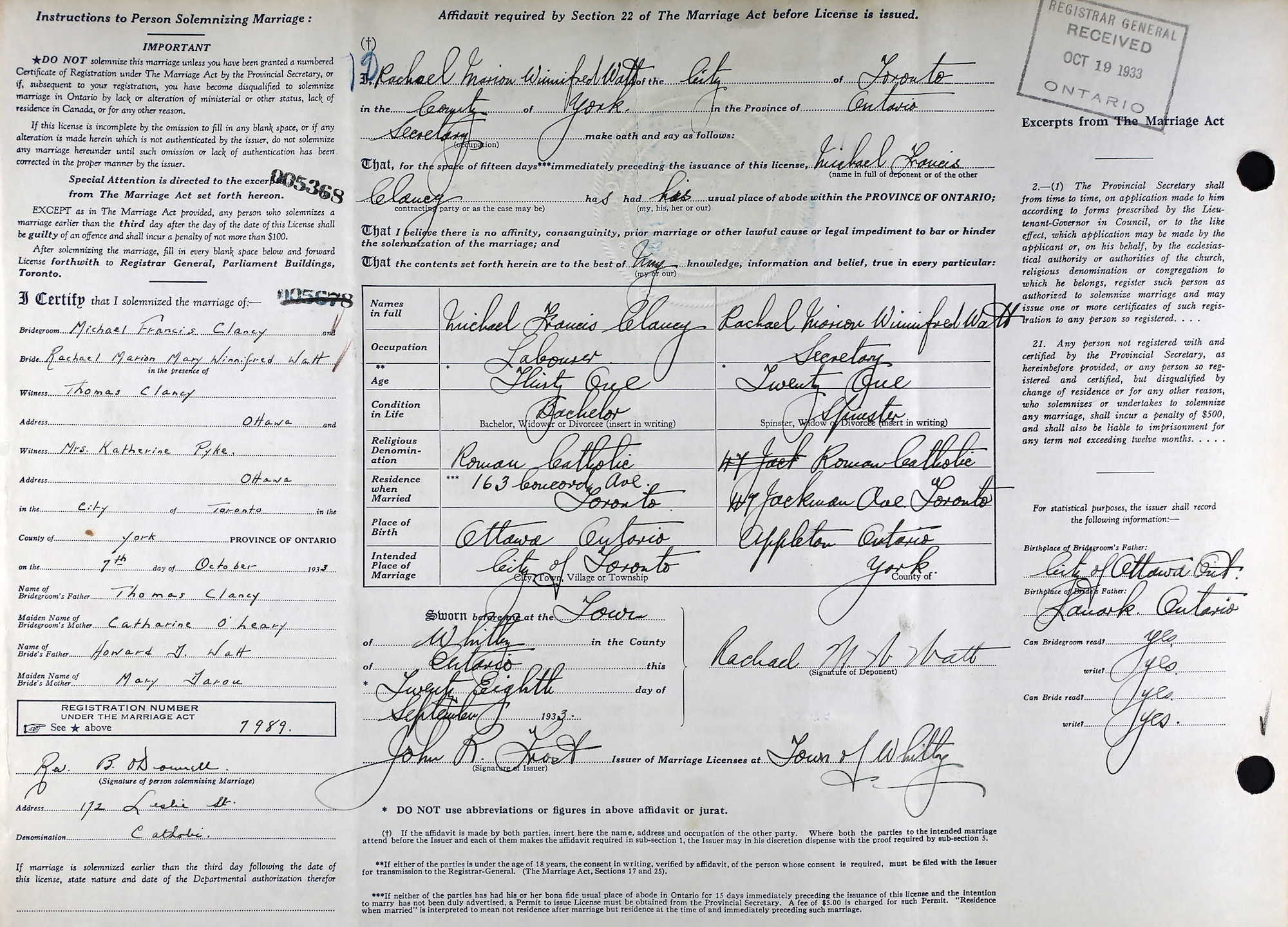

Even with web sites such as Ancestry.com and others like it, this type of research is far from perfect. Despite the fact that King Clancy himself signed this document stating that “I certify the foregoing to be true and correct to the best of my knowledge and belief,” it was still 70 years after the fact. He could have been wrong.

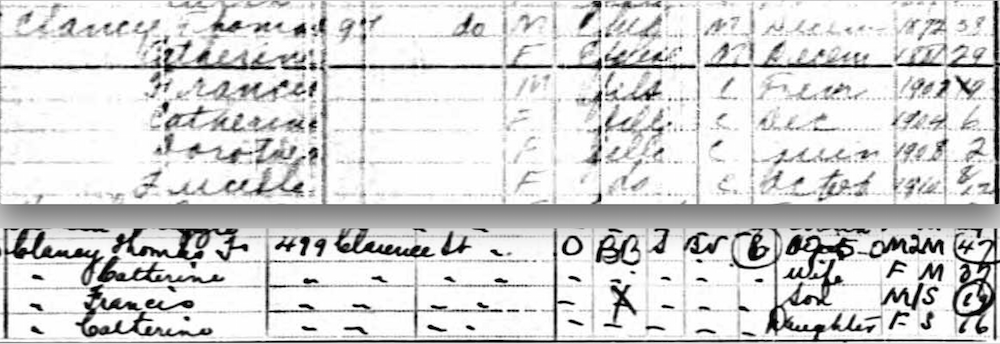

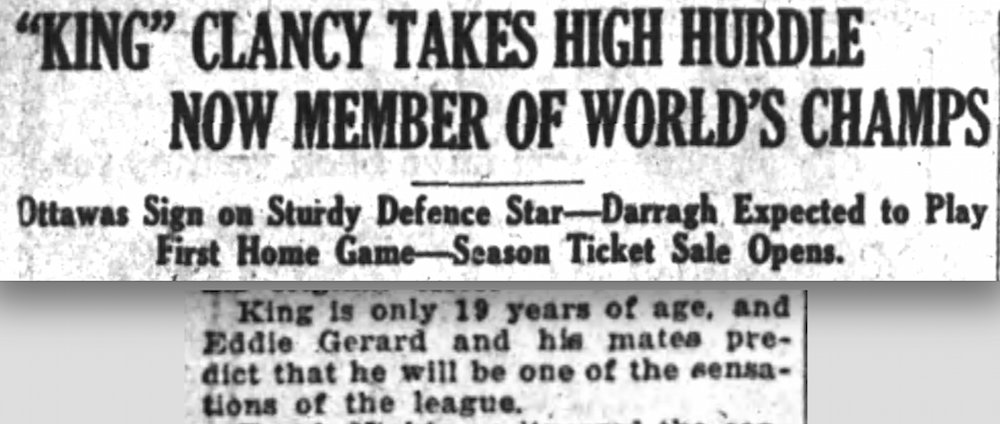

Even with Daniel’s track record, I needed more than this to go on. So, I checked the Census of Canada records. In 1911, Francis Clancy (he inherited his famous nickname from his father, Thomas, who was a rugby star known as “The King of the Heelers,” but he wasn’t born King Clancy!) appears to have had 1902 written overtop of 1901 (yes, it looks a lot like 1907!) and had his age of 10 crossed out and changed to a 9. In 1921, where no birth years are recorded, he’s listed as being 19 years old.

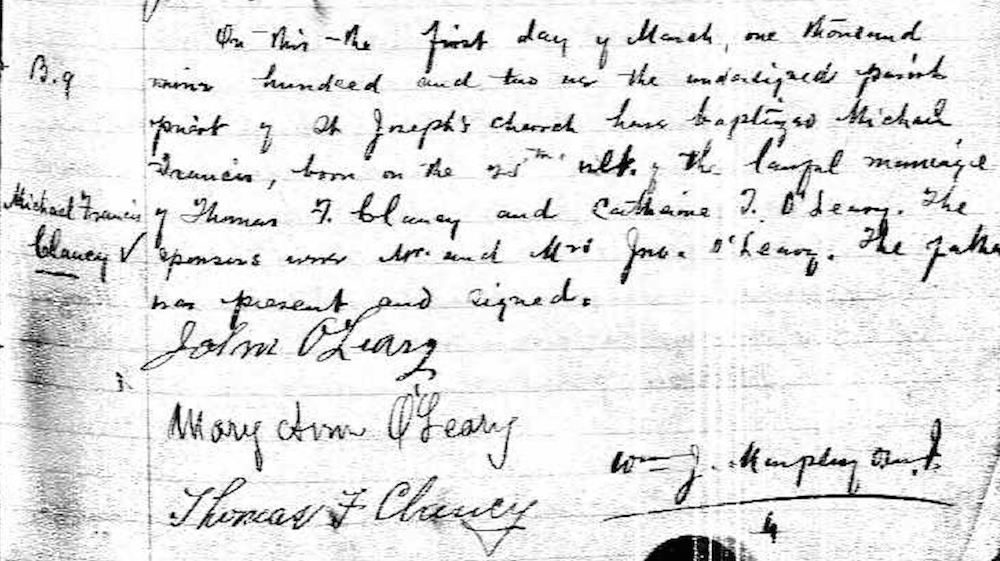

These were two more bits of evidence for a birth year of 1902 … but I know from past experience that Census information from these days can’t always be trusted. What is much more reliable, however is the statement of baptism. Clancy’s is hard to read, but it says: “On this the first day of March one thousand nine hundred and two we the undersigned parish priests of St. Joseph’s Church have baptized Michael Francis, born on the 25th inst. of the legal marriage of Thomas F. Clancy and Catherine J. O’Leary…”

Bingo!

But maybe not. Clancy’s name is supposed to be Francis Michael, not Michael Francis. Still, with everything else a perfect match, it must be him, right? Fortunately, as it turns out, Clancy’s wedding record from 1933 also lists his name as Michael Francis (and shows his age as 31, which would again indicate a birth year of 1902).

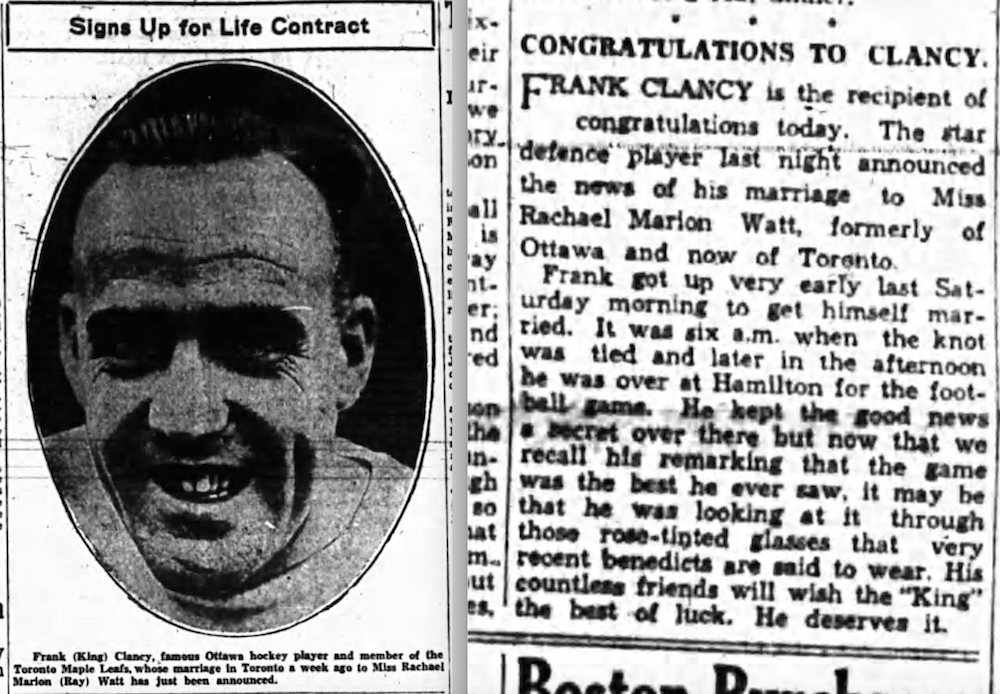

And to erase any lingering doubt about that record possibly being the wrong Clancy, newspaper coverage in both Toronto and Ottawa shortly after the wedding match the names and dates too perfectly for this to be anyone else.

Ottawa Journal, October 14, 1933.

Yet the hockey records showing his birth year as 1903 are so prevalent that you will find plenty of stories today claiming that Clancy was 18 years old in 1921 when he broke into the NHL (reputedly as the first teenager in league history – I haven’t looked into that!). But in his hometown of Ottawa at the time, people knew better. The Ottawa Journal in reporting on his signing on December 15, 1921, noted that Clancy was 19:

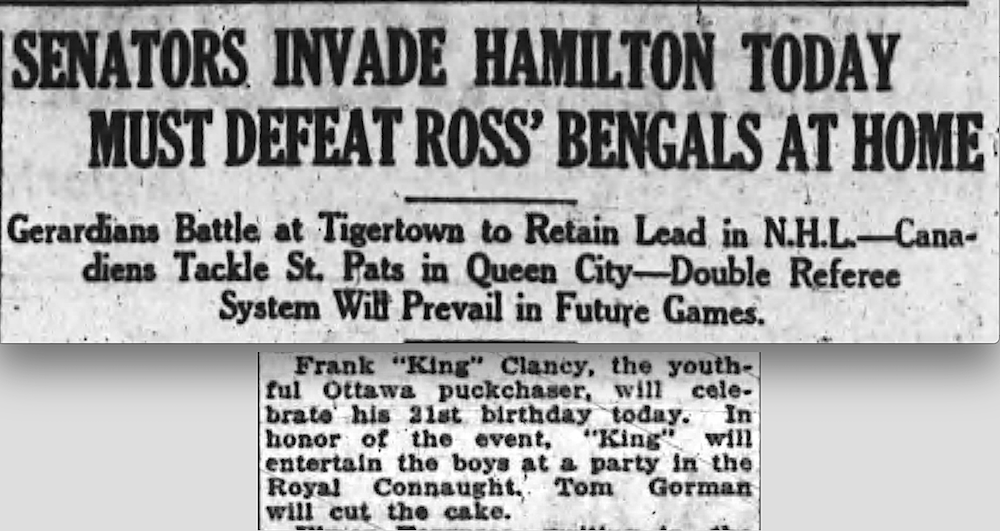

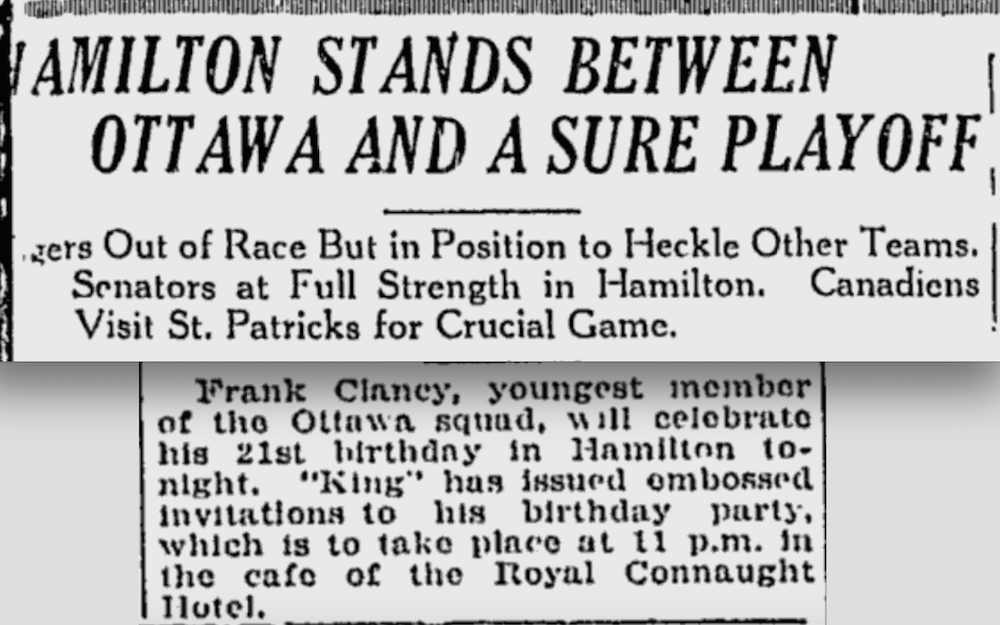

And two years later, on February 24, 1923, there was this story in the Journal noting his 21st birthday:

As well as this one that same day in the Ottawa Citizen:

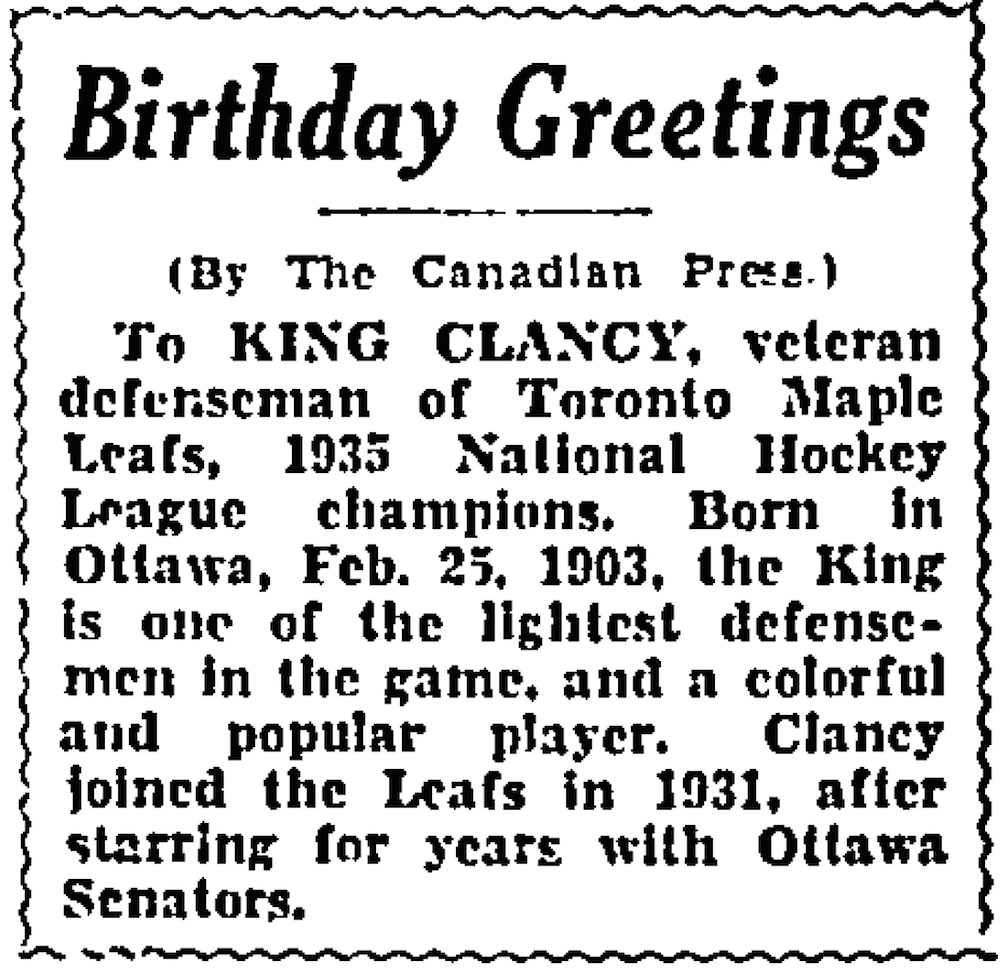

All this evidence has pretty much convinced me that Clancy really was born in 1902, but then, clearly, some time after he got to Toronto, Clancy lost a year, as this short item in The Globe notes on February 25, 1936:

So, I began to wonder two things. First, when did the NHL start to “officially” record birth dates? I sent an email to Benny Ercolani, who’s been with the NHL since 1976 and its head statistician since the 1980s. He didn’t know the answer. Neither has anyone else I’ve spoken to.

It seems reasonable to me that recording birth dates may have begun in 1932 when Jim Hendy published his first NHL Guide, which was the forerunner of the publication I’ve been working on with Dan Diamond and Associates since 1996. Hendy was publishing newspaper stories that included player birth dates at least as early as 1931 … but I’ve never seen a copy of his 1932-33 Guide. The earliest edition in the archives at the Hockey Hall of Fame is from 1936-37 … and Phil Pritchard informs me that Clancy is listed in that one as being born in 1903. (No surprise there!)

Did Hendy solicit birth dates from players? And if he did, did Clancy decide around 1932 that he’d be better off as an aging NHLer who was 29-years-old rather than 30? Maybe. But that’s nothing more than a guess.

To see if the Clancy family could shed any light on this, I contacted his son, Terry Clancy. When I asked Terry what he knew about his father’s age, he told me: “I know that he was 83 when he died (in 1986).” I told him that he may actually have been a year older than that, and then I asked him the second thing I’d been wondering about. Did he have any idea why his father filled out that form in 1972?

I wondered if Clancy had needed a passport to go to Russia for the 1972 Series in September … but Terry said his father hadn’t gone. I also wondered, with Harold Ballard soon to serve a jail sentence for fraud, if maybe Clancy was suddenly worried about his job with the Maple Leafs and decided it might be a good idea to apply for his pension.

Terry had his doubts about that … although it’s hardly the kind of thing a father would have discussed with his children. Still, he got in touch with his older sister to ask her if she’d ever heard anything. “She told me she knew something about the two [birth dates],” he wrote, “but she always went on the assumption that he was born in 1903.”

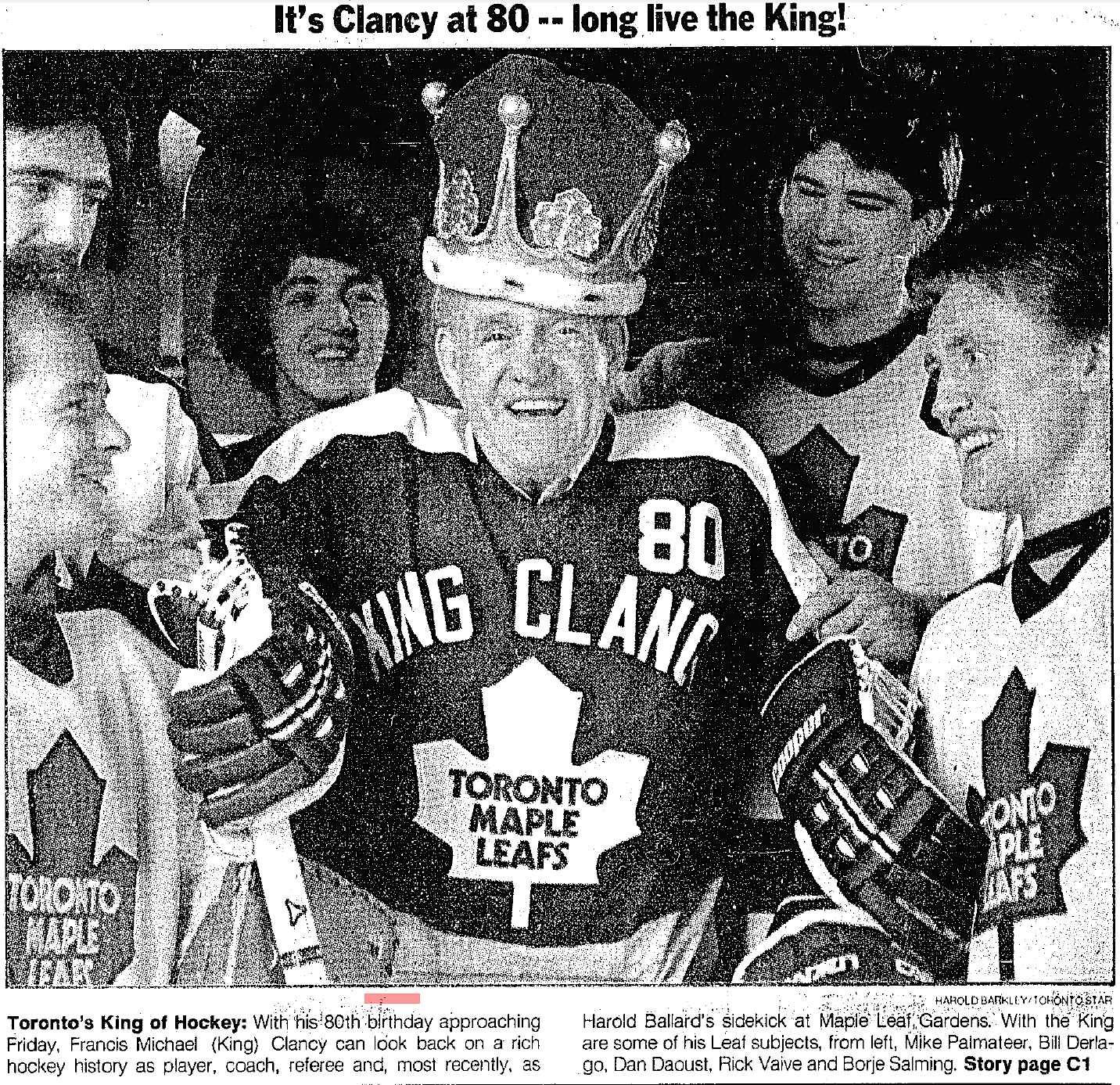

Toronto Star, February 22, 1983.

Despite having filled out that form in 1972, King Clancy certainly appears to have carried on as if he’d been born in 1903. He happily took part in 80th birthday festivities in 1983 – when he was probably turning 81.

“My father never really cared about his age,” Terry Clancy told me.

I wonder what he’d make of all this effort today!

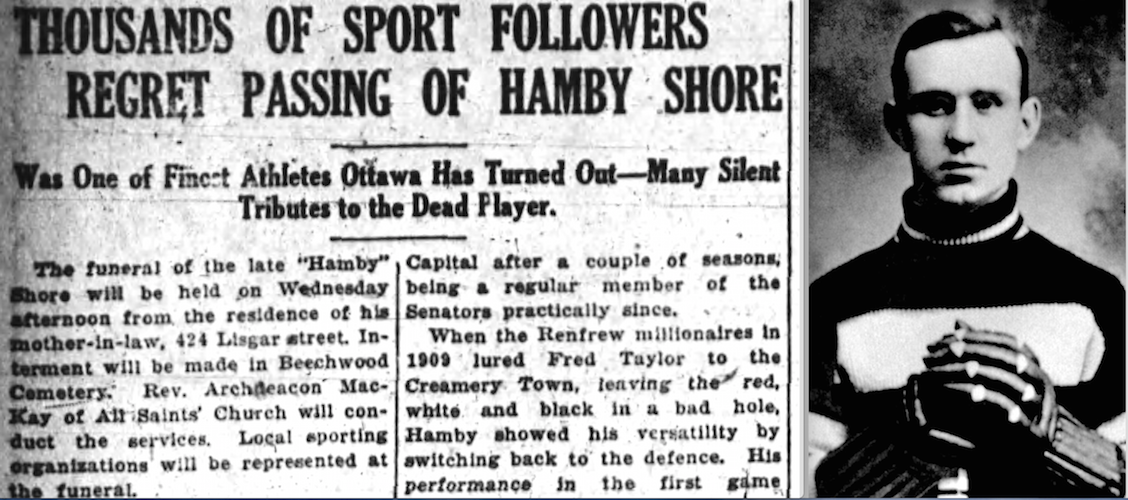

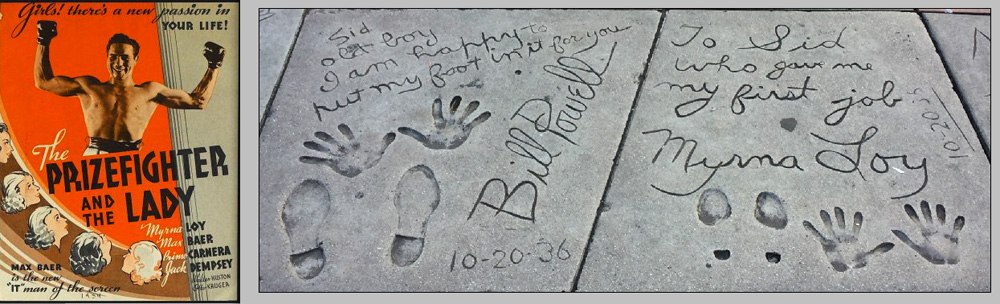

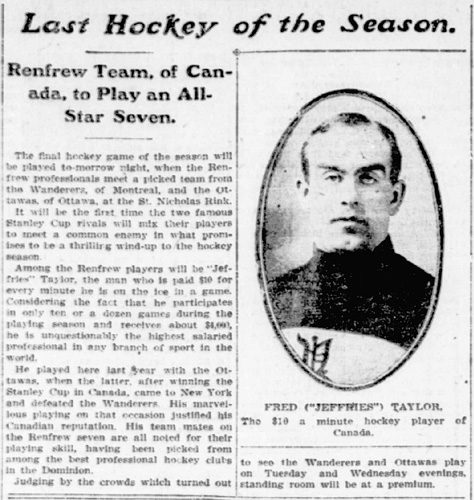

Article in The New York Daily Tribune on March 18, 1910, when Taylor

Article in The New York Daily Tribune on March 18, 1910, when Taylor

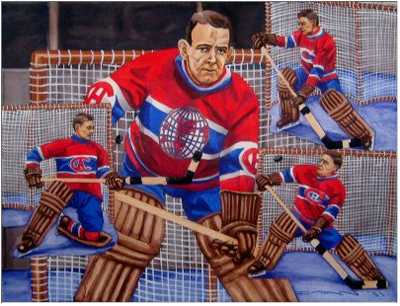

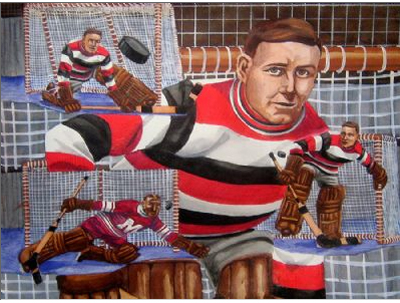

Paintings by Darrin Egan. Visit him on

Paintings by Darrin Egan. Visit him on  Contact Darrin at: inthebluepaint@gmail.com

Contact Darrin at: inthebluepaint@gmail.com

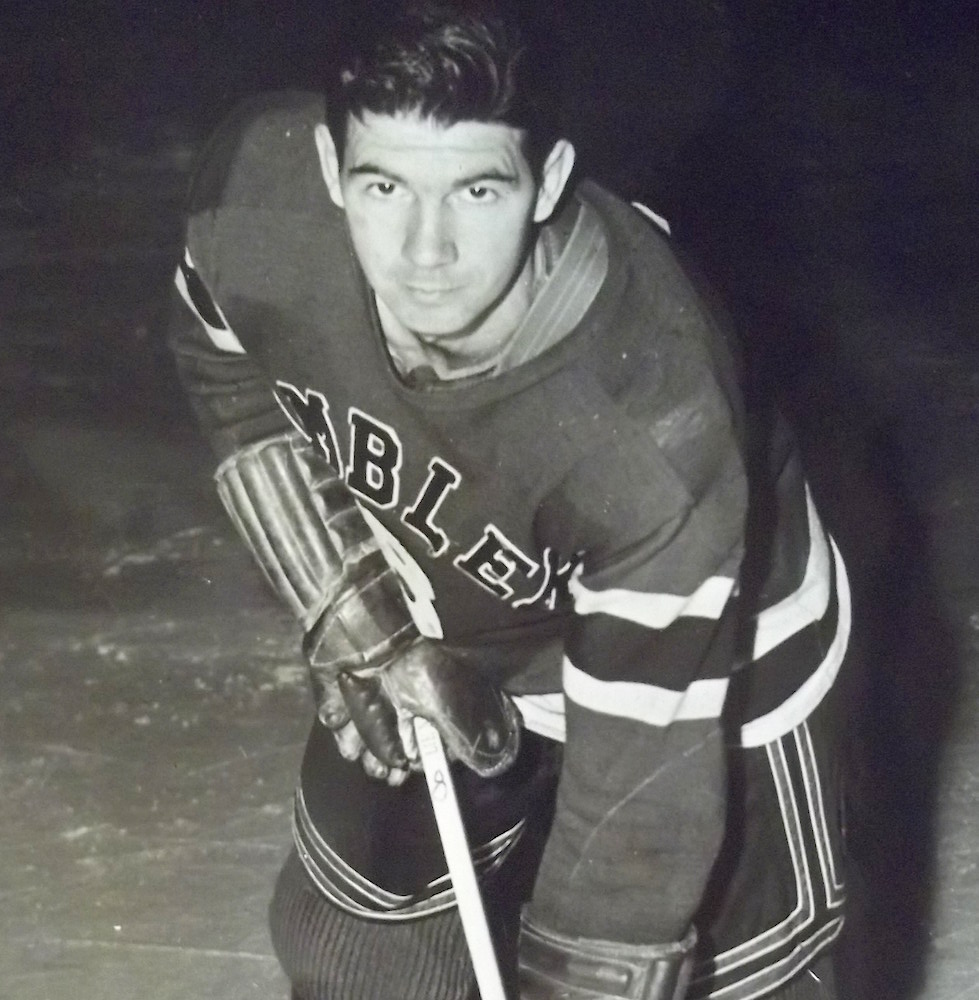

Chick Webster with the New Haven Ramblers, courtesy of Rob Webster.

Chick Webster with the New Haven Ramblers, courtesy of Rob Webster.

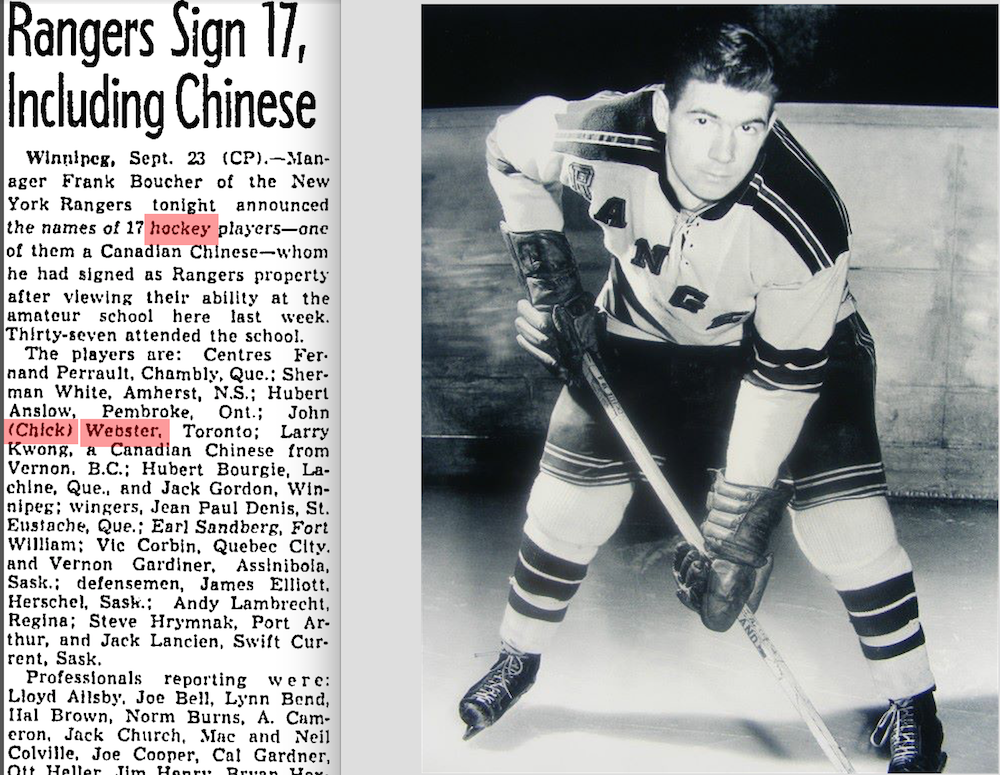

Globe and Mail, September 24, 1946. Photo courtesy of Rob Webster.

Globe and Mail, September 24, 1946. Photo courtesy of Rob Webster. Chick Webster enters the Cincinnati Mohawks dressing room and

Chick Webster enters the Cincinnati Mohawks dressing room and